4.4: Why Listening IS Difficult

Janie Harden Fritz

Learning Objectives

- Understand the types of noise that can affect a listener’s ability to attend to a message.

- Evaluate how AI-generated information, including content curation and algorithmic recommendations, contributes to different types of noise that impact a listener’s ability to process a message.

- Explain how a listener’s attention span can limit the listener’s ability to attend to a speaker’s message. Analyze how a listener’s personal biases can influence her or his ability to attend to a message.

- Define receiver apprehension and the impact it can have on a listener’s ability to attend to a message.

At times, everyone has difficulty staying completely focused during a lengthy presentation. We can sometimes have difficulty listening to even relatively brief messages. Some of the factors that interfere with good listening might exist beyond our control, but others are manageable. It’s helpful to be aware of these factors so that they interfere as little as possible with understanding the message.

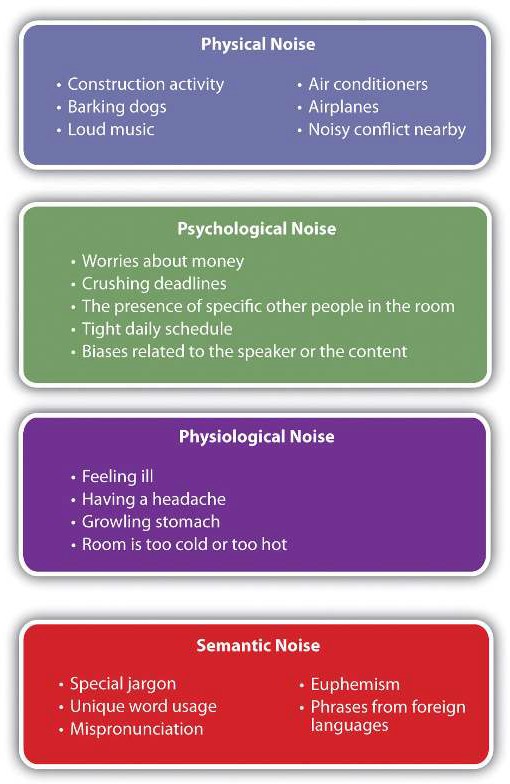

Figure 4.4: Types of Noise

Image Long Description

This image categorizes four types of communication noise into colored boxes, each listing common examples:

Physical Noise (blue box):

- Construction activity

- Barking dogs

- Loud music

- Air conditioners

- Airplanes

- Noisy conflict nearby

This category includes external environmental sounds that interfere with hearing a message.

Psychological Noise (green box):

- Worries about money

- Crushing deadlines

- The presence of specific other people in the room

- Tight daily schedule

- Biases related to the speaker or the content

These are internal distractions that affect how a message is received or interpreted.

Physiological Noise (purple box):

- Feeling ill

- Having a headache

- Growling stomach

- Room is too cold or too hot

This noise stems from bodily discomfort or health conditions that hinder effective communication.

Semantic Noise (red box):

- Special jargon

- Unique word usage

- Mispronunciation

- Euphemism

- Phrases from foreign languages

This refers to language-based barriers that prevent the message from being understood.

Text Transcription

Physical Noise:

- Construction activity

- Barking dogs

- Loud music

- Air conditioners

- Airplanes

- Noisy conflict nearby

Psychological Noise:

- Worries about money

- Crushing deadlines

- The presence of specific other people in the room

- Tight daily schedule

- Biases related to the speaker or the content

Physiological Noise:

- Feeling ill

- Having a headache

- Growling stomach

- Room is too cold or too hot

Semantic Noise:

- Special jargon

- Unique word usage

- Mispronunciation

- Euphemism

- Phrases from foreign languages

Physical noise emerges from the environment, the place where the speech is taking place. Some physical noise can be avoided if speakers are able to plan in advance—for instance, a space closer to the interior of a building may be available if construction is taking place outside. If unplanned and unavoidable noise happens during a speech, speakers may respond creatively by moving away from the front of the room to be closer to the audience. What other alternatives can you think of to respond to unexpected noise?

Psychological noise on the part of audience members is harder to control, but with a lively and compelling presentation style, speakers may invite more attentive listening even on the part of listeners whose minds are elsewhere, either on the meal that will take place after a speech or personal concerns that pull attention away from the speaker. Likewise physiological noise related to one’s bodily reactions to the environment (the room is too hot or too cold for an audience member) or due to illness may be beyond a speaker’s control.

Speakers can avoid creating semantic noise, which emerges from vocabulary that is likely to be unfamiliar to an audience if the speaker hails from a specialized profession, by crafting a speech that incorporates everyday understandings of complex terms or translates phrases in a language other than of the audience members.

Many distractions are the fault of neither the listener nor the speaker. However, when we are speakers, being aware of these sources of noise can help us reduce interferences with our audience’s ability to understand.

