11.1 Why Outline?

Jonathan Woodall

Learning Objectives

- Outlines help maintain the speech’s focus on the thesis by allowing the speaker to test the scope of content, assess logical relationships between ideas, and evaluate the relevance of supporting ideas.

- Outlines help organize a message that the audience can understand by visually showing the balance and proportion of a speech.

- Outlines can help you deliver clear meanings by serving as the foundation for speaking notes you will use during your presentation.

- Use AI as a conversation partner in the process of creating an outline to test main points, organizational patterns, and clarity of ideas.

Every great speech starts with a great plan. For your speech to be as effective as possible, it needs to be organized into logical patterns. Information will need to be presented in a way your audience can understand. This is especially true if you already know a great deal about your topic. You will need to take careful steps to include pertinent information your audience might not know and to explain relationships that might not be evident to them. Using a standard outline format, you can make decisions about your main points, the specific information you will use to support those points, and the language you will use. Without an outline, your message is liable to lose logical integrity or focus. It might even deteriorate into a list of bullet points with no apparent connection to each other except the topic, leaving your audience confused about the topic and relieved when your speech is finally over.

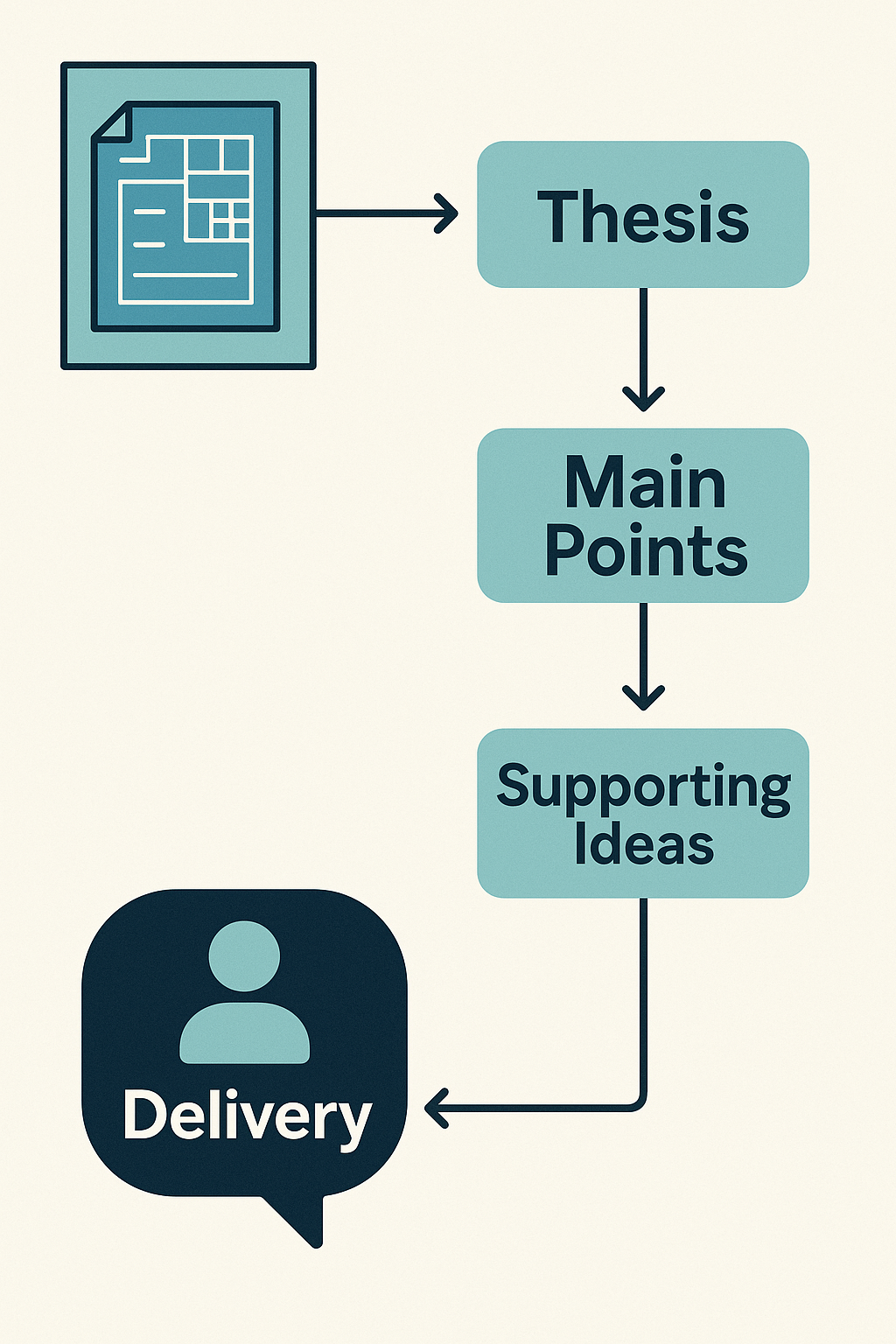

Figure 11.1 Outline Process Flowchart

Image Long Description

This image is a vertical flowchart that visually represents the logical progression of speech preparation. At the top, a document icon leads to a box labeled “Thesis.” A downward arrow connects “Thesis” to “Main Points.” Another arrow leads to “Supporting Ideas.” From “Supporting Ideas,” an arrow curves left to a speech bubble labeled “Delivery,” which contains a person icon.

The diagram illustrates that effective speech delivery depends on clearly developed ideas, built from a strong thesis supported by structured main points and supporting details.

Text Transcription

Thesis

Main Points

Supporting Ideas

Delivery

(A document icon points to “Thesis”, and a speech bubble labeled “Delivery” contains a person icon.)

Professors often teach three types of outlines, and they can be viewed as a series of stages in your speech preparation. First, a working outline is an outline you use for developing your speech. Once you are confident in the internal unity of your basic message, you can begin filling in the supporting points in descending detail—that is, from the general (main points) to the (supporting points) and then to greater detail. This second outline with everything you plan to say is called the full-sentence outline. While this outline is great for organization, it is not what you want to take to the podium with you, and so the third type of outline professors recommend is a speaking outline that condenses your full-sentence outline to aid your extemporaneous delivery. More about the types of outlines will follow this section.

