36 7.9 Get SMART: The Social Media Awareness and Response Team

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Illustrate several examples of effective and poor social media use.

- Recognize the skills and issues involved in creating and staffing an effective social media awareness and response team (SMART).

- List and describe key components that should be included in any firm’s social media policy.

- Understand the implications of ethical issues in social media such as “sock puppetry” and “astroturfing” and provide examples and outcomes of firms and managers who used social media as a vehicle for dishonesty.

- List and describe tools for monitoring social media activity relating to a firm, its brands, and staff.

- Understand issues involved in establishing a social media presence, including the embassy approach, openness, and staffing.

- Discuss how firms can engage and respond through social media, and how companies should plan for potential issues and crises.

For an example of how outrage can go viral, consider Dave Carroll1. The Canadian singer-songwriter was traveling with his band Sons of Maxwell on a United Airlines flight from Nova Scotia to Nebraska when, during a layover at Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport, Carroll saw baggage handlers roughly tossing his guitar case. The musician’s $3,500 Taylor guitar was in pieces by the time it arrived in Omaha. In the midst of a busy tour schedule, Carroll didn’t have time to follow up on the incident until after United’s twenty-four-hour period for filing a complaint for restitution had expired. When United refused to compensate him for the damage, Carroll penned the four-minute country ditty “United Breaks Guitars,” performed it in a video, and uploaded the clip to YouTube (sample lyrics: “I should have gone with someone else or gone by car…’cuz United breaks guitars”). Carroll even called out the unyielding United rep by name. Take that, Ms. Irlwig! (Note to customer service reps everywhere: you’re always on.)

The clip went viral, receiving 150,000 views its first day and five million more by the next month. Well into the next year, “United Breaks Guitars” remained the top result on YouTube when searching the term “United.” No other topic mentioning that word—not “United States,” “United Nations,” or “Manchester United”—ranked ahead of this one customer’s outrage.

Video

Dave Carroll’s ode to his bad airline experience, “United Breaks Guitars,” went viral, garnering millions of views.

Scarring social media posts don’t just come from outside the firm. Earlier that same year employees of Domino’s Pizza outlet in Conover, North Carolina, created what they thought would be a funny gross-out video for their friends. Posted to YouTube, the resulting footage of the firm’s brand alongside vile acts of food prep was seen by over one million viewers before it was removed. Over 4.3 million references to the incident can be found on Google, and many of the leading print and broadcast outlets covered the story. The perpetrators were arrested, the Domino’s storefront where the incident occurred was closed, and the firm’s president made a painful apology (on YouTube, of course).

Not all firms choose to aggressively engage social media. As of this writing some major brands still lack a notable social media presence (Apple comes immediately to mind). But your customers are there and they’re talking about your organization, its products, and its competitors. Your employees are there, too, and without guidance, they can step on a social grenade with your firm left to pick out the shrapnel. Soon, nearly everyone will carry the Internet in their pocket. Phones and MP3 players are armed with video cameras capable of recording every customer outrage, corporate blunder, ethical lapse, and rogue employee. Social media posts can linger forever online, like a graffiti tag attached to your firm’s reputation. Get used to it—that genie isn’t going back in the bottle.

As the “United Breaks Guitars” and “Domino’s Gross Out” incidents show, social media will impact a firm whether it chooses to engage online or not. An awareness of the power of social media can shape customer support engagement and crisis response, and strong corporate policies on social media use might have given the clueless Domino’s pranksters a heads-up that their planned video would get them fired and arrested. Given the power of social media, it’s time for all firms to get SMART, creating a social media awareness and response team. While one size doesn’t fit all, this section details key issues behind SMART capabilities, including creating the social media team, establishing firmwide policies, monitoring activity inside and outside the firm, establishing the social media presence, and managing social media engagement and response.

Creating the Team

Firms need to treat social media engagement as a key corporate function with clear and recognizable leadership within the organization. Social media is no longer an ad hoc side job or a task delegated to an intern. When McDonald’s named its first social media chief, the company announced that it was important to have someone “dedicated 100% of the time, rather than someone who’s got a day job on top of a day job” (York, 2010). Firms without social media baked into employee job functions often find that their online efforts are started with enthusiasm, only to suffer under a lack of oversight and follow-through. One hotel operator found franchisees were quick to create Facebook pages, but many rarely monitored them. Customers later notified the firm that unmonitored hotel “fan” pages contained offensive messages—a racist rant on one, paternity claims against an employee on another.

