30 “A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning” (1633)

with an Introduction by Rebecca Rhoades

John Donne

Introduction: Distance and Death in John Donne’s “A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning”

When contextualizing the works of verse that exist within the realm of metaphysical poetry, the influence and impact of John Donne is not only primary, but unavoidable. This genre of poetry operates upon philosophical manipulations of language, “frequently employing unexpected similes and metaphors in displays of wit,” according to The Poetry Foundation. Donne’s style is also influenced greatly by his religion, which he struggled with throughout his life as he was born into a Catholic family and later converted to Anglicanism and became a prominent priest in the Church of England. Of Donne’s works published in his lifetime, most were related to religious pursuits, such as devotions, sermons and meditations. Some of his early love poetry and other works circulated in manuscript form during his life, but only among his friends and others he chose to share them with. His love poetry was published posthumously, most likely against his wishes. Donne was evidently deeply self-aware, stemming from his attentiveness to the understandings of the soul. Donne blends aspects of religious verse into his love poems and vice versa, which essentially disallows any of his works from being strictly defined as love poems or religious poems.

Donne’s love for his wife, Anne More, was clearly present in his life. They had to marry in secret as he knew he would not obtain the blessing of Anne’s father, Sir George More. Because of this, Donne was unable to find a job or make money to support his family. He lived modestly, depending on friends, until he took his holy orders and eventually became a dean at St. Paul’s Cathedral. Unfortunately, Anne tragically passed away after giving birth to a stillborn child in 1617, only two years after Donne found status in the Church.

The poem “A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning” was published in 1633 in Songs and Sonnets. It was published two years after Donne’s death, but was most likely written around 1611 before Donne’s departure on a trip throughout Europe. In this poem, Donne’s fascination with death emerges, representing his own insecurities and fears around mortality. Donne loved and obsessed over death in his art because of its allure and suspense; to him, it is “challenging, not mournful” and “almost never sad, and never simply sad,” according to John Carey in his book, John Donne, Life, Mind, and Art (203). Donne understood that we already know what it is to live, but death is interesting because of its uncertainty and how it leaves much to be manipulated by the imagination. So, with an incredibly active and vivid imagination, the metaphysical poet was able to draw many comparisons between worldly imagery to philosophical or religious concepts. This poem creates a link between a difficult farewell between lovers and the reality of death. This connection allows for multiple readings or understandings of this poem, further encapsulating its meaning, which points to a cyclical pattern of death, or a lover’s goodbye.

“A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning” Text

As virtuous men pass mildly away,

And whisper to their souls to go,

Whilst some of their sad friends do say,

“Now his breath[1] goes,” and some say, “No.”

So let us melt[2], and make no noise,

No tear-floods, nor sigh-tempests move;

’Twere profanation of our joys

To tell the laity our love.

Moving of th’ earth brings harms and fears;

Men reckon what it did, and meant;

But trepidation of the spheres,

Though greater far, is innocent.

Dull sublunary lovers’ love

—Whose soul is sense—cannot admit

Of absence, ’cause it doth remove

The thing which elemented it.

But we by a love so much refined,

That ourselves know not what it is,

Inter-assurèd of the mind,

Care less, eyes, lips and hands to miss.

Our two souls therefore, which are one,

Though I must go, endure not yet

A breach, but an expansion,

Like gold to aery thinness beat.

If they be two, they are two so

As stiff twin compasses[3] are two;

Thy soul, the fix’d foot, makes no show

To move, but doth, if th’ other do.

And though it in the centre sit,

Yet, when the other far doth roam,

It leans, and hearkens after it,

And grows erect, as that comes home.

Such wilt thou be to me, who must,

Like th’ other foot, obliquely run;

Thy firmness makes my circle just

And makes me end where I begun[4].

Sources:

“A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning” [PDF] edited by Bonnie J. Robinson, Ph.D. and Laura J. Getty, Ph.D. from British Literature: Middle Ages to the Eighteenth Century and Neoclassicism [PDF] is licensed by CC BY-SA

Baskin, Leonard. John Donne in His Winding Cloth. 1955. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC. The Smithsonian Institution, books.google.com/books?id=40EEAAAAMBAJ&lpg=PA87&dq=Baskin%20John%20Donne%20in%20His%20Winding%20Cloth&pg=PA87#v=onepage&q=Baskin%20John%20Donne%20in%20His%20Winding%20Cloth&f=false.