Figure 11.2 Three Types of Outlines

Image Long Description

The image contains three horizontal blocks stacked vertically. Each block represents a different type of speech outline, distinguished by background color and bold, all-caps text:

- Top block (light blue) – labeled “WORKING OUTLINE”

- Middle block (light yellow) – labeled “FULL-SENTENCE OUTLINE”

- Bottom block (light green) – labeled “SPEAKING OUTLINE”

There are no icons or additional visuals; the focus is on clearly presenting the names of the outline types. The design is minimalistic and easy to read.

Text transcription

WORKING OUTLINE

FULL-SENTENCE OUTLINE

SPEAKING OUTLINE

A full-sentence outline lays a strong foundation for your message. It will call on you to have one clear and specific purpose for your message. As we have seen in other chapters of this book, writing your specific purpose in clear language serves you well. It helps you frame a clear, concrete thesis statement. It helps you exclude irrelevant information while focusing only on information that directly advances or explains your thesis. It reduces the amount of research you must do. It suggests what kind of supporting evidence is needed, so less effort is expended in trying to figure out what to do next. It helps both you and your audience remember the central message of your speech.

Finally, a solid full-sentence outline helps your audience understand your message because they will be able to follow your reasoning. Remember that live audiences for oral communications lack the ability to “rewind” your message to figure out what you said, so it is critically important to help the audience follow your reasoning instantaneously in real time.

Professors often note a reluctance among students to write full-sentence outlines. It’s a task too often perceived as busywork, unnecessary, time consuming, and restricting. On one hand, those feelings of reluctance are understandable. But on the other hand, students who carefully write a full-sentence outline show a stronger tendency to give powerful presentations of meaningful messages.

Try It! Purpose of the Outline

Activity Introduction: When giving a live speech, your audience can’t pause or replay what you’ve said, so your outline must help them follow your reasoning clearly and easily. Try this quick check to see why a full-sentence outline matters.

Wrap-Up: Strong outlines guide your audience through your ideas in real time—because unlike a video, a live speech doesn’t have a rewind button.

Tests Scope of Content

A clear, concrete thesis statement acts as a compass for your outline. Each main point should directly advance or explain your thesis. The test of the scope will be a comparison of each main point to the thesis statement. If you find a poor match, you will know you’ve wandered outside the scope of the thesis.