Organizations with a clearly established leadership role for social media can help create consistency in firm dialogue; develop and communicate policy; create and share institutional knowledge; provide training, guidance, and suggestions; offer a place to escalate issues in the event of a crisis or opportunity; and catch conflicts that might arise if different divisions engage without coordination.

While firms are building social media responsibility into job descriptions, also recognize that social media is a team sport that requires input from staffers throughout an organization. The social media team needs support from public relations, marketing, customer support, HR, legal, IT, and other groups, all while acknowledging that what’s happening in the social media space is distinct from traditional roles in these disciplines. The team will hone unique skills in technology, analytics, and design, as well as skills for using social media for online conversations, listening, trust building, outreach, engagement, and response. As an example of the interdisciplinary nature of social media practice, consider that the social media team at Starbucks (regarded by some as the best in the business) is organized under the interdisciplinary “vice president of brand, content, and online2.”

Also note that while organizations with SMARTs (social media teams) provide leadership, support, and guidance, they don’t necessarily drive all efforts. GM’s social media team includes representatives from all the major brands. The idea is that employees in the divisions are still the best to engage online once they’ve been trained and given operational guardrails. Says GM’s social media chief, “I can’t go in to Chevrolet and tell them ‘I know your story better than you do, let me tell it on the Web’” (Barger, 2009)3. Similarly, the roughly fifty Starbucks “Idea Partners” who participate in MyStarbucksIdea are specialists. Part of their job is to manage the company’s social media. In this way, conversations about the Starbucks Card are handled by card team experts, and merchandise dialogue has a product specialist who knows that business best. Many firms find that the social media team is key for coordination and supervision (e.g., ensuring that different divisions don’t overload consumers with too much or inconsistent contact), but the dynamics of specific engagement still belong with the folks who know products, services, and customers best.

Responsibilities and Policy Setting

In an age where a generation has grown up posting shoot-from-the-hip status updates and YouTube is seen as a fame vehicle for those willing to perform sensational acts, establishing corporate policies and setting employee expectations are imperative for all organizations. The employees who don’t understand the impact of social media on the firm can do serious damage to their employers and their careers (look to Domino’s for an example of what can go wrong).

Many experts suggest that a good social media policy needs to be three things: “short, simple, and clear” (Soat, 2010). Fortunately, most firms don’t have to reinvent the wheel. Several firms, including Best Buy, IBM, Intel, The American Red Cross, and Australian telecom giant Telstra, have made their social media policies public.

Most guidelines emphasize the “three Rs”: representation, responsibility, and respect.

- Representation. Employees need clear and explicit guidelines on expectations for social media engagement. Are they empowered to speak on behalf of the firm? If they do, it is critical that employees transparently disclose this to avoid legal action. U.S. Federal Trade Commission rules require disclosure of relationships that may influence online testimonial or endorsement. On top of this, many industries have additional compliance requirements (e.g., governing privacy in the health and insurance fields, retention of correspondence and disclosure for financial services firms). Firms may also want to provide guidelines on initiating and conducting dialogue, when to respond online, and how to escalate issues within the organization.

- Responsibility. Employees need to take responsibility for their online actions. Firms must set explicit expectations for disclosure, confidentiality and security, and provide examples of engagement done right, as well as what is unacceptable. An effective social voice is based on trust, so accuracy, transparency, and accountability must be emphasized. Consequences for violations should be clear.

- Respect. Best Buy’s policy for its Twelpforce explicitly states participants must “honor our differences” and “act ethically and responsibly.” Many employees can use the reminder. Sure customer service is a tough task and every rep has a story about an unreasonable client. But there’s a difference between letting off steam around the water cooler and venting online. Virgin Atlantic fired thirteen of the airline’s staffers after they posted passenger insults and inappropriate inside jokes on Facebook (Conway, 2008).

Policies also need to have teeth. Remember, a fourth “R” is at stake—reputation (both the firm’s and the employee’s). Violators should know the consequences of breaking firm rules and policies should be backed by action. Best Buy’s policy simply states, “Just in case you are forgetful or ignore the guidelines above, here’s what could happen. You could get fired (and it’s embarrassing to lose your job for something that’s so easily avoided).”

Despite these concerns, trying to micromanage employee social media use is probably not the answer. At IBM, rules for online behavior are surprisingly open. The firm’s code of conduct reminds employees to remember privacy, respect, and confidentiality in all electronic communications. Anonymity is not permitted on IBM’s systems, making everyone accountable for their actions. As for external postings, the firm insists that employees not disparage competitors or reveal customers’ names without permission and asks that any employee posts from IBM accounts or that mention the firm also include disclosures indicating that opinions and thoughts shared publicly are the individual’s and not Big Blue’s.

