2.2: The Ethics Pyramid

Janie Harden Fritz

Learning Objectives

- Explain how the three levels of the ethics pyramid might be used in evaluating the ethical choices of a public speaker or listener

- Evaluate the implications of moderating free speech in digital spaces

- Reflect on potential biases and ethical challenges when using AI to generate speech content

- Evaluate ethical dilemmas presented by AI-generated speech content

- Evaluate the ethical implications of incorporating AI tools during speech preparation

Fritz et al. (2023) note that we live in a moment with disagreement about right and wrong—about what is “good” for humans to be and to do. This disagreement does not mean that we cannot speak meaningfully about ethics; ethical positions come from the moral traditions, or narratives, that guide our lives. Particular religious, political, or philosophical ways of understanding the world, or frameworks, inform our ethical decisions, even if we are not fully aware of their influence. In this moment, many different narratives or frameworks are part of our public sphere, and they are often in contention. Furthermore, it is not always easy to figure out what to do in situations that present difficult ethical choices, even if we think we know, in general terms, the “right” thing to do. Whether it is a difficult choice that may result in an ethical lapse in business or politics or a disagreement about medical treatments and end-of-life decisions, people come into contact with ethical dilemmas regularly. Speakers and listeners of public speech face numerous ethical dilemmas as well. What kinds of support material and sources are ethical to use? How may speakers adapt to an audience and still maintain their own views? What makes a speech ethical?

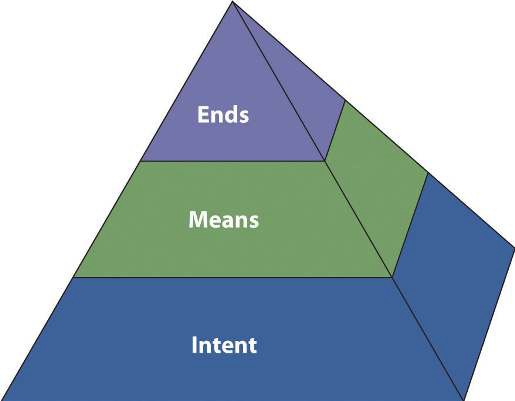

Figure 2.2 Ethical Pyramid

Image Long Description

This image is a three-dimensional pyramid diagram divided horizontally into three color-coded levels, each representing a different component of ethical decision-making in communication:

- Base (bottom layer, dark blue):

- Intent – the foundational level of the ethical pyramid, indicating that ethical communication begins with the speaker’s intent.

- Middle layer (green):

- Means – refers to the methods or processes used to achieve communication goals.

- Top layer (purple):

- Ends – represents the outcomes or results of communication actions.

The layered structure visually suggests that ethical communication builds upward, starting with intent, proceeding through means, and culminating in ends.

Text Transcription

Top: Ends

Middle: Means

Bottom: Intent

Try It: Sort the Ethics Pyramid

Activity Introduction: The Ethics Pyramid illustrates three guiding questions: What is my intent? What means am I using? What ends will my speech create? These questions are not abstract—they are the daily compass for ethical speaking.

Activity Instructions: In this activity, drag and drop these short scenarios into the three pyramid levels (Intent, Means, Ends).

Wrap-Up: The pyramid is not just a diagram—it’s a habit. Every time you prepare or deliver a speech, ask yourself: What is my intent? What are my means? What are my ends?

Intent

According to Tilley (2005), the first major consideration to be aware of when examining the ethicality of an action, whether spoken or performed, is the issue of intent. To be an ethical speaker or listener, it is important to begin with ethical intentions. For example, if we agree that honesty is ethical, it follows that ethical speakers will prepare their remarks with the intention of telling the truth to their audiences. Similarly, if we agree that it is ethical to listen with an open mind, it follows that ethical listeners will be intentional about letting a speaker make his or her case before forming judgments. Even in a time when “truth” is disputed (Neu, 2025), we still expect speakers to do their best to tell the truth, and we, as listeners, must work diligently to assess the truthfulness of speakers’ claims.

One option for assessing intent is to talk with others about how ethical they think a behavior is; if you get a fairly consistent set of answers saying the behavior is not ethical, then perhaps it should be avoided. A second option is to check out existing codes of ethics. Many professional organizations, including the Independent Computer Consultants Association, American Counseling Association, Society for Professional Journalists, Public Relations Society of American, and American Society of Home Inspectors, have codes of conduct or ethical guidelines for their members. Individual corporations such as Monsanto, Coca-Cola, Intel, and ConocoPhillips also have ethical guidelines for how their employees should interact with suppliers or clients. Even when specific ethical codes are not present, you can apply general ethical principles, such as whether a behavior is beneficial for the majority (utilitarianism) or whether you would approve of the same behavior if you were listening to a speech instead of giving it.

