12 9.3 Application Software

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Appreciate the difference between desktop and enterprise software.

- List the categories of enterprise software.

- Understand what an ERP (enterprise resource planning) software package is.

- Recognize the relationship of the DBMS (database system) to the other enterprise software systems.

- Recognize both the risks and rewards of installing packaged enterprise systems.

Operating systems are designed to create a platform so that programmers can write additional applications, allowing the computer to do even more useful things. While operating systems control the hardware, application software (sometimes referred to as software applications, applications, or even just apps) perform the work that users and firms are directly interested in accomplishing. Think of applications as the place where the users or organization’s real work gets done. As we learned in Chapter 6 “Understanding Network Effects”, the more application software that is available for a platform (the more games for a video game console, the more apps for your phone), the more valuable it potentially becomes.

Desktop software refers to applications installed on a personal computer—your browser, your Office suite (e.g., word processor, spreadsheet, presentation software), photo editors, and computer games are all desktop software. Enterprise software refers to applications that address the needs of multiple, simultaneous users in an organization or work group. Most companies run various forms of enterprise software programs to keep track of their inventory, record sales, manage payments to suppliers, cut employee paychecks, and handle other functions.

Some firms write their own enterprise software from scratch, but this can be time consuming and costly. Since many firms have similar procedures for accounting, finance, inventory management, and human resource functions, it often makes sense to buy a software package (a software product offered commercially by a third party) to support some of these functions. So-called enterprise resource planning (ERP) software packages serve precisely this purpose. In the way that Microsoft can sell you a suite of desktop software programs that work together, many companies sell ERP software that coordinates and integrates many of the functions of a business. The leading ERP vendors include the firm’s SAP and Oracle, although there are many firms that sell ERP software. A company doesn’t have to install all of the modules of an ERP suite, but it might add functions over time—for example, to plug in an accounting program that is able to read data from the firm’s previously installed inventory management system. And although a bit more of a challenge to integrate, a firm can also mix and match components, linking software the firm has written with modules purchased from different enterprise software vendors.

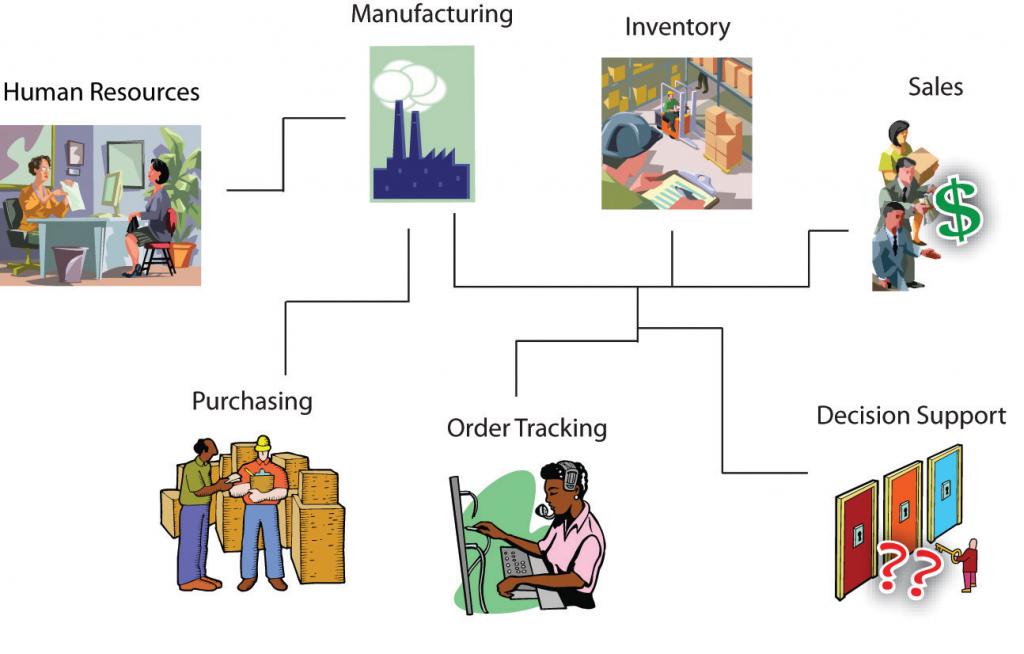

An ERP system with multiple modules installed can touch many functions of the business:

- Sales—A sales rep from Vermont-based SnowboardCo. takes an order for five thousand boards from a French sporting goods chain. The system can verify credit history, apply discounts, calculate price (in euros), and print the order in French.

