9.1: Determining Your Main Ideas Objectives

Tiffany Petricini

Learning Objectives

- Revisit the function of a specific purpose.

- Understand how to make the transition from a specific purpose to a series of main points.

- Be able to narrow a speech from all the possible points to the main points.

- Explain how to prepare meaningful main points.

If your speech were a meal, the body would be the main course. The body is where you dig into your core message, nourish your audience with ideas, and give them something to chew on after it’s over. It’s the heart of your message, where your credibility is built, your purpose comes alive, and your audience decides whether they’ll remember (or forget) what you said.

Figure 9.1 The Speech as a Meal

Image Long Description

This image uses a food metaphor to illustrate the structure of a speech. It shows a plate on a wooden table with a fork on the left and a knife on the right.

On the plate:

- A large grilled steak labeled “BODY” takes up the most space, symbolizing the main content of the speech.

- A serving of broccoli labeled “INTRODUCTION” is positioned to the upper left of the steak, representing the opening portion of the speech.

- A small cup of dessert labeled “CONCLUSION” is placed below the broccoli, symbolizing the closing section of the speech.

Above the plate, in bold letters, it reads: “THE SPEECH AS A MEAL”. The layout visually reinforces the idea that the body is the main course, while the introduction and conclusion are complementary elements like a side dish and dessert.

Text Transcription

Header:

THE SPEECH AS A MEAL

On Plate:

INTRODUCTION (labeled over broccoli)

BODY (labeled over steak)

CONCLUSION (labeled under dessert)

So how do you structure that main course? And more importantly, how do you make sure it lands?

Let’s start with what we know from research. Back in the mid-20th century, early communication scholars like Smith (1951), Thompson (1960), and Baker (1965) conducted studies that revealed something pretty straightforward but powerful: audiences can tell when a speech is disorganized, and they don’t like it. Disorganized speeches are harder to follow, harder to remember, and harder to trust. Organized speeches, on the other hand, are more persuasive, more credible, and more likely to stick in the minds of listeners.

That’s why structuring your speech isn’t just a technical skill. It’s a communication superpower. It helps you connect with people, earn their trust, and move them from knowing to caring to doing. In this section, we’ll walk you through how to move from your speech’s specific purpose to clear, memorable main points and how to shape those points so your message flows and your audience stays with you every step of the way.

Start with Purpose, Stay with Purpose

Before you start building the body of your speech, you need to have a clear specific purpose—a sentence that names who your audience is, what you want to accomplish, and how you’ll do it. For example:

- To inform a group of school administrators about open-source educational software.

- To persuade college students to switch from Microsoft Office to OpenOffice.

- To entertain a business group with a mock eulogy for paid software, celebrating the rise of free tools.

Even though all three examples are about open-source software, each one has a different purpose and audience—and that’s what makes each speech unique.

Once you’ve locked in your specific purpose, you can begin crafting your main points, the pillars of your message.

