7 2.2 Powerful Resources

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Understand that technology is often critical to enabling competitive advantage, and provide examples of firms that have used technology to organize for sustained competitive advantage.

- Understand the value chain concept and be able to examine and compare how various firms organize to bring products and services to market.

- Recognize the role technology can play in crafting an imitation-resistant value chain, as well as when technology choice may render potentially strategic assets less effective.

- Define the following concepts: brand, scale, data and switching cost assets, differentiation, network effects, and distribution channels.

- Understand and provide examples of how technology can be used to create or strengthen the resources mentioned above.

Management has no magic bullets. There is no exhaustive list of key resources that firms can look to in order to build a sustainable business. And recognizing a resource doesn’t mean a firm will be able to acquire it or exploit it forever. But being aware of major sources of competitive advantage can help managers recognize an organization’s opportunities and vulnerabilities, and can help them brainstorm winning strategies. And these assets rarely exist in isolation. Oftentimes, a firm with an effective strategic position can create an arsenal of assets that reinforce one another, creating advantages that are particualrly difficult for rivals to successfully challenge.

Imitation-Resistant Value Chains

While many of the resources below are considered in isolation, the strength of any advantage can be far more significant if firms are able to leverage several of these resources in a way that makes each stronger and makes the firm’s way of doing business more difficult for rivals to match. Firms that craft an imitation-resistant value chain have developed a way of doing business that others will struggle to replicate, and in nearly every successful effort of this kind, technology plays a key enabling role. The value chain is the set of interrelated activities that bring products or services to market (see below). When we compare FreshDirect’s value chain to traditional rivals, there are differences across every element. But most importantly, the elements in FreshDirect’s value chain work together to create and reinforce competitive advantages that others cannot easily copy. Incumbents would be straddled between two business models, unable to reap the full advantages of either. And late-moving pure-play rivals will struggle, as FreshDirect’s lead time allows the firm to develop brand, scale, data, and other advantages that newcomers lack (see below for more on these resources).

Key Framework: The Value Chain

The value chain is the “set of activities through which a product or service is created and delivered to customers.” There are five primary components of the value chain and four supporting components. The primary components are as follows:

- Inbound logistics—getting needed materials and other inputs into the firm from suppliers

- Operations—turning inputs into products or services

- Outbound logistics—delivering products or services to consumers, distribution centers, retailers, or other partners

- Marketing and sales—customer engagement, pricing, promotion, and transaction

- Support—service, maintenance, and customer support

The secondary components are the following:

- Firm infrastructure—functions that support the whole firm, including general management, planning, IS, and finance

- Human resource management—recruiting, hiring, training, and development

- Technology / research and development—new product and process design

- Procurement—sourcing and purchasing functions

While the value chain is typically depicted as it’s displayed in the figure below, goods and information don’t necessarily flow in a line from one function to another. For example, an order taken by the marketing function can trigger an inbound logistics function to get components from a supplier, operations functions (to build a product if it’s not available), or outbound logistics functions (to ship a product when it’s available). Similarly, information from service support can be fed back to advise research and development (R&D) in the design of future products.

When a firm has an imitation-resistant value chain—one that’s tough for rivals to copy while gaining similar benefits—then a firm may have a critical competitive asset. From a strategic perspective, managers can use the value chain framework to consider a firm’s differences and distinctiveness compared to rivals. If a firm’s value chain can’t be copied by competitors without engaging in painful trade-offs, or if the firm’s value chain helps to create and strengthen other strategic assets over time, it can be a key source for competitive advantage. Many of the cases covered in this book, including FreshDirect, Amazon, Zara, Netflix, and eBay, illustrate this point.

An analysis of a firm’s value chain can also reveal operational weaknesses, and technology is often of great benefit to improving the speed and quality of execution. Firms can often buy software to improve things, and tools such as supply chain management (SCM; linking inbound and outbound logistics with operations), customer relationship management (CRM; supporting sales, marketing, and in some cases R&D), and enterprise resource planning software (ERP; software implemented in modules to automate the entire value chain), can have a big impact on more efficiently integrating the activities within the firm, as well as with its suppliers and customers. But remember, these software tools can be purchased by competitors, too. While valuable, such software may not yield lasting competitive advantage if it can be easily matched by competitors as well.

