13.4 How to Practice and Preparation Make for Professional Presentation

Rosemary Martinelli

Learning Objectives

- Explain why having a strong conversational quality is important for effective public speaking

- Explain the importance of eye contact in public speaking

- Define vocalics and differentiate among the different factors of vocalics

- Explain effective physical manipulation during a speech

- Understand how to practice effectively for good speech delivery

- Use AI feedback tools to refine speech delivery and improve confidence

How to speak so that people want to listen (Video).

Julian Treasure. TEDGlobal 2013. All Rights Reserved.

There is no foolproof recipe for good delivery. Each of us is unique and we each embody different experiences and interests. This means each person has an approach, or a style, that is effective for that person. This further means that anxiety can accompany even the most carefully researched and interesting message. Even when we know our messages are strong and well-articulated on paper, it is difficult to know for sure that our presentation will also be good. This is what worries most student speakers, but know that anxiety or worry when giving a speech is completely normal and there are ways to combat that anxiety, which we will review here.

There is no foolproof recipe for good delivery. Each of us is unique and we each embody different experiences and interests. This means each person has an approach, or a style, that is effective for that person. This further means that anxiety can accompany even the most carefully researched and interesting message. Even when we know our messages are strong and well-articulated on paper, it is difficult to know for sure that our presentation will also be good. This is what worries most student speakers, but know that anxiety or worry when giving a speech is completely normal and there are ways to combat that anxiety, which we will review here.

We are still obligated to do our best out of respect for the audience and their needs. Fortunately, there are some tools that can be helpful to you even the very first time you present a speech. You will continue developing your skills each time you put them to use and can experiment to find out which combination of delivery elements is most effective for you. Just as with anything, the more speeches and presentations you give—either inside or outside of the classroom environment—the more accomplished and professional you will be when addressing an audience.

Time is a valuable commodity. Failing to prepare and deliver a speech within the time allotted to you wastes an audience’s time, shows disrespect for the people who invited you to speak (and that includes your professors and your co-workers), and detracts from your credibility as a speaker.

What Makes Good Delivery

The more you care about your topic, the greater your motivation to present it well. Good delivery is a process of presenting a clear, coherent message in an interesting way. Communication scholar Stephen E. Lucas tells us:

Good delivery…conveys the speaker’s ideas clearly, interestingly, and without distracting the audience. Most audiences prefer delivery that combines a certain degree of formality with the best attributes of good conversation—directness, spontaneity, animation, vocal and facial expressiveness, and a lively sense of communication (Lucas, 2009).

Many writers on the nonverbal aspects of delivery have cited the findings of psychologist Albert Mehrabian, asserting that the bulk of an audience’s understanding of the message is based on nonverbal communication. Specifically, Mehrabian is often credited with finding that when audiences decoded a speaker’s meaning, the speaker’s face conveyed 55 percent of the information, the vocals/verbals conveyed 38 percent, and the words themselves conveyed just 7 percent (Mehrabian, 1972). Although numerous scholars, including Mehrabian himself, have stated that his findings are often misinterpreted (Mitchell), scholars and speech instructors do agree that nonverbal communication and speech delivery are extremely important to effective public speaking.

In this section of the chapter, we will explain six elements of good delivery: conversational style, conversational quality, eye contact, vocalics, physical manipulation, and variety. And since delivery is only as good as the practice that goes into it, we conclude with some tips for effective use of your practice time.

Conversational Style

Conversational style is a speaker’s ability to sound expressive and to be perceived by the audience as natural. It’s a style that approaches the way you normally express yourself in a much smaller group than your classroom audience. This means that you want to avoid having your presentation come across as academic, stilted or overly exaggerated. You might not feel natural while you’re using a conversational style, but for the sake of audience preference and receptiveness, you should do your best to appear natural. It might be helpful to remember that the two most important elements of the speech are the message and the audience. You are the conduit with the important role of putting the two together in an effective way. Your audience should be thinking about the message, not your delivery.

Stephen E. Lucas defines conversational quality as the idea that “no matter how many times a speech has been rehearsed, it still sounds spontaneous” [emphasis in original] (Lucas, 2009). No one wants to hear a speech that is so well rehearsed that it sounds fake or robotic. This means you need to strike a balance between the two—knowing the content but still presenting it with passion, enthusiasm and professionalism. One of the hardest parts of public speaking is rehearsing to the point where it can appear to your audience that the thoughts are magically coming to you while you’re speaking, but in reality you’ve spent a great deal of time thinking through each idea. When you can sound conversational, people pay attention and respect your credibility.