Some firms have more complex social media management challenges. Consider hotels and restaurants where outlets are owned and operated by franchisees rather than the firm. McDonald’s social media team provides additional guidance so that regional operations can create, for example, a Twitter handle (e.g., @mcdonalds_cincy) that handle a promotion in Cincinnati that might not run in other regions (York, 2010). A social media team can provide coordination while giving up the necessary control. Without this kind of coordination, customer communication can quickly become a mess.

Training is also a critical part of the SMART mandate. GM offers an intranet-delivered video course introducing newbies to the basics of social media and to firm policies and expectations. GM also trains employees to become “social media proselytizers and teachers.” GM hopes this approach enables experts to interact directly with customers and partners, allowing the firm to offer authentic and knowledgeable voices online.

Training should also cover information security and potential threats. Social media has become a magnet for phishing, virus distribution, and other nefarious online activity. Over one-third of social networking users claim to have been sent malware via social networking sites (see Chapter 13 “Information Security: Barbarians at the Gateway (and Just About Everywhere Else)”). The social media team will need to monitor threats and spread the word on how employees can surf safe and surf smart.

Since social media is so public, it’s easy to amass examples of what works and what doesn’t, adding these to the firm’s training materials. The social media team provides a catch point for institutional knowledge and industry best practice; and the team can update programs over time as new issues, guidelines, technologies, and legislation emerge.

The social media space introduces a tension between allowing expression (among employees and by the broader community) and protecting the brand. Firms will fall closer to one end or the other of this continuum depending on compliance requirements, comfort level, and goals. Expect the organization’s position to move. Firms will be cautious as negative issues erupt, others will jump in as new technologies become hot and early movers generate buzz and demonstrate results. But it’s the SMART responsibility to avoid knee-jerk reaction and to shepherd firm efforts with the professionalism and discipline of other management domains.

Astroturfing and Sock Puppets

Social media can be a cruel space. Sharp-tongued comments can shred a firm’s reputation and staff might be tempted to make anonymous posts defending or promoting the firm. Don’t do it! Not only is it a violation of FTC rules, IP addresses and other online breadcrumbs often leave a trail that exposes deceit.

Whole Foods CEO John Mackey fell victim to this kind of temptation, but his actions were eventually, and quite embarrassingly, uncovered. For years, Mackey used a pseudonym to contribute to online message boards, talking up Whole Foods stock and disparaging competitors. When Mackey was unmasked, years of comments were publicly attributed to him. The New York Times cited one particularly cringe-worthy post where Mackey used the pseudonym to complement his own good looks, writing, “I like Mackey’s haircut. I think he looks cute” (Martin, 2007)!

Fake personas set up to sing your own praises are known as sock puppets among the digerati, and the practice of lining comment and feedback forums with positive feedback is known as astroturfing. Do it and it could cost you. The firm behind the cosmetic procedure known as the Lifestyle Lift was fined $300,000 in civil penalties after the New York Attorney General’s office discovered that the firm’s employees had posed as plastic surgery patients and wrote glowing reviews of the procedure (Miller, 2009).

Review sites themselves will also take action. TripAdvisor penalizes firms if it’s discovered that customers are offered some sort of incentive for posting positive reviews. The firm also employs a series of sophisticated automated techniques as well as manual staff review to uncover suspicious activity. Violators risk penalties that include being banned from the service.

Your customers will also use social media keep you honest. Several ski resorts have been embarrassed when tweets and other social media posts exposed them as overstating snowfall results. There’s even an iPhone app skiers can use to expose inaccurate claims (Rathke, 2010).

So keep that ethical bar high—you never know when technology will get sophisticated enough to reveal wrongdoings.

Monitoring

Concern over managing a firm’s online image has led to the rise of an industry known as online reputation management. Firms specializing in this field will track a client firm’s name, brand, executives’ names, or other keywords, reporting online activity and whether sentiment trends toward the positive or negative.

But social media monitoring is about more than about managing one’s reputation; it also provides critical competitive intelligence, it can surface customer support issues, and it can uncover opportunities for innovation and improvement. Firms that are quick to lament the very public conversations about their brands happening online need to embrace social media as an opportunity to learn more.