There’s potential danger here. If a firm adopts software that changes a unique process into a generic one, it may have co-opted a key source of competitive advantage particularly if other firms can buy the same stuff. This isn’t a problem with something like accounting software. Accounting processes are standardized and accounting isn’t a source of competitive advantage, so most firms buy rather than build their own accounting software. But using packaged, third-party SCM, CRM, and ERP software typically requires adopting a very specific way of doing things, using software and methods that can be purchased and adopted by others. During its period of PC-industry dominance, Dell stopped deployment of the logistics and manufacturing modules of a packaged ERP implementation when it realized that the software would require the firm to make changes to its unique and highly successful operating model and that many of the firm’s unique supply chain advantages would change to the point where the firm was doing the same thing using the same software as its competitors. By contrast, Apple had no problem adopting third-party ERP software because the firm competes on product uniqueness rather than operational differences.

Dell’s Struggles: Nothing Lasts Forever

Michael Dell enjoyed an extended run that took him from assembling PCs in his dorm room as an undergraduate at the University of Texas at Austin to heading the largest PC firm on the planet. For years Dell’s superefficient, vertically integrated manufacturing and direct-to-consumer model combined to help the firm earn seven times more profit on its own systems when compared with comparably configured rival PCs. And since Dell PCs were usually cheaper, too, the firm could often start a price war and still have better overall margins than rivals.

It was a brilliant model that for years proved resistant to imitation. While Dell sold direct to consumers, rivals had to share a cut of sales with the less efficient retail chains responsible for the majority of their sales. Dell’s rivals struggled in moving toward direct sales because any retailer sensing its suppliers were competing with it through a direct-sales effort could easily chose another supplier that sold a nearly identical product. It wasn’t that HP, IBM, Sony, and so many others didn’t see the advantage of Dell’s model—these firms were wedded to models that made it difficult for them to imitate their rival.

But then Dell’s killer model, one that had become a staple case study in business schools, began to lose steam. Nearly two decades of observing Dell had allowed the contract manufacturers serving Dell’s rivals to improve manufacturing efficiency. Component suppliers located near contract manufacturers, and assembly times fell dramatically. And as the cost of computing fell, the price advantage Dell enjoyed over rivals also shrank in absolute terms. That meant savings from buying a Dell weren’t as big as they once were. On top of that, the direct-to-consumer model also suffered when sales of notebook PCs outpaced the more commoditized desktop market. Notebooks can be considered to be more differentiated than desktops, and customers often want to compare products in person—lift them, type on keyboards, and view screens—before making a purchase decision.

In time, these shifts created an opportunity for rivals to knock Dell from its ranking as the world’s number one PC manufacturer. Dell has even abandoned its direct-only business model and now sells products through third-party brick-and-mortar retailers. Dell’s struggles as computers, customers, and the product mix changed, all underscore the importance of continually assessing a firm’s strategic position among changing market conditions. There is no guarantee that today’s winning strategy will dominate forever.

Brand

A firm’s brand is the symbolic embodiment of all the information connected with a product or service, and a strong brand can also be an exceptionally powerful resource for competitive advantage. Consumers use brands to lower search costs, so having a strong brand is particularly vital for firms hoping to be the first online stop for consumers. Want to buy a book online? Auction a product? Search for information? Which firm would you visit first? Almost certainly Amazon, eBay, or Google. But how do you build a strong brand? It’s not just about advertising and promotion. First and foremost, customer experience counts. A strong brand proxies quality and inspires trust, so if consumers can’t rely on a firm to deliver as promised, they’ll go elsewhere. As an upside, tech can play a critical role in rapidly and cost-effectively strengthening a brand. If a firm performs well, consumers can often be enlisted to promote a product or service (so-called viral marketing). Consider that while scores of dot-coms burned through money on Super Bowl ads and other costly promotional efforts, Google, Hotmail, Skype, eBay, MySpace, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and so many other dominant online properties built multimillion member followings before committing any significant spending to advertising.

Figure 2.3

The “E-mail” and “Share” links at the New York Times Web site enlist customers to spread the word about products and services, user to user, like a virus.

Early customer accolades for a novel service often mean that positive press (a kind of free advertising) will also likely follow.

