46 “The Author to Her Book”(1650)

With an Introduction by Deven Lazovsky and Fernando Trejo

Anne Bradstreet

Introduction

Bradstreet’s work showcased her life as a mother and her relationship to motherhood. In “The Author to Her Book,” she writes about her book The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung Up in America as if writing about her own offspring. However, her relationship with her book seems to have its ups and downs. Throughout her poem, Bradstreet appears to battle between her own passion for writing and her spiritual beliefs, leading to her insulting herself and her work. As a Puritan woman, she was not allowed to showcase her work as something she was proud of, and some scholars have said that her insults toward her book were not genuine. These insults can also be read as an exercise in humility, which was popular amongst writers at this time and was a tenet of her Puritan faith as well (Ball). We can assume that her put-downs were not authentic because Bradstreet had a variety of published and non-published works, and in her non-published works, there were no put-downs of her poetry, suggesting that this may have been implemented in published works to save face (Margerum).

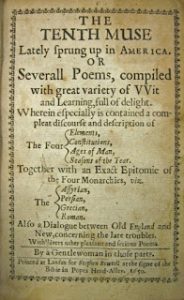

The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung Up in America was originally published in 1650 and is the only of Bradstreet’s works published during her lifetime. It was republished in 1678, six years after her passing, with additional works that were not in the original edition, including “The Author to Her Book.” The work consists of Bradstreet’s anguish over her not being good enough to be presented in front of the mass audience and critics alike. Bradstreet expresses regret over presenting her work, which she refers to as her child, to the public through the publication of The Tenth Muse.” Bradstreet, representing herself as the mother of this child, laments that she has birthed such an unfit child, and chastises herself over the child’s defects. Bradstreet lays forth the remorse, anxieties and fears she had about the publication of her work through this extended metaphor. She addresses all the negative feelings that are within her and the resentment she has about her publication. She deems it a defective child that she attempted to clean up, to correct its defects, though all her efforts prove fruitless. Bradstreet, as its mother, acknowledges that she cannot rid the child of the flaws she bestowed upon it, and with that there is no going back. Her metaphorical child has been exposed to the light, and Bradstreet, although ashamed of herself, must come to terms with that reality.

“The Author to Her Book”

Thou ill-form’d offspring of my feeble brain[1],

Who after birth did’st by my side remain,

Till snatcht from thence by friends, less wise than true[2],

Who thee abroad expos’d to public view[3],

Made thee in rags, halting to th’ press to trudge,

Where errors were not lessened (all may judge).

At thy return my blushing was not small,

My rambling brat (in print) should mother call.

I cast thee by as one unfit for light[4],

Thy Visage was so irksome in my sight[5],

Yet being mine own, at length affection would

Thy blemishes amend, if so I could.

I wash’d thy face, but more defects I saw,

And rubbing off a spot, still made a flaw.

I stretcht thy joints to make thee even feet,

Yet still thou run’st more hobbling than is meet.

In better dress to trim thee was my mind,

But nought save home-spun Cloth, i’ th’ house I find.

In this array, ‘mongst Vulgars mayst thou roam.

In Critics’ hands, beware thou dost not come,

And take thy way where yet thou art not known.

If for thy Father askt, say, thou hadst none;

And for thy Mother, she alas is poor,

Which caus’d her thus to send thee out of door[6].

Source:

“The Author to Her Book” edited by Dr. Robin DeRosa from The Open Education Anthology of Earlier American Literature licensed by CC BY

Margerum, Eileen. “Anne Bradstreet’s Public Poetry and the Tradition of Humility.” Early American Literature, vol. 17, no. 2, 1982, pp. 152–60, JSTOR, jstor.org/stable/25056466. Accessed 18 Apr. 2022.

Schweitzer, Ivy. “Anne Bradstreet Wrestles with the Renaissance.” Early American Literature, vol. 23, no. 3, 1988, pp. 291–312, JSTOR, jstor.org/stable/25056733. Accessed 18 Apr. 2022.

Citation:

Bradstreet, Anne. “The Author to Her Book.” Transatlantic Literature and Premodern Worlds, edited by Marissa Nicosia, et al., Pressbooks, 2025.

Lazovsky, Deven and Fernando Trejo. Introduction to Anne Bradstreet’s “The Author to Her Book.” Transatlantic Literature and Premodern Worlds, edited by Marissa Nicosia, et al., Pressbooks, 2025.

