48 “On Being Brought from Africa to America” (1773)

With an Introduction by Hajrah Khan

Phillis Wheatley

Introduction: Racism and Faith in Phillis Wheatley’s “On Being Brought From Africa To America”

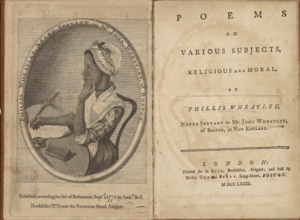

The border around Wheatley’s portrait reads “Phillis Wheatley, Negro Servant to Mr. John Wheatley, of Boston.”

Beneath her portrait is publishing information: “Published according to Act of Parliament, Sept. 1 1773 by Arch.d Bell. Bookseller no. 8 near the Saracens Head Aldgate.”

The text on the opposite page reads: “Poems on various subjects, religious and moral. By Phillis Wheatley, Negro Servant to Mr. John Wheatley of Boston in New England. London: Printed by A. Bell, Bookseller, Aldgate; and fold by Messrs. Cox and Berry, King-Street, Boston. M DCC LXXIII.”

Phillis Wheatley Peters was one of the first African-American poets and was born in West Africa, which is currently The Gambia or Senegal. Wheatley was captured, sold into slavery, and brought from Africa to Boston, Massachusetts at about seven years old (“Phillis Wheatley”). Here, John Wheatley purchased Phillis as a personal servant for his wife on July 11, 1761. John Wheatley named her after the ship that had transported her to America. Phillis Wheatley was educated by her enslavers, which was not common during this period. She was educated in English, Latin, and Greek, and wrote highly praised poetry. She published her first volume of poems, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, in 1773, and “On Being Brought from Africa to America” is contained in this volume. Wheatley experienced a lot of hardship as an enslaved person in the United States, which she reflects upon in her writing. Wheatley’s poems contained influences from her Christian faith, as well as from her African roots. Figure 2 shows Phillis Wheatley’s memorial statue in Boston where she lived and published her work.

Wheatley was a devout Christian and became close to her faith when she was enslaved as she faced many difficulties, one being the difficulty in finding a publisher as colonists were unwilling to support her work. Her enslaver, Mrs. Wheatley tried to help her find a publisher through advertisements in the Boston newspapers, but was ultimately unsuccessful. Later, the Wheatley’s son, Nathaniel, traveled with Phillis to London to search for a publisher. There in London she found Selina Hastings, the countess of Huntingdon, an abolitionist that helped Wheatley publish her first work. Wheatley married a freed black man named John Peters in 1778. She had three children with him, two of which she lost, and their surviving son remained sickly (“Phillis Wheatley”).

“On Being Brought From Africa To America” contains subjects of mercy, discrimination, and divinity. This poem is eight lines long and is written in iambic pentameter. Throughout this poem, Wheatley talks about God’s mercy and love for all people as well as the attitudes of Americans towards Africans. It creates a link between racism and biblical salvation to state how God created all people equally and loves all equally. The irony Wheatley uses in this poem is that many individuals consider themselves loyal Christians but refuse to accept this simple belief of equality through God. Wheatley criticizes the people that brought her from Africa and forced her to become a Christian, though she did grow close to it throughout her life and it helped her weather her hardships. Wheatley was strongly against the discrimination against African-Americans and wrote several letters to ministers and other leaders on freedom for the enslaved. Wheatley was a strong woman and proved many wrong as she showed them that Africans were just as intelligent and creative as those that wished to take advantage of them.

In this poem, Wheatley also used iambic pentameter to give her poem a natural flow, and every stanza has exactly ten syllables. Wheatley discusses her specific experience in the beginning and then switches to discussing the Black experience in America. There is a degree of forcefulness, almost as though her tone switches to anger, towards the end, as she chastises White Christians for their un-Christian attitude toward Black people.

“On Being Brought From Africa To America”

‘Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan[1] land,

Taught my benighted[2] soul to understand

That there’s a God, that there’s a Saviour too:

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

Some view our sable race with scornful eye,

“Their colour is a diabolic die[3].”

Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain[4],

May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train.