But show up late and you may end up paying much more to counter an incumbent’s place in the consumer psyche. In recent years, Amazon has spent no money on television advertising, while rivals Buy.com and Overstock.com spent millions. Google, another strong brand, has become a verb, and the cost to challenge it is astonishingly high. Yahoo! and Microsoft’s Bing each spent $100 million on Google-challenging branding campaigns, but the early results of these efforts seemed to do little to grow share at Google’s expense. Branding is difficult, but if done well, even complex tech products can establish themselves as killer brands. Consider that Intel has taken an ingredient product that most people don’t understand, the microprocessor, and built a quality-conveying name recognized by computer users worldwide.

Scale

Many firms gain advantages as they grow in size. Advantages related to a firm’s size are referred to as scale advantages. Businesses benefit from economies of scale when the cost of an investment can be spread across increasing units of production or in serving a growing customer base. Firms that benefit from scale economies as they grow are sometimes referred to as being scalable. Many Internet and tech-leveraging businesses are highly scalable since, as firms grow to serve more customers with their existing infrastructure investment, profit margins improve dramatically.

Consider that in just one year, the Internet firm BlueNile sold as many diamond rings with just 115 employees and one Web site as a traditional jewelry retailer would sell through 116 stores. And with lower operating costs, BlueNile can sell at prices that brick-and-mortar stores can’t match, thereby attracting more customers and further fueling its scale advantages. Profit margins improve as the cost to run the firm’s single Web site and operate its one warehouse is spread across increasing jewelry sales.

A growing firm may also gain bargaining power with its suppliers or buyers. As Dell grew larger, the firm forced suppliers wanting in on Dell’s growing business to make concessions such as locating close to Dell plants. Similarly, for years eBay could raise auction fees because of the firm’s market dominance. Auction sellers who left eBay lost pricing power since fewer bidders on smaller, rival services meant lower prices.

The scale of technology investment required to run a business can also act as a barrier to entry, discouraging new, smaller competitors. Intel’s size allows the firm to pioneer cutting-edge manufacturing techniques and invest $7 billion on next-generation plants. And although Google was started by two Stanford students with borrowed computer equipment running in a dorm room, the firm today runs on an estimated 1.4 million servers. The investments being made by Intel and Google would be cost-prohibitive for almost any newcomer to justify.

Switching Costs and Data

Switching costs exist when consumers incur an expense to move from one product or service to another. Tech firms often benefit from strong switching costs that cement customers to their firms. Users invest their time learning a product, entering data into a system, creating files, and buying supporting programs or manuals. These investments may make them reluctant to switch to a rival’s effort.

Similarly, firms that seem dominant but that don’t have high switching costs can be rapidly trumped by strong rivals. Netscape once controlled more than 80 percent of the market share in Web browsers, but when Microsoft began bundling Internet Explorer with the Windows operating system and (through an alliance) with America Online (AOL), Netscape’s market share plummeted. Customers migrated with a mouse click as part of an upgrade or installation. Learning a new browser was a breeze, and with the Web’s open standards, most customers noticed no difference when visiting their favorite Web sites with their new browser.

Sources of Switching Costs

- Learning costs: Switching technologies may require an investment in learning a new interface and commands.

- Information and data: Users may have to reenter data, convert files or databases, or may even lose earlier contributions on incompatible systems.

- Financial commitment: Can include investments in new equipment, the cost to acquire any new software, consulting, or expertise, and the devaluation of any investment in prior technologies no longer used.

- Contractual commitments: Breaking contracts can lead to compensatory damages and harm an organization’s reputation as a reliable partner.

- Search costs: Finding and evaluating a new alternative costs time and money.

- Loyalty programs: Switching can cause customers to lose out on program benefits. Think frequent purchaser programs that offer “miles” or “points” (all enabled and driven by software).

