8.1: The Six Functions of an Effective Introduction

Tiffany Petricini

Learning Objectives

- List and describe the six essential functions of an effective speech introduction: attention, relevance, thesis, credibility, preview, and tone.

- Explain the purpose of each function and how it contributes to audience engagement and message clarity.

- Identify examples of effective and ineffective introduction elements using real-world or classroom speech contexts.

- Describe the components of speaker credibility (competence, trustworthiness, and goodwill) and apply strategies for establishing credibility early in a speech.

- Assess the ethical and appropriate use of AI tools in brainstorming speech introductions while maintaining personal voice and accuracy.

An effective speech introduction does more than just fill time—it prepares your audience to listen, understand, and engage. While introductions typically make up just 10 to 15 percent of your total speaking time, they hold enormous weight in shaping how your audience perceives you and your message.

Whether you’re speaking in person, recording for digital platforms, or preparing remarks for hybrid or asynchronous audiences, your introduction must do six key things:

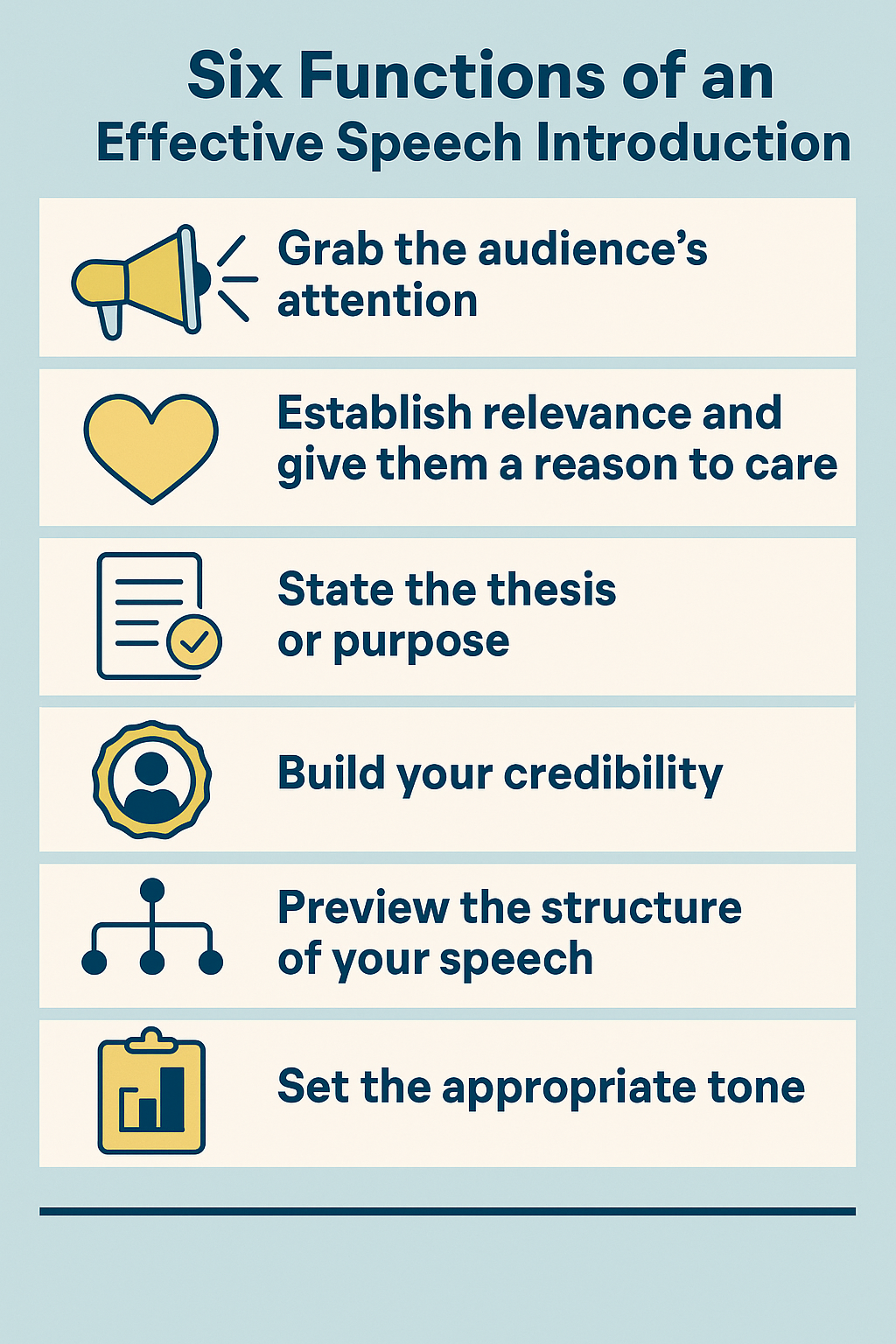

Figure 8.1: Six Functions of an Effective Speech Introduction

Six Introduction Functions Long Description

This circular infographic is divided into six equal segments, each representing a function of an effective speech introduction. Starting at the top and moving clockwise:

- Grab attention – Use an engaging opening to captivate the audience.

- Establish relevance – Give the audience a reason to care.

- State the thesis – Clearly communicate the main idea of your speech.

- Build credibility – Explain why you are trustworthy and prepared.

- Preview the speech – Give an overview of your main points.

- Set the tone – Match your language and delivery style to your purpose and audience.

The functions are arranged in a colorful wheel surrounding a central circle with the heading “The Six Functions of an Effective Introduction”.

Six Introductions Functions Text Transcription

Six Functions of an Effective Speech Introduction

- Grab the audience’s attention

- Establish relevance and give them a reason to care

- State the thesis or purpose

- Build your credibility

- Preview the structure of your speech

- Set the appropriate tone

1. Grab the Audience’s Attention

Before anything else, you need your audience to look up, lean in, or at least not mentally check out. Attention is the currency of communication—and in today’s media-saturated world, it’s in short supply.

Effective attention-getters might include:

- A surprising statistic

- A vivid anecdote

- A rhetorical question

- A powerful quotation

- A brief story

- A relevant joke (if appropriate and ethical)

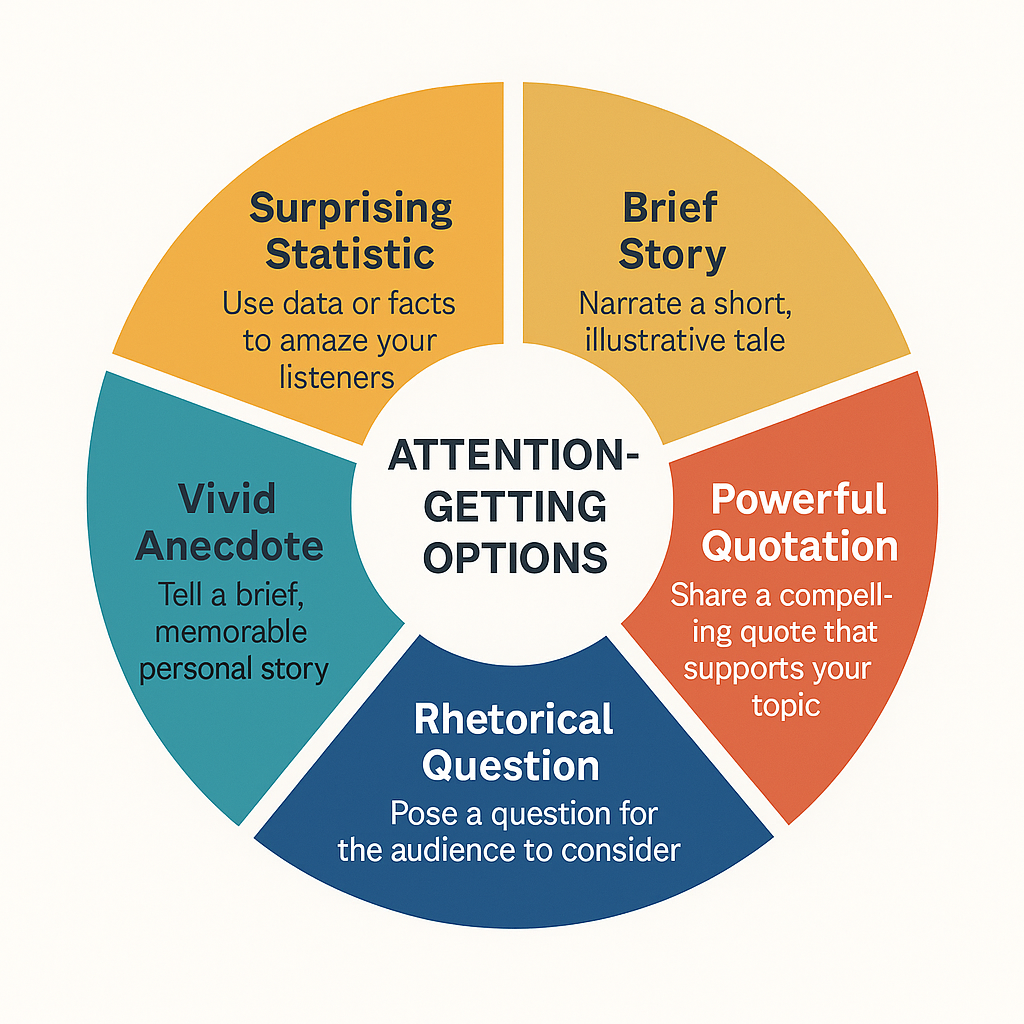

Figure 8.2: Attention-Getting Options for Speech Openings

Attention-Getting Options Long Description

The image is a circular infographic titled “Attention-Getting Options” in the center. Surrounding this central circle are six colored segments, each representing a different method to grab an audience’s attention in a speech introduction. Each method is labeled and described:

- Surprising Statistic (top left, gold):

- Description: “Use data or facts to amaze your listeners.”

