1.2: The Process of Public Speaking

Tiffany Petricini

Learning Objectives

- Identify the three components of getting your message across to others

- Distinguish between the interactional models of communication and the transactional model of communication

- Analyze the evolving role of AI in interactional and transactional models of communication

- Explain the three principles discussed in the dialogical theory of public speaking

Communication is not simply about transmitting information. It is about creating shared meaning. Some call communication a science (Berger & Chaffee, 1988). Whether we are engaging one person or addressing a large group, effective communication relies on our ability to connect with others, adapt to context, and respond to feedback. Public speaking is one of the most visible ways to practice these skills, but it also serves as a window into how all communication works.

To become a strong public communicator, you must understand both the components of communication and the theories that help explain how communication functions in everyday life.

Three Core Components: Message, Skill, and Presence

Getting your message across requires more than just good ideas. It involves three essential components: the message itself, your communication skills, and your presence or sense of purpose.

- Message: The content of what you say must be clear, coherent, and meaningful. A strong message is well-organized, tailored to the audience, and supported by credible evidence. If your audience cannot follow or relate to your content, they will tune out—even if your delivery is polished.

- Skill: Communication involves both verbal and nonverbal elements. Your voice, gestures, eye contact, pacing, and use of space all contribute to how your message is received. These skills can be practiced, refined, and adapted to fit different contexts.

- Presence: Audiences respond when speakers are engaged and invested in what they are saying. Passion, curiosity, urgency, or care can help draw people in. When your message matters to you, it is more likely to matter to others.

Together, these components support not only public speaking, but everyday communication—meetings, interviews, collaborative work, and conversations that matter.

Try It: Experiment with AI-Assisted Communication

Models of Communication: From Interaction to Transaction

To understand how communication works, scholars have developed several foundational models. Two of the most influential are the interactional model and the transactional model.

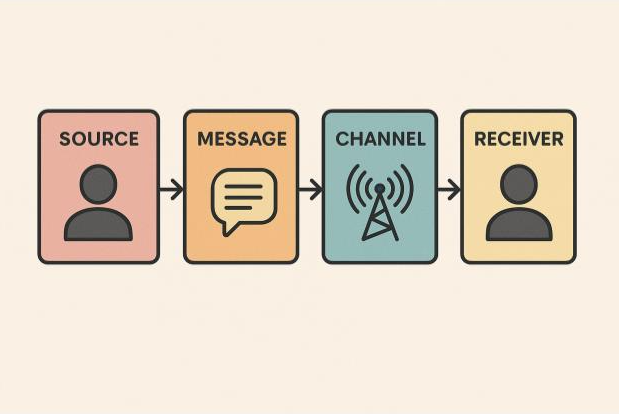

The interactional model sees communication as a one-way flow of information from sender to receiver. While this model introduces key ideas such as encoding, decoding, and feedback, it often treats communication as a series of exchanges rather than a shared experience. It is useful for thinking about basic message design, but it has limitations when applied to real-world interactions (see Shannon and Weaver, 1963; Schramm, 1954). In 1960, Berlo, using Shannon and Weaver and Schramm’s early models of communication, introduced the SMCR Model.

Figure 1.1: SMCR Model of Communication

Image Long Description

This image visually represents the Berlo’s SMCR communication model, which breaks down communication into four components:

- Source – Depicted by an icon of a person within a red box labeled “SOURCE.” This represents the originator of the communication.

- Message – Shown as a speech bubble inside an orange box labeled “MESSAGE.” This represents the content or idea being communicated.

- Channel – Represented by a broadcasting tower icon within a teal box labeled “CHANNEL.” This symbolizes the medium or method used to transmit the message.

- Receiver – Depicted by another person icon in a gray box labeled “RECEIVER,” representing the individual who receives and interprets the message.

Text Transcription

SOURCE → MESSAGE → CHANNEL → RECEIVER

Arrows connect the boxes from left to right, indicating the direction of the communication process from the source to the receiver.

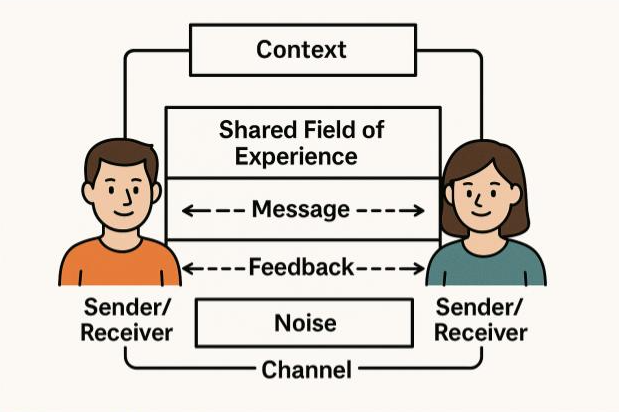

The transactional model views communication as a simultaneous, dynamic process in which all participants are both senders and receivers. Meaning is not just sent or received—it is co-created. This model emphasizes shared experience, context, and the continuous exchange of signals, including nonverbal cues, interruptions, and emotional tone (see Barnlund, 2013).