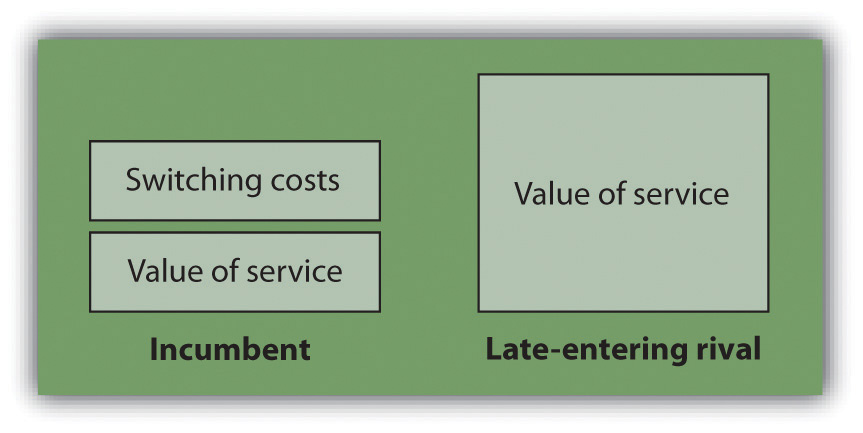

It is critical for challengers to realize that in order to win customers away from a rival, a new entrant must not only demonstrate to consumers that an offering provides more value than the incumbent, they have to ensure that their value added exceeds the incumbent’s value plus any perceived customer switching costs (see Figure 2.4). If it’s going to cost you and be inconvenient, there’s no way you’re going to leave unless the benefits are overwhelming.

Data can be a particularly strong switching cost for firms leveraging technology. A customer who enters her profile into Facebook, movie preferences into Netflix, or grocery list into FreshDirect may be unwilling to try rivals—even if these firms are cheaper—if moving to the new firm means she’ll lose information feeds, recommendations, and time savings provided by the firms that already know her well. Fueled by scale over time, firms that have more customers and have been in business longer can gather more data, and many can use this data to improve their value chain by offering more accurate demand forecasting or product recommendations.

Figure 2.4

In order to win customers from an established incumbent, a late-entering rival must offer a product or service that not only exceeds the value offered by the incumbent but also exceeds the incumbent’s value and any customer switching costs.

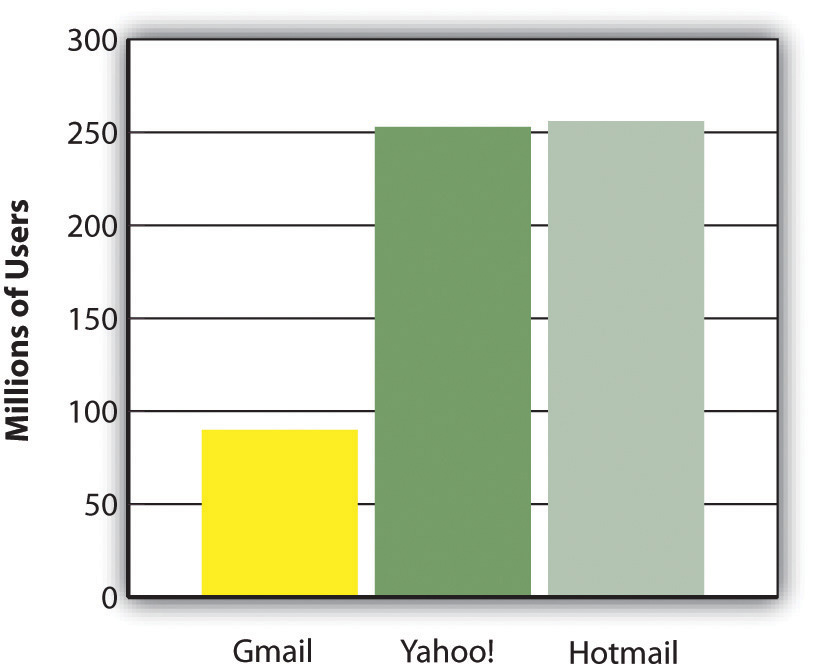

Competing on Tech Alone Is Tough: Gmail versus Rivals

Switching e-mail services can be a real a pain. You’ve got to convince your contacts to update their address books, hope that any message-forwarding from your old service to your new one remains active and works properly, and regularly check the old service to be sure nothing is caught in junk folder purgatory. Not fun. So when Google entered the market for free e-mail, challenging established rivals Yahoo! and Microsoft Hotmail, it knew it needed to offer an overwhelming advantage to lure away customers who had used these other services for years. Google’s offering? A mailbox with vastly more storage than its competitors. With 250 to 500 times the capacity of rivals, Gmail users were liberated from the infamous “mailbox full” error, and could send photos, songs, slideshows, and other rich media files as attachments.

