33 “A World in an Earring”

With an Introduction by Kaine Connelly Seif and a Student at Penn State University

Margaret Cavendish

Introduction

Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, was a seventeenth-century English poet and philosopher known for her poetry and prose that delved into scientific, religious, and philosophical topics. She was “one of the more prolific authors in early modern print” and wrote within a variety of genres including scientific treatises, plays, romance, and science fiction (Walters 4). Her work “demonstrates a profound engagement with, and radical critique of, her intellectual and cultural milieu” and reading her works can help modern audiences gain a nuanced and unique perspective on English affairs and Enlightenment thinking (4).

Cavendish was born into a large family as Margaret Lucas. The Lucases were detested by their fellows in Essex, due in part to their support of Charles I as royalists and their arguably antagonistic financial practices, including cutting off the town water supply (15-16). Ultimately, their unpopular standing led to mob violence directed toward them in which their home was plundered. Later, against the advice of her family, Cavendish became a member of the French queen consort Henrietta Maria’s court. It was in France that she met William Cavendish, the Marquis of Newcastle, and the two married and weathered political exile together as former supporters of Charles I (17).

Cavendish is a figure of note when it comes to scientific and philosophical subjects. She was the first woman invited to a session of the Royal Society, a learned scientific society dedicated to improving and expanding scientific knowledge. Cavendish was an advocate for theories of materialism, arguing that all beings were made of self-moving, rational matter (“Margaret Cavendish”). Throughout her expansive body of work, “Cavendish continued to express an interest in mixing science and more imaginative mediums of literature” (Walters 24). Her poem “A World in an Earring” is a blend of her poetic prowess and personal ideas, showcasing her literary style and her capability for philosophical thought in one mesmerizing piece.

“A World in an Earring”

An earring round may well a zodiac[1] be,

Wherein a sun goes round, which we don’t see;

And planets seven about that sun may move,

And he stand still, as learnèd men would prove;

And fixèd stars like twinkling diamonds, placed 5

About this earring, which a world is vast.

That same which doth the earring hold, the hole,

Is that we call the North and Southern Pole;

There nipping frosts may be, and winters cold,

Yet never on the lady’s ear take hold. 10

And lightning, thunder, and great winds may blow

Within this earring, yet the ear not know.

Fish there may swim in seas, which ebb and flow,

And islands be, wherein do spices grow[2];

There crystal rocks hang dangling at each ear, 15

And golden mines as jewels may they wear.

There earthquakes be, which mountains vast down fling,

And yet ne’er stir the lady’s ear, nor ring.

There meadows be, and pastures fresh and green,

And cattle feed, and yet be never seen, 20

And gardens fresh, and birds which sweetly sing,

Although we hear them not in an earring.

There night and day, and heat and cold, and so

May life and death, and young and old still grow.

Thus youth may spring, and several ages die; 25

Great plagues may be, and no infections nigh[3].

There cities be, and stately houses built,

Their inside gay, and finely may be gilt.

There churches be, wherein priests teach and sing,

And steeples too, yet hear the bells not ring. 30

From thence may pious tears to Heaven run,

And yet the ear not know which way they’re gone.

There markets be, where things are bought and sold,

Though th’ear knows not the price their markets hold.

There governors do rule, and kings do reign, 35

And battles fought, where many may be slain.

And all within the compass of this ring,

Whence they no tidings to the wearer bring.

Within the ring, wise counsellors may sit,

And yet the ear not one wise word may get. 40

There may be dancing all night at a ball,

And yet the ear be not disturbed at all.

There rivals duels fight, where some are slain;

There lovers mourn, yet hear them not complain.

And Death may dig a lover’s grave: thus were 45

A lover dead in a fair lady’s ear.

But when the ring is broke, the world is done;

Then lovers they into Elysium run[4].

Sources:

“A World in an Earring” edited by Liza Blake from Margaret Cavendish’s Poems and Fancies licensed by CC BY-NC

“Elysium, N., Sense 1.” Oxford English Dictionary, OUP, July 2023, doi.org/10.1093/OED/2633427808.

“Elysium, N., Sense 2.” Oxford English Dictionary, OUP, July 2023, doi.org/10.1093/OED/8511900437.

