1 CarResp Case #1307: Paul Griner

GOAL

The goals of this case are for students to explore the pathogenesis of infective endocarditis by recognizing how the virulence of different microbial pathogens, combined with the acute host response to infection, leads to inflammation and injury at the cardiac and systemic levels, and how the underlying valve and dental disease predispose to risk for infective endocarditis.

PAUSE AND REFLECT ON THE GOAL

CASE VIGNETTE

Paul Griner is a 50-year-old man who presents with a fever with chills and 1-2 months of worsening fatigue.

HPI: Mr. Griner is brought to the emergency department by his wife, Linette Griner, who states that he has been having fevers, night sweats, and fatigue for at least one month. Mr. Griner was in his usual state of good health until 2 months ago when he began tiring more and more easily at his job, had to go to bed earlier, and often awoke drenched in sweat. His oral temperature has been as high as 101.5°F. She says she had wanted to have him seen earlier for his symptoms. She is concerned about the fevers and wants to know their cause. She also mentions he’s had a toothache for a month.

No one has been sick at home and he has never traveled outside of Pennsylvania. He avoids dentists because his gums bleed so much, and he rarely sees a physician as he feels he is always well. He has been rubbing an over-the-counter remedy on his sore tooth.

Amy Glick, a scribe working in the ED, who is applying to medical school, catches up with you as you are about to enter the exam room with Mr. Griner. She asks if you would mind if she shadows you on this case. You agree and after the two of you briefly discuss a list of potential differential diagnoses, you go in to meet Mr. Griner.

PMH: Mr. Griner has never been hospitalized or had major surgery. He takes no prescription medicine. He was diagnosed with a heart murmur and mitral valve prolapse (degenerative mitral valve disease) years ago, but only has mild mitral regurgitation and has had no symptoms from it otherwise.

FH: No known history of valvular disease in immediate family members.

SH: He graduated from high school and has worked in a factory full-time ever since then. He does not smoke, and drinks about a six-pack of beer a week. He reports no use of illegal drugs. He has been in a long-term monogamous relationship with his wife.

ROS: He has had no cough, sputum production, dysuria, back or flank pain, headache, or stiff neck. He does not hunt, go hiking, or do any yard work. He has no rashes and does not report any pain. He has no orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, dyspnea on exertion, edema, palpitations, or syncope.

You and Amy compare notes from the history and brainstorm about how this information changes the list of differentials. You discuss what you will be looking for during the physical exam.

PHYSICAL EXAM:

General appearance: On examination, Mr. Griner is a stocky White man wrapped in a blanket and shivering.

VS: Pulse 95, BP 135/55, respirations 22, Temp 38.5°C, height 170 cm (5 ft. 7 in), weight 92 kg (203 lb.); BMI 31.8.

HEENT: There is no tenderness over the sinuses. Tympanic membranes are gray. Cornea and sclerae are clear; fundoscopic exam reveals no Roth spots. Gums are red, swollen, and one shows a little blood. An upper molar on the right is tender to pressure with a tongue blade. Gag reflex is positive.

Neck: There is no adenopathy. Neck veins are flat. Carotids have normal upstroke and amplitude.

Lungs: Clear breath sounds with no dullness to percussion and no egophony.

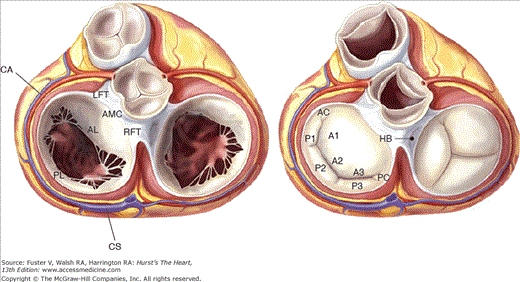

Heart: The point of maximal impulse (PMI) is displaced laterally and is hyperdynamic. Shortly after S1, a loud click is heard followed by a 3/6 plateau-quality late systolic murmur that obscures S2 and radiates toward the base of the heart. After he stands from a squat, the murmur becomes holosystolic and the click merges with S1. There are no gallops, rubs, or diastolic murmurs.

Abdomen: Liver is nontender and nonpulsatile; abdomen is protuberant, soft, and nontender with normoactive bowel sounds. The spleen tip is palpable at the left costal margin.

GU/rectal: Unremarkable.

Extremities: Warm and well-perfused with no cyanosis, clubbing, or edema.

