Introduction

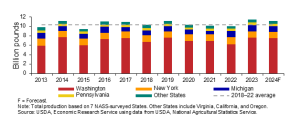

Tree fruit production represents a significant portion of the specialty crops sector in the Northeastern United States. In 2021, Pennsylvania alone boasted over 23,000 acres of tree fruit orchards in production (Weber 2021) and consistently ranks among the top four apple-producing states nationwide (USDA ERS 2024).

Efficient pollination is essential for successful orchard management. For decades, fruit producers have relied primarily on managed honey bee colonies due to their transportability, well-studied biology, and long history of use. However, honey bee pollination presents limitations—colonies do not always meet the pollination demands of tree fruit crops. Commercial honey bees face numerous stressors, including parasites, pathogens, nutritional deficits, and pesticide exposure (Steinhauer et al. 2018). As a result, recent studies suggest that the beekeeping industry may struggle to keep pace with rising demand for pollination services (Aizen et al. 2019). Beekeepers have reported persistent high overwintering losses (~40%) over the past decade, leading to a springtime shortage of viable hives (Steinhauer et al. 2021).

The horn-faced mason bee (Osmia cornifrons) is a promising alternative managed pollