6.2 Developing a Research Strategy

Terri Stiles

Learning Objectives

- Differentiate between research time and speech preparation time.

- Understand how to establish research needs before beginning research.

- Explain the difference between academic and nonacademic sources.

- Identify appropriate nonacademic sources (e.g., books, special-interest periodicals, newspapers and blogs, and websites).

- Identify appropriate academic sources (e.g., scholarly books, scholarly articles, computerized databases, and scholarly information on the web).

- Evaluate George’s (2008) six questions to analyze sources.

- Identify potential biases and limitations in AI-generated research sources.

- Assess the credibility of AI-generated sources and integrate them ethically.

Research Strategy

In the previous section we discussed what research is and the difference between primary and secondary sources. In this section, we are going to explore how to develop a research strategy. Think of a research strategy as your personal map. The end destination is the actual speech, and along the way, there are various steps you need to complete to reach your destination: the speech. From the day you receive your speech assignment, the more clearly you map out the steps you need to take leading up to the date when you will give the speech, the easier your speech development process will be (Tajvidi, 2015). In the rest of this section, we are going to discuss time management, determining your research needs, finding your sources, and evaluating your sources.

Allotting Time

When starting any new project, big or small, a critical first step is to accurately estimate the time commitment. This is especially true for tasks like speech preparation, where deadlines are often set. Let’s break down the process using a project life cycle approach, adapted for your academic reality. The moment your instructor assigns a speech; the clock starts ticking. Every day without progress is a day of lost opportunity for a polished presentation. We get it — college life is packed with classes, family, jobs, friends, and social engagements. That’s why smart time management for both research and speech development is so important. (Patzak, 2025); (Project Management Institute, 2024); (Wolters and Brady, 2021)

Research Time

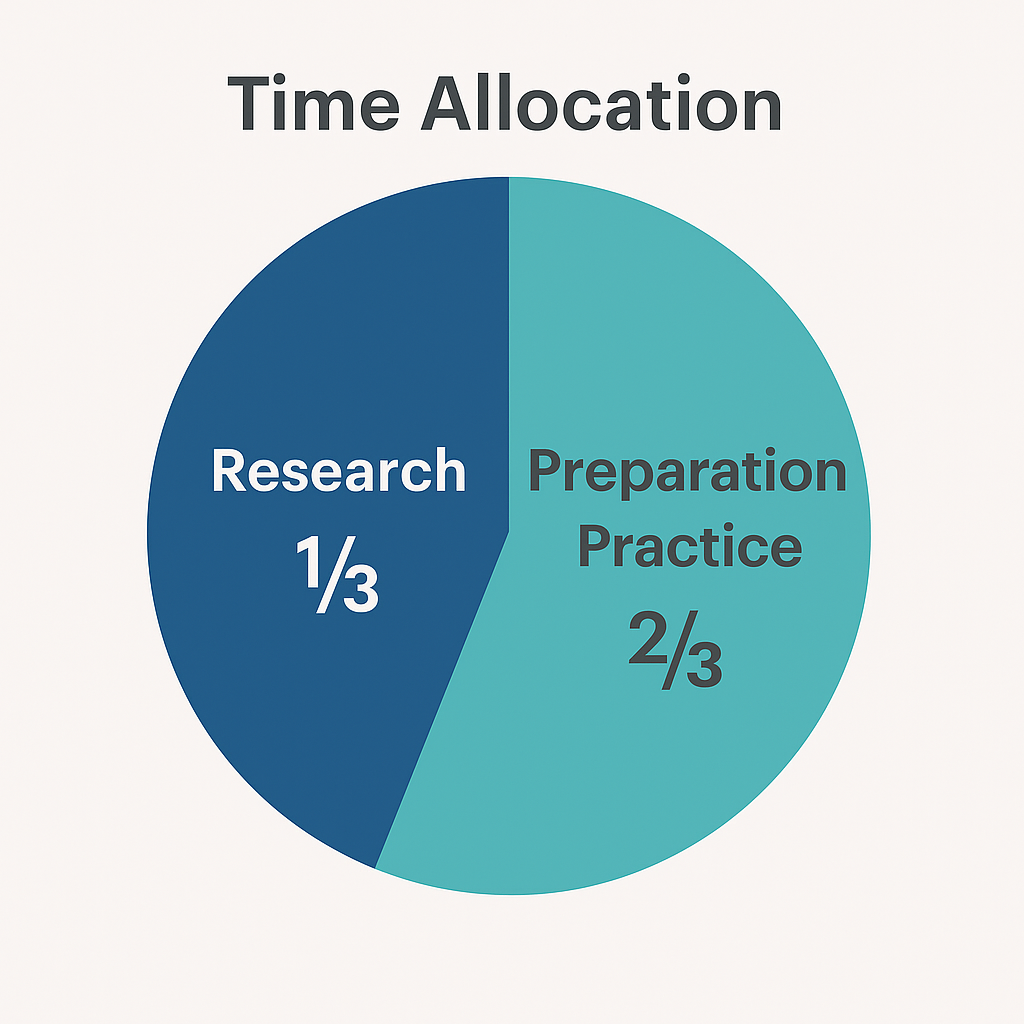

Research often consumes a significant portion of your preparation. Whether you’re gathering primary data or relying on secondary sources, expect to dedicate ample time to this phase. Think of research as an iterative process, not a one-and-done task. As your speech evolves, you might uncover new questions or realize you need additional information to strengthen the point. Always allow some buffer time for follow-up research. Don’t forget about research librarians! They’re invaluable resources with tips and tricks to streamline your search. However, librarians have busy schedules, so proactively book an appointment once you have your initial questions mapped out. A good rule of thumb is to dedicate no more than one-third of your total speech preparation time to research. For example, if you have three weeks, aim to wrap up your research by the end of the first week. Neglecting this balance can lead to a last-minute scramble to write your speech, which is highly inadvisable. (Browne, 2013; Landry et al., 2024)

Try It: Plan Your Research and Speech Schedule

Wrap-up: Time management transforms stress into structure. The sooner you plan, the more confident your final presentation will feel.

Speech Preparation Time

The second major phase is crafting your speech. This is where you transform your research into a cohesive and compelling presentation. You’ll be building arguments, integrating evidence, and potentially designing visual aids. Give yourself sufficient time for this crucial stage. A common guideline is to allocate one day of preparation for every minute of speaking time. Being sure to build in a time buffer also provides a safety net for unexpected life events. Things happen, and unforeseen circumstances can derail your progress. Having extra preparation time protects you from these disruptions and ensures you can still deliver a high-quality speech. Finally, there’s practice. This means actively rehearsing your speech aloud. Simply scripting or mentally reviewing your speech isn’t enough. Research shows that speakers who practice orally are more aligned with their intended delivery when presenting. This dedicated practice time helps you become comfortable not only with your speech’s content but also with your nonverbal delivery. (Hartelius, 2018)

Determining Your Needs

Before diving into research, define your objectives. Start by clarifying your topic and considering any specific guidelines from your instructor. Once you have a general understanding, ask yourself these questions: What do I already know about this topic? Are there any significant gaps in my current knowledge or in literature? Do I need to conduct primary research (e.g., interviews, surveys)? What type of secondary research is required (facts, theories, applications)? The clearer you are about your research needs upfront, the more efficient your information gathering will be. (Browne, 2013)

Figure 6.2: Speech Preparation Time

Image Description

The image contains a circular pie chart titled “Time Allocation.” The chart is split into two unequal sections:

- The left third of the circle is dark blue and labeled:

- “Research”

- “1/3”

- The right two-thirds of the circle is teal and labeled:

- “Preparation Practice”

- “2/3”

This visual emphasizes that while research is essential, the majority of time should be spent practicing and preparing the delivery of a speech or presentation.

Text Transcription

Time Allocation

Research

1/3

Preparation

Practice

2/3

University and College Libraries

University and College Libraries are incredible sources of academic resources. Most Universities and college libraries today offer physical libraries, hybrid libraries, and online libraries. The University or college library is the best place to begin your research.

- Physical Libraries: Visiting the library can be a great way to discover resources you might miss online. Most follow the Library of Congress system, making navigation familiar across different institutions. Browsing shelves can also lead to unexpected discoveries. (Hider, et al.2022)

- Hybrid Libraries (Physical & Electronic): Most college and university libraries offer both physical collections and extensive electronic databases. Major e-book providers like ebrary and NetLibrary house vast digital collections. Additionally, many prestigious institutions like Harvard, the New York Public Library, the British Library, and the U.S. Library of Congress offer portions of their collections online for free. (Arulmathi and Kannan, 2019)

- Online-Only Libraries: The digital age has brought a surge of purely online libraries offering free, full-text documents. Notable examples include Project Gutenberg, Google Books, Read Print, Open Library, and Get Free E-Books. (Akhtar, 2020)

Library Resources for Research:

Academic Information Sources

Academic sources, also known as scholarly sources, are publications that contain research-based information written and reviewed by experts in a specific field. They include journal articles, books, conference proceedings, theses, dissertations, and academic databases. These sources are typically peer-reviewed, meaning they have been evaluated by other experts to ensure accuracy and quality. Collections are generally housed in databases and be easily searched on your institution’s library web page.