Neurologic: He is oriented x 3 but he has mild weakness and clumsiness of the left hand. When asked, he tells you his hand has been giving him problems during the last week.

Skin: There are splinter hemorrhages under several fingernails and toenails, and a raised, red, tender nodule (Osler’s node) on the tip of the left forefinger.

SNAPPS

Amy is interested in your interpretation of the physical exam findings, and how these findings influence your list of differentials. Amy asks “Are these exam findings unrelated or are they manifestations of the same disease process? Why do they happen? How could his valve disease put him at risk for his current febrile illness?”

The EKG shows normal sinus rhythm and is otherwise unremarkable. The chest X-ray shows clear lung fields and no cardiomegaly. CBC shows a WBC of 14,500/µL (normal 5,000-10,000) and hemoglobin of 12.1 g/dL (normal 13-17). ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate) is 79 (normal<20); CRP (C-reactive protein) is 5.6 (normal <1.0). Electrolytes and liver function tests are normal. Creatinine is 1.3 (normal 0.8-1.3) with a BUN of 24 (normal 9-20). Urinalysis shows 5 RBCs/hpf. Three sets of blood cultures are drawn from 3 different sites over several hours.

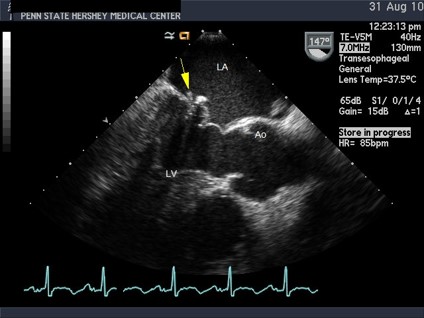

A transthoracic echocardiogram is ordered and you explain to Mr. Griner how important it is to perform this kind of imaging of his heart. The echo shows mild LV dilation with an ejection fraction of 70%. The left atrium is moderately dilated. There is posterior leaflet mitral valve prolapse with moderate to severe mitral regurgitation, increased from mild on his prior echocardiogram. Estimated pulmonary pressure is normal. The mitral leaflets appear thickened, although no definitive vegetation is seen. You ask Amy to investigate what signs on echocardiogram, combined with clinical presentation, suggest chronic (rather than acute) and compensated (rather than decompensated) mitral regurgitation.

A CT scan of the head reveals a small right frontal lobe infarct and two other smaller infarcts in the left frontal lobe. The bilateral infarcts are interpreted as consistent with embolic events. Cardiology and Infectious Disease consultations are called; they agree that endocarditis is likely, but that better visualization of the mitral valve is needed to confirm the diagnosis. A transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) is recommended to confirm the diagnosis of infective endocarditis and to evaluate for valvular and perivalvular complications.

Amy asks if the transesophageal echo would have been needed if his cardiac physical exam had been more normal.

You review the modified Duke Criteria with the Infectious Disease team, to understand the cardiac and systemic manifestations of endocarditis.

Review the modified Duke criteria

Consider how each of the criteria for diagnosis of infective endocarditis reflects an aspect of either microbial pathogenesis and/or a manifestation of host response at the cardiac and systemic levels.

Amy wants to understand what has been happening with Mr. Griner that caused his condition to decline recently. Are all these findings related?

A transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE), repeat EKG, and a Panorex of the teeth are recommended for the next morning. In the setting of probable infective endocarditis, the Cardiology consult team recommends continuous cardiac rhythm monitoring. As he awaits his additional testing, Mr. Griner is wondering what an infection could do to his heart valve and how the TEE might show this.

Mitral Valve Prolapse – 1

Mitral Valve Prolapse – 2

Staph Aureus Endocarditis

Infective Endocarditis – 1

Infective Endocarditis – 2

Posterior leaflet mitral valve prolapse in a parasternal long-axis view

Both mitral valve leaflets are thick and dysplastic, both prolapse into the left atrium, and portions of both leaflets “flail”. That is, their tips point toward the left atrium implying broken mitral chordae. The patient has severe mitral regurgitation (again, no doppler), has excellent left ventricular function, and is asymptomatic.

Severe bileaflet mitral valve prolapsein a parasternal long axis view

(Note from Helen: there are several ways to embed videos using H5P, I created two different versions for us to discuss. I didn’t add in the rest of the videos.)

Treatment with IV vancomycin and low-dose gentamicin is begun after 2 more sets of blood cultures are quickly sent. Mr. Griner wants to know why he has to have so many blood cultures drawn.

In the morning, Mr. Griner reports feeling a little better. The initial blood cultures are found to be growing Gram-positive cocci in pairs and chains.

Amy wants to practice her microbiology knowledge and guess what the bacteria are based on the Gram stain and the morphology. She asks you whether heart valves are always infected with the same organism. In the meantime, Mr. Griner asks why he needs to be on two antibiotics. “Wouldn’t just one antibiotic do the job?” he asks.

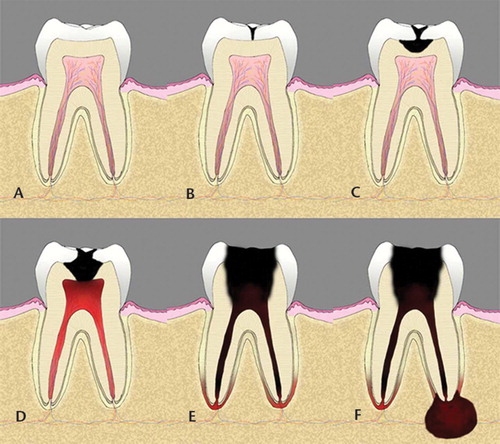

The Panorex shows a peri-apical abscess. A cardiothoracic surgery consult is called, but the surgeon sees no reason to consider surgery yet. She recommends that Mr. Griner see a dentist and have a TEE to exclude mechanical complications such as perivalvular abscess to help guide decision-making regarding possible valve surgery.

Amy, now checking on Mr. Griner out of curiosity, asks what would be an indication for valve surgery in the setting of infective endocarditis.

Rigors recur that evening with a Tmax of 38.7°C. Beyond the persistent fever, Mr. and Mrs. Griner are worried about the potential for valve surgery. Mr. Griner says “When I was first diagnosed with prolapse, I would take antibiotics before going to my dental appointments, but I was told a few years ago by my doctor that this was no longer necessary. Could I have prevented this from happening if I had kept taking antibiotics? What else could I have done?”

The TEE shows a small, oscillating (mobile) vegetation on the mitral valve with a small adjacent leaflet perforation but no abscesses. It is otherwise similar to the transthoracic study.

Over the next few days, his fevers and rigors subside, and after 3 days, new daily blood cultures are sterile. Final identification of the bacterium was an alpha-hemolytic viridans streptococcus sensitive to penicillin G. Antibiotics are changed to penicillin G intravenously. A peripherally-inserted central catheter (PICC) is placed, and Mr. Griner is discharged, to get a total of 4 weeks of antibiotics. An oral surgeon reviewed the Panorex and had to extract one tooth which was abscessed. She found severe gingivitis on oral exam and recommended regular brushing and flossing daily. She helps Mr. Griner schedule routine dental visits every 6 months.

Review the following Pathology images:

- Staph aureus endocarditis. Gross photograph of mitral valve shows irregular, large friable vegetations (verrucous, wart-like) of infectious endocarditis due to Staphylococcus aureus (acute endocarditis), with severe destruction of valve leaflets.

- Infective endocarditis – Low magnification photomicrograph of a full-mount section showing a bacterial vegetation on a valve leaflet.

Review the following echo images:

- Parasternal long axis view of a severely thickened and abnormal prolapsing mitral valve. Compared to the parasternal image, this image shows a valve that is severely thickened and dysplastic. Both leaflets prolapse.

- Transesophageal echo view of a small vegetation on the mitral valve in MVP.

- Transesophageal echo images of an aortic root abscess.

Look at the image below of the pathophysiology of peri-apical abscess formation.

Courtesy Radiographic Society of North America; Journal RadioGraphics

The next time you see Amy, she tells you that she read that Staphyloccocus aureus and Enteroccocus can also cause infective endocarditis. She has a few questions for you: “Would Mr. Griner’s clinical course have been different with those bacterial infections? Do the same antibiotics and treatment work for those as with Streptoccocus viridans? What if he had a prosthetic heart valve, does that make a difference?”

Mr. Griner’s ESR falls to 22, and the anemia and hematuria resolve. He is afebrile, the pulse pressure narrows, and the LV apex is no longer hyperdynamic. He completes the antibiotic course, and follow-up blood cultures are negative. With rehab, his hand recovers reasonably well. He feels well, and returns to work.