Eye Contact—Staying Connected to the Audience

Eye contact is a speaker’s ability to have visual contact with everyone in the audience. Your audience should feel that you’re speaking to them—speaking to each of them individually, even though you are speaking to the group–not simply uttering main and supporting points. If you are new to public speaking, you may find it intimidating to look audience members in the eye, but if you think about speakers you have seen who did not maintain eye contact, you’ll realize why this aspect of speech delivery is important. Without eye contact, the audience begins to feel invisible and unimportant, as if speakers are just speaking to hear their own voices. Eye contact lets your audience feel that your attention is on them, not solely on the notes you may have in front of you.

Learn the 80/20 rule for speeches and presentations: practice speaking as many words as possible without looking at your notes. Strive for 80% engaging with the audience and 20% referring to your notes. This is supported by your ability to actually know your opening and closing remarks by memory so that the audience connects with you immediately and at the end, remembers you positively!

If you find the gaze of your audience too intimidating, you might feel tempted to resort to “faking” eye contact with them by looking at the wall just above their heads or by sweeping your gaze around the room instead of making actual eye contact with individuals in your audience until it becomes easier to provide real contact. The problem with fake eye contact is that it tends to look mechanical. Another problem with fake attention is that you lose the opportunity to assess the audience’s understanding of your message. Know this: audiences know when you are avoiding their focus. If you are looking off to the back of the room where there is no audience, people who are sitting in the front of the room will take notice. You cannot avoid the eye contact, no matter how hard you try!

Sustained eye contact with your audience is one of the most important tools toward effective delivery. O’Hair, Stewart, and Rubenstein note that eye contact is mandatory for speakers to establish a good relationship with an audience (O’Hair, Stewart, & Rubenstein, 2001). Whether a speaker is speaking before a group of five or five hundred, the appearance of eye contact is an important way to bring an audience into your speech. Eye contact can be a powerful tool. It is not simply a sign of sincerity, a sign of being well prepared and knowledgeable, or a sign of confidence; it also has the power to convey meanings. Arthur Koch tells us that all facial expressions “can communicate a wide range of emotions, including sadness, compassion, concern, anger, annoyance, fear, joy, and happiness” (Koch, 2010).

One key tip to engage with the audience and retain eye contact is to pick out a person in each section of the audience and deliver your speech to each of those individuals. This keeps your eyes moving about the audience and helps to sustain audience engagement because it appears that you are looking at everyone in the group. Try this the next time you give a speech. The more you speak in front of larger audiences, the more comfortable you will be with maintaining eye contact that eventually you will be able to gaze throughout the room with comfort and ease in delivering your speech.