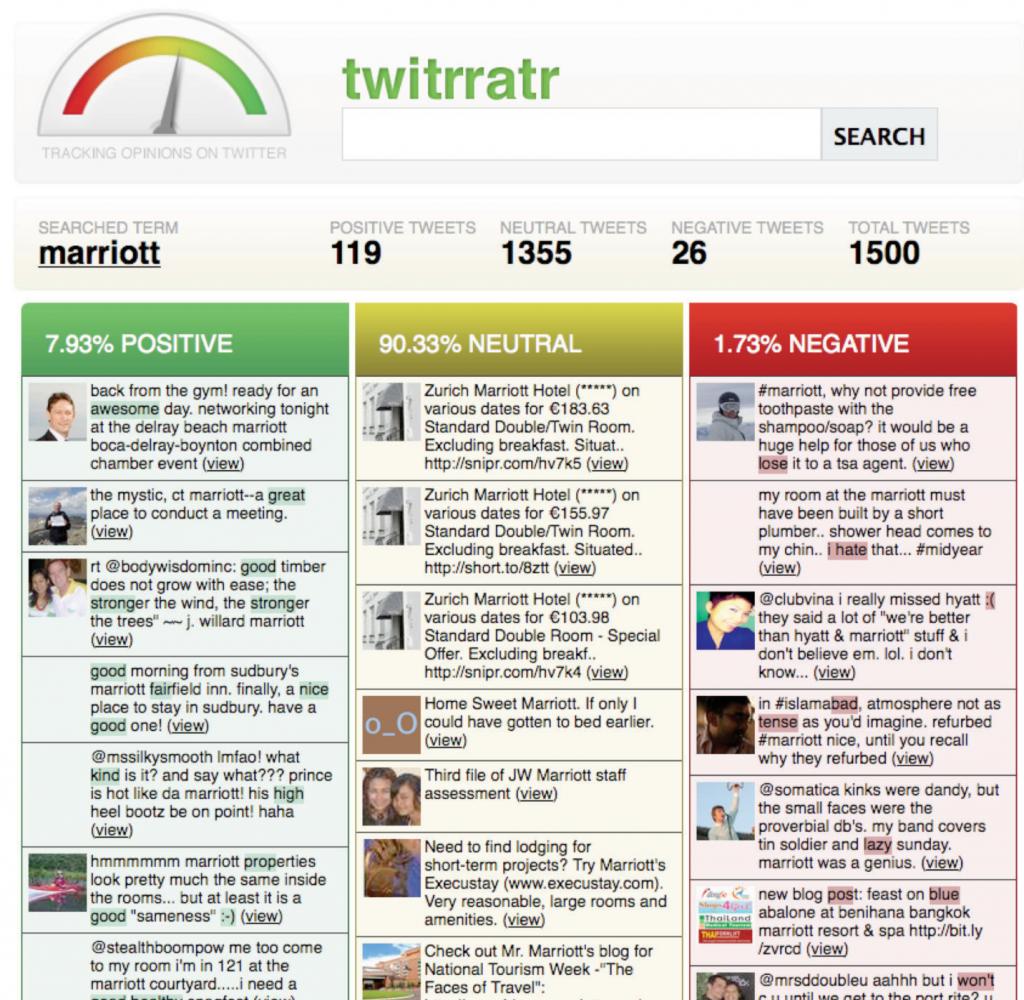

Resources for monitoring social media are improving all the time, and a number of tools are available for free. All firms can take advantage of Google Alerts, which flag blog posts, new Web pages, and other publicly accessible content, regularly delivering a summary of new links to your mailbox (for more on using Google for intelligence gathering, see Chapter 14 “Google: Search, Online Advertising, and Beyond”). Twitter search and third-party Twitter clients like TweetDeck can display all mentions of a particular term. Tools like Twitrratr will summarize mentions of a phrase and attempt to classify tweets as “positive,” “neutral,” or “negative.”

Figure 7.5

Tools like Twitrratr attempt to classify the sentiment behind tweets mentioning a key word or phrase. Savvy firms can mine comments for opportunities to provide thoughtful customer service (like the suggestion at the top right to provide toothpaste for those who lose it in U.S. airport security).

Facebook provides a summary of fan page activity to administrators (including stats on visits, new fans, wall posts, etc.), while Facebook’s Insights tool measures user exposure, actions, and response behavior relating to a firm’s Facebook pages and ads.

Bit.ly and many other URL-shortening services allow firms to track Twitter references to a particular page. Since bit.ly applies the same shortened URL to all tweets pointing to a page, it allows firms to follow not only if a campaign has been spread through “retweeting” but also if new tweets were generated outside of a campaign. Graphs plot click-throughs over time, and a list of original tweets can be pulled up to examine what commentary accompanied a particular link.