In addition, it is important to be aware that people can engage in unethical behavior unintentionally. For example, suppose we agree that it is unethical to take someone else’s words and pass them off as your own—a behavior known as plagiarism. What happens if a speaker makes a statement that he believes he thought of on his own, but the statement is actually quoted from a radio commentator whom he heard without clearly remembering doing so? The plagiarism was unintentional, but does that make it ethical?

Means

Tilley (2005) describes the means you use to communicate with others as the second level of the ethics pyramid. According to McCroskey, Wrench, and Richmond (2003), “means” are the tools or behaviors we employ to achieve a desired outcome. We must realize that there are a range of possible behavioral choices for any situation and that some choices are good, some are bad, and some fall in between.

For example, suppose you want your friend Marty to spend an hour reviewing a draft of your speech according to criteria, such as audience appropriateness, adequate research, strong support of assertions, and dynamic introduction and conclusion. What means might you use to persuade Marty to do you this favor? You might explain that you value Marty’s opinion and will gladly return the favor the next time Marty is preparing a speech (good means), or you might threaten to tell a professor that Marty cheated on a test (bad means). While both of these means may lead to the same end—having Marty agree to review your speech—one is clearly more ethical than the other.

The emergence of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) as a potential tool—or a means, in Tilley’s (2005) framework—for producing all or part of a speech calls for ethical discernment on the part of public speakers inside the classroom and beyond. Recent research on the ethical use of GenAI in public speaking suggests that it may supplement, supplant, assist, or coach in various parts of the speech construction and practice context (Pekka Isotalus & Karppinen, 2025; Pollino et al., 2025). Some issues emerging in the college classroom point to differences in opinion about the ethics of GenAI use (Tong et al., 2025). Should an instructor use AI to generate a syllabus? To create grading rubrics? To grade assignments? If public officials have speechwriters to craft their public messages, could they use AI instead? Keep in mind that even if you use AI for parts of your speech, you must still check the sources it suggests. Some programs generate false or biased information (Jungherr & Schroeder, 2023). There is no substitute for reviewing and checking the reliability of sources suggested by AI. Ethical public speaking requires verification of sources and information—attending to informational accuracy.

Your instructor will provide guidelines about the extent to which you are permitted to use GenAI in the process of constructing your speech. For instance, perhaps you are permitted to ask GenAI for possible speech topics, but you are to do your own research and create a speech outline and contents on your own. Some instructors may permit greater use of GenAI, as long as you provide the prompts you provided and show how you edited and reworked what GenAI supplied.

Ends

The final part of the ethics pyramid is the ends. According to McCroskey, Wrench, and Richmond (2003), ends are those outcomes that you desire to achieve. Examples of ends might include persuading your audience to make a financial contribution for your participation in Relay for Life, persuading a group of homeowners that your real estate agency would best meet their needs, or informing your fellow students about newly required university fees. Whereas the means are the behavioral choices we make, the ends are the results of those choices.

Like intentions and means, ends can be good or bad, or they can fall into a gray area where it is unclear just how ethical or unethical they are. For example, suppose a city council wants to balance the city’s annual budget. Balancing the budget may be a good end, assuming that the city has adequate tax revenues and areas of discretionary spending for nonessential services for the year in question. However, voters might argue that balancing the budget is a bad end if the city lacks these things for the year in question, because in that case balancing the budget would require raising taxes, curtailing essential city services, or both. Here, competing goods come into play, creating conflict (Arnett et al., 2018).

When examining ends, we need to think about both the source and the receiver of the message or behavior. Some end results could be good for the source but bad for the receiver, or vice versa. Suppose, for example, that Anita belongs to a club that is raffling off a course of dancing lessons. Anita sells Ben a ten-dollar raffle ticket. However, Ben later thinks it over and realizes that he has no desire to take dancing lessons and that if he should win the raffle, he will never take the lessons. Anita’s club has gained ten dollars—a good end—but Ben has lost ten dollars—a bad end. Again, the ethical standards you and your audience expect to be met will help in deciding whether a particular combination of speaker and audience ends is ethical.