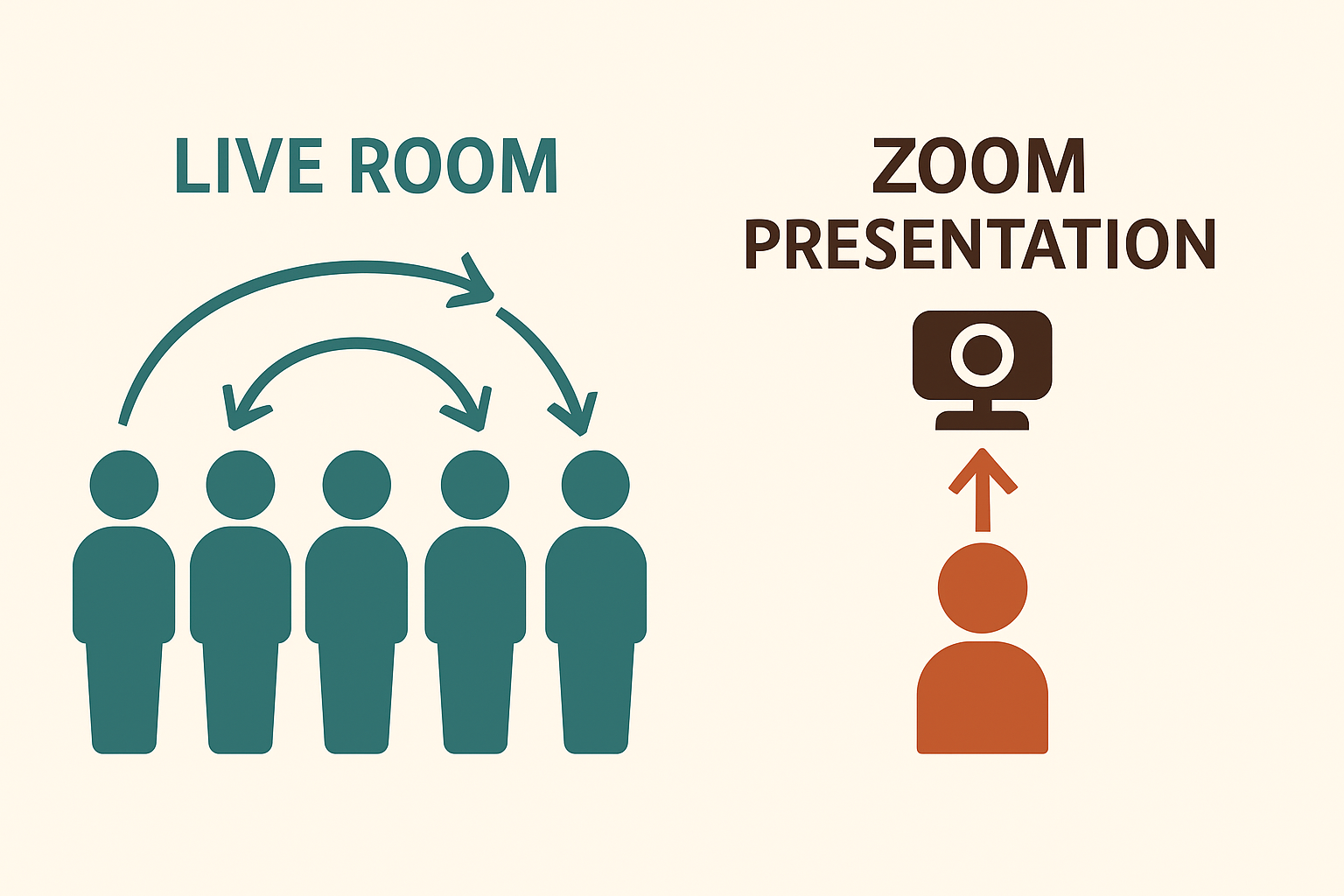

Figure 13.2 Eye Contact for Live and Virtual Audiences

Image Long Description

The image is split into two sections:

On the left side, titled “LIVE ROOM,” there are five teal-colored human icons standing side by side. Arrows curve between them, indicating multi-directional communication and interaction among the audience members.

On the right side, titled “ZOOM PRESENTATION,” there is a single rust-colored person icon facing a webcam icon above it, with a single upward arrow pointing from the person to the camera. This symbolizes one-way communication directed toward the camera for remote audiences.

Text Transcription

LIVE ROOM

ZOOM PRESENTATION

This is not to say that you may never look at your notecards. On the contrary, one of the skills in extemporaneous speaking is the ability to alternate one’s gaze between the audience and one’s notes. Rehearsing your presentation in front of a few friends should help you develop the ability to maintain eye contact with your audience while referring to your notes. When you are giving a speech that is well prepared and well rehearsed, you will only need to look at your notes occasionally. This is an ability that will develop even further with practice. Your public speaking course is your best chance to get that practice.

Effective Use of Vocalics

Vocalics, also known as paralanguage, is the subfield of nonverbal communication that examines how we use our voices to communicate orally. This means that you speak loudly enough for all audience members (even those in the back of the room) to hear you clearly, and that you enunciate clearly enough to be understood by all audience members (even those who may have a hearing impairment or who may be English-language learners.) If you tend to be soft-spoken, you will need to practice using a louder volume level that may feel unnatural to you at first. For all speakers, good vocalic technique is best achieved by facing the audience with your chin up and your eyes away from your notecards and by setting your voice at a moderate speed. Effective use of vocalics also means that you make use of appropriate:

- Pitch

- Pauses

- Vocal Variety

- Pronunciation

- Enunciation

- Articulation

- Rate

- Volume

If you are an English-language learner/English as a second language learner and feel apprehensive about giving a speech in English, there are two things to remember: first, you can meet with a reference librarian to learn the correct pronunciations of any English words you are unsure of; and second, the fact that you have an accent means you speak more languages than most Americans, which is an accomplishment of which you should be proud.

If you are one of the many people with a stutter or other speech challenge, you undoubtedly already know that there are numerous techniques for reducing stuttering and improving speech fluency and that there is no one agreed-upon “cure.” The Academy Award–winning movie The King’s Speech did much to increase public awareness of what a person with a stutter goes through when it comes to public speaking. It also prompted some well-known individuals who stutter, such as television news reporter John Stossel, to go public about their stuttering (Stossel, 2011). If you have decided to study public speaking in spite of a speech challenge, we commend you for your efforts and encourage you to work with your speech instructor to make whatever adaptations work best for you. These adaptations may require extra time for speech and presentation preparation, simple slides that enhance your presentation and do not overwhelm your audience, and a microphone to help you gain additional volume in your words.

Volume

Volume refers to the loudness or softness of a speaker’s voice. As mentioned, public speakers need to speak loudly enough to be heard by everyone in the audience. In addition, volume is often needed to overcome ambient noise, such as the hum of an air conditioner or the dull roar of traffic passing by the space in which you are speaking. In addition, you can use volume strategically to emphasize the most important points in your speech. Select these points carefully; if you emphasize everything, nothing will seem important. You also want to be sure to adjust your volume to the physical setting of the presentation. If you are in a large auditorium and your audience is several yards away, you will need to speak louder. If you are in a smaller space, with the audience a few feet away, you want to avoid overwhelming your audience with shouting or speaking too loudly.

Remember, too, that a microphone can help with amplify your words, but it will not bring more volume to softness in your voice. That is related to pitch.

Pitch

Pitch refers to the highness or lowness of a speaker’s voice. Some speakers have deep voices and others have high voices. As with one’s singing voice range, the pitch of one’s speaking voice is determined to a large extent by physiology (specifically, the length of one’s vocal folds, or cords, and the size of one’s vocal tract). We all have a normal speaking pitch where our voice is naturally settled, which is the pitch where we are most comfortable speaking. Most professional speakers advise speaking at the pitch that feels natural to you.

While our voices may be generally comfortable at a specific pitch level, we all have the ability to modulate, or move, our pitch up or down. In fact, we do this all the time. When we change the pitch of our voices, we are using inflections. Just as you can use volume strategically, you can also use pitch inflections to make your delivery more interesting and emphatic. If you ordinarily speak with a soprano voice, you may want to drop your voice to a slightly lower range to call attention to a particular point. How we use inflections can even change the entire meaning of what we are saying.

For example, try saying the sentence “I love public speaking” or “I did not say you hurt my feelings,” with a higher pitch or stronger emphasis on one of the words, a different word, each time you say the sentences. First raise the pitch on “I,” then say it again with the pitch raised on “love” or “did not,” and so on. “I love public speaking” conveys a different meaning from “I love public speaking,” or “I did not say you hurt my feelings” is different from “I did not say YOU hurt my feelings.” Makes a difference, doesn’t it?

There are some speakers who don’t change their pitch at all while speaking, which is called speaking in a monotone. Have you seen this happen when you were in the audience listening to a speaker? Unfortunately, it is quite common. While very few people are completely monotone, some speakers slip into monotone patterns because of nerves or from reading their notes. One way to ascertain whether you sound monotone is to record your voice and see how you sound. If you notice that your voice doesn’t fluctuate very much, you will need to be intentional in altering your pitch to ensure that the emphasis of your speech isn’t completely lost on your audience.

Finally, resist the habit of pitching your voice “up” at the ends of sentences or trailing off your voice at the end of your sentences. It makes them sound like questions instead of statements or the full meaning of what you are trying to say gets lost on the audience because they cannot hear you. This habit can be disorienting and distracting, interfering with the audience’s ability to focus entirely on the message. The speaker sounds uncertain or sounds as though they are seeking the understanding or approval of the listener. It hurts the speaker’s credibility and it needs to be avoided. The effective use of pitch is one of the keys to an interesting delivery that will hold your audience’s attention.

Rate or Speed at Which You Speak

Rate is the speed or pace at which you are speaking. To keep your speech delivery interesting, your rate should vary but not so fast or not so slow that the audience gets lost in what you are saying. If you are speaking extemporaneously, your rate will naturally fluctuate. If you’re reading a manuscript, your delivery is less likely to vary. Because rate is an important tool in enhancing the meanings in your speech, you do not want to give a monotone drone or a rapid “rushed staccato-style” delivery. Your rate should be appropriate for your topic and your points. A rapid, lively rate can communicate such meanings as enthusiasm or urgency. A slower, moderated rate can convey respect, seriousness, or careful reasoning. By varying rapid and slower rates within a single speech, you can emphasize your main points and keep your audience interested.

Effective Use of Pauses While Avoiding the Uhs and Ums and Filler Words

Pauses are brief breaks in a speaker’s delivery that can show emphasis and enhance the clarity of a message. In terms of timing, the effective use of pauses is one of the most important skills to develop but sometimes you may find it uncomfortable to have silence in the room during a pause. Some speakers become uncomfortable very quickly with the pause and then they feel the need to fill the silence with what is often called “vocal graffiti”: uhs, and ums and filler words like “like,” “such as,” “you know,” “all that stuff,” and overuse of the word “that,” just to keep the sound going forward from you, the speaker, and to avoid the dead air” that speakers often thing pauses can cause. If the speaker is uncomfortable, the discomfort can transmit itself to the audience. public speaking is avoiding the use of verbal surrogates or “filler” words used as placeholders for actual words. You might be able to get away with saying “um” as many as two or three times in your speech before it becomes distracting, but the same cannot be said of “like,” “you know” and the others listed here.