Location-based services like Foursquare have also rolled out robust tools for monitoring how customers engage with firms in the brick-and-mortar world. Foursquare’s analytics and dashboard present firms with a variety of statistics, such as who has “checked in” and when, a venue’s male-to-female ratio, and which times of day are more active for certain customers. “Business owners will also be able to offer instant promotions to try to engage new customers and keep current ones” (Bolton, 2010). Managers can use the tools to notice if a once-loyal patron has dropped off the map, potentially creating a special promotion to lure her back.

Monitoring should also not be limited to customers and competitors. Firms are leveraging social media both inside their firms and via external services (e.g., corporate groups on Facebook and LinkedIn), and these spaces should also be on the SMART radar. This kind of monitoring can help firms keep pace with employee sentiment and insights, flag discussions that may involve proprietary information or other inappropriate topics, and provide guidance for those who want to leverage social media for the firm’s staff—that is, anything from using online tools to help organize the firm’s softball league to creating a wiki for a project group. Social media are end-user services that are particularly easy to deploy but that can also be used disastrously and inappropriately, so it’s vital for IT experts and other staffers on the social media team to be visible and available, offering support and resources for those who want to take a dip into social media’s waters.

Establishing a Presence

Firms hoping to get in on the online conversation should make it easy for their customers to find them. Many firms take an embassy approach to social media, establishing presence at various services with a consistent name. Think facebook.com/starbucks, twitter.com/starbucks, youtube.com/starbucks, flickr.com/starbucks, and so on. Corporate e-mail and Web sites can include icons linking to these services in a header or footer. The firm’s social media embassies can also be highlighted in physical space such as in print, on bags and packaging, and on store signage. Firms should try to ensure that all embassies carry consistent design elements, so users see familiar visual cues that underscore they are now at a destination associated with the organization.

As mentioned earlier, some firms establish their own communities for customer engagement. Examples include Dell’s IdeaStorm and MyStarbucksIdea. Not every firm has a customer base that is large and engaged enough to support hosting its own community. But for larger firms, these communities can create a nexus for feedback, customer-driven innovation, and engagement.

Customers expect an open dialogue, so firms engaging online should be prepared to deal with feedback that’s not all positive. Firms are entirely within their right to screen out offensive and inappropriate comments. Noting this, firms might think twice before turning on YouTube comments (described as “the gutter of the Internet” by one leading social media manager) (Nelson, 2010). Such comments could expose employees or customers profiled in clips to withering, snarky ridicule. However, firms engaged in curating their forums to present only positive messages should be prepared for the community to rebel and for embarrassing cries of censorship to be disclosed. Firms that believe in the integrity of their work and the substance of their message shouldn’t be afraid. While a big brand like Starbucks is often a target of criticism, social media also provides organizations with an opportunity to respond fairly to that criticism and post video and photos of the firm’s efforts. In Starbucks’ case, the firm shares its work investing in poor coffee-growing communities as well as efforts to support AIDS relief. A social media presence allows a firm to share these works without waiting for conventional public relations (PR) to yield results or for journalists to pick up and interpret the firm’s story. Starbucks executives have described the majority of comments the company receives through social media as “a love letter to the firm.” By contrast, if your firm isn’t prepared to be open or if your products and services are notoriously subpar and your firm is inattentive to customer feedback, then establishing a brand-tarring social media beachhead might not make sense. A word to the self-reflective: Customer conversations will happen online even if you don’t have any social media embassies. Users can form their own groups, hash tags, and forums. A reluctance to participate may signal that the firm is facing deeper issues around its product and service.

While firms can learn a lot from social media consultants and tool providers, it’s considered bad practice to outsource the management of a social media presence to a third-party agency. The voice of the firm should come from the firm. In fact, it should come from employees who can provide authentic expertise. Starbucks’ primary Twitter feed is managed by Brad Nelson, a former barista, while the firm’s director of environmental affairs, Jim Hanna, tweets and engages across social media channels on the firm’s green efforts.

Engage and Respond

Having an effective social media presence offers “four Ms” of engagement: it’s a megaphone allowing for outbound communication; it’s a magnet drawing communities inward for conversation; and it allows for monitoring and mediation of existing conversations (Gallaugher & Ransbotham, 2009). This dialogue can happen privately (private messaging is supported on most services) or can occur very publicly (with the intention to reach a wide audience). Understanding when, where, and how to engage and respond online requires a deft and experienced hand.