- Bradstreet begins the work with the implementation of an extended metaphor of being the mother to a defective child, her book, and calls its creator - her own mind - “feeble.” “Feeble” is defined by Oxford English Dictionary as “Lacking intellectual or moral strength.” This connects well to the blame Bradstreet puts on herself for the work being flawed. She expresses the guilt she feels over the quality of her work because it came from her mind alone, a mind she herself deems as lacking strength. Her mind is too weak to manifest something less flawed than what has presented to the world. This disregard of her own mind is tonally similar to the rest of the work in which Bradstreet condemns herself further for what she has done to the child in the metaphor and the work that it represents. This downplay of her writing could be interpreted in two different ways, one of which is an expression of genuine insecurity. Writing is often a way for people to express their innermost feelings, so maybe Bradstreet was just not confident in her writing. However, in some private writings, we do not see the same sort of downplaying that we do in her published pieces (Margerum). This leads to a second way to interpret Bradstreet’s negativity about her work: her use of humility could have been used to shield herself and her work from outside criticism. Additionally, by downplaying her work, she may have been seeking compliments and support from her readers. Bradstreet’s description of her book as her offspring references her role as a mother. Throughout much of the poem, Bradstreet treats the book as a child of her own, relating it to her own journey through motherhood. As a Puritan, motherhood was expected of her. She breaks from the expected by, while referring to the writing as a child of her own, insulting it by calling it “ill-form’d.” ↵

- Some close relations of Bradstreet’s were likely allowed to read her private writings. Though Bradstreet does not explicitly indicate that John Woodbridge, her in-law, was among them, one can infer she is referencing him since it was he who published her book. This line also brings forth the question of whether her book was published without her knowledge. While scholarly research can help us as readers attain more information on Bradstreet and her poem’s past, there is nothing that can indubitably prove whether or not she knew about her poems’ future. ↵

- The layered quality of this line means it could be utilized for either the extended metaphor that Bradstreet has crafted or could be used when discussing the reality that the work is representative of, and both notions harmonize with each other. This line lifts the veil of the mother/child metaphor and permits Bradstreet to express her true remorse over the publication of, or frustration with, the final product of her book. This line is important as it develops a concept relevant throughout this poem: Bradstreet is fearful of the exposure this offspring of hers will have to endure. ↵

- This line follows the same idea of the previous line, but in a much more hyperbolic sense. Bradstreet holds much remorse about exposing this blemished child to the light. “Light” could be employed in two different manners, either literally, which allows it to take on a hyperbolic quality, or metaphorically, and thus connects back to the previous notion of the “publick view” (Bradstreet, line 4) or a later line where Bradstreet drops the metaphor momentarily and refers to “Criticks” (Bradstreet, line 20). “Light” could be a metaphorical stand-in for the public eye, the critics who would be able to get their hands on her work and judge it. In both the literal and metaphorical senses, it shows the remorse that Bradstreet has regarding this child entering the world when she knows it is as flawed as it is. ↵

- Prior to discussing this line, there are two words that should be defined to give clearer context. “Visage” is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as, “An appearance or aspect. By the first visage, at first sight.” And “irksome” is defined by the same dictionary as, “Wearisome, tedious, tiresome; troublesome, burdensome, annoying. Formerly also, in wider sense, Distressing, painful; in early use, Disgusting, loathsome.” After reading these definitions, we can interpret this line as Bradstreet’s insulting of her work, calling its appearance annoying, burdensome, and disgusting. So, while Bradstreet uses a maternal tone and refers to the book as her child or offspring, she also insults it throughout the poem. She goes back and forth from expressing a motherly love to insulting her own “offspring.” These dramatic insults suggest that maybe she was using humility to her advantage rather than expressing her true thoughts on her work. ↵

- These lines support the idea that her book was published purposefully, rather than without her knowledge as she indicates elsewhere in the piece, since she indicates here that the publication of this book was necessary to improve her financial situation. However, historically speaking, we know that Anne Bradstreet was married to a politician, giving them opportunities and resources that other people would not have had. Even from childhood, Bradstreet had more monetary and social wealth than this poem accounts for. Putting this line into context with Bradstreet’s biographical details can lead to readers to question why she decided to describe herself as poor. All the regrets and remorse Bradstreet discussed come to a head in the final line. Bradstreet comes to terms with reality and acknowledges that the book-child is out in the world for better or for worse. It has been exposed to the light and there is no turning back on that reality. Although Bradstreet still condemns herself for the condition of what was birthed from her and the flaws that plague this offspring, she accepts this truth. This notion is supported in the article “Anxiety of Authorship in Anne Bradstreet's ‘The Author to Her Book’" in which Cirakli states “the defects and flaws that the writer discerns are part of her child and she can therefore never keep a complete distance. It seems that she loves the child, weakness and all.” The door referenced in this line is representative of letting the child be free in the world and to embrace the light. Bradstreet then relinquishes the regret she had and accepts the truth of it all, despite her dissatisfaction with the work. As this piece was included in the republishing of The Tenth Muse, it acts as an acknowledgement of both her regret and acceptance of the publication. Although frustrated with herself, she accepts the work as it is and lets it be free. ↵