Carey, John. John Donne, Life, Mind, and Art. New York, OUP, 1981, archive.org/details/johndonnelifemin0000care/page/208/mode/2up.

Davies, Peter. “Congé.” The New Oxford Companion to Literature in French. : Oxford University Press, , 2005. Oxford Reference. https://doi.org/10.1093/acref/9780198661252.001.0001.

Doebler, John. “A Submerged Emblem in Sonnet 116.” Shakespeare Quarterly, vol. 15, 1964, jstor.org/stable/2867968.

Donne, John. “A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning.” Luminarium, 1896, luminarium.org/sevenlit/donne/mourning.php.

Donne, John. Biathanatos [PDF], edited by Michael Rudick and M. Pabst Battin, Garland Publishing, 1982, web.archive.org/web/20111117203143/http://www.philosophy.utah.edu/onlinepublications/PDFs/Biathanatos_CompleteText.pdf.

Donne, John, and Gary A. Stringer. The Variorum Edition of the Poetry of John Donne, vol 8. Indiana University Press, 1995.

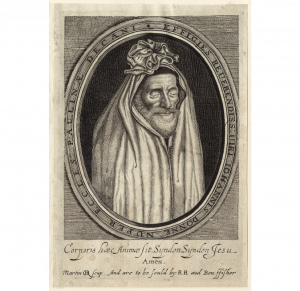

Droeshout, Martin. John Donne. 1633. National Portrait Gallery, London, England. npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw128952/John-Donne?LinkID=mp01330&search=sas&sText=John+Donne&role=sit&rNo=3.

Freccero, John. “Donne’s ‘Valediction: Forbidding Mourning.’” ELH, vol. 30, 1963. https://doi.org/10.2307/2871909.

Jahn, J. D. “The Eschatological Scene of Donne’s ‘A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning.’” College Literature, 1978. jstor.org/stable/25111197.

“John Donne.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 17 Apr. 2021, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Donne.

“Metaphysical Poets.” The Poetry Foundation. 2021, www.poetryfoundation.org/education/glossary/metaphysical-poets.

“Melt, V. (1), Sense 6.” Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford UP, September 2025, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/3423457824.

“Melt, V. (1), Sense 3.b.” Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford UP, September 2025, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/3726843039.

Pinka, Patricia Garland. “John Donne”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 12 Nov. 2025, www.britannica.com/biography/John-Donne.

The Bible. 21st Century King James Version. Deuel Enterprises, Inc., 1994.

How to Cite this Chapter:

Donne, John. “A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning.” Transatlantic Literature and Premodern Worlds, edited by Marissa Nicosia, et al., Pressbooks, 2025.

Rhoades, Rebecca. “Distance and Death in John Donne’s ‘A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning.'” Transatlantic Literature and Premodern Worlds, edited by Marissa Nicosia, et al., Pressbooks, 2025.

- Donne starts the poem with imagery related to one of his deepest fascinations: death. The “breath” that represents the dying man’s last is complimentary to the Christian creation doctrine, in which God created man and “breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living soul” (21st Century King James Bible, Gen. 2:7). Even further, this breath can be compared to the idea of the pneuma, or spiritus – “the mysterious substance which was considered to be the medium of the soul’s action on the body, as well of the medium of the planetary’s soul action on the heavenly body” (Freccero 357). This belief in pneumatic breath is reflective of teachings that Donne had learned that reference the cyclical pattern of a soul’s existence in the human body. John Carey states that Donne was attracted to death and writing about it because “its insertion into poems, secular or divine, can help to make them urgent and momentous as [he] needs them to be” (207). So even if Donne harbored inner insecurities about death that fed his fascination, he depicted death as something enviable and “more dynamic than life” (Carey 203). Donne’s need to create a spectacle of death extended even to his own; near the end of his life when he thought he was dying, he arranged for a portrait of himself to be drawn in his old, decaying state. According to his biographer, Donne undressed himself and draped his body with linen, and then got into an urn; “this drawing of himself as a corpse was then hung by his bed, to remind him what the future held, and to exhibit the courage and virtuosity with which he was facing it” (Carey 214). Figure 1 depicts an engraving done for a 1632 publication of Donne’s last sermon, Death’s Duel. This engraving was based on the previously mentioned drawing of Donne draped in a shroud. ↵