- Textbooks: Written for student audiences, these books survey existing research within a specific academic field (e.g., a public speaking textbook). They are secondary sources designed for information transfer. Many colleges and universities are moving towards open-source textbooks for their courses. (Kotsiou and Shores, 2021)

- Academic Books: Books delve deeper into research and often present new findings. Major publishers include SAGE, Routledge, Jossey-Bass, and various university presses (e.g., Oxford University Press, University of Illinois Press).

- Journal Articles: Published in scholarly journals, they often feature original research and are peer-reviewed. Journal articles are usually based on academic studies or literature reviews. (Arrom, et al., 2018)

- Conference Papers: Papers presented at academic conferences often explore cutting-edge research in dynamic fields. Conferences include talks, poster sessions, and workshops.

- Government Publications: Reliable data and information related to policy and government initiatives. They are published by Federal, State and Local governments. The Occupational Outlook Handbook is an example that gives up to date information about career choices. (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2025)

- Theses/Dissertations: A thesis is the final research project that students do in their master’s program. A Dissertation is the final research project that students do in their Doctoral programs. These are usually published in academic journals and in the library of their graduate school. (Lovitts and Wert, 2009)

- Academic Databases: Collections of scholarly materials, often accessed through university libraries or subscription services. A list of popularly used databases is below.

- Research Reports: Insights from think tanks and organizations, providing detailed analyses and recommendations. The university of Pennsylvania has a list of the major public policy think tanks in the United States: https://guides.library.upenn.edu/c.php?g=1035991&p=7509974

- Encyclopedias: Broad overviews of topics, offering background information and definitions.

- Dictionaries: Provide definitions and explanations of terms.

- Websites: Some educational websites and academic databases offer valuable supplemental information.

- Online Archives: Historical documents and early research.

- AI Tools: Can help with searches, brainstorming and polishing but should never be used to replace your writing style or speaking voice.

General Academic Search Engines & Databases:

General: Google Scholar, JSTOR, Scopus, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, BASE, CORE, Semantic Scholar.

Subject-Specific: PubMed/PMC (Medicine), ERIC (Education), IEEE Xplore (Engineering), arXiv (Pre-prints), SSRN (Social Sciences).

Open Access & Free: DOAJ, Science.gov, Un paywall, OATD, Digital Commons Network.

Other: ResearchGate, Google Books, Library of Congress.

Other Valuable Resources:

- ResearchGate: A social networking site for scientists and researchers where they can share papers, ask questions, and find collaborators. It also provides access to many open-access articles.

- Google Books: A vast database of scanned books and magazines, useful for finding books that contain specific search terms, even if you don’t have full-text access.

- Library of Congress (LOC): The largest library in the world, offering a massive collection of books, recordings, photographs, newspapers, maps, and manuscripts.

- When conducting scholarly research, it’s often best to utilize a combination of these resources, especially those provided by your university or institution, as they often offer full access to subscription-based databases. Your librarians can help guide you as to which databases will be the best for the project you are undertaking. Since new databases may be added anytime, it is best to check with your institution’s Library. You can view Penn State’s list of current academic data bases on the Penn State University Libraries Website.

Key Characteristics to help you recognize Academic Writing.

- The Author has written other works in the field and is associated with a university or research group.

- The Publisher has published other works in the field.

- The citations are scholarly

- The book or article has been edited and peer reviewed.

- Be sure you are on a .edu or teacher approved .gov or .org.

Nonacademic Information Sources

Non-academic information sources, also known as popular sources or non-scholarly sources, are designed for a general audience rather than a specialized, academic one. They often aim to inform, entertain, or persuade, and typically do not undergo the rigorous peer-review process that scholarly sources do. Here are common types of non-academic information sources. These sources can be a good starting point for background information about your topic.