All of this does not mean that you should avoid using pauses. Your ability to use them confidently will increase with practice. Some of the best comedians use the well-timed pause to powerful and hilarious effect in their stand-up comedy routines. Although your speech will not be a comedy routine, pauses are still useful for emphasis, especially when combined with a lowered pitch and rate to emphasize the important point you do not want your audience to miss.

You Try It: Vocal Variety, Pitch, Rate, Pauses

Activity Introduction: Effective speakers use vocalics such as volume, pitch, rate, pauses to make messages clear and engaging. In this scenario-based quiz, you’ll choose the best vocalics technique for each situation.

Activity Instructions: Read each delivery scenario and select the vocalics strategy that would best improve clarity, emphasis, or engagement.

Wrap Up: By choosing effective vocal strategies, you enhance your delivery and help listeners stay engaged and understand your message clearly.

Vocal Variety to Keep the Audience Engaged

Vocal variety has to do with changes in the vocalics we have just discussed: volume, pitch, rate, and pauses. No one wants to hear the same volume, pitch, rate, or use of pauses over and over again in a speech. That is just boring and monotonous! When you think about how you sound in a normal conversation, your use of volume, pitch, rate, and pauses are all done spontaneously. If you try to over-rehearse your vocalics, your speech will end up sounding artificial. Vocal variety should flow naturally from your wish to speak with expression. In that way, it will animate your speech and invite your listeners to understand your topic the way you do. Good vocal variety can also help you maintain a conversational tone and pace that keeps your audience engaged with what you have to say.

Pronunciation and Enunciation and Articulation

These three elements of vocalization are often confused with one another, but, in essence, they are relatively interconnected. Pronunciation refers to how a word is spoken, including specific sounds and patterns. Correct pronunciation ensures that the word is recognized and understood, as intended. This is especially important when pronouncing the names of cities—which may be pronounced a specific way due to regional accents by the people who live in that area. Never assume the pronunciation of a city or town or even the name of a person. Always take the time to double-check the pronunciation. the conventional patterns of speech used to form a word.

Word pronunciation is important for two reasons: first, mispronouncing a word your audience is familiar with will harm your credibility as a speaker; and second, mispronouncing a word they are unfamiliar with can confuse and even misinform them. If there is any possibility at all that you don’t know the correct pronunciation of a word, find out. Check into the way words are pronounced in the local community. Double-check by researching through a library or online through a reputable website. College libraries have a variety of credible sources from which you can work. Many online dictionaries provide free sound files illustrating the pronunciation of words.

Enunciation is the clarity and distinctness with which words are spoken. It is the opposite of mumbling and slurring words and syllables.

Finally, articulation involves the physical production of speech sounds and how the mouth and throat produce those sounds. Proper articulation is necessary for clear and precise speech, impacting both pronunciation and enunciation.

People have often commented on the mispronunciation of words by highly-educated public speakers, including elected officials, celebrities and even TV reporters who might be new to a certain media market. There have been speech class examples, as well. For instance, a student giving a speech on the Greek philosopher Socrates mispronounced his name at least eight times during her speech. This mispronunciation created a situation of great awkwardness and anxiety for the audience which knew the pronunciation was incorrect. Everyone felt embarrassed and the teacher, opting not to humiliate the student in front of the class, could not say anything out loud, instead providing a private written comment at the end of class.

Remember, never assume that you think you can figure out the pronunciation, articulation or enunciation of words and phrases. Always ask for clarification while you are preparing your speech because the obvious may not be so obvious.

Effective Non Verbals and Body Language to Enhance a Presentation

In addition to using your voice effectively, a key to effective public speaking is physical manipulation, or the use of the body and face to emphasize meanings or convey meanings during a speech. While we will not attempt to give an entire discourse on nonverbal communication, we will discuss a few basic aspects of physical manipulation: posture, body movement, facial expressions, and dress. These aspects add up to the overall physical dimension of your speech, which we call self-presentation. Studies have shown that if verbals and nonverbals—like facial expressions and gestures—conflict, the audience will likely believe the nonverbals versus the actual speech content. Always practice them both in preparation for any speech. Using nonverbals helps the audience to understand and remember your message.