Many firms will selectively and occasionally retweet praise posts, underscoring the firm’s commitment to customer service. Highlighting service heroes also reinforces exemplar behavior to employees who may be following the firm online, too. Users are often delighted when a major brand retweets their comments, posts a comment on their blog, or otherwise acknowledges them online—just be sure to do a quick public profile investigation to make sure your shout-outs are directed at customers you want associated with your firm. Escalation procedures should also include methods to flag noteworthy posts, good ideas, and opportunities that the social media team should be paying attention to. The customer base is often filled with heartwarming stories of positive customer experiences and rich with insight on making good things even better.

Many will also offer an unsolicited apology if the firm’s name or products comes up in a disgruntled post. You may not be able to respond to all online complaints, but selective acknowledgement of the customer’s voice (and attempts to address any emergent trends) is a sign of a firm that’s focused on customer care. Getting the frequency, tone, and cadence for this kind of dialogue is more art than science, and managers are advised to regularly monitor other firms with similar characteristics for examples of what works and what doesn’t.

Many incidents can be responded to immediately and with clear rules of engagement. For example, Starbuck issues corrective replies to the often-tweeted urban legend that the firm does not send coffee to the U.S. military because of a corporate position against the war. A typical response might read, “Not true, get the facts here” with a link to a Web page that sets the record straight.

Reaching out to key influencers can also be extremely valuable. Prominent bloggers and other respected social media participants can provide keen guidance and insight. The goal isn’t to create a mouthpiece, but to solicit input, gain advice, gauge reaction, and be sure your message is properly interpreted. Influencers can also help spread accurate information and demonstrate a firm’s commitment to listening and learning. In the wake of the Domino’s gross-out, executives reached out to the prominent blog The Consumerist (Jacques, 2009). Facebook has solicited advice and feedback from MoveOn.org months before launching new features (Stone, 2008). Meanwhile, Kaiser Permanente leveraged advice from well-known health care bloggers in crafting its approach to social media (Kane, et. al., 2009).

However, it’s also important to recognize that not every mention is worthy of a response. The Internet is filled with PR seekers, the unsatisfiably disgruntled, axe grinders seeking to trap firms, dishonest competitors, and inappropriate groups of mischief makers commonly referred to as trolls. One such group hijacked Time Magazine’s user poll of the World’s Most Influential People, voting their twenty-one-year-old leader to the top of the list ahead of Barack Obama, Vladimir Putin, and the pope. Prank voting was so finely calibrated among the group that the rankings list was engineered to spell out a vulgar term using the first letter of each nominee’s name (Schonfeld, 2009).

To prepare, firms should “war game” possible crises, ensuring that everyone knows their role, and that experts are on call. A firm’s social media policy should also make it clear how employees who spot a crisis might “pull the alarm” and mobilize the crisis response team. Having all employees aware of how to respond gives the firm an expanded institutional radar that can lower the chances of being blindsided. This can be especially important as many conversations take place in the so-called dark Web beyond the reach of conventional search engines and monitoring tools (e.g., within membership communities or sites, such as Facebook, where only “friends” have access).

In the event of an incident, silence can be deadly. Consumers expect a response to major events, even if it’s just “we’re listening, we’re aware, and we intend to fix things.” When director Kevin Smith was asked to leave a Southwest Airline flight because he was too large for a single seat, Smith went ballistic on Twitter, berating Southwest’s service to his thousands of online followers. Southwest responded that same evening via Twitter, posting, “I’ve read the tweets all night from @ThatKevinSmith—He’ll be getting a call at home from our Customer Relations VP tonight.”

In the event of a major crisis, firms can leverage online media outside the social sphere. In the days following the Domino’s incident, the gross-out video consistently appeared near the top of Google searches about the firm. When appropriate, companies can buy ads to run alongside keywords explaining their position and, if appropriate, offering an apology (Gregory, 2009). Homeopathic cold remedy Zicam countered blog posts citing inaccurate product information by running Google ads adjacent to these links, containing tag lines such as “Zicam: Get the Facts4.”

Review sites such as Yelp and TripAdvisor also provide opportunities for firms to respond to negative reviews. This can send a message that a firm recognizes missteps and is making an attempt to address the issue (follow-through is critical, or expect an even harsher backlash). Sometimes a private response is most effective. When a customer of Farmstead Cheeses and Wines in the San Francisco Bay area posted a Yelp complaint that a cashier was rude, the firm’s owner sent a private reply to the poster pointing out that the employee in question was actually hard of hearing. The complaint was subsequently withdrawn and the critic eventually joined the firm’s Wine Club (Paterson, 2009) . Private responses may be most appropriate if a firm is reimbursing clients or dealing with issues where public dialogue doesn’t help the situation. One doesn’t want to train members of the community that public griping gets reward. For similar reasons, in some cases store credit rather than reimbursement may be appropriate compensation.