- Newspapers: Provide current events, news, and often opinion pieces. Examples include The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and local newspapers. While they offer valuable timely information, their primary purpose isn’t in-depth academic research, and they may not always cite sources in detail. Local newspapers (printed or online) can provide details about local events that the larger papers may not cover. (Sagic, 2019)

- Magazines: These can range from general interest (Time, Newsweek) to special interest (National Geographic, Scientific American, Psychology Today) or entertainment (People, Rolling Stone). They are written for a broad readership, often feature more casual language, and typically include many images and advertisements. (Rizvi &Hussian, 2023)

- Trade Journals/Publications: While more specialized than general magazines, these are still considered non-academic. They target professionals within a specific industry or field (e.g., Advertising Age, Chronicle of Higher Education). They provide industry news, trends, and practical applications, but generally don’t present original, peer-reviewed research. Silva et al. (2024) found that trade publications and journals provide a bridge between readers and prior research.

- Websites: This is a vast category. Many websites, including personal blogs, commercial sites, news sites (not formal news publications), and opinion-based platforms, fall under non-academic. While some can offer valuable information, their credibility varies widely, and it’s crucial to evaluate them carefully for bias, accuracy, and currency. Similar to Trade Journals, these sites can lead readers to more academic articles. (Obionwu, Broneske, Saake, 2022)

- Social Media: Platforms like (X), Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok are primarily for communication, entertainment, and sharing opinions. They are generally not considered reliable sources for academic research due to their informal nature, lack of vetting, and potential for misinformation. (Denniss and Lindberg, 2025)

- Reference Works (general): While useful for general knowledge, sources like Wikipedia and general encyclopedias are often considered non-academic. They are good starting points for understanding a topic, but because they can be edited by anyone and are not peer-reviewed, they should not be cited as primary academic sources. In some Wikipedia articles there are academic articles listed at the bottom of the Wikipedia article that can get students started on their research. (Wikipedia)

- Documentaries and Films: While they can offer insights and perspectives, documentaries and films are often created for entertainment or to promote a specific viewpoint and may not adhere to the same rigorous standards of evidence and objectivity required for academic work. They can often provide additional understanding of the topic you are studying. (Ghambi, et. al. 2023)

Key Characteristics to help recognize Non-Academic Sources

- Audience: General public.

- Purpose: Inform, entertain, persuade, or sell.

- Authorship: Often journalists, freelance writers, or staff writers; credentials may not be listed or extensive.

- Language: Casual, informal, may include slang.

- Review Process: Edited by staff editors, not typically peer-reviewed by experts in the field.

- Citations/References: Rarely include formal citations, footnotes, or bibliographies.

- Appearance: Often visually appealing, with graphics, photographs, and advertisements.

- Frequency of Publication: Can be daily, weekly, or monthly

- Non-Academic sources can help students gain an initial understanding of a topic by gathering information. They can also find current events and public opinion.

- (Mayer and Minervini, 2023)

Reading Literacy Skills for Students to Use When Reading Research Articles

Once you have chosen a research article, the first thing you can do is read the Abstract. This will give you a brief overview of the article. Next, read the conclusion section to see what the study found. Finally, go back and read the whole article so that you can summarize it in your paper or speech.

Here are some ways to practice literacy as you are reading:

- Look for the main idea of the article.

- Take notes of ideas in the article that back up this idea.

- Consider the point of view of the writer and double check for biases.

- Review any charts and graphs and make sure you understand their meaning.

- Check the bibliography, works cited, or reference list to see what articles the author cited that you may want to use.

- Next, find other articles on the same topic and see if they are saying the same thing.

Ask for Help

- Don’t be afraid to ask for help. As discussed earlier in this chapter, reference librarians are your friends. They won’t do your work for you, but they are more than willing to help if you ask.

Biases and Limitations of AI-Generated Research Sources

AI-generated research sources, such as information from chatbots, offer advantages in speed and accessibility, but are also susceptible to various biases and limitations that can compromise their reliability and validity. These challenges arise from the data on which AI models are trained and the design of algorithms themselves. You do not want to repeat any AI biases when presenting your speech. For these reasons, it is crucial to double-check the validity of any information obtained through AI research.

Key Sources of Bias

1. Data Bias

AI models learn from vast datasets created by humans. If these datasets reflect societal biases—such as those based on gender, race, culture, or socioeconomic status—the AI will likely reproduce and potentially amplify them.

Here are some examples:

- An AI trained predominantly in research authored in Western contexts may overrepresent Western perspectives while underrepresenting or misinterpreting non-Western viewpoints. This became evident in a study by Xu (2025), which found that language models favored Western ideas and viewpoints even when alternative viewpoints were offered.

- A medical research model trained primarily on data from a specific demographic may produce findings that are not generalizable across diverse populations. Mittermaier, Raza, and Kvedar (2023) found that care decisions were biased against people from non-Western cultures.