- Even considering the removal of all science related entries, the OED has compiled many definitions for the word “melt.” As a verb, it can be defined as “to weaken, to reduce in strength or vitality” (“melt, v. (1), sense 6”). However, another definition listed in the OED may more accurately explain the way in which Donne uses the word ‘melt’ here, defined as, “to become softened by compassion, pity, love, etc.; to yield to entreaty” (“melt, v. (1), sense 3b”) Donne’s speaker implores his lover to not react mournfully in response to events like death or even in times of their separation from one another. This moment of redirection is an example of a conge d’amour, a French term that depicts a “farewell to love in general or to an unforthcoming lady in particular without going so far as indicat[ing] preference for a new mistress” (Congé). Taken as a whole, “So let us melt” represents a disruption and separation from the previous image of death. It works on two levels, as it can be applied to either understanding of the poem. The speaker redirects his lover from thinking about the deceased man, as the image itself never resurfaces again in the poem, to the conge d’amour in which the speaker needs to convince his lover that goodbye is not so bad, and it is not necessarily an end. ↵

- During Donne’s time, imagery that included a depiction of a drawing compass implied some cyclical pattern or circular imagery. This usage is seen not just in Donne’s poetry, but also in William Shakespeare’s “Sonnet 116” where the “emphasis is upon the contrasting symbolism of the legs in the compass” (Doebler 110). In both poems, there is a mobile foot and an immobile, “fixed” one, accurately representing a compass’s features. The feet of the compass can apply to the two lovers – the one who must stay and the one who is saying goodbye – or to the idea of death and its cyclical tendency of “both completion and reunion” (Jahn 40). Something that separates Donne from other poets or religious writers is his beliefs about death, specifically suicide. He wrote one of the first ever English defenses of suicide, Biathanatos. In this work, Donne considers the relationship between church doctrine and individual choice. Donne’s most contentious claim in the text is that Christ’s death itself was an act of suicide. Donne understands life as a cyclical process of both birth and death, in which death is necessary to bring about the continuation of life. Donne argues in Biathanatos that because of this necessity, death at the hand of oneself progresses along the circle, continuing according to a predetermined plan, in the same way Jesus needed to die in order complete God’s prophetical plan and cyclical process of death and resurrection. Donne’s sentiment for death has become a part of his lasting legacy, as seen in Figure 2 which is a sculpture of Donne created in the twentieth century, and it depicts him draped in taut linens to represent the sickly image he had drawn of himself that was shown in Figure 1. This sculpture was part of a collection by Leonard Baskin, who was featured in an edition of Life Magazine in 1957 in a section titled “Images of Mortality.” ↵

- By ending where the speaker began, the poem makes its final revelation about the cyclical pattern of death. Donne shows how death is a marker of beginning and end as the poem begins. Death, dually represented in the poem as also a valediction for a lover, suggests the possibility of the speaker becoming one of the “virtuous men” of the poem’s first line. John Freccero, says in his critique “Donne’s ‘Valediction: Forbidding Mourning’” that “the epigrammatic quality of the last verse suggests that the harmonization of the circle and the line is indeed complete and that both motions end at their point of departure” (340). The link between the cyclical pattern of death and the lover’s goodbye is strengthened. If the speaker truly ends where he begins, then he will end in the same way the poem itself began – on his deathbed. Each stanza after the first stems farther away from death, as the speaker talks about distance and how it could never affect the couple’s genuine and other-worldly love, until the final stanza finishes the cyclical pattern by returning the reader to the poem’s point of origin. The poem outlines the possible trials of distance, but Donne’s speaker instead boasts that his love can conquer even the most difficult trials of all: death. The poem’s references to love and commitment despite distance reflect the strong relationship between John Donne and his own spouse, Anne. After her tragic death in 1617, “Donne vowed to never marry again” according to his biography in Britannica. Donne never loved anyone else, proving the strength of his beliefs that he expresses in this poem. “A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning” showcases Donne’s complex understanding of death while also suggesting that his relationship and love for his wife was one thing that could be more powerful than absence or distance, and possibly even death itself. ↵