Posture

“Stand up tall! Look confident and professional!” You have likely heard this statement from a parent or a teacher at some point in your life. The fact is, posture is actually quite important. When you stand up straight, you communicate to your audience, without saying a word, that you hold a position of power and take your position seriously. If however, you are slouching, hunched over, or leaning on something (including that lectern or podium) you could be perceived as ill-prepared, anxious, lacking in credibility, or not serious about your responsibilities as a speaker. You also show lack of respect for your audience which has come to hear what you have to say. While speakers often assume more casual posture as a presentation continues (especially if it is a long one, such as a ninety-minute class lecture), it is always wise to start by standing up straight and putting your best foot forward. Position yourself toward the audience. Remember, you only get one shot at making a first impression, and your body’s orientation is one of the first pieces of information audiences use to make that impression.

Body Language and Nonverbal Emphases

Unless you are stuck behind a podium or lectern because of the need to use a non-movable microphone, you should never stand in one place during a speech. However, movement during a speech should also not resemble pacing the floor. Movement should have meaning to what you are presenting. As speakers, we must be mindful of how we go about moving while speaking. One common method for easily integrating some movement into your speech is to take a few steps any time you transition from one idea to the next. By only moving at transition points, not only do you help focus your audience’s attention on the transition from one idea to the next, but you also are able to increase your nonverbal immediacy by getting closer to different segments of your audience.

Body movement also includes gestures. These should be neither overdramatic nor subdued. They should be meaningful and help to enhance the elements of your speech. At one extreme, arm-waving and fist- pounding will distract from your message and reduce your credibility. At the other extreme, refraining from the use of gestures is the waste of an opportunity to suggest emphasis, enthusiasm, or other personal connection with your topic. Even gesturing toward your slides as they are projected on a screen during your presentation can be a strong nonverbal form of movement during that helps the audience to follow along and further understand what you are saying.

There are many ways to use gestures. The most obvious are hand gestures, which should be used in moderation at carefully selected times in the speech. If you overuse gestures, they lose meaning. Many late-night comedy parodies of political leaders include patterned, overused gestures or other delivery habits associated with a particular speaker. However, the well-placed use of simple, natural gestures to indicate emphasis, direction, size is usually effective. Normally, a gesture with one hand is enough. Rather than trying to have a gesture for every sentence, use just a few well-planned gestures. It is often more effective to make a gesture and hold it for a few moments than to begin waving your hands and arms around in a series of gestures.

Finally, just as you should avoid pacing aimlessly around the room during your speech, you will also want to avoid other distracting movements when you are speaking. Many speakers have unconscious mannerisms such as twirling their hair, putting their hands in and out of their pockets, jingling their keys, licking their lips, playing with a paper clip or clicking a pen while speaking. As with other aspects of speech delivery, practicing in front of others will help you become conscious of such distractions and plan ways to avoid them.

Facial Expressions as Effective NonVerbals

Faces are amazing things and convey so much information. As a speaker, you should always be acutely aware of what your face looks like while speaking. Often the only way you can critically evaluate what your face is doing while you are speaking is to watch a recording of your speech. Use a smart phone to record yourself or stand in front of a mirror and watch yourself practice your speech. If your campus has a video studio, schedule a time to have your presentation recorded so you can view it to critique yourself.

This is especially important during virtual presentations. You are on the screen for a rather lengthy period of time, so having an expressionless talking head of yourself in a box on the screen can certainly cause your virtual audience to “log out.” Facial expressions are front and center in a virtual presentation, as often the expressions are the only form of nonverbals that accompany the content of your speech because you rarely have the ability to use full body movements while you are seated before the camera on your computer or laptop.

Now, that said, be careful of two EXTREMEs to avoid no matter the modality of your speech: no facial expression and over-animated facial expressions. First, you do not want to have a completely blank face while speaking, whether virtually, as just noted here, but especially when you are standing in front of a crowded room with an eager audience. Some people just do not show much emotion with their faces naturally, but this blankness is often increased when the speaker is nervous. Audiences will react negatively to the message of such a speaker because they will sense that something is amiss. If a speaker is talking about the joys of a summer vacation and the face doesn’t show any excitement, the audience is going to be turned off to the speaker and the message. On the other extreme end is the speaker whose face looks like that of an exaggerated cartoon character. Instead, your goal is to show a variety of appropriate facial expressions while speaking. Relate your expressions to the content of the speech.

Like vocalics and gestures, facial expression can be used strategically to enhance meaning. A smile or pleasant facial expression is generally appropriate at the beginning of a speech to indicate your wish for a good transaction with your audience. However, you should not smile throughout a serious speech topic such as a health and medical speech, a speech on a serious community issue of an environmental problem. An inappropriate smile creates confusion about your meaning and may make your audience feel uncomfortable. On the other hand, a serious scowl might look hostile or threatening to audience members and become a distraction from the message. If you keep the meaning of your speech foremost in your mind, you will more readily find the balance in facial expression.