Sources:

“On Being Brought from Africa to America” edited by Dr. Robin DeRosa from The Open Education Anthology of Earlier American Literature licensed by CC BY

“Cain and Abel.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 13 Apr. 2022, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cain_and_Abel.

Citations:

Khan, Hajrah. “Racism and Faith in Phillis Wheatley’s ‘On Being Brought From Africa To America.'” Transatlantic Literature and Premodern Worlds, edited by Marissa Nicosia, et al., Pressbooks, 2025.

Wheatley, Phillis. “On Being Brought from Africa to America.” Transatlantic Literature and Premodern Worlds, edited by Marissa Nicosia, et al., Pressbooks, 2025.

- Wheatley begins this poem by describing the land from which she was brought as “pagan.” According to the Oxford English Dictionary the meaning of pagan is “A person of unorthodox, uncultivated or backward beliefs, tastes” or “a person who has not been converted to the current dominant views of a society, group, etc.; an uncivilized or unsocialized person, esp. a child.” This can be interpreted as Wheatley being brought from her native land as a non-Christian into a society that promoted Christianity. Wheatley converted to Christianity after coming from Africa, and she became close to her faith as it allowed her to have hope in herself in times of strife. According to Interesting Literature, “she states that it was ‘mercy’ or kindness that brought her from Africa to America.” Wheatley personifies “mercy” in her poem as though it was a person that guided her from her home of West Africa to America. ↵

- Wheatley experienced racism and hardship in America because she was brought from Africa and enslaved. In the second line, Wheatley describes her soul as “benighted” which the OED defines as “To involve in darkness, to darken, to the cloud. Also figurative, of the effect of sorrow, disappointment, etc., upon one's face, prospects, or life.” Benighted can also be used in a negative connotation to express the feeling of sorrow that she experienced as a Black individual in the Western world that praised Whiteness and considered it to be an indicator of the rich, enlightened, and blessed. Benighted in the context of this line (“Taught my benighted soul to understand”) can also represent how Wheatley did not know about Christianity before and was immersed in it after arriving in America. Benighted can interpreted in a racial sense in that Wheatley did experience racism and slavery because she was Black, but it can also be understood as the description of her soul before it was touched by Christianity. Her soul was benighted and full of sorrow until she learned that there was a savior, giving her hope despite her enslavement, as implied in the following line. The theme of racism and the Christian faith intertwine to convey what Wheatley went through and how she converted to Christianity and learned to trust in God’s plan. Wheatley redirects “benighted” as an overcoming of darkness that taught her soul to understand. ↵

- The OED defines “diabolic” as “Reminiscent or characteristic of a devil in nature or behavior; devilish, fiendish; evil, wicked.” Wheatley makes use of the phrase “diabolic die” to describe the way society viewed Black people as more or less as sinful or wicked because of their skin color. With the use of the phrase “diabolic die,” Wheatley was able to imply the sense of inherent evil that White people placed upon Black people through its “devilish” connotation. The word dye is spelled as “die,” which is an uncommon way to spell it in this context, as the OED defines it as “Die- Only in to make a die (of it) = to die or Dye- Colour or hue produced by, or as by, dyeing; tinge, hue.” ↵

- By the end of the poem, Wheatley makes a final religious acknowledgment by mentioning the racist way in which White society believed that African-Americans’ skin tone was reminiscent of the biblical figure of Cain. Cain’s role in the Hebrew and Christian Bibles entail a murder involving the two sons of Adam and Eve, wherein their older son Cain killed his younger brother Abel out of jealousy over God’s favor for him and for his sacrifices. Abel reminded Cain not to act in envy, but Cain killed his brother and was condemned by God to a life of wandering. According to LitCharts’s Samantha Zevanove, God then placed a mark on Cain that would serve as a warning to other people who might be motivated to harm Cain. Many Protestant Christians during this time believed that the mark of Cain was dark skin, hence the speaker's reference to being black as Cain. (Zevanove) Thus Wheatley reminded Christians that though African-Americans’ skin was theoretically as Black as Cain, Cain also had access to redemption and salvation through Christianity. Wheatley compares how Cain was the one that rejected God's message and was cursed and how Black people were considered as “evil as Cain” even when they were not. Wheatley makes the important point of how God treats everyone with mercy and equality no matter their race. ↵