“Elysium, N., Sense 3.” Oxford English Dictionary, OUP, July 2023, doi.org/10.1093/OED/1108319146.

Totaro, Rebecca. “Fly from that Pestilent Destruction’: Plague in the Works of Margaret Cavendish.” In-Between: Essays and Studies in Literary Criticism, vol 9 no. 1-2, 2000, pp. 117-123.

Walters, Lisa. Margaret Cavendish: Gender, Science, and Politics. Cambridge UP, 2014.

Citations:

Cavendish, Margaret. “A World in an Earring.” Transatlantic Literature and Premodern Worlds, edited by Marissa Nicosia, et al., Pressbooks, 2025.

Seif, Kaine Connelly and a Student at Penn State University. Introduction to Margaret Cavendish’s “A World in an Earring.” Transatlantic Literature and Premodern Worlds, edited by Marissa Nicosia, et al., Pressbooks, 2025.

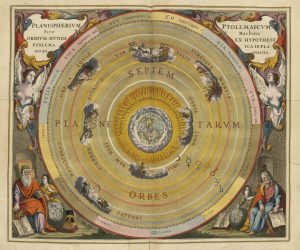

- Astrology was a popular practice even in the early modern period, as philosophers broke from antiquity and “rediscovered” Hermetic and Neoplatonic ideals (Dominici). Cavendish may have been considering astrological questions and examining the zodiac, as “astrological teachings helped to answer philosophical and existential questions” (Dominici). Astrology also played into early modern society even for non-philosophers; the common person had access to zodiacal knowledge through astrologers working as consultants as well as almanacs used to predict weather and best farming practices (Dominici). Figure 1 shows a Renaissance imagining of the universe, positioning the Earth within a larger universe. This is something that Cavendish addresses on several levels in “A World in an Earring” by not only writing about a miniscule world, but by immediately mentioning the zodiac, thus gesturing to a broader universe and an understanding of Earth’s position in this system. ↵

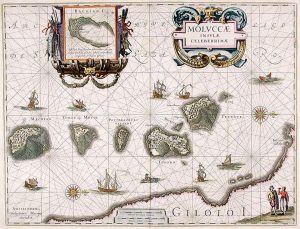

- The Maluku Islands, also called the Moluccas, are located in Indonesia and were known as the “Spice Islands” during the height of European colonization. These islands served as resources for spices like nutmeg, mace, and cloves for the Portuguese, Dutch, and beyond during Cavendish’s time (“Maluku Islands”). It is possible that Cavendish is referring to these islands here, indicating that even in this imagined world, forces like colonization are at play. Even if she is not referring specifically to the “Spice Islands,” Cavendish notes that spices come from other places, other islands, and that very notion links this line with colonization efforts when situated within the context of the British Empire. Figure 2 shows a Renaissance mapping of the “spice islands” from the Atlantis appendix of 1630. ↵

- Rebecca Totaro explains that when Cavendish was writing this poem, “plague had been quiet in the western world for a quarter of a century.” However, “fear and rumour kept its name circulating nevertheless and this may be one reason why Cavendish includes the plague in a world where she might have imagined it did not exist” (Totaro 118). It is unfortunate, however reflective of the times, that Cavendish would not be able to extricate notions of plague from even a world that she was imagining, especially one so mythical and impossible as one contained within an earring. Totaro suggests that while Cavendish was a pioneer in utopian and scientific thought, the limitations she expresses in her various writings on plague (it featured into all twelve of her non-dramatic texts) show that even she was a product of her milieu and the plague-induced anxiety during the early modern period (Totaro). ↵

- According to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), Elysium can reference “the supposed state or abode of the blessed after death in Greek mythology” and well as “any similarly-conceived abode or state of the departed.” These definitions coincide well with the way in which Cavendish utilizes “Elysium” in this poem. The end of the poem discusses a collapsing of the world within an earring, indicating that its inhabitants may either need a new world to inhabit – or they may perish. The idea of the world’s inhabitants moving to a new location fits well with another definition, a figurative one: “A place or state of ideal or perfect happiness.” While the ending of this poem is ambiguous in terms of whether or not the inhabitants die or find a new world to live in, Elysium nevertheless is an appropriate place for Cavendish to next situate them ↵