41 “To his Coy Mistress” (1681)

With an Introduction by Joseph A. Handlin

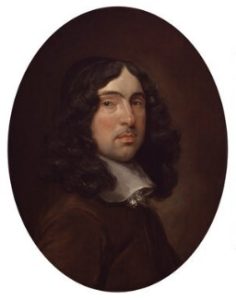

Andrew Marvell

Introduction

Andrew Marvell was born on the 31st of March, 1621, in Yorkshire. In September of 1624, when he was three years old, his family moved to Hull, one of the most important ports in northern England. He lived in Hull for seventeen years. He spent five years developing poetry skills in university at Trinity College, Cambridge. After increasing violence led to a civil war, Marvell spent the next four years and his limited resources “pass[ing] four years in Holland, France, Italy, and Spain ‘to very good purpose, as I beleeve & the gaining of those 4 languages’” (“Marvell”).

In 1659, Marvell was elected to Parliament to represent Hull. His beliefs were described as follows:

The safest reading of his politics in the 1650s is probably that he was prepared to accept any government that would operate within a constitutional framework, and that his admiration of Cromwell was conditional on his remaining ‘still in the Republick’s hand’ (“Marvell.”)

Andrew Marvell passed in 1678. While mourning her loss, his wife Mary Marvell went through her husband’s remaining drafts, and in 1680 sent them to be published with the following message: “Printed according to the exact Copies of my late dear Husband, under his own Hand-Writing” (“Marvell”). Robert Boulter, publisher of Milton’s Paradise Lost, was a good friend of Marvell and published his posthumous works in 1681.“To His Coy Mistress” was included in this edition and it has since s inspired writers with its powerful verse, prompting allusions in works by Terry Pratchett and Stephen King, among others (“To His Coy Mistress”). He kept governing bodies accountable, even if it meant getting in a few fights with his opponents. He often employed his honed poetry skills despite the possibility of “a threat made against his life if he should publish any further ‘Lie or Libel’ against his opponent.” However, “the verdict of contemporaries was that the ‘victory lay on Marvell’s side.” His scathing commentary was so enjoyable that “we still read Marvel’s Answer to Parker with Pleasure” (“Marvell”).

“To his Coy Mistress” Text

Had we but World enough, and Time[1],

This coyness, lady, were no crime.

We would sit down, and think which way

To walk, and pass our long Loves Day.

Thou by the Indian Ganges’ side

Should’st rubies find: I by the tide

Of Humber would complain[2]. I would

Love you ten years before the flood:

And you should, if you please, refuse

Till the conversion of the Jews.

My vegetable Love should grow[3]

Vaster than empires, and more slow;

An hundred years should go to praise

Thine eyes, and on thy forehead gaze,

Two hundred to adore each breast,

But thirty thousand to the rest,

An age at least to every part,

And the last Age should show your Heart.

For, lady, you deserve this state,

Nor would I love at lower rate.

But at my back I always hear

Times winged chariot hurrying near;

And yonder all before us lie

Deserts of vast Eternity.

Thy Beauty shall no more be found,

Nor, in thy marble vault, shall sound

My echoing song; then worms shall try

That long preserved virginity:

And your quaint honor turn to dust:

And into ashes all my lust;

The grave’s a fine and private place,

But none, I think, do there embrace.

Now therefore, while the youthful hue

Sits on thy skin like morning dew,

And while thy willing soul transpires

At every pore with instant fires,

Now let us sport us while we may;

And now, like amorous birds of prey,

Rather at once our Time dev out,

Than languish in his slow-chapped power.

Let us roll all our strength, and all

Our sweetness up into one ball

And tear our pleasures with rough strife,

Through the iron gates of life:

Thus, though we cannot make our sun

Stand still, yet we will make him run[4].