A neat innovation, but one based on technology that incumbents could easily copy. Once Yahoo! and Microsoft saw that customers valued the increased capacity, they quickly increased their own mailbox size, holding on to customers who might otherwise have fled to Google. Four years after Gmail was introduced, the service still had less than half the users of each of its two biggest rivals.

Differentiation

Commodities are products or services that are nearly identically offered from multiple vendors. Consumers buying commodities are highly price-focused since they have so many similar choices. In order to break the commodity trap, many firms leverage technology to differentiate their goods and services. Dell gained attention from customers not only because of its low prices, but also because it was one of the first PC vendors to build computers based on customer choice. Want a bigger hard drive? Don’t need the fast graphics card? Dell will oblige.

Technology has allowed Lands’ End to take this concept to clothing. Now 40 percent of the firm’s chino and jeans orders are for custom products, and consumers pay a price markup of one-third or more for the tailored duds. This kind of tech-led differentiation creates and reinforces other assets. While rivals also offer custom products, Lands’ End has established a switching cost with its customers, since moving to rivals would require twenty minutes to reenter measurements and preferences versus two minutes to reorder from LandsEnd.com. The firm’s reorder rates are 40 to 60 percent on custom clothes, and Lands’ End also gains valuable information on more accurate sizing—critical because current clothes sizes provided across the U.S. apparel industry comfortably fit only about one-third of the population.

Data is not only a switching cost, it also plays a critical role in differentiation. Each time a visitor returns to Amazon, the firm uses browsing records, purchase patterns, and product ratings to present a custom home page featuring products that the firm hopes the visitor will like. Customers value the experience they receive at Amazon so much that the firm received the highest score ever recorded on the University of Michigan’s American Customer Satisfaction Index (ACSI). The score was not just the highest performance of any online firm, it was the highest ranking that any service firm in any industry had ever received.

Capital One has also used data to differentiate its offerings. The firm mines data and runs experiments to create risk models on potential customers. Because of this, the credit card firm aggressively pursued a set of customers that other lenders considered too risky based on simplistic credit scoring. Technology determined that these underserved customers not properly identified by conventional techniques were actually good bets. Finding profitable new markets that others ignored allowed Capital One to grow its EPS (earnings per share) 20 percent a year for seven years, a feat matched by less than 1 percent of public firms.

Network Effects

AOL’s instant messaging client, AIM, has the majority of instant messaging users in the United States. Microsoft Windows has a 90 percent market share in operating systems. EBay has an 80 percent share of online auctions. Why are these firms so dominant? Largely due to the concept of network effects (see Chapter 6 “Understanding Network Effects”). Network effects (sometimes called network externalities or Metcalfe’s Law) exist when a product or service becomes more valuable as more people use it. If you’re the first person with an AIM account, then AIM isn’t very valuable. But with each additional user, there’s one more person to chat with. A firm with a big network of users might also see value added by third parties. Sony’s PlayStation 2 dominated the prior generation of video game consoles in large part because it had more games than its rivals, and most of these games were provided by firms other than Sony. Third-party add-on products, books, magazines, or even skilled labor are all attracted to networks of the largest number of users, making dominant products more valuable.

Switching costs also play a role in determining the strength of network effects. Tech user investments often go far beyond simply the cost of acquiring a technology. Users spend time learning a product; they buy add-ons, create files, and enter preferences. Because no one wants to be stranded with an abandoned product and lose this additional investment, users may choose a technically inferior product simply because the product has a larger user base and is perceived as having a greater chance of being offered in the future. The virtuous cycle of network effectsA virtuous adoption cycle occurs when network effects exist that make a product or service more attractive (increases benefits, reduces costs) as the adopter base grows. doesn’t apply to all tech products, and it can be a particularly strong asset for firms that can control and leverage a leading standard (think Apple’s iPhone and iPad with their closed systems versus Netscape, which was almost entirely based on open standards), but in some cases where network effects are significant, they can create winners so dominant that firms with these advantages enjoy a near-monopoly hold on a market.