- Inventory—While the sales rep is on the phone with his French customer, the system immediately checks product availability, signaling that one thousand boards are ready to be shipped from the firm’s Burlington warehouse, the other four thousand need to be manufactured and can be delivered in two weeks from the firm’s manufacturing facility in Guangzhou.

- Manufacturing—When the customer confirms the order, the system notifies the Guangzhou factory to ramp up production for the model ordered.

- Human Resources—High demand across this week’s orders triggers a notice to the Guangzhou hiring manager, notifying her that the firm’s products are a hit and that the flood of orders coming in globally mean her factory will have to hire five more workers to keep up.

- Purchasing—The system keeps track of raw material inventories, too. New orders trigger an automatic order with SnowboardCo’s suppliers, so that raw materials are on hand to meet demand.

- Order Tracking—The French customer can log in to track her SnowboardCo order. The system shows her other products that are available, using this as an opportunity to cross-sell additional products.

- Decision Support—Management sees the firm’s European business is booming and plans a marketing blitz for the continent, targeting board models and styles that seem to sell better for the Alps crowd than in the U.S. market.

Other categories of enterprise software that managers are likely to encounter include the following:

- customer relationship management (CRM) systems used to support customer-related sales and marketing activities

- supply chain management (SCM) systems that can help a firm manage aspects of its value chain, from the flow of raw materials into the firm through delivery of finished products and services at the point-of-consumption

- business intelligence (BI) systems, which use data created by other systems to provide reporting and analysis for organizational decision making

Major ERP vendors are now providing products that extend into these and other categories of enterprise application software, as well.

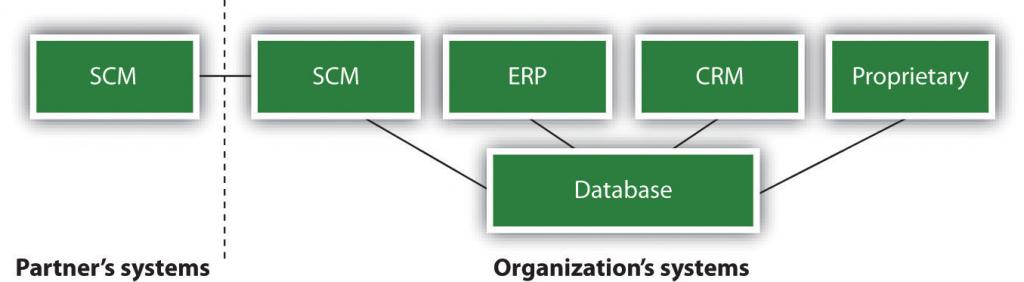

Most enterprise software works in conjunction with a database management system (DBMS), sometimes referred to as a “database system.” The database system stores and retrieves the data that an application creates and uses. Think of this as another additional layer in our cake analogy. Although the DBMS is itself considered an application, it’s often useful to think of a firm’s database systems as sitting above the operating system, but under the enterprise applications. Many ERP systems and enterprise software programs are configured to share the same database system so that an organization’s different programs can use a common, shared set of data. This system can be hugely valuable for a company’s efficiency. For example, this could allow a separate set of programs that manage an inventory and point-of-sale system to update a single set of data that tells how many products a firm has to sell and how many it has already sold—information that would also be used by the firm’s accounting and finance systems to create reports showing the firm’s sales and profits.

Firms that don’t have common database systems with consistent formats across their enterprise often struggle to efficiently manage their value chain. Common procedures and data formats created by packaged ERP systems and other categories of enterprise software also make it easier for firms to use software to coordinate programs between organizations. This coordination can lead to even more value chain efficiencies. Sell a product? Deduct it from your inventory. When inventory levels get too low, have your computer systems send a message to your supplier’s systems so that they can automatically build and ship replacement product to your firm. In many cases these messages are sent without any human interaction, reducing time and errors. And common database systems also facilitate the use of BI systems that provide critical operational and competitive knowledge and empower decision making. For more on CRM and BI systems, and the empowering role of data, see Chapter 11 “The Data Asset: Databases, Business Intelligence, and Competitive Advantage”.

Figure 9.5

An organization’s database management system can be set up to work with several applications both within and outside the firm.