Another common problem some new speakers have is showing only one expression. If you are excited in a part of your speech, you should show excitement on your face. On the other hand, if you are at a serious part of your speech, your facial expressions should be serious.

You Try It: Spot the Nonverbal Communications

Activity Introduction: Nonverbal communication like posture, gestures, eye contact, facial expressions shape how your audience perceives your confidence and credibility. This activity helps you identify effective (and ineffective) nonverbal choices.

Activity Instructions: Read the short description and highlight the word or phrase that demonstrates effective nonverbal delivery. Focus on behaviors that reflect strong physical presence, expressive engagement, and audience connection.

Wrap Up: Identifying effective nonverbal skills helps you develop stronger physical presence and strengthens your audience connection during speech delivery.

Attire as A Form of Presentation

While there are no clear-cut guidelines for how you should dress for every speech you’ll give, dress is still a very important part of how others will perceive you (again, it’s all about the first impression). If you want to be taken seriously, you must present yourself seriously. While you may not need to dress up every time you give a speech, there are definitely times when wearing a suit is appropriate.

One general rule you can use for determining dress is the “step-above rule,” which states that you should dress one step above your audience. If your audience is going to be dressed casually in shorts and jeans, then wear nice casual clothing such as a pair of neatly pressed slacks and a collared shirt or blouse. If, however, your audience is going to be wearing “business casual” attire, then you should probably wear a sport coat, a dress, or a suit. The goal of the step-above rule is to establish yourself as someone to be taken seriously. On the other hand, if you dress two steps above your audience, you may put too much distance between yourself and your audience, coming across as overly formal or even arrogant.

Another general rule for dressing is to avoid distractions in your appearance. Overly tight or revealing garments, over-the-top hairstyles or makeup, jangling jewelry, or a display of tattoos and piercings can serve to draw your audience’s attention away from your speech. Remembering that your message is the most important aspect of your speech, so keep that message in mind when you choose your clothing and accessories. Dressing appropriately, even during a virtual presentation, enhances your speech and gives you the charisma and credibility that is encompassed in the “ethos” that we noted earlier in this chapter and in this book.

Self-Presentation As A Form of Professionalism

When you present your speech, you are also presenting yourself. Self-presentation, sometimes also referred to as poise or stage presence, is determined by how you look, how you stand, how you walk to the lectern, and how you use your voice and gestures. Your self-presentation can either enhance your message or detract from it. Worse, a poor self-presentation can turn a good, well- prepared speech into a forgettable waste of time. You want your self-presentation to support your credibility and improve the likelihood that the audience will listen with interest.

Your personal appearance should reflect the careful preparation of your speech. Your personal appearance is the first thing your audience will see, and from it, they will make inferences about the speech you’re about to present.

Variety Is the Spice of Every Speech

One of the biggest mistakes novice public speakers make is to use the same gesture over and over again during a speech. While you don’t want your gestures to look fake, you should be careful to include a variety of different nonverbal components while speaking. You should make sure that your face, body and words are all working in conjunction with each other to support your message. Movement should always have meaning!

Practice Effectively and Practice Often

You might get away with presenting a hastily practiced speech for one of your college classes, but the speech will not be as good as it could be if you had taken the time to practice. In order to develop your best speech delivery, you need to practice—and use your practice time effectively. Practicing does not mean reading over your notes, mentally running through your speech, or even speaking your speech aloud over and over. Instead, you need to practice with the goal of identifying the weaknesses in your delivery, improving upon them, and building good speech delivery habits.

When you practice your speech, place both your feet in full, firm contact with the floor to keep your body from swaying side to side. Some new public speakers find that they don’t know what to do with their hands during the speech. Your practice sessions should help you get comfortable. When you’re not gesturing, you can rest your free hand lightly on a lectern or simply allow it to hang at your side. Since this is not a familiar posture for most people, it might feel awkward, but in your practice sessions, you can begin getting used to it.

Seek Input from Others

Because we can’t see ourselves as others see us, one of the best ways to improve your delivery is to seek constructive criticism from others. This, of course, is an aspect of your public speaking course, as you will receive evaluations from your instructor and possibly from your fellow students. However, by practicing in front of others before it is time to present your speech, you can anticipate and correct problems so that you can receive a better evaluation when you give the speech “for real.” Be careful, however, that your classroom colleagues are not just giving you positive feedback because they do not want to be critical of your presentation. They should be honest with you and you with them when you are evaluating their speeches, too. Ask: what did you do well…where can you improve…was the message lost through the use of incorrect nonverbals that did not complement the speech content…were the vocals strong and clear?