Distribution Channels

If no one sees your product, then it won’t even get considered by consumers. So distribution channels—the path through which products or services get to customers—can be critical to a firm’s success. Again, technology opens up opportunities for new ways to reach customers.

Users can be recruited to create new distribution channels for your products and services (usually for a cut of the take). You may have visited Web sites that promote books sold on Amazon.com. Web site operators do this because Amazon gives them a percentage of all purchases that come in through these links. Amazon now has over 1 million of these “associates” (the term the firm uses for its affiliates), yet it only pays them if a promotion gains a sale. Google similarly receives some 30 percent of its ad revenue not from search ads, but from advertisements distributed within third-party sites ranging from lowly blogs to the New York Times.

In recent years, Google and Microsoft have engaged in bidding wars, trying to lock up distribution deals that would bundle software tools, advertising, or search capabilities with key partner offerings. Deals with partners such as Dell, MySpace, and Verizon Wireless have been valued at up to $1 billion each.

The ability to distribute products by bundling them with existing offerings is a key Microsoft advantage. But beware—sometimes these distribution channels can provide firms with such an edge that international regulators have stepped in to try to provide a more level playing field. Microsoft was forced by European regulators to unbundle the Windows Media Player, for fear that it provided the firm with too great an advantage when competing with the likes of RealPlayer and Apple’s QuickTime (see Chapter 6 “Understanding Network Effects”).

What about Patents?

Intellectual property protection can be granted in the form of a patent for those innovations deemed to be useful, novel, and nonobvious. In the United States, technology and (more controversially) even business models can be patented, typically for periods of twenty years from the date of patent application. Firms that receive patents have some degree of protection from copycats that try to identically mimic their products and methods.

The patent system is often considered to be unfairly stacked against start-ups. U.S. litigation costs in a single patent case average about $5 million, and a few months of patent litigation can be enough to sink an early stage firm. Large firms can also be victims. So-called patent trolls hold intellectual property not with the goal of bringing novel innovations to market but instead in hopes that they can sue or extort large settlements from others. BlackBerry maker Research in Motion’s $612 million settlement with the little-known holding company NTP is often highlighted as an example of the pain trolls can inflict.

Even if an innovation is patentable, that doesn’t mean that a firm has bulletproof protection. Some patents have been nullified by the courts upon later review (usually because of a successful challenge to the uniqueness of the innovation). Software patents are also widely granted, but notoriously difficult to defend. In many cases, coders at competing firms can write substitute algorithms that aren’t the same, but accomplish similar tasks. For example, although Google’s PageRank search algorithms are fast and efficient, Microsoft, Yahoo! and others now offer their own noninfringing search that presents results with an accuracy that many would consider on par with PageRank. Patents do protect tech-enabled operations innovations at firms like Netflix and Harrah’s (casino hotels), and design innovations like the iPod click wheel. But in a study of the factors that were critical in enabling firms to profit from their innovations, Carnegie Mellon professor Wes Cohen found that patents were only the fifth most important factor. Secrecy, lead time, sales skills, and manufacturing all ranked higher.

Key Takeaways

- Technology can play a key role in creating and reinforcing assets for sustainable advantage by enabling an imitation-resistant value chain; strengthening a firm’s brand; collecting useful data and establishing switching costs; creating a network effect; creating or enhancing a firm’s scale advantage; enabling product or service differentiation; and offering an opportunity to leverage unique distribution channels.

- The value chain can be used to map a firm’s efficiency and to benchmark it against rivals, revealing opportunities to use technology to improve processes and procedures. When a firm is resistant to imitation, its value chain may yield sustainable competitive advantage.

- Firms may consider adopting packaged software or outsourcing value chain tasks that are not critical to a firm’s competitive advantage. A firm should be wary of adopting software packages or outsourcing portions of its value chain that are proprietary and a source of competitive advantage.

- Patents are not necessarily a sure-fire path to exploiting an innovation. Many technologies and business methods can be copied, so managers should think about creating assets like the ones defined above if they wish to create truly sustainable advantage.

- Nothing lasts forever, and shifting technologies and market conditions can render once strong assets as obsolete.

Questions and Exercises

- Define and diagram the value chain.