- Zinnya del Villar (2025) discussed, in a U.N. forum, how AI language models trained on internet data may perpetuate gender stereotypes, such as associating certain professions (e.g., nurse, engineer) with specific genders. She emphasizes, however, that AI can also be trained to be more inclusive.

2. Algorithmic Bias

Biased feature selection, variable weighting, and optimization goals can introduce biases into AI models. These processes can inadvertently favor certain outcomes or groups over others, leading to unfair or inaccurate results. This is especially seen in the human resource field. Chen (2023) explains that biases exist in algorithms based on who created the algorithm, considering gender, race, color, and personality traits.

3. Implicit Bias

The optimization process itself can reflect assumptions or biases of the developers, leading to models that favor specific outcomes. Marinucci, Mazzuca, and Gangemi (2023) discovered that race and gender biases exist in many AI systems. For example, they indicated that when an AI was asked to show a picture of a woman, it consistently showed a white woman, which revealed the biases and stereotypes the AI system had when retrieving the picture.

4. Confirmation Bias

The way a prompt is framed can lead an AI to prioritize information that confirms a user’s assumptions while ignoring contradictory evidence. This unintentional reinforcement of pre-existing beliefs may lead to biased conclusions. Bashkirova and Krpan (2024) discussed how psychologists favor AI recommendations that match their initial diagnosis, making them more likely to accept future AI suggestions.

5. Measurement Bias

Errors in the way data is processed or interpreted can lead the model to learn and reproduce those biases. Hasanzadeh et al. (2025) delineated a problem when medical information is gathered from many different hospitals, each with different data collection methods. They report that this happened with medical diagnostic hardware purchased from varied manufacturers.

Additional Considerations Contributing to Bias:

1. Feature Selection

- Biased Feature Selection: If the chosen features do not adequately represent the underlying problem or are not equally relevant across all subpopulations, the model can be biased. For example, a COVID-19 risk prediction model might underrepresent social determinants of health like socioeconomic status, leading to biased outcomes for vulnerable populations (Brakefield et al., 2022).

- Inadequate Representation: Features might be selected that are primarily available for the majority group, leading to a “one-size-fits-all” approach that doesn’t account for the unique characteristics of subgroups (Holm & Ploug, 2023).

- Aggregation Bias: Data aggregation, where data from different sources is combined, can introduce bias through the selection of features that are maximally available across all subjects, leading to a “one-size-fits-all” approach (Nazer et al., 2023).

2. Variable Weighting

- Differential Weighting: If certain features are given disproportionate weight, the model can be biased towards those features, potentially ignoring or downplaying other important factors (Swartz et al., 2022).

- Ignoring Interactions: Some feature selection techniques may not adequately model feature-feature interactions, potentially leading to the loss of relevant interacting features (Pudjihartono et al., 2022).

3. Optimization Goals

- Favoring Specific Outcomes: The optimization goal of a model can unintentionally favor certain outcomes or groups. For example, a model trained to predict recidivism might unintentionally discriminate against certain racial groups (Belenguer, 2022).

4. Hallucinations and Factual Inaccuracies

AI models can generate confident but incorrect or entirely fabricated information, often referred to as “hallucinations.” According to IBM (2025), common issues can include fabricated citations or non-existent sources, invented statistics or research findings not supported by evidence, and misrepresentation of existing research.

5. Lack of Nuance and Contextual Understanding

AI often struggles with complex reasoning and may fail to grasp nuance, leading to oversimplification, omission of alternate interpretations, and/or superficial summaries lacking critical analysis. Thakkar et al. (2024) offer an example of AI assuming a behavior is a mental disorder when it is a cultural norm.

6. Reproducibility Issues

The outputs of AI models can vary depending on phrasing, version, or even the same input given at different times. This non-determinism can challenge reproducibility, which is vital in rigorous academic work. In other words, how can AI be cited if the cited data is constantly changing? The University of Maryland (2025) explains that AI needs to be cited as any other citation using standard formats.

7. Attribution and Plagiarism Concerns

AI-generated text may synthesize information from various sources without clear attribution. Without proper user review and citation, this poses a risk of unintentional plagiarism and ethical issues surrounding authorship (Chan, 2025).

AI Mitigation

Ferrara (2024) studied AI mitigation strategies and found that data diversity, feature selection techniques, fairness metrics, and bias detection and mitigation tools can help ensure the inclusion of all possible participants. They suggested implementing transparent AI training data. Elkhatat et al. (2023) discussed evaluating AI sources, recommending verifying information, watching out for hallucinations, assessing the logic and coherence, and being aware of biases. They recommend researching the information AI provides to find out the source that AI uses.