The Rewards and Risks of Packaged Enterprise Systems

When set up properly, enterprise systems can save millions of dollars and turbocharge organizations. For example, the CIO of office equipment maker Steelcase credited the firm’s ERP with an eighty-million-dollar reduction in operating expenses saved from eliminating redundant processes and making data more usable. The CIO of Colgate Palmolive also praised their ERP, saying, “The day we turned the switch on, we dropped two days out of our order-to-delivery cycle” (Robinson & Dilts, 1999). Packaged enterprise systems can streamline processes, make data more usable, and ease the linking of systems with software across the firm and with key business partners. Plus, the software that makes up these systems is often debugged, tested, and documented with an industrial rigor that may be difficult to match with proprietary software developed in-house.

But for all the promise of packaged solutions for standard business functions, enterprise software installations have proven difficult. Standardizing business processes in software that others can buy means that those functions are easy for competitors to match, and the vision of a single monolithic system that delivers up wondrous efficiencies has been difficult for many to achieve. The average large company spends roughly $15 million on ERP software, with some installations running into the hundreds of millions of dollars (Rettig, 2007). And many of these efforts have failed disastrously.

FoxMeyer was once a six-billion-dollar drug distributor, but a failed ERP installation led to a series of losses that bankrupted the firm. The collapse was so rapid and so complete that just a year after launching the system, the carcass of what remained of the firm was sold to a rival for less than $80 million. Hershey Foods blamed a $466 million revenue shortfall on glitches in the firm’s ERP rollout. Among the problems, the botched implementation prevented the candy maker from getting product to stores during the critical period before Halloween. Nike’s first SCM and ERP implementation was labeled a “disaster”; their systems were blamed for over $100 million in lost sales (Koch, 2004). Even tech firms aren’t immune to software implementation blunders. HP once blamed a $160 million loss on problems with its ERP systems (Charette, 2005). Manager beware—there are no silver bullets. For insight on the causes of massive software failures, and methods to improve the likelihood of success, see Section 9.6 “Total Cost of Ownership (TCO): Tech Costs Go Way beyond the Price Tag”.

Key Takeaways

- Application software focuses on the work of a user or an organization.

- Desktop applications are typically designed for a single user. Enterprise software supports multiple users in an organization or work group.

- Popular categories of enterprise software include ERP (enterprise resource planning), SCM (supply chain management), CRM (customer relationship management), and BI (business intelligence) software, among many others.

- These systems are used in conjunction with database management systems, programs that help firms organize, store, retrieve, and maintain data.

- ERP and other packaged enterprise systems can be challenging and costly to implement, but can help firms create a standard set of procedures and data that can ultimately lower costs and streamline operations.

- The more application software that is available for a platform, the more valuable that platform becomes.

- The DBMS stores and retrieves the data used by the other enterprise applications. Different enterprise systems can be configured to share the same database system in order share common data.

- Firms that don’t have common database systems with consistent formats across their enterprise often struggle to efficiently manage their value chain, and often lack the flexibility to introduce new ways of doing business. Firms with common database systems and standards often benefit from increased organizational insight and decision-making capabilities.

- Enterprise systems can cost millions of dollars in software, hardware, development, and consulting fees, and many firms have failed when attempting large-scale enterprise system integration. Simply buying a system does not guarantee its effective deployment and use.

- When set up properly, enterprise systems can save millions of dollars and turbocharge organizations by streamlining processes, making data more usable, and easing the linking of systems with software across the firm and with key business partners.

Questions and Exercises

- What is the difference between desktop and enterprise software?

- Who are the two leading ERP vendors?

- List the functions of a business that might be impacted by an ERP.

- What do the acronyms ERP, CRM, SCM, and BI stand for? Briefly describe what each of these enterprise systems does.

- Where in the “layer cake” analogy does the DBMS lie.

- Name two companies that have realized multimillion-dollar benefits as result of installing enterprise systems.

- Name two companies that have suffered multimillion-dollar disasters as result of failed enterprise system installations.

- How much does the average large company spend annually on ERP software?

1Adapted from G. Edmondson, “Silicon Valley on the Rhine,” BusinessWeek International, November 3, 1997.

References

Charette, R., “Why Software Fails,” IEEE Spectrum, September 2005.

Koch, C., “Nike Rebounds: How (and Why) Nike Recovered from Its Supply Chain Disaster,” CIO, June 15, 2004.

Rettig, C., “The Trouble with Enterprise Software,” MIT Sloan Management Review 49, no. 1 (2007): 21–27.

Robinson A. and D. Dilts, “OR and ERP,” ORMS Today, June 1999.