Who Should Speak for Your Firm? The Case of the Cisco Fatty

Using the Twitter handle “TheConnor,” a graduating college student recently offered full-time employment by the highly regarded networking giant Cisco posted this tweet: “Cisco just offered me a job! Now I have to weigh the utility of a fatty paycheck against the daily commute to San Jose and hating the work.” Bad idea. Her tweet was public and a Cisco employee saw the post, responding, “Who is the hiring manager. I’m sure they would love to know that you will hate the work. We here at Cisco are versed in the web.” Snap!

But this is also where the story underscores the subtleties of social media engagement. Cisco employees are right to be stung by this kind of criticism. The firm regularly ranks at the top of Fortune’s list of “Best Firms to Work for in America.” Many Cisco employees take great pride in their work, and all have an interest in maintaining the firm’s rep so that the company can hire the best and brightest and continue to compete at the top of its market. But when an employee went after a college student so publicly, the incident escalated. The media picked up on the post, and it began to look like an old guy picking on a clueless young woman who made a stupid mistake that should have been addressed in private. There was also an online pile-on attacking TheConnor. Someone uncovered the woman’s true identity and posted hurtful and disparaging messages about her. Someone else set up a Web site at CiscoFatty.com. Even Oprah got involved, asking both parties to appear on her show (the offer was declined). A clearer social media policy highlighting the kinds of issues to respond to and offering a reporting hierarchy to catch and escalate such incidents might have headed off the embarrassment and helped both Cisco and TheConnor resolve the issue with a little less public attention (Popkin, 2009).

It’s time to take social media seriously. We’re now deep into a revolution that has rewritten the rules of customer-firm communication. There are emerging technologies and skills to acquire, a shifting landscape of laws and expectations, a minefield of dangers, and a wealth of unexploited opportunities. Organizations that professionalize their approach to social media and other Web 2.0 technologies are ready to exploit the upside—potentially stronger brands, increased sales, sharper customer service, improved innovation, and more. Those that ignore the new landscape risk catastrophe and perhaps even irrelevance.

Key Takeaways

- Customer conversations are happening and employees are using social media. Even firms that aren’t planning on creating a social media presence need to professionalize the social media function in their firm (consider this a social media awareness and response team, or SMART).

- Social media is an interdisciplinary practice, and the team should include professionals experienced in technology, marketing, PR, customer service, legal, and human resources.

- While the social media team provides guidance, training, and oversight, and structures crisis response, it’s important to ensure that authentic experts engage on behalf of the firm. Social media is a conversation, and this isn’t a job for the standard PR-style corporate spokesperson.

- Social media policies revolve around “three Rs”: representation, responsibility, and respect. Many firms have posted their policies online so it can be easy for a firm to assemble examples of best practice.

- Firms must train employees and update their knowledge as technologies, effective use, and threats emerge. Security training is a vital component of establishing social media policy. Penalties for violation should be clear and backed by enforcement.

- While tempting, creating sock puppets to astroturf social media with praise posts violates FTC rules and can result in prosecution. Many users who thought their efforts were anonymous have been embarrassingly exposed and penalized. Customers are also using social media to expose firm dishonesty.

- Many tools exist for monitoring social media mentions of an organization, brands, competitors, and executives. Google Alerts, Twitter search, TweetDeck, Twitrratr, bit.ly, Facebook, and Foursquare all provide free tools that firms can leverage. For-fee tools and services are available as part of the online reputation management industry (and consultants in this space can also provide advice on improving a firm’s online image and engagement).

- Social media are easy to adopt and potentially easy to abuse. The social media team can provide monitoring and support for firm-focused efforts inside the company and running on third-party networks, both to improve efforts and prevent unwanted disclosure, compliance, and privacy violations.

- The embassy approach to social media has firms establish their online presence through consistently named areas within popular services (e.g., facebook.com/starbucks, twitter.com/starbucks, youtube.com/starbucks). Firms can also create their own branded social media sites using tools such as Salesforce.com’s “Ideas” platform.

- Social media provides “four Ms” of engagement: the megaphone to send out messages from the firm, the magnet to attract inbound communication, and monitoring and mediation—paying attention to what’s happening online and selectively engage conversations when appropriate. Engagement can be public or private.

- Engagement is often more art than science, and managers can learn a lot by paying attention to the experiences of others. Firms should have clear rules for engagement and escalation when positive or negative issues are worthy of attention.