Let’s say the general purpose of your speech is to inform, and your broad topic area is wind-generated energy. Now you must narrow this to a specific purpose. You have many choices, but let’s say your specific purpose is to inform a group of property owners about the economics of wind farms where electrical energy is generated.

Your first main point could be that modern windmills require a very small land base, making the cost of real estate low. This is directly related to economics. Then, of course, you need to provide evidence to support your claim that only a small land base is needed.

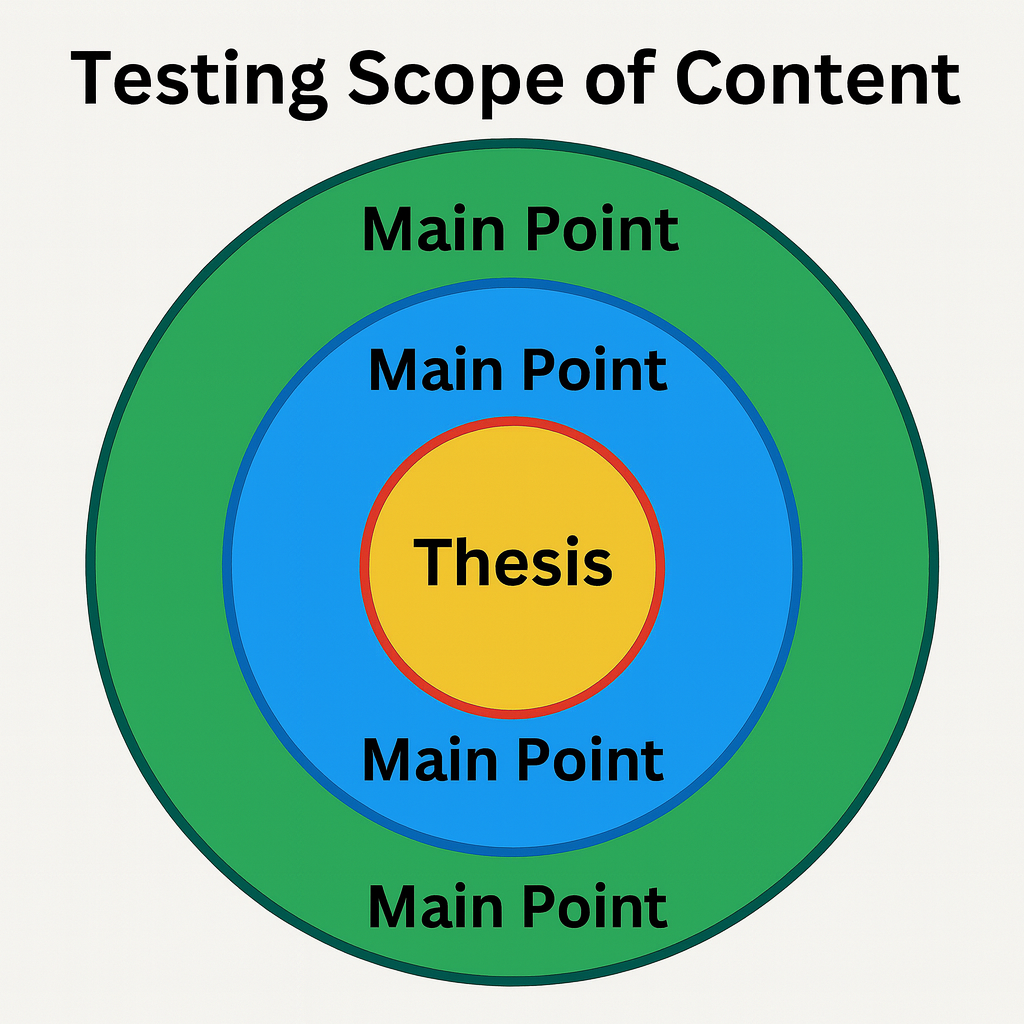

Figure 11.3 Aligning Main Points with Thesis

Image Long Description

The image features four concentric circles, with each circle representing a level of speech content:

- Innermost circle (yellow): Labeled “Thesis” – this is the core idea of the speech.