Information generated through AI, because of the way AI is is trained through large language models (LLMs,) work, is subject to biases emerging from the data available learning. Biases emerging from human error and assumptions are part of the data available for algorithmic training of AI systems. Biases are passed on through data gathering, shaping AI output according to the content curation practices of countless (typically unknowing) providers of material for AI learning (Williams & Prybutok, 2024). Errors that emerge in this fashion and that appear when AI is used can be considered a type of noise that affect the accuracy of messages. If public speakers do not attend to the accuracy of AI-generated information, listeners will receive inaccurate information.

Try It: Algorithmic Noise Challenge

Activity Instructions: Identify the type of noise each situation represents.

Wrap Up: Noise isn’t just about loud sounds — it can come from algorithms, biases, and the way technology filters information. By learning to recognize algorithmic noise, you are practicing both listening awareness and AI literacy.

Being able to separate meaningful messages from digital distractions will help you listen more critically, both in class and in everyday life.

Attention Span

A person can only maintain focused attention for a finite length of time. In his 1985 book Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business, New York University’s Steinhardt School of Education professor Neil Postman argued that contemporary audiences have lost the ability to sustain attention to a message (Postman, 1985). More recently, researchers have engaged in an ongoing debate over whether Internet use is detrimental to attention span (Carr, 2010).

The limits of the human attention span can interfere with listening, but listeners and speakers can use strategies to prevent this interference. As many classroom instructors know, listeners will readily renew their attention when the presentation includes frequent breaks in pacing (Middendorf & Kalish, 1996). For example, a fifty- to seventy-five-minute class session might include some lecture material alternated with questions for class discussion, video clips, handouts, and demonstrations. Instructors who are adept at holding listeners’ attention also move about the front of the room, write on the board, draw diagrams, and intermittently use PowerPoint slides or videos.

Receiver Biases

Good listening involves keeping an open mind and withholding judgment until the speaker has completed the message. Conversely, biased listening is characterized by jumping to conclusions; the biased listener believes, “I don’t need to listen because I already know what I think.” Receiver biases can refer to two things: biases with reference to the speaker and preconceived ideas and opinions about the topic or message. Both can be considered noise. Everyone has biases, but good listeners have learned to hold them in check while listening.

The first type of bias listeners can have is related to the speaker. Often a speaker stands up and an audience member simply doesn’t like the speaker, so the audience member may not listen to the speaker’s message. Maybe the speaker is an annoying classmate, or maybe we question a classmate’s competence on a given topic. When we have preconceived notions about a speaker, those biases can interfere with our ability to listen attentively to the speaker’s message, decreasing our listening accuracy.

The second type of bias listeners can have is related to the topic or content of the speech. If the speech topic is one we’ve heard a thousand times, then we might tune out. Or maybe the speaker is presenting a topic or position we fundamentally disagree with. When listeners have strong preexisting opinions about a topic, such as the death penalty, religious issues, abortion, or climate change, their biases may make it difficult for them even to consider new information about the topic, especially if the new information is inconsistent with what they already believe to be true. On the other hand, if we are listening to speaker whose views are in alignment with our own, we may fail to listen as critically as we might, which is another type of bias. As listeners, we have difficulty identifying our biases, especially when they seem to make sense. However, it is worth recognizing that our lives would be very difficult if no one ever considered new points of view or new information. We live in a world where everyone can benefit from clear thinking and open-minded listening.

Listening or Receiver Apprehension

Listening or receiver apprehension is the fear that we might be unable to understand the message or process the information correctly or be able to adapt our thinking to include the new information coherently (Wheeless, 1975). In some situations, we might worry that the information presented will be “over our heads”—too complex, technical, or advanced for us to understand adequately.

Many students will actually avoid registering for courses in which they feel certain they will do poorly. In other cases, students will choose to take a challenging course only if it’s a requirement. This avoidance might be understandable but is not a good strategy for success. To become educated people, students should take a few courses that can shed light on areas where their knowledge is limited.

As speakers, we can reduce listener apprehension by defining terms clearly and using simple visual aids to hold the audience’s attention. We don’t want to underestimate or overestimate our audience’s knowledge on a subject, so good audience analysis is always important. For example, if we know our audience doesn’t have special knowledge on a given topic, we should start by defining important terms. Research has shown us that when listeners do not feel they understand a speaker’s message, their apprehension about receiving the message escalates. Imagine that we are listening to a speech about chemistry and the speaker begins talking about “colligative properties.” We may start questioning whether we are even in the right place. When this happens, apprehension clearly interferes with a listener’s ability to understand a speaker’s message accurately and competently. As a speaker, we can lessen the listener’s apprehension by explaining that colligative properties focus on how much is dissolved in a solution, not on what is dissolved in a solution. We could also give an example that they might readily understand, such as saying that it doesn’t matter what kind of salt to use in the winter to melt ice on a driveway—what is important is how much salt to use.