Try It: Ethical Communication in Action

Activity Introduction: Public speaking involves constant ethical choices. Let’s test how ethical principles apply in real-world dilemmas.

Activity Instructions: Read each scenario and select the response that best aligns with ethical communication.

Wrap Up: Each scenario highlights how ethical lapses erode trust. By practicing integrity, clarity, and respect for audiences, speakers strengthen both their credibility and the health of democratic communication.

Thinking through the Pyramid

Ultimately, understanding ethics is a matter of balancing all three parts of the ethical pyramid: intent, means, and ends. When thinking about the ethics of a given behavior, you could ask yourself three basic questions:

- “Have I discussed the ethicality of the behavior with others and come to a general consensus that the behavior is ethical?”

- “Does the behavior adhere to known codes of ethics?”

- “Would I be happy if the outcomes of the behavior were reversed and applied to me?” (Tilley, 2005)

While you do not need to ask yourself these three questions before enacting every behavior as you go through a day, they do provide a useful framework for thinking through a behavior when you are not sure whether a given action or statement may be unethical. Ultimately, understanding ethics is a matter of balancing all three parts of the ethical pyramid: intent, means, and ends.

![]() Beyond the Podium Insight

Beyond the Podium Insight

Decision pyramids don’t just apply to speeches; they also help guide everyday workplace emails, political messages, and civic dialogue.

![]() AI Insight

AI Insight

Consider how using AI as a brainstorming tool, outline generator, or draft assistant affects your speech preparation. Does it change your intent? Are the means transparent? What ends might it create (for audience trust, authenticity, or credibility)?