- Second circle (blue): Surrounding the thesis, labeled with “Main Point” in three separate positions.

- Third circle (green): Also labeled with “Main Point” in three positions.

At the top of the image, the heading reads “Testing Scope of Content” in bold black text.

The overall idea visually demonstrates that:

- All main points must directly relate to and support the thesis.

- Main points expand outward in scope but remain connected to the central message.

Text Transcription

Testing Scope of Content

Main Point

Main Point

Main Point

Main Point

Main Point

Thesis

In your second main point, you might be tempted to claim that windmills don’t pollute in the ways other sources do. However, you will quickly note that this claim is unrelated to the thesis since it does not address economic factors, only environmental. You must resist the temptation to add a main point that sounds good but does not fit your purpose and thesis. Perhaps in another speech, your thesis will address environmental impact, but in this speech, you must stay within the economic scope. Perhaps you will say that once windmills are in place, they require virtually no maintenance. This claim is related to the thesis. Now all you need is supporting information to support this second claim.

Your third point, which audience members will certainly want to hear, is the cost of generating electrical energy with windmills compared with other sources. This is clearly within the scope of energy economics. You should have no difficulty finding authoritative sources of information to support that claim.

AI as a Conversation Partner

One way to test the scope and focus of your main points is to use Artificial Intelligence (AI) as a conversation partner during your outline creative process. Just like a student might run an idea by a friend, or professor after class, AI can be accessed as a great tool during the establishment of an outline, so in this chapter we will explore different ways to use AI and provide some safeguards to make sure AI is a collaborative partner in YOUR creative process, and not a cheap substitute for substantive work on your part.

For example, to check the relationship between your main points and the thesis you have chosen, you can go to Microsoft Copilot and type in a prompt. We will use the example of wind-generated energy above to check the three main points already established. The prompt was entered as follows:

“I am outlining a speech that seeks to inform a group of property owners about the economics of wind farms where electrical energy is generated. I have come up with three main points. First, modern windmills require a very small land base. Second, once windmills are in place, they require virtually no maintenance. Last, the cost for generating electrical energy with windmills is lower compared to other sources. Do these points advance my thesis in a way that the audience can understand and how might I make them better?”

The response received from Copilot AI was this:

“Modern Windmills Require a Very Small Land Base”

Why it works: This addresses a common concern among property owners—land use.

How to improve:

- Clarify the benefit: Emphasize that the land around wind turbines can still be used for farming or grazing, which means dual land use.

- Use a comparison: For example, “A single wind turbine only takes up about a quarter-acre of land—less than the size of a tennis court.”

Revised point: “Wind turbines use minimal land and allow for continued agricultural use, maximizing land value.”

“Once Windmills Are in Place, They Require Virtually No Maintenance”

Why it works: It suggests low ongoing cost, which is attractive economically.

How to improve:

- Be more precise: “Virtually no maintenance” might sound too good to be true. Instead, say they require low maintenance and explain what that means (e.g., periodic inspections, remote monitoring).

- Add a stat: Mention average annual maintenance costs per turbine if available.

Revised point: “Wind turbines have low maintenance needs, with most systems monitored remotely and requiring only occasional servicing.”

“The Cost for Generating Electrical Energy with Windmills Is Lower Compared with Other Sources”

Why it works: This is the core economic argument.

How to improve:

- Be specific: Mention the cost per kilowatt-hour (kWh) compared to fossil fuels or nuclear plants.

- Highlight long-term savings: Emphasize that wind energy has no fuel costs and stable pricing over time.

Revised point: “Wind energy is among the cheapest sources of electricity today, offering long-term savings and price stability.”

In asking this one question, you can see the different aspects of each main point that now can be thought through and planned efficiently. The conversation can continue, or you can take these suggestions and tighten the focus of the speech. Additionally, please note that AI can help you in your research by suggesting some material you need to uncover to be informative to your audience. This should help you in the outline process. However, do not simply take AI’s word on the accuracy of any evidence or statistics. Always verify and corroborate facts with other, independent sources, because ultimately, you are the one responsible for the credibility of the information you share.

Try It! AI Check: Do My Main Points Support My Thesis?

Activity Introduction: Even well-written speeches can wander off track if main points don’t clearly connect to the thesis. This activity will help you check your focus and practice using AI as a conversation partner in your outlining process.

