13.1: Techniques and Methods of Speech Delivery

Rosemary Martinelli

Learning Objectives

- Differentiate among the four methods of speech delivery

- Understand when to use each of the four methods of speech delivery

The easiest approach to speech delivery is not always the best. Substantial work goes into the careful preparation of an interesting and ethical message, so it is understandable that you may have the impulse to avoid “messing it up” by simply reading it word for word. But if you do this you miss out on one of the major reasons for studying public speaking and presentation: to learn ways to “connect” with your audience and to increase your confidence in doing so. You already know how to read, and you already know how to talk. But public speaking and presenting is neither reading nor talking. In the end, it is about having a conversation with an audience, individual person or group. But with that conversation comes a formality and preparation that distinguishes it from other modes of communication and from simple conversation. And now that we have more virtual presentations via ZOOM or other technology, the preparation and practice that goes with public speaking takes on a greater importance in how we connect “across the miles” and “across the computer screens.”

Speaking in public has more formality than talking. During a speech, you present yourself professionally. This doesn’t mean you must always wear a suit or “dress up” (unless your instructor asks you to or the person inviting you to give the presentation indicates that there is a professional attire required for the event), but it does mean making yourself presentable by being well-groomed and wearing clean, appropriate clothes. It also means being prepared to use language correctly and appropriately for the audience and the topic, to make eye contact with your audience, to include non-verbals correctly, and to know your topic well. You will recall from an earlier chapter that these elements form what is often called the “ethos”—the spirit that gives the speaker—that’s you—credibility!

In other words, your presentation must be researched, planned and practiced, thereby enhancing your credibility and reinforcing your expertise on the topic on which you are presenting.

Speaking professionally allows for meaningful pauses, eye contact with the audience no matter the size of the group, small changes in word order, and vocal emphasis. Reading is a more or less exact replication of words on paper without the use of any nonverbal interpretation. Speaking, as you will realize if you think about excellent speakers you have seen and heard, provides a more animated and enthusiastic message. This enthusiasm and what some people call “passion” in a presentation should be noticeable no matter the seriousness of the content. You must be able to share with the audience that what you are about to present is what you truly believe in: your knowledge of the topic, your ability to inform and to persuade, and, in some cases, your ability to motivate the audience to take action on whatever information you are sharing.

All of this sound complicated? Actually, it is not. First, let’s distill all forms of presentations into just four (4) methods or modes of delivery that can help you balance between too much and too little formality and detail when giving a public speech or presentation: they are called impromptu, manuscript, memorization, and extemporaneous delivery.

