2 Chapter 2: Mason Bee Biology

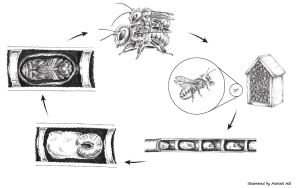

Unlike honey bees, mason bees are solitary. They don’t live in hives, have no queen, and don’t make honey. They complete just one generation per year and are active as adults for only 6–8 weeks in early to mid-spring.

During the cooler months, they remain in diapause as adults inside cocoons. When temperatures rise in spring, they chew their way out using their mandibles—males emerge a few days before females.

Males are short-lived and contribute little to pollination. They wait outside the nests and compete to mate with females as they emerge. Each female mates once, while males can mate multiple times.

After mating, females search for a nest site—often in hollow stems, reeds, or beetle burrows in wood. Mason bees also readily nest in artificial substrates, including cut Phragmites reeds, cardboard tubes with glassine liners, or grooved wooden blocks.

A female claims a nesting tunnel by marking it with a scent gland on her abdomen. After a few orientation flights, she begins foraging for pollen and nectar to provision her nest. Once she collects enough, she lays a single egg on top of the pollen mass. She then builds a mud partition using her strong mandibles, sealing off the cell before starting the next.

Once the tunnel is full, she caps the entrance with a thick mud plug to protect her offspring from predators and parasites. In ideal conditions, a female should be able to complete between 1 and 2 cells per day. She typically makes 5-12 cells per tunnel, and will fill 2-3 tunnels in her lifetime. This reproductive output can be limited by many factors, including predations, pesticide exposure, and extended periods of cold and rainy weather.

For mason bees, access to mud is just as important access to flowering plants. In the video below, Osmia lignaria and Osmia cornifrons are both collecting mud from the same place at the same time. Some mason bee consultants contend that orchards with very sandy or silty soil may benefit from provisioning clay-like soil in the vicinity of managed nest sites, although this benefit has not been experimentally validated.

Inside the nest, the egg hatches into a larva, consumes the pollen, and spins a silk cocoon for protection. The bee pupates and develops into an adult by early fall. It remains dormant in the cocoon through the winter, ready to emerge when spring returns and begin the cycle again.

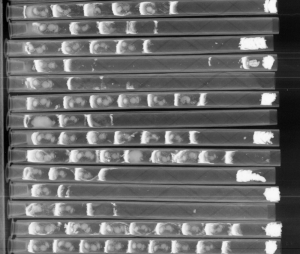

Researchers often use X-radiography as a nonlethal diagnostic tool for mason bee research. Pictured here, you can see mason bee larvae is different stages of development; this picture was taken in late summer, after most of the mason bees have pupated. Note that females are laid first (on the left), followed by male eggs. Male mason bees typically receive smaller pollen provisions and have a smaller body size. See if you can distinguish the males from females from this picture!

Researchers often use X-radiography as a nonlethal diagnostic tool for mason bee research. Pictured here, you can see mason bee larvae is different stages of development; this picture was taken in late summer, after most of the mason bees have pupated. Note that females are laid first (on the left), followed by male eggs. Male mason bees typically receive smaller pollen provisions and have a smaller body size. See if you can distinguish the males from females from this picture!

A Quick Lesson on the Birds and the (Mason) Bees

Did you know that a female mason bee can control the sex of each individual egg that she lays as she builds her nest? Mason bees pre-determine the sex of their offspring via a special reproductive strategy that scientists call ‘haplodiploidy’. One of the first things that a female mason bee does after she sheds her cocoon is mate with a male. When the bees mate, the sperm from the male travels through the reproductive tract of the female and is stored in a specialized storage organ called a ‘spermatheca’. After mating, the female will find a nest where she will collect and store an individual pollen and nectar mass for each one of her offspring.

Mother bees typically lay females at the back end of their nest, followed by males towards the front end of the nest. She has precise control over the sex of her offspring due to haplodiploidy. For mason bees (and all other bees and wasps) mothers determine the sex of their offspring by deciding whether to use sperm stored in the spermatheca to fertilize the egg or not. If the egg is fertilized, the egg is destined to become a diploid female. The egg and sperm combine to yield two sets of paired chromosomes in the offspring, just like all of us humans have. If the egg does not get fertilized by sperm stored in the spermatheca, the egg is destined to become a haploid male. Without any sperm fertilizing the egg, there is no second set of chromosomes for the developing bee to inherit. This means that all male bees and wasps contain half the amount of genetic information that female bees and wasps do!

So, as a mother mason bee establishes her nest, the first eggs that she lays are fertilized using the sperm stored in her spermatheca so that they will develop into females. After she constructs a few female cells, she will transition to producing male offspring – and these are the eggs that will be left unfertilized, so that they will develop into males.