Wrap up: AI can be a great conversation partner for testing your outline’s focus, but remember, you are the final editor of your message. Use its feedback to sharpen your reasoning, not replace your judgment.

Tests Logical Relation of Parts

You have many choices for your topic, and therefore, there are many ways your content can be logically organized. In the example above, we simply listed three main points that were important economic considerations about wind farms. Often the main points of a speech can be arranged into a logical pattern; let’s take a look at some such patterns.

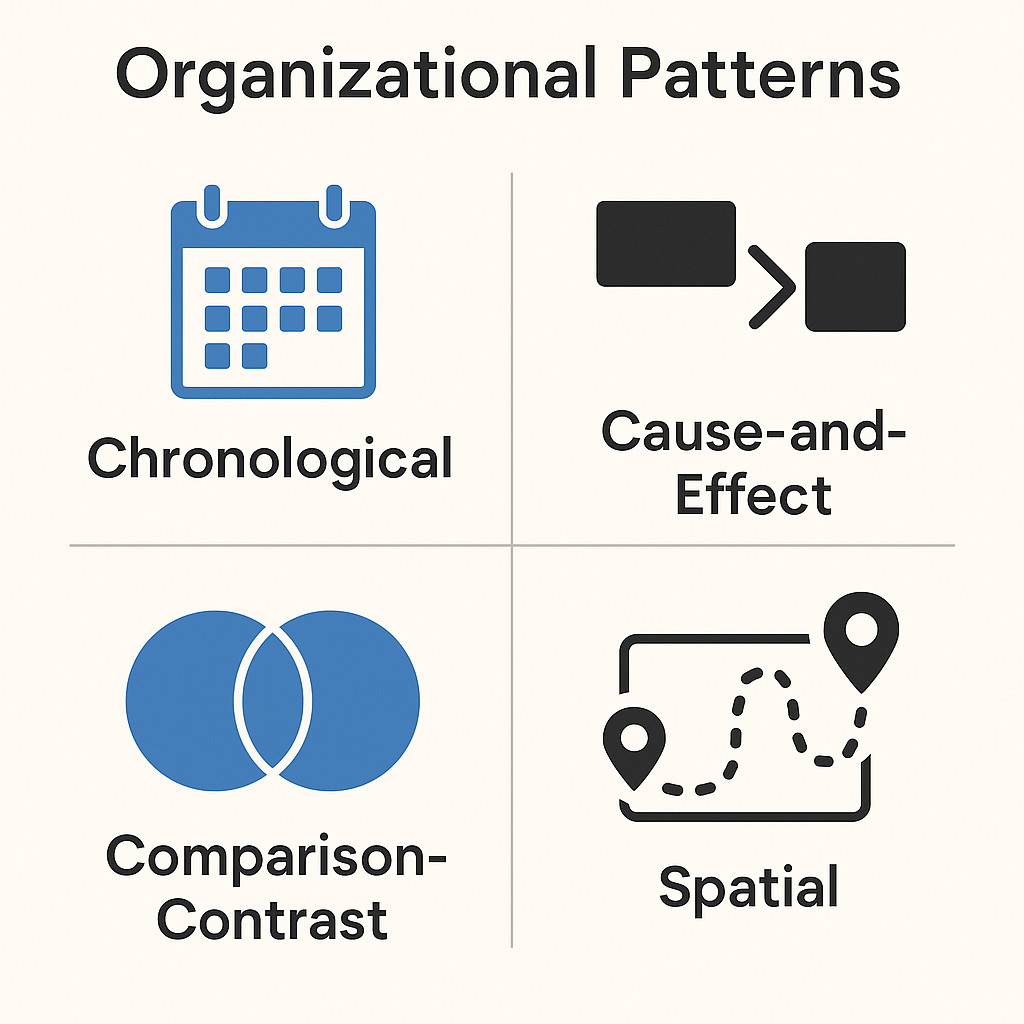

Figure 11.4 Several Types of Organizational

Image Long Description

The image is divided into four quadrants, each representing a different organizational pattern used in speech structure:

- Top Left (Chronological)

- Icon: A calendar with squares representing dates.

- Text: “Chronological”

- This pattern organizes content in time order — past to present or step-by-step.