- Discuss the elements of FreshDirect’s value chain and the technologies that FreshDirect uses to give the firm a competitive advantage. Why is FreshDirect resistant to imitation from incumbent firms? What advantages does FreshDirect have that insulate the firm from serious competition from start-ups copying its model?

- Which firm should adopt third-party software to automate its supply chain—Dell or Apple? Why? Identify another firm that might be at risk if adopting generic enterprise software. Why do you think this is risky and what would they do as an alternative?

- Identify two firms in the same industry that have different value chains. Why do you think these firms have different value chains? What role do you think technology plays in the way that each firm competes? Do these differences enable strategic positioning? Why or why not?

- How can information technology help a firm build a brand inexpensively?

- Describe BlueNile’s advantages over a traditional jewelry chain. Can conventional jewelers successfully copy BlueNile? Why or why not?

- What are switching costs? What role does technology play in strengthening a firm’s switching costs?

- In most markets worldwide, Google dominates search. Why hasn’t Google shown similar dominance in e-mail, as well?

- Should Lands’ End fear losing customers to rivals that copy its custom clothing initiative? Why or why not?

- How can technology be a distribution channel? Name a firm that has tried to leverage its technology as a distribution channel.

- Do you think it is possible to use information technology to achieve competitive advantage? If so, how? If not, why not?

- What are network effects? Name a product or service that has been able to leverage network effects to its advantage.

- For well over a decade, Dell earned above average industry profits. But lately the firm has begun to struggle. What changed?

- What are the potential sources of switching costs if you decide to switch cell phone service providers? Cell phones? Operating systems? PayTV service?

- Why is an innovation based on technology alone often subjected to intense competition?

- Can you think of firms that have successfully created competitive advantage even though other firms provide essentially the same thing? What factors enable this success?

- What role did network effects play in your choice of an instant messaging client? Of an operating system? Of a social network? Of a word processor? Why do so many firms choose to standardize on Microsoft Windows?

- What can a firm do to prepare for the inevitable expiration of a patent (patents typically expire after twenty years)? Think in terms of the utilization of other assets and the development of advantages through employment of technology.

References

Davenport, T., and J. Harris, Competing on Analytics: The New Science of Winning (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2007).

Edwards, J., “JWT’s $100 Million Campaign for Microsoft’s Bing Is Failing,” BNET, July 16, 2009.

Feld, B., “Why the Decks Are Stacked against Software Startups in Patent Litigation,” Technology Review, April 12, 2009.

Flatley, J., “Intel Invests $7 Billion in Stateside 32nm Manufacturing,” Engadget, February 10, 2009.

Friscia, T., K. O’Marah, D. Hofman, and J. Souza, “The AMR Research Supply Chain Top 25 for 2009,” AMR Research, May 28, 2009, http://www.amrresearch.com/Content/View.aspx?compURI=tcm:7-43469.

Google Fourth Quarter 2008 Earnings Summary, http://investor.google.com/earnings.html.

Graham, J., “E-mail Carriers Deliver Gifts of Nifty Features to Lure, Keep Users,” USA Today, April 16, 2008.

Katz, R., “Tech Titans Building Boom,” IEEE Spectrum 46, no. 2 (February 1, 2009): 40–43.

M. Porter, “Strategy and the Internet,” Harvard Business Review 79, no. 3 (March 2001): 62–78.

Mullaney T., and S. Ante, “InfoWars,” BusinessWeek, June 5, 2000.

Mullaney, T., “Jewelry Heist,” BusinessWeek, May 10, 2004.

Porter, M., “Strategy and the Internet,” Harvard Business Review 79, no. 3 (March 2001): 62–78.

Schlosser, J., “Cashing In on the New World of Me,” Fortune, December 1, 2004.

Shapiro, C., and H. Varian, (Adapted from) “Locked In, Not Locked Out,” Industry Standard, November 2–9, 1998.

Wingfield, N., “Microsoft Wins Key Search Deals,” Wall Street Journal, January 8, 2009.

Wu, T., “Weapons of Business Destruction,” Slate, February 6, 2006; R. Kelley, “BlackBerry Maker, NTP Ink $612 Million Settlement,” CNN Money, March 3, 2006.