If your practice observers seem reluctant to offer useful criticisms, ask questions. How was your eye contact? Could they hear you? Was your voice well modulated? Did you mispronounce any words? How was your posture? Were your gestures effective? Did you have any mannerisms that you should learn to avoid? Because peers are sometimes reluctant to say things that could sound critical, direct questions are often a useful way to help them speak up and share input.

If you learn from these practice sessions that your voice tends to drop at the ends of sentences, make a conscious effort to support your voice as you conclude each main point. If you learn that you have a habit of clicking a pen, make sure you don’t have a pen with you when you speak or that you keep it in your pocket. If your practice observers mention that you tend to hide your hands in the sleeves of your shirt or jacket, next time wear short sleeves or roll your sleeves up before beginning your speech. If you constantly put your hands in your pockets, avoid wearing clothing with pockets. If you learn through practice that you tend to sway or rock while you speak, you can consciously practice and build the habit of not swaying.

When it is your turn to give feedback to others in your group, assume that they are as interested in doing well as you are. Give feedback in the spirit of helping their speeches be as good as possible.

Be prepared, too, for audiences to complete surveys of speeches given at conferences or luncheons or other programs where you may be the speaker. The feedback audiences provide can be extremely valuable for the next time you are expected to give a speech on the same topic.

Use Audio and/or Video to Record Yourself

Technology has made it easier than ever to record yourself and others using the proliferation of electronic devices people are likely to own. Video, of course, allows you the advantage of being able to see yourself as others see you, while audio allows you to concentrate on the audible aspects of your delivery. As we mentioned earlier in the chapter, if neither video nor audio is available, you can always observe yourself by practicing your delivery in front of a mirror.

After you have recorded yourself, it may seem obvious that you should watch and listen to the recording. This can be intimidating, as you may fear that your performance anxiety will be so obvious that everyone will notice it in the recording. But students are often pleasantly surprised when they watch and listen to their recordings, as even students with very high anxiety may find out that they “come across” in a speech much better than they expected.

A recording can also be a very effective diagnostic device. Sometimes students believe they are making strong contact with their audiences, but their cards contain so many notes that they succumb to the temptation of reading. By finding out from the video that you misjudged your eye contact, you can be motivated to rewrite your notecards in a way that doesn’t provide the opportunity to do so much reading.

It is most likely that in viewing your recording, you will benefit from discovering your strengths and finding weak areas you can strengthen.

You Try It: Zoom Smart Recording: AI Delivery Check-In

Activity Introduction: AI tools like Zoom’s Smart Recording can give you quick, targeted insights into your delivery, such as your pacing, clarity, filler words, and audience engagement. In this activity, you’ll record a short practice speech and use the AI-generated feedback to identify one improvement you can make right away.

Wrap Up: Zoom’s Smart Recording gives you quick, objective snapshots of your delivery. By identifying one clear improvement and applying it, you take meaningful steps toward stronger, more confident speaking.

Good Delivery Is a Habit, Well-Timed

Luckily, public speaking is an activity that, when done conscientiously, strengthens with practice. As you become aware of the areas where your delivery has room for improvement, you will begin developing a keen sense of what “works” and what audiences respond to.

It is advisable to practice out loud in front of other people several times, spreading your rehearsals out over several days. To do this kind of practice, of course, you need to have your speech finalized well ahead of the date when you are going to give it. During these practice sessions, you must also time your speech to make sure it lasts the appropriate length of time. The last thing you want to do is to give a speech and be oblivious to its length. If you are asked to speak for 10 minutes, practice timing yourself and respect the audience—give them 10 minutes, not five minutes and certainly not 15 minutes. Speakers who do not respect the time allotted for them to speak are projecting a rude and callous disregard for the audience. Guaranteed the audience will not remember the speech content, but the audience will certainly remember a speech that went far too long beyond the allocated time.

Your practice sessions will also enable you to make adjustments to your notecards to make them more effective in supporting your contact with your audience. This kind of practice is not just a strategy for beginners; it is practiced by many highly-placed public figures with extensive experience in public speaking.

Your public speaking course is one of the best opportunities you will have to manage your performance anxiety, build your confidence in speaking extemporaneously, develop your vocal skills, and become adept at self-presentation. The habits you can develop through targeted practice are to build continuously on your strengths and to challenge yourself to find new areas for improving your delivery. By taking advantage of these opportunities, you will gain the ability to present a speech effectively whenever you may be called upon to speak publicly.

You Try It: Practicing your presentation effectively

Activity Introduction: Great delivery comes from intentional and structured practice, not just reading your notes. This activity helps you quickly design a realistic practice plan that follows the recommendations from Section 13.4.

Wrap Up: By creating a quick, targeted practice plan, you prepare yourself for purposeful improvement which builds both confidence and professionalism in your delivery.