Figure 1.2: Transactional Model of Communication

Image Long Description

This image is a labeled diagram of the Transactional Model of Communication. It features two illustrated people facing each other — a male figure on the left and a female figure on the right — both labeled as Sender/Receiver. Between them is a rectangular area labeled Shared Field of Experience. Within that area:

- A double-headed arrow labeled Message runs from left to right.

- Another double-headed arrow labeled Feedback runs from right to left, just beneath the message arrow.

- Above the Shared Field of Experience is a labeled box: Context — indicating the influence of environmental or situational factors.

- Below the sender/receiver roles and message arrows, there is a box labeled Noise, which represents any interference in communication. A curved line labeled Channel connects the two Sender/Receiver roles, running through the Noise box, illustrating the medium through which the message is transmitted.

The model visually emphasizes the dynamic, simultaneous sending and receiving of messages, with feedback, context, noise, and shared experience as critical components.

Text Transcription

Context

Shared Field of Experience

<– Message –>

<– Feedback –>

Sender/Receiver Sender/Receiver

Understanding communication as transactional helps us move beyond a focus on performance. It encourages us to see communication as a collaborative act, shaped by the people involved and the environment in which it takes place.

The Role of Experience and Identity

In transactional communication, meaning depends not just on words, but on the fields of experience we bring with us—our identities, cultures, backgrounds, and beliefs. What a speaker says and what an audience hears may be different based on how each interprets those words through their own lens. This is especially important in diverse or unfamiliar audiences.

Being an effective communicator means taking those differences seriously. It involves listening with curiosity, adapting language and examples, and recognizing that communication is not neutral. It always happens within a broader context shaped by power, culture, and history.

You Try It: Practice Transactional Thinking

Dialogic Theory: Communication as Shared Meaning

Building on these ideas, the dialogic theory of public speaking argues that even public speaking should be understood as a form of dialogue—not monologue. Scholars like Ronald Arnett, Pat Arneson and Janie Harden Fritz have emphasized that communication is most ethical and effective when it involves mutual recognition and responsiveness (see Arnett & Arneson, 1999; Fritz, 2013; Fritz, Bell McManus, and Kearney, 2023).

Dialogic public speaking is grounded in three principles:

- Dialogue is more natural than monologue: Even formal speeches involve feedback. Nods, eye contact, reactions, and questions shape how speakers adjust their tone, pacing, and message.

- Meanings live in people, not words: A word may seem clear to you but carry a very different meaning for someone else. Shared meaning must be constructed, not assumed.

- Context matters: Our words take on different meanings depending on the social, cultural, and historical moment. A joke, metaphor, or reference might resonate in one setting and fall flat in another.

A dialogic approach encourages speakers to see communication not as a performance, but as a relationship. It reminds us to remain open to our audience’s responses and to approach communication as a two-way ethical act—even when the audience is not speaking aloud.

Communication in Context

Every communication event happens within a specific context. Scholars often describe this in terms of four overlapping dimensions:

- Physical context: The actual space where communication happens. Room layout, noise levels, lighting, and technology all affect how messages are delivered and received.

- Temporal context: The time of day, the sequence of events, and the moment in history shape how your message is interpreted. What follows a serious or emotional message may need to adjust its tone.

- Social-psychological context: This includes relationships, roles, and group norms. Power dynamics, expectations, and emotional climate can all influence how a message is received.

- Cultural context: Every message is shaped by cultural norms, traditions, and language patterns. Cultural awareness allows speakers to avoid misunderstandings and connect more respectfully with their audiences.

Good speakers are aware of these layers and adjust their message and delivery accordingly.

AI and the Communication Process

Artificial intelligence is transforming how we communicate. From AI-generated content to algorithmic amplification on social media, the tools we use to design and deliver messages are no longer neutral. They shape the process in subtle and profound ways.

- In interactional models, AI might serve as the tool that helps create or send a message—generating text, suggesting phrasing, or analyzing tone.

- In transactional models, AI becomes more complex. Platforms sort messages, shape responses, and influence engagement. Meaning is co-created not only with people, but with the systems that filter, track, and respond to communication.

As communicators, we must learn to reflect on how these systems operate and ask critical questions. What role does automation play in meaning-making? How does algorithmic design affect what gets heard or silenced? How can we maintain human connection and ethical responsibility in environments shaped by machines?