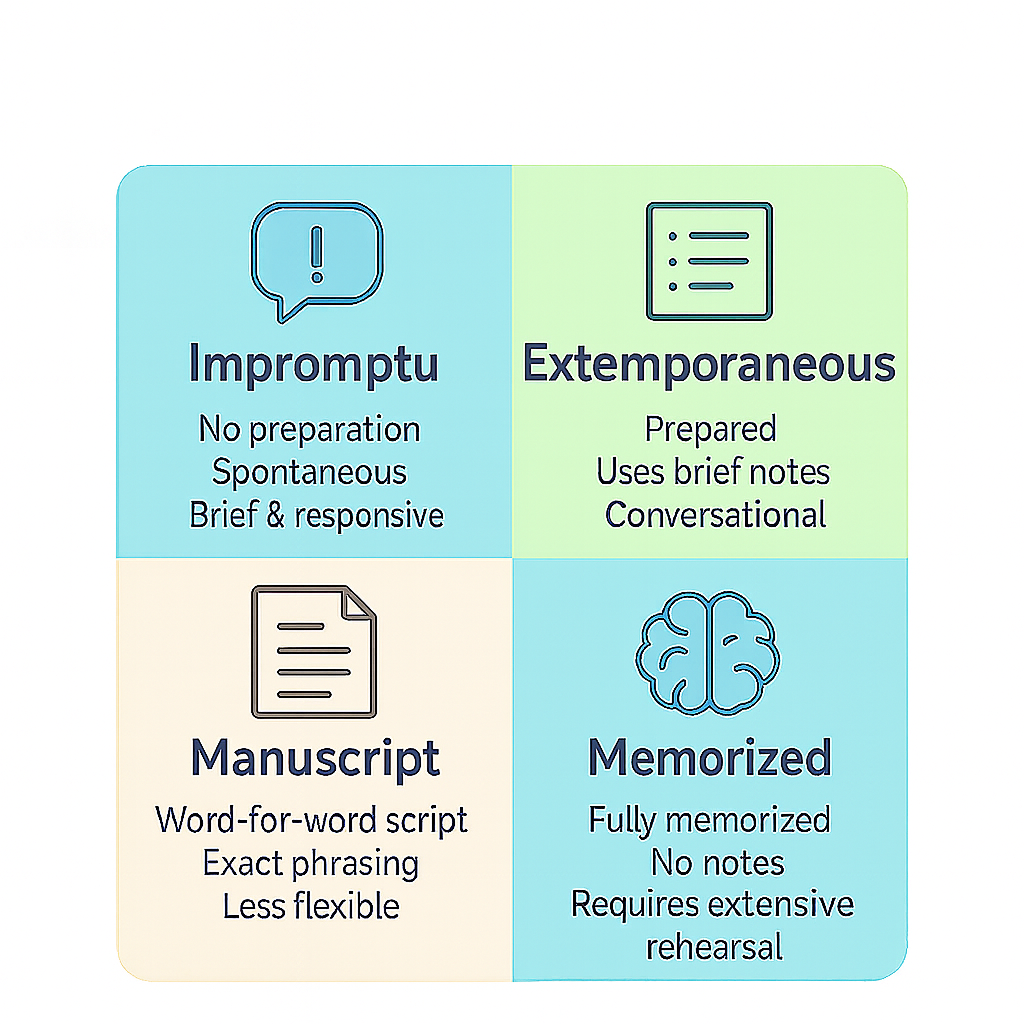

Figure 13.1 Four Methods of Speech Delivery

Image Long Description

This image visually presents four types of speech delivery styles, arranged in a 2×2 grid, each with an icon and a short description:

- Impromptu (top-left, speech bubble icon):

- No preparation

- Spontaneous

- Brief & responsive

- Extemporaneous (top-right, checklist icon):

- Prepared

- Uses brief notes

- Conversational

- Manuscript (bottom-left, document icon):

- Word-for-word script

- Exact phrasing

- Less flexible

- Memorized (bottom-right, brain icon):

- Fully memorized

- No notes

- Requires extensive rehearsal

Each quadrant is color-coded to visually distinguish the styles, offering a clear summary of the pros and cons of each approach.

Text Transcription

- Impromptu

- No preparation

- Spontaneous

- Brief & responsive

- Extemporaneous

- Prepared

- Uses brief notes

- Conversational

- Manuscript

- Word-for-word script

- Exact phrasing

- Less flexible

- Memorized

- Fully memorized

- No notes

- Requires extensive rehearsal

Impromptu Speaking

Impromptu speaking is the presentation of a short message without advance preparation. Impromptu speeches often occur when someone is asked to “say a few words” or give a toast on a special occasion. You have probably done impromptu speaking many times in informal, conversational settings without even realizing the impromptu. In this speech class in which you are enrolled, you speak impromptu when the instructor asks you a question for which you are to provide the answer. Self-introductions in group settings are other examples of impromptu speaking: “Hi, my name is Steve, and I’m a volunteer with the Homes for the Brave program.” Another example of impromptu speaking occurs when you answer a question such as, “What did you think of the documentary?”

The advantage of this kind of speaking is that it’s spontaneous and responsive in an animated group context. The disadvantage is that you are given little or no time to contemplate the central theme of the message and be able to prepare organized and supported main points of a speech. As a result, the message may be disorganized and difficult for listeners to follow. Impromptu speeches are generally most successful when they are brief and focus on a single point.

You can master the impromptu speech by just knowing a few simple tips and tactics in the short time you have when preparing for the impromptu delivery:

- Take a moment to collect your thoughts. You can even quickly write them on a piece of paper so you do not forget them.

- Plan the main point you want to make to this particular audience.

- Thank the person for inviting you to speak.

- Make your main point as briefly as you can while still covering it adequately at a pace your listeners can follow.

- Thank the person again for the opportunity to speak.

- Stop talking! Avoid going on and on and repeating yourself just to fill time. This is called redundancy and the audience will tune you out.

Extemporaneous Speaking

Extemporaneous speaking is the presentation of a carefully planned and rehearsed speech, spoken in a conversational manner, using brief notes. By using brief notes rather than a full manuscript, the extemporaneous speaker can establish and maintain eye contact with the audience and assess how well the audience is understanding the speech as it progresses. The opportunity to assess is also an opportunity to restate more clearly any idea or concept that the audience seems to have trouble grasping.

For instance, suppose you are speaking about workplace safety and you use the term “sleep deprivation” (lack of sleep). If you notice your audience’s eyes glazing over this term, this might not be a result of their own sleep deprivation, but rather an indication of their uncertainty about what you mean. If this happens, you can add a short explanation; for example, “sleep deprivation is sleep loss serious enough to threaten one’s cognition, hand-to-eye coordination, judgment, and emotional health.” You might also (or instead) provide a concrete example to illustrate the idea. Then you can resume your message, having clarified an important concept without disconnecting the audience from your message.