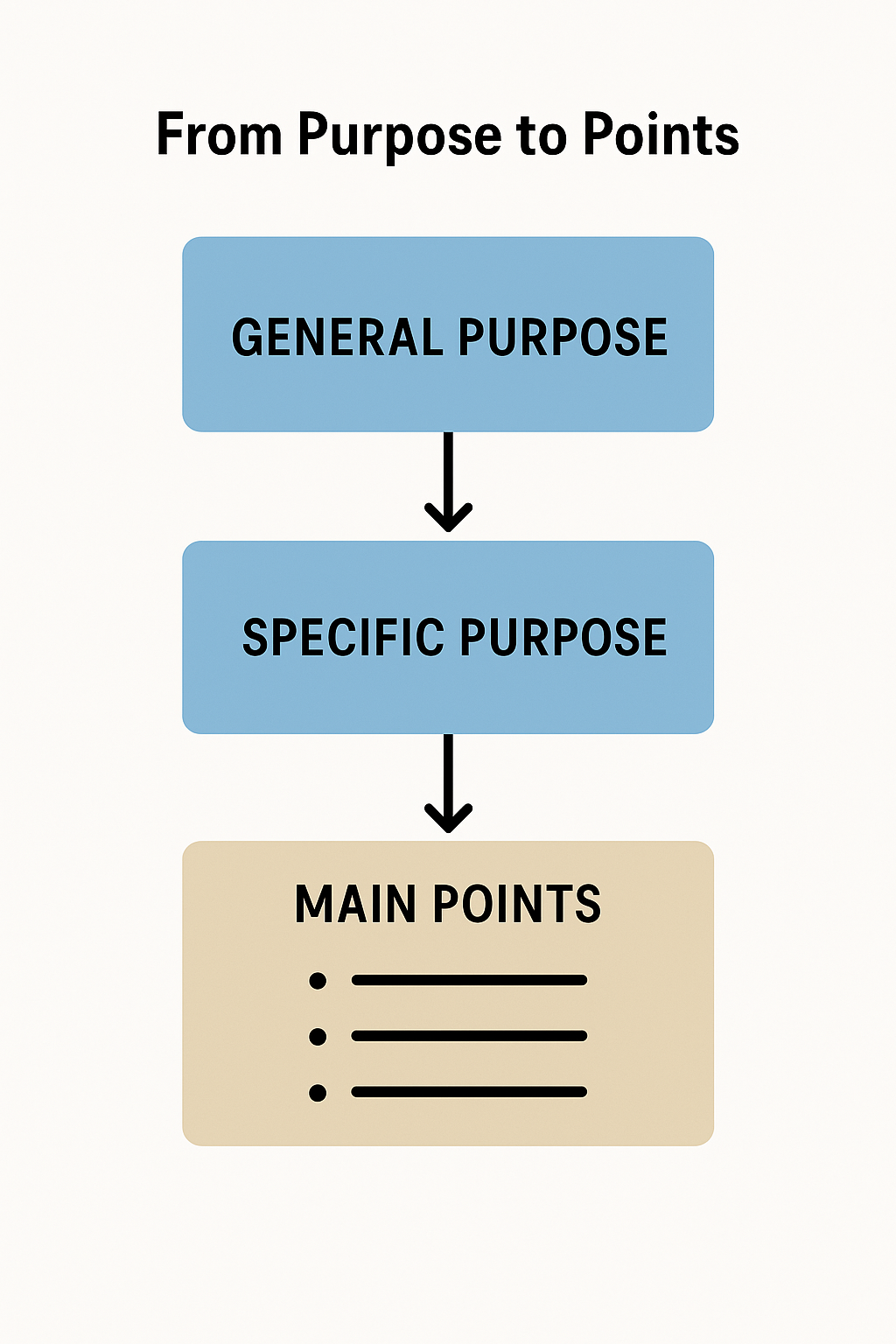

From Purpose to Points

Figure 9.2 From Purpose to Points

Image Long Description

This visual is a simple vertical flowchart with three stacked boxes and two downward-pointing arrows connecting them, illustrating the logical development of a speech.

Top Box (blue):

GENERAL PURPOSE – This represents the broad goal of the speech (e.g., to inform, persuade, or entertain).

Middle Box (blue):

SPECIFIC PURPOSE – This narrows the focus to what exactly the speaker wants the audience to understand or do.

Bottom Box (beige):

MAIN POINTS – Represented by three bullet points, this section refers to the key ideas that support the specific purpose.

Each stage flows into the next, showing a clear progression from intention to structured content.

Text Transcription

Title: From Purpose to Points

Flowchart Steps:

GENERAL PURPOSE

SPECIFIC PURPOSE

MAIN POINTS

Your main points are the core ideas that help you fulfill your purpose. They’re not just a list of things you want to say—they’re a carefully chosen set of messages that help your audience understand, remember, and care.

How Many Points?

For most student speeches, aim for 3-5 main points. Why? People can only hold so much in their short-term memory (Cowan, 2001; Miller, 1956)

More points often means less depth per point.

Clear, focused ideas are easier to support—and easier for your audience to retain.

A good rule of thumb:

- Under 3 minutes? Stick to 2 points.

- 3–10 minutes? Go with 3 points.

- Longer? You can add more but stay strategic.

How to Choose Your Points

Start by brainstorming: write down every possible idea, fact, or insight that supports your purpose. Don’t worry about organizing yet—just dump it all out.

Then chunk similar ideas together. Look for natural groupings or themes that emerge. From there, identify the essential ideas that your audience needs in order to walk away informed, persuaded, or entertained. Those become your main points.

Example:

Specific Purpose: To inform school administrators about using open-source software.

Brainstorm:

- What is open-source software?

- Why does it matter?

- Pros and cons

- History

- Examples used in schools

- Needs of the audience

- Security concerns

Chunked Main Points:

- What is open-source software?

- What are its benefits and drawbacks for schools?

- What tools should school administrators consider?

You’ve now moved from a pile of ideas to a focused structure.

![]() AI Insight

AI Insight

AI tools like ChatGPT or Gemini can help you brainstorm a list of possible points or examples. For instance, you might prompt: “List 10 main points for a 5-minute speech on [your topic].” But the real work is curating. Choose the points that align with your audience, your purpose, and your voice. Never let the tool override your intention.

Try It: Practice in Progress: From Brainstorm to Structure

Activity Introduction: Before you can deliver a well-organized speech, you have to tame the chaos of your ideas. This activity walks you through the process of turning a single purpose into a structured set of main points. You’ll move from brainstorm to clear, focused structure and see how AI can help spark ideas while you stay in control of the final design

Wrap Up: When you practice chunking your ideas into main points, you’re doing more than organizing—you’re deciding what matters most for your audience. Keep this process in mind for every speech: start broad, then narrow with intention.

5 Principles for Building Strong Main Points

1. Unity: Do They All Belong?

Every point you include should serve your specific purpose. If it doesn’t move the audience closer to that goal, leave it out, even if it’s interesting to you.

2. Separation: Are They Distinct?

Avoid overlapping ideas. Each main point should feel different from the others. If two points are too similar, combine or reframe them.

Not this:

- Apples are healthy.

- Oranges are healthy.

- Fruit is healthy.

Better:

- Fruit provides essential vitamins.

- Fruit improves digestion.

- Fruit lowers disease risk.

3. Balance: Are They Evenly Developed?

Make sure you’re not spending 4 minutes on one point and 30 seconds on another. If one point is too big, break it into two. If one is too small, either expand it or cut it.

4. Parallelism: Do They Sound Alike?

Your audience will remember your message better if your points are phrased in a similar way.

Example:

Define open-source software.

Explain how schools use software.

Describe three free software tools.

→ These vary too much in tone and structure.

Better:

Define open-source software.

Describe how it works in schools.

Recommend useful open-source tools.

→ The repetition in form supports memory.

5. Logical Flow: Do They Make Sense in Order?

Sometimes it makes sense to go chronologically, sometimes cause-to-effect, and sometimes general-to-specific. What matters most is whether your audience will be able to follow your progression without getting lost. If the order feels off, trust your gut and revise.