- Top Right (Cause-and-Effect)

- Icon: Two black rectangles connected by an arrow indicating direction.

- Text: “Cause-and-Effect”

- This structure shows how one event leads to another — causes leading to results.

- Bottom Left (Comparison-Contrast)

- Icon: Two overlapping circles (like a Venn diagram).

- Text: “Comparison-Contrast”

- This pattern highlights similarities and differences between two or more topics.

- Bottom Right (Spatial)

- Icon: A path connecting two location pins with a dashed route.

- Text: “Spatial”

- This organization arranges ideas based on physical or directional space.

Text Transcription

Organizational Patterns

Chronological

Cause-and-Effect

Comparison-Contrast

Spatial

A chronological pattern arranges main ideas in the order events occur. In some instances, reverse order might make sense. For instance, if your topic is archaeology, you might use reverse order, describing the newest artifacts first. A biographical pattern is usually chronological. In describing the events of an individual’s life, you will want to choose the three most significant events. Otherwise, the speech will end up as a very lengthy and often pointless timeline or bullet point list. For example, Mark Twain had several clear phases in his life. They include his life as a Mississippi riverboat captain, his success as a world-renowned writer and speaker, and his family life. A simple timeline would present great difficulty in highlighting the relationships between important events. An outline, however, would help you emphasize the key events that contributed to Mark Twain’s extraordinary life.

A cause-and-effect pattern calls on you to describe a specific situation and explain what the effect is. However, most effects have more than one cause. Even dental cavities have multiple causes: genetics, poor nutrition, teeth too tightly spaced, sugar, ineffective brushing, and so on. If you choose a cause-and-effect pattern, make sure you have enough reliable support to do the topic justice.

Although a comparison-contrast pattern appears to dictate just two main points, McCroskey et al. (2003), explain how a comparison-and-contrast can be structured as a speech with three main points. They say that “you can easily create a third point by giving basic information about what is being compared and what is being contrasted. For example, if you are giving a speech about two different medications, you could start by discussing what the medications’ basic purposes are. Then you could talk about the similarities, and then the differences, between the two medications” (McCroskey et al., 2003).

Tests Organizational Patterns with AI

If you are unsure which organizational pattern would be best to use, then ask AI to show you the differences between the different patterns. For example, let’s take the example above and ask CoPilot “How would these three main points fit into a chronological pattern?”

The answer was to place the main points in this order:

- Land Use: The Starting Point – “Modern windmills require a very small land base.”

- Installation and Maintenance: What Happens After Setup – “Once windmills are in place, they require virtually no maintenance.”

- Energy Production and Cost Savings: The Long-Term Benefit – “The cost for generating electrical energy with windmills is lower compared with other sources.”

Let’s ask the same question, but change the organization pattern to another option, “How would these three main points fit into a comparison-contrast pattern?”

- Land Use: Wind vs. Other Energy Sources – “Modern windmills require a very small land base.”

- Maintenance: Wind vs. Traditional Power Plants – “Windmills require low maintenance once installed.”

- Cost of Energy: Wind vs. Other Sources – “Wind energy is cheaper to generate than many other sources.”

While the points are in the same order as the first example, they would be substantiated in two different ways, resulting in two very different speeches. It’s up to you, as the speaker, to determine which pattern more effectively achieves your objective. Let’s ask the question one more time with a different organizational pattern: “How would these three main points fit into a spatial pattern?”

For this prompt, before CoPilot gave me the material for the outline, it replied with a warning, “A spatial pattern organizes information based on physical location or layout. For your speech on wind farm economics this pattern may not be the best, this pattern works well if you want to guide your audience through the physical space of a wind farm—from the land it occupies, to the structure and upkeep of the turbines, to the broader energy grid where the electricity is delivered and used.”

Whatever logical pattern you use (full list is given in Chapter 10), if you examine your thesis statement and then look at the three main points in your outline, you should easily be able to see the logical way in which they relate. Choosing an organizational pattern is a rhetorical choice that you make as a speaker, and the goal in this selection is choosing a pattern that most effectively and clearly communicates your thesis to your audience.

Try It! Identify the Organizational Patterns

Activity Introduction: A well-organized outline helps your audience follow your reasoning in real time. In this activity, you’ll match each speech example to the organizational pattern it follows, just as an AI tool might classify patterns to test the flow of ideas.

Wrap-Up: Recognizing patterns helps you check whether your speech flows logically. When you ask AI to analyze your outline, it can identify these same structures which helps you see if your organization supports your purpose and audience understanding.

Tests Relevance of Supporting Ideas

When you create an outline, you can clearly see that you need supporting evidence for each of your main points. For instance, using the example above about wind-generated energy, your first main point claims that less land is needed for windmills than for other utilities. Your supporting evidence should be about the amount of acreage required for a windmill and the amount of acreage required for other energy generation sites, such as nuclear power plants or hydroelectric generators. Your sources should come from experts in economics, economic development, or engineering. The evidence could consist of expert opinion but not the opinions of ordinary people. The expert opinion will provide stronger support for your point.

Similarly, your second point claims that once a wind turbine is in place, there is virtually no maintenance cost. Your supporting evidence should show a contrast in the cost of annual maintenance for windmills with the cost of annual maintenance for other forms of energy. If you used a comparison with nuclear plants to support your first main point, you should do so again for the sake of consistency. It becomes very clear, then, that the third main point about the amount of electricity and its profitability needs authoritative references to compare it to the profit from energy generated at a nuclear power plant. In this third main point, you should make use of just a few well-selected statistics from authoritative sources to show the effectiveness of wind farms compared to the other energy sources you’ve cited.

Where do you find the kind of information you would need to support these main points? A reference librarian can quickly guide you to authoritative statistics manuals and help you make use of them.

An important step you should take note of is that the full-sentence outline includes its authoritative sources within the text. This is a major departure from the way you have learned to write a research paper. In the research paper, you can add that information to the end of a sentence, leaving the reader to turn to the last page for a fuller citation. In a speech, however, your listeners can’t do that. From the beginning of the supporting point, you need to fully cite your source so your audience can immediately assess its importance.

Because this is such a profound change from the academic habits that you’re probably used to, you will have to make a concerted effort to overcome the habits of the past and provide the information your listeners need when they need it.

Test the Balance and Proportion of the Speech

Part of the value of writing a full-sentence outline is the visual space you use for each of your main points. Is each main point of approximately the same importance? Does each main point have the same number of supporting points? If you find that one of your main points has eight supporting points while the others only have three each, you have two choices: either choose the best three from the eight supporting points or strengthen the authoritative support for your other two main points.

Remember that you should use the best supporting evidence you can find even if it means investing more time in your search for knowledge.

Try It! Balance and Proportion Reflection

Wrap-Up: Balance in an outline mirrors balance in delivery. Equal development of main points builds credibility and rhythm for your audience.

Serves as Notes during the Speech

Although we recommend writing a full-sentence outline during the speech preparation phase, you should also create a shortened outline that you can use as notes allowing for a strong delivery. This is known as a keyword or delivery outline. If you were to use the full-sentence outline when delivering your speech, you would do a great deal of reading, which would limit your ability to make eye contact and use gestures, hurting your connection with your audience. For this reason, we recommend writing a short-phrase outline that can be used when you speak. Some speakers transfer this outline onto notecards or create “card-like” slides that can be read on a device in front of the audience. Whichever method you choose to use, it should allow you to feel comfortable and confident while making a connection with your audience.

What follows is a suggested breakdown of slides or cards, if you choose (or your professor chooses a method for you) to move from the keyword outline to notecards or prompt slides on your personal device. Remember that application like Microsoft PowerPoint and Google Slides have a “notes” section that can be displayed when the visual aid is in “presentation mode.” Using a computer application with which you are familiar might be as effective as the once well-regarded notecard method, but the breakdown of information included in each section will most likely be the same. Your first slide/card can contain your thesis statement and other key words and phrases that will help you present your introduction. Your second slide/card can contain your first main point, together with key words and phrases to act as a map to follow as you present. If your first main point has an exact quotation you plan to present, you can include that on your slide/card. Your third slide/card should be related to your second main point, your fourth slide/card should be about your third main point, and your fifth slide/card should be related to your conclusion. In this way, your five slides/cards follow the very same organizational pattern as your full outline. In the next section, we will explore more fully how to create a speaking outline.