Sources:

“To his Coy Mistress” [PDF] edited by Bonnie J. Robinson, Ph.D. and Laura J. Getty, Ph.D. from British Literature: Middle Ages to the Eighteenth Century and Neoclassicism [PDF] is licensed by CC BY-SA

Citations:

Handlin, Joseph A. Introduction to Andrew Marvell’s “To his Coy Mistress.” Transatlantic Literature and Premodern Worlds, edited by Marissa Nicosia, et al., Pressbooks, 2025.

Marvell, Andrew. “To his Coy Mistress.” Transatlantic Literature and Premodern Worlds, edited by Marissa Nicosia, et al., Pressbooks, 2025.

- “World enough and Time,” is a phrase often debated by scholars including Alex Garganigo, who explains that Marvell’s influence in science fiction using a common science fiction idea – nuclear isotopes: If texts and authors have a Nachleben or afterlife, it seems appropriate in the nuclear age to consider their half-lives, full-lives, and even quarter-lives in SF (science fiction). Category 1 consists of quarter-lives: stories quoting Marvell in paratexts such as titles and epigraphs but nowhere else. Garganigo goes on to explain that “Category 2 consists of Marvell’s half-lives: modest engagement involving in-text quotation advertising “TCM [To his Coy Mistress]” as a prominent narrative element,” while Category 3 includes “extended, meaningful, self-advertised quotation[s] and examination[s] of Marvell’s poem and of Marvell himself.” Where does this quote often find itself though? Garganigo’s findings stated “Most of them (25) quote a phrase from it in their titles. Of those twenty-five, most (17) feature some variant of ‘world enough and time.’” So, most of these works don’t engage much with Marvell’s work despite their titles. This indicates that Marvell’s works are malleable and have a broad cultural impact – one that can fit into this specific genre of fiction despite his existence so long before contemporary publishing and genre breakdowns. ↵

- The Humber Estuary is a body of water near the port city of Hull, where Andrew Marvell initially lived for many years in his youth. It was in this time that his father drowned in the estuary when Andrew Marvell was nineteen in January of 1641. Hull, and the Humber Estuary more specifically, are significant to Marvell’s own life and family trauma and his mention of “Humber” in this poem is not merely coincidental. He expresses his desire to be far from the place where his father died, instead wanting to be by the Ganges instead since there are “...Rubies [to] find...” However, he lived in Hull or another thirty-one years and even died there. ↵

- “Vegetable love” is another way to refer to a slow-growing kind of love. I interpreted that the line is a quite literal interpretation of how plants grow slowly but steadily. In my head, I had an image of two sturdy oaks supporting each other while I read this line. It probably was not any kind of knowledge in the seventeenth century, but we know today that trees can live for thousands of years. Even in those times, Marvell must have been aware that plants had a lot more longevity than animals or even humans. Others have interpreted Vegetable Love much differently. Patrick G. Hogan, who wrote a paper on the subject titled “Marvell's ‘Vegetable Love,’” had this to say regarding the topic: The common misunderstanding of “vegetable Love” is a typical example of how Marvell is misread. “Vegetable” had much stronger metaphysical than culinary associations in the seventeenth century, as in the phrase “vegetable soul” or Milton's “vegetable gold” even. The nearest modern equivalent is perhaps “sentient.” (Hogan 3) This quote mentions a couple of different ways to interpret Vegetable Love, but the most interesting way is sentience, through which Hogan argues that love is alive. Disregarding sexual overtones, this could be a way to say that love has taken on a life of its own. With sexual overtones like “Thine Eyes, and on thy Forehead Gaze. Two hundred to adore each Breast” in mind, perhaps it could be the creation of a family tree through sexual reproduction. ↵

- The line alludes to the idea of “carpe diem,” which means to seize the day, or to go out and make the most of the day while not letting opportunities pass by. This line is what brings me back romantically to this poem after all of the sexual overtones. “We are going to love each other until there is no sun,” is essentially what is being said here, and this kind of sentiment is one I express often with my partner – and if that is not love, I don’t know what is. ↵