Assessing the Credibility of AI-Generated Sources

As you are researching sources for your speech, please be aware that AI tools, especially large language models (LLMs), can “hallucinate” information, meaning they produce factual errors, invent sources, or present biased or incomplete data. As such, critical evaluation is extremely important when using them.

1. Fact-Checking and Verification:

- Cross-Reference with Reputable Sources: The most important step is to verify any factual claims made by AI with multiple, established, and credible sources. This includes academic journals, government publications, reputable news organizations, and well-regarded library databases. Giray (2023) found that ChatGPT tended to create citations that were not real or that pointed to non-academic sources.

- “Lateral Reading”: After searching on AI, open new tabs and search for the claims made by the AI. This involves investigating the source of the information and looking for supporting or contradictory evidence from other sources. Zhang and Pradeep (2023) explain ReadProbe, a tool that performs lateral reading on chosen citations. Of course, performing your own lateral reading will help you avoid possible AI biases and hallucinations. (Readprobe open code, n.d.)

- Verify Citations (if provided): AI tools may provide citations, but these can be fake or inaccurate. Always look up the cited articles, books, or websites to ensure they exist and actually support the claims made by the AI. Check author names, publication titles, dates, and page numbers. Then, determine if they are academic resources. Caon et al. (2020) illustrate how the quality of citations usually reflects the quality of the paper, a worthwhile idea to remember.

- Compare with Other AI Tools: Try giving the same prompt to different AI tools and compare the results. Discrepancies can signal a need for further investigation. A caution, however, is presented by Sonmezoglu and Sonmezoglu (2024), who tested ChatGPT, Google Gemini, and Copilot with a prompt regarding cataract eye surgery and found serious quality issues in all three systems.

2. Identifying Bias and Missing Information:

- Consider the Training Data: AI models are trained on vast datasets, which can inherently contain biases or be outdated. Recognize that AI reflects the biases present in its training data and may not present a neutral or comprehensive perspective. In 2022, the EU released AI regulations that require AI to be transparent and non-discriminatory (“EU AI Act,” n.d.). Liang (2022) found that the way data is developed and presented can have a huge effect on the efficacy and fairness of the model. They suggest evaluation and annotation at every stage of development, which will also make the models more transparent.

- Look for Multiple Perspectives: Does the AI content present a balanced view, or does it seem to favor a specific viewpoint, ideology, or group? Be wary of content that omits important information or promotes stereotypes. Matusov et al. (2024) have shown that AI does not have a dialogical self but rather a recursive self, one that can just follow the instructions of the prompt. It is up to the user to request that the AI look at an issue from multiple viewpoints.

- Assess for Oversimplification: Metcalfe et al. (2021) state that systems can sometimes oversimplify complex issues, missing nuances, interconnectedness, or wider context. Always delve deeper into topics presented by AI to ensure you understand their full potential.

- Check for Emotional or Manipulative Language: Credible sources typically use neutral, fact-based language. Be cautious of AI-generated content that uses overly dramatic, inflammatory, or emotionally charged language designed to provoke a reaction or influence opinions. Monteith et al. (2022) warn that there is a growing use of AI for commercial purposes, so the AI may be collecting data on you and leading your search to a commercial end rather than an academic one.

Try It: AI Bias Detective

Wrap up: Recognizing bias in AI-generated language helps you maintain fairness, inclusivity, and credibility in your speeches. Ethical communicators ensure their messages reflect diverse perspectives.

3. Evaluating Authority and Currency:

-

No Human Author: Remember that AI-generated text has no human author and cannot “think” like a person. While it can mimic human writing, it lacks the critical thinking, nuanced understanding, and ethical reasoning of a human being. Khemlani and Johnson-Laird (2019) explain that humans can understand inference and react to it by generating possibilities, whereas AI can only evaluate existing possibilities.

- Check for Timeliness: AI’s training data might not be up-to-the-minute. Confirm the publication date of any source material the AI has cited. For rapidly evolving topics, AI’s information might be outdated. In a study on AI use in scientific writing, Kacena et al. (2024) realized that ChatGPT 4.0 had a cutoff date of September 2021. Because of this, ChatGPT couldn’t recognize articles published after that date.

Try It: Identifying Reliable AI Research Sources

Wrap-Up: Effective communicators verify every piece of AI-generated content before using it. This exercise reinforces the importance of checking accuracy, identifying bias, and ensuring credibility in your research.