11.3 Using Outlining for Success

Jonathan Woodall

Learning Objectives

- Understand five basic principles of outline creation.

- Use AI as a conversation partner in the process of evaluating an outline that advances the thesis and adheres to the five basic principles.

As with any part of the speech process, there are some pretty commonly agreed upon principles for creating an outline. Now that we’ve examined the basics of outline creation, there are some important factors to consider when creating a logical and coherent outline: singularity, consistency, adequacy, balance, and parallelism. Remember that you can copy your outline into the prompt area of an AI tool and ask for an evaluation of these principles of a great outline.

Singularity

For the sake of clarity, make sure your thesis statement expresses one idea only. Only in this way will it be optimally useful to you as you build your outline. If you have narrowed your topic skillfully, you can readily focus the thesis statement as one central point. For instance, if you have a thesis statement that says the Second Amendment protects gun ownership rights, but most people are unaware of the responsibility involved, you have a thesis statement focusing on two different issues. Which focus will you follow? It’s crucial to choose just one, saving the other perhaps for a different speech.

The same holds true for your three main points: they should each express one clear idea. For the sake of your audience, maintain clarity. If many different ideas are required in order to build a complete message, you can handle them in separate sentences with the use of such transitions as “at the same time,” “alternately,” “in response to that event,” or some other transition that clarifies the relationship between two separate ideas.

Consistency

The entire point of framing a thesis with one clear focus is to help you maintain consistency throughout your speech. Beyond the grammatical requirements of subject-verb agreement, you will want to maintain a consistent approach. For instance, unless your speech has a chronological structure that begins in the past and ends in the future, you should choose a tense, past or present, to use throughout the speech. If you want to use second person to directly address your audience by using you, as this textbook does, then you should maintain that voice throughout and make sure you don’t switch to third person. Similarly, you should choose language and use it consistently. For instance, use humanity instead of mankind or humans, and use that term throughout.

Similarly, define your terms and use those terms only to designate the meanings in your definition. To do otherwise could result in equivocation and confusion. For instance, if you use the word “right” in two or three different senses, you should change your language. The word “right” can be applicable to your right to a good education; the ethical difference between right and wrong; and the status of a statement as right, or accurate and correct. By the same token, in a health care setting, saying that a medical test had a positive outcome can be confusing. Does the patient test positive for the presence of disease, or does the test reveal some good news? If you find yourself using the same word to mean different things, you will need to spend extra time in your speech explaining these meanings very clearly—or avoid the problem by making other word choices.

Adequacy

To make sure your audience understands your speech, you must set aside the assumption that what is obvious to you is also obvious to your audience. Therefore, pay attention to adequacy in two ways: definitions of terms and support for your main points.

You should use concrete language as much as you can. For instance, if you use the word “community,” you’re using an abstract term that can mean many things. You might be referring to a suburban neighborhood; to a cultural group, such as the Jewish community; to an institutional setting that includes an academic community; or to a general sense of overarching mainstream community standards for what materials should or should not be broadcast on television, for instance. You may not find any definition of “community” that conveys your meaning. Therefore, you will need to define for your audience what you mean by “community.”

Adequacy is also a concern when you use evidence to support your main points. Evidence of the right kind and the right weight is needed. For instance, if you make a substantial claim, such as that all printed news sources will be obsolete within ten years, you need expert sources. This means you need at least two well-known experts from the institutions that provide news (newspapers, television news, or news radio). They should be credible sources, not sources with extreme views whose contact with reality is questioned. This will give you the right kind of evidence, and a large enough amount of evidence.

Balance

A full sentence outline readily shows whether you are giving “equal time” to each of your three main points. For example, are you providing three pieces of evidence to support each main point? It should also show whether each main point is directly related to the thesis statement.

Parallelism

Parallelism refers to the idea that the three main points follow the same structure or make use of the same kind of language. For instance, in the sample outline we used previously, you see that each of the main points emphasizes the topic, smart dust.

Parallelism also allows you to check for inconsistencies and self-contradictory statements. For instance, does anything within main point two contradict anything in main point one? Examining your text for this purpose can strengthen the clarity of your message. For instance, if main point one claims that computer crime leaves an electronic trail, but main point two claims that hackers often get away with their crimes, you have some explaining to do. If an electronic trail can readily lead to the discovery of the electronic felon, how or why do they get away with it? The answer might be that cybercrime does not fall within the jurisdiction of any law enforcement agency or that the law lags behind technology. Perhaps there are other reasons as well, and you must make sure you don’t leave your audience confused. If you confuse them, you will sound confused, and you will lose credibility. There is no doubt that a full-sentence outline provides the most useful opportunity to examine your message for the details that either clarify or undermine your message.