Questions and Exercises

- The “United Breaks Guitars” and “Domino’s Gross Out” incidents are powerful reminders of how customers and employees can embarrass a firm. Find other examples of customer-and-employee social media incidents that reflected negatively on an organization. What happened? What was the result? How might these incidents have been prevented or better dealt with?

- Hunt for examples of social media excellence. List an example of an organization that got it right. What happened, and what benefits were received?

- Social media critics often lament a lack of ROI (return on investment) for these sorts of efforts. What kind of return should firms expect from social media? Does the return justify the investment? Why or why not?

- What kinds of firms should aggressively pursue social media? Which ones might consider avoiding these practices? If a firm is concerned about online conversations, what might this also tell management?

- List the skills that are needed by today’s social media professionals. What topics should you study to prepare you for a career in this space?

- Search online to find examples of corporate social media policies. Share your findings with your instructor. What points do these policies have in common? Are there aspects of any of these policies that you think are especially strong that other firms might adopt? Are there things in these policies that concern you?

- Should firms monitor employee social media use? Should they block external social media sites at work? Why or why not? Why might the answer differ by industry?

- Use the monitoring tools mentioned in the reading to search your own name. How would a prospective employer evaluate what they’ve found? How should you curate your online profiles and social media presence to be the most “corporate friendly”?

- Investigate incidents where employees were fired for social media use. Prepare to discuss examples in class. Could the employer have avoided these incidents?

- Use the monitoring tools mentioned in the reading to search for a favorite firm or brand. What trends do you discover? Is the online dialogue fair? How might the firm use these findings?

- Consider the case of the Cisco Fatty. Who was wrong? Advise how a firm might best handle this kind of online commentary.

1The concepts in this section are based on work by J. Kane, R. Fichman, J. Gallaugher, and J. Glasser, many of which are covered in the article “Community Relations 2.0,” Harvard Business Review, November 2009.

2Starbucks was named the best firm for social media engagement in a study by Altimeter Group and WetPaint. See the 2009 ENGAGEMENTdb report at http://engagementdb.com.

3Also available via UStream and DigitalMarketingZen.com.

4Zicam had regularly been the victim of urban legends claiming negative side effects from use; see Snopes.com, “Zicam Warning,” http://www.snopes.com/medical/drugs/zicam.asp. However, the firm subsequently was cited in an unrelated FDA warning on the usage of its product; see S. Young, “FDA Warns against Using 3 Popular Zicam Cold Meds,” CNN.com, June 16, 2009.

References

Barger, C., talk at the Social Media Club of Detroit, November 18, 2009.

Bolton, N., “Foursquare Introduces New Tools for Businesses,” March 9, 2010.

Conway, L., “Virgin Atlantic Sacks 13 Staff for Calling Its Flyers ‘Chavs,’” The Independent, November 1, 2008.

Gallaugher J. and S. Ransbotham, “Social Media and Dialog Management at Starbucks” (presented at the MISQE Social Media Workshop, Phoenix, AZ, December 2009).

Gregory, S., “Domino’s YouTube Crisis: 5 Ways to Fight Back,” Time, April 18, 2009.

Jacques, A., “Domino’s Delivers during Crisis: The Company’s Step-by-Step Response after a Vulgar Video Goes Viral,” The Public Relations Strategist, October 24, 2009.

Kane, J., R. Fichman, J. Gallaugher, and J. Glaser, “Community Relations 2.0,” Harvard Business Review, November 2009.

Martin, A., “Whole Foods Executive Used Alias,” New York Times, July 12, 2007.

Miller, C. C., “Company Settles Case of Reviews It Faked,” July 14, 2009.

Nelson, B., presentation at the Social Media Conference NW, Mount Vernon, WA, March 25, 2010.

Paterson, K., “Managing an Online Reputation,” New York Times, July 29, 2009.

Popkin, H., “Twitter Gets You Fired in 140 Characters or Less,” MSNBC, March 23, 2009.

Rathke, L., “Report: Ski Resorts Exaggerate Snowfall Totals,” USA Today, January 29, 2010.

Schonfeld, E., “Time Magazine Throws Up Its Hands As It Gets Pawned by 4Chan,” TechCrunch, April 27, 2009.

Soat, J., “7 Questions Key to Social Networking Success,” InformationWeek, January 16, 2010.

Stone, B., “Facebook Aims to Extend Its Reach across the Web,” New York Times, December 2, 2008.

York, E., “McDonald’s Names First Social-Media Chief,” Chicago Business, April 13, 2010.