Speaking extemporaneously has advantages. It promotes the likelihood that you, the speaker, will be perceived as knowledgeable and credible. In addition, your audience is likely to pay better attention to the message because you are engaging the audience verbally and you are including nonverbal gestures at key points of the presentation. The disadvantage of extemporaneous speaking is that it requires a great deal of preparation for both the verbal and the nonverbal components of the speech. Adequate preparation cannot be achieved the day before or the day of your scheduled presentation. One key warning here: if you are given only a day or two to prepare for a speech and you are not certain that you can be adequately prepared for the occasion, you should politely decline the opportunity for another time when you have more time to prepare. Being thrust into a situation where your credibility is at stake and where the audience’s expectations are high can prove disastrous. Extemporaneous speaking is a most popular mode of delivery and it should be given the time and focus out of respect for the audience and you, too!

Because extemporaneous speaking is the style used in the great majority of public speaking situations, most of the information in this chapter is targeted to this kind of speaking.

Speaking from a Manuscript

Manuscript speaking is the word-for-word delivery of a written message. In a manuscript speech, the speaker maintains his or her attention on the printed page except when using visual aids needing to direct the audience’s attention to something else that accompanies the speech, such as a prop used for emphasis.

The advantage to reading from a manuscript is the exact repetition of original words. As we mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, in some circumstances, this can be extremely important. For example, reading a statement about your organization’s legal responsibilities to customers may require that the original words be exact. This means that you still need to practice reading the manuscript to avoid mispronouncing unfamiliar words or phrases or names.

However, there are challenges involved in manuscript speaking. First, it’s typically an uninteresting way to present. Unless the speaker has rehearsed the reading as a complete “stage-like performance,” animated with vocal expression and gestures (as poets do in a poetry slam and actors do in a reader’s theater), the presentation tends to be dull and boring. Keeping one’s eyes glued to the script precludes eye contact with the audience that promotes disengagement from you, the speaker. For this kind of “straight” manuscript speech to hold audience attention, the audience must be already interested in the message before the delivery begins, and that can be hard to discern because not all audiences are created equal. Keep in mind that manuscript speaking does not preclude using eye contact. Take the opportunity to look at the audience at various times during your reading of the manuscript: before important points for emphasis, at the end of paragraphs, and between transitions from parts of the speech, such as between the main points and just before the conclusion.

It is worth noting that professional speakers, actors, news reporters, and even elected officials often read from an autocue device called a Teleprompter, especially when appearing on television, where eye contact with the camera is crucial. However, using this device does not come without extensive practice so that it appears the person is not reading but that it almost appears as if the reporter or actor or official knows the content by memory. With practice, a speaker can achieve a conversational tone and give the impression of speaking extemporaneously while using an autocue device. However, success in this medium depends on two factors: (1) the speaker is already an accomplished public speaker who has learned to use a conversational tone while delivering a prepared script, and (2) the speech is written in a style that sounds conversational.

In conclusion, manuscript delivery, especially for students just beginning to sharpen their speaking skills, should only be used for short speeches, such as a wedding or anniversary toast

Speaking from Memory

Memorized speaking is the direct recitation of a written message that the speaker has committed to memory. Actors, of course, recite from memory whenever they perform from a script in a stage play, television program, or movie scene. When it comes to speeches, however, memorization can be useful when the message needs to be exact and the speaker doesn’t want to be confined by notes.

The advantage to memorization is that it enables you to maintain eye contact with the audience throughout the speech. Being free of notes means that you can move freely around the stage or room and that you can gesture freely. If your speech uses visuals like slides or props, this freedom is even more of an advantage. However, there are some real and potential challenges to this mode of speaking. First, unless you also plan and memorize every vocal cue (the subtle but meaningful variations in speech delivery, which can include the use of pitch, tone, volume, and pace which we will define later in this chapter), gesture, and facial expressions, your presentation will be flat and uninteresting. Even the most fascinating topic will suffer. You might end up speaking in a monotone or a sing-song repetitive delivery pattern. You might also present your speech in a rapid rushed style that fails to emphasize the most important points. Second, if you lose your place and start trying to ad lib, the contrast in your style of delivery will alert your audience that something is wrong and that you may have forgotten your content. More frighteningly, if you go completely blank during the presentation, it will be extremely difficult to find your place and keep going, all of which impacts your credibility and knowledge of the topic.

You Try It: Check Your Understanding