- Brief Story (top right, yellow-orange):

- Description: “Narrate a short, illustrative tale.”

- Powerful Quotation (middle right, red-orange):

- Description: “Share a compelling quote that supports your topic.”

- Rhetorical Question (bottom right, navy blue):

- Description: “Pose a question for the audience to consider.”

- Vivid Anecdote (bottom left, teal):

- Description: “Tell a brief, memorable personal story.”

- Surprising Statistic (top left, mustard yellow):

- Repeated description to emphasize a data-driven approach.

Each segment is shaped like a pie slice and evenly spaced around the central circle. The diagram uses bold colors to differentiate each option and is designed to be visually engaging and easy to scan.

Attention-Getting Options Text Transcription

Center:

ATTENTION-GETTING OPTIONS

Surrounding Segments:

- Surprising Statistic

- Use data or facts to amaze your listeners

- Brief Story

- Narrate a short, illustrative tale

- Powerful Quotation

- Share a compelling quote that supports your topic

- Rhetorical Question

- Pose a question for the audience to consider

- Vivid Anecdote

- Tell a brief, memorable personal story

2. Establish Relevance: Give the Audience a Reason to Care

Listeners are more likely to engage if they feel your topic matters to them. Rather than assuming they’ll make the connection on their own, help them understand how your message touches their world, values, or concerns.

Think about what’s meaningful to them, not just to you:

- Will your speech save them time, money, or stress?

- Does it connect to something they’ve recently seen in the news or on campus?

- Does it speak to a challenge they might face in the near future?

This step builds both attention and trust. It also aligns with what communication scholars call receiver-centered communication, which prioritizes the needs, perspectives, and experiences of the audience (Beebe & Beebe, 2022).

3. State the Purpose and Thesis of Your Speech

Your thesis statement is the core idea of your speech. It should be clear, concise, and specific. It often answers the question: What do you want your audience to know, feel, or do by the end of your speech?

Examples:

Weak – “Today I’m going to talk about recycling.”

Strong – “Today I’ll show you how small changes in our daily habits—like how we sort trash or reduce packaging—can significantly reduce landfill waste and environmental harm.”

As public speaking researcher Stephen Lucas (2020) emphasizes, a clear central idea is essential for guiding both the audience’s understanding and the speaker’s structure.

4. Build Credibility (Establish Ethos)

Aristotle called this ethos—the speaker’s credibility. Modern scholars (McCroskey & Teven, 1999) identify three components of credibility:

- Competence: Are you knowledgeable?

- Trustworthiness: Do you seem honest and fair?

- Goodwill: Do you care about the audience’s well-being?

Even in a classroom, you’re not guaranteed credibility—you must demonstrate it. Explain your connection to the topic: experience, passion, or research. Cite strong sources early and avoid exaggerations or misleading claims.

5. Preview the Main Points of the Speech

This is called the preview statement. It tells the audience what’s coming next and shows that your speech is organized. Strong previews function like a GPS for your audience, especially if their attention drifts and needs to reengage.

Example:

“To understand the impact of smart home devices, I’ll first explain how they collect data, then discuss how that data is used by companies, and finally explore what you can do to protect your privacy.”

Baker (1965) found that speakers perceived as disorganized were rated significantly lower in credibility than speakers who gave clear previews and followed them.

6. Set the Tone for the Speech

Introductions don’t just deliver content—they shape expectations. Are you giving a serious policy pitch? A heartfelt personal story? A motivational call to action? Your language, tone, and style should match your purpose and context.

Tone-setting also helps audiences decide how to listen. A humorous opener may signal levity and playfulness, while a solemn story may signal the need for reflection.

If your audience expects something different from your tone (too serious, too casual, too fast, etc.), it can create confusion or discomfort. Think of tone-setting as emotional framing.

Try It: Building a Strong Introduction: Sort the Actions

Activity Introduction: An effective introduction is more than a formality—it’s the launchpad for your speech. This activity will help you distinguish between strategies that strengthen an opening and choices that weaken it, so you can recognize the habits you want to build and the ones you should avoid.

Activity Instructions: Drag each action into the correct category: Good Introduction or Bad Introduction

Wrap-Up: The strongest introductions combine clear purpose, audience connection, and credibility. As you develop your own, aim for choices that invite your audience in, set the right tone, and make them want to hear more.

Summary: Why These Six Functions Matter

An introduction is your chance to shape attention, credibility, structure, and tone. As we move beyond the podium and into hybrid, digital, and AI-augmented communication spaces, these six elements remain essential—but how you achieve them might change. Whether you’re recording a one-minute pitch or standing before a live audience, a strong intro sets everything else in motion.