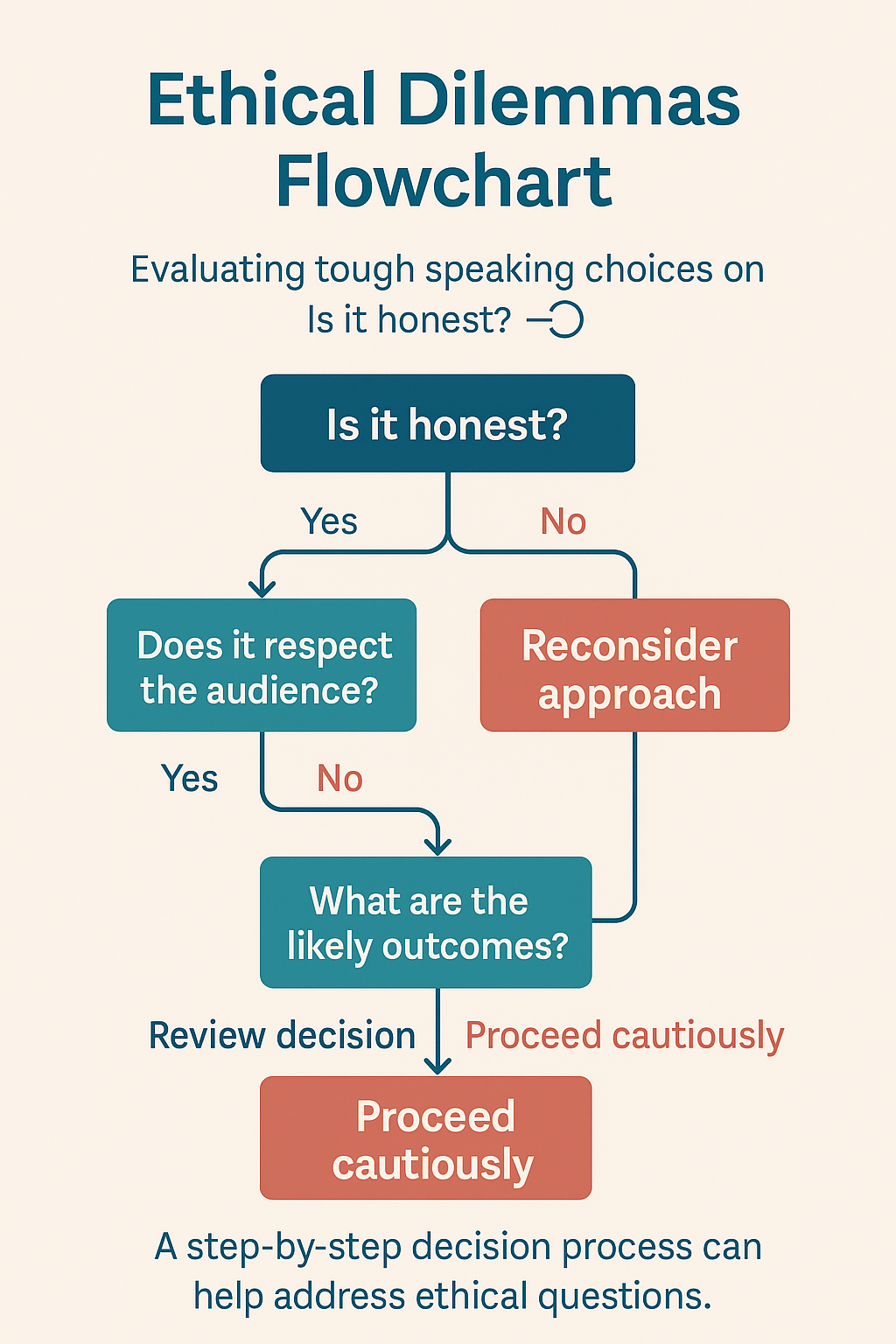

Figure 2.3 Thinking Through the Pyramid

Image Long Description

This infographic is titled “Ethical Dilemmas Flowchart” and provides a step-by-step visual decision tree to help speakers evaluate ethical choices.

Title: Ethical Dilemmas Flowchart

Subtitle: Evaluating tough speaking choices on: Is it honest?

The flowchart starts at the top with the question:

- Is it honest? (blue box)

→ If No → Reconsider approach (red box)

→ If Yes → continue to next question: - Does it respect the audience? (blue box)

→ If No → proceed to:

→ If Yes → proceed to: - What are the likely outcomes? (blue box)

→ If the outcomes raise concerns → Proceed cautiously (red box)

→ If appropriate → Review decision, then → Proceed cautiously (red box)

At the bottom, the image concludes with a note:

“A step-by-step decision process can help address ethical questions.”

The layout and color-coding (blue for questions and red for warnings) guide readers toward careful, ethical communication decisions.

Text Transcription

Ethical Dilemmas Flowchart

Evaluating tough speaking choices on: Is it honest?

[Is it honest?]

- → Yes → [Does it respect the audience?]

- → Yes → [What are the likely outcomes?]

- → Review decision → [Proceed cautiously]

- → or → Proceed cautiously → [Proceed cautiously]

- → No → [What are the likely outcomes?] → Proceed cautiously

- → No → [Reconsider approach]

A step-by-step decision process can help address ethical questions.

Try It: Case Study: AI-Generated Content and Ethical Dilemmas

Activity Introduction: We have seen how the ethics pyramid helps us analyze intent, means, and ends in traditional speaking situations. But what happens when artificial intelligence is added into the mix? AI tools can generate speech content quickly, yet they also raise new ethical dilemmas, especially when accuracy, bias, and authenticity are at stake. The following activity invites you to apply the pyramid directly to an AI-generated case.

Activity Instructions: Click on each card to view how Intent, Means, and Ends change depending on how AI is used.

Wrap Up: Which choice best aligns with ethical speaking practices? How do intent, means, and ends guide your decision?

These cards highlight that using AI in speech preparation is not just a matter of efficiency—it is an ethical choice. Whether you decide to use, revise, or discard AI-generated content, your decision shapes audience trust and your credibility as a speaker. By examining intent, means, and ends, you can ensure that AI remains a tool that supports responsible communication rather than undermining it.

Free Speech, the First Amendment, and AI Responsibility

When considering free speech in the context of AI-generated communication, it is important to distinguish between the legal protections of the First Amendment and the ethical responsibilities of speakers. The First Amendment limits government restriction of speech but does not extend absolute protection to all forms of expression—speech that is obscene, defamatory, or incites violence may be restricted.

AI complicates this landscape by introducing a layer of authorship that is not human. If an AI tool generates harmful, misleading, or offensive content, the question arises: who bears responsibility—the tool’s developer, the platform that hosts the content, or the human speaker who used the tool? From an ethical standpoint, the speaker remains accountable for what is delivered in their name, even if the words originated from an algorithm.

This means that while AI can serve as a helpful partner in drafting or shaping ideas, speakers must evaluate the content through the lens of both legal principles and ethical responsibility. In practice, this requires fact-checking AI outputs, considering potential harm, and recognizing that the use of AI does not absolve a speaker of accountability for the outcomes produced.