Finally, your conclusion should do two things. First, it should come “full circle” in order to show the audience that you have covered all the territory you laid out in your preview. Second, it should provide satisfying, decisive, psychological closure. In other words, your audience should know when your speech is over. You should not trail off. You should not have to say, “That’s it.” Your audience should not have to wait to see whether you’re going to say anything else. At the right time, they should feel certain that the speech is over and that they can clap.

Using AI for a Successful Outline

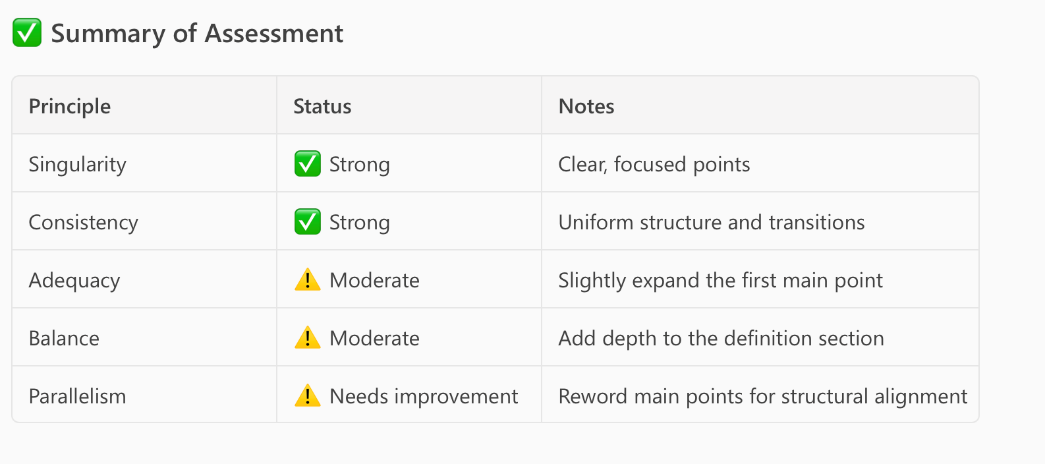

Using the full sentence outline from this chapter, we can create a prompt to ask AI to assess the outline’s singularity, consistency, adequacy, balance, and parallelism. When done for the outline provided about star dust, the response from Copilot is shared below:

Figure 11.4: Copilot Summary of Assessment

Image Long Description

This image contains a structured table with three columns: Principle, Status, and Notes, under the heading “ Summary of Assessment.” It evaluates five principles used in structuring a presentation or piece of writing. Each principle is rated as Strong, Moderate, or Needs Improvement, with specific improvement suggestions in the Notes column.

Text Transcription

Summary of Assessment

Principle | Status | Notes

Singularity | Strong | Clear, focused points

Consistency | Strong | Uniform structure and transitions

Adequacy | Moderate | Slightly expand the first main point

Balance | Moderate | Add depth to the definition section

Parallelism | Needs improvement | Reword main points for structural alignment

In addition to this very useful chart of the strengths and weaknesses of the full-sentence outline, CoPilot offered suggestions for strengthening the adequacy, balance and parallelism of the work. Regarding adequacy, AI suggested these changes, “The definition section (Main Point I) could benefit from a bit more explanation of how smart dust actually works (e.g., how it communicates, powers itself, or is deployed). A brief mention of current prototypes or limitations would also help round it out.” Depending on the audience, the suggestion given by AI might not be applicable to your situation, because defining something for a group already familiar with it could be seen as talking down to the audience or not respecting their prior knowledge, so as we have stated before, you as the speaker has the ultimate responsibility to communicate clearly and effectively to the audience. Regarding balance, Ai reported, “Consider expanding the first section slightly to match the depth of the others—perhaps by including a brief timeline of development or mentioning current research institutions working on smart dust.” Note that AI points us to the place that needs work and offers some suggestions of how to make it stronger. This can be followed by more conversations with CoPilot AI. Lastly, regarding parallelism, Copilot offered the following assessment: “Your main points are not fully parallel: 1. Smart dust is an assembly of microcomputers (definition) – 2. Smart dust could be an enormous asset in covert military operations (application) – 3. Smart dust could also have applications to daily life (application).” The suggestion provided to fix the unparallel main points is to reword the first point to match the structure of the others, so main point 1 would read, “Smart dust could revolutionize computing through micro-scale technology” or “Smart dust could serve as a foundational technology for future applications.” AI suggests options, but it is up to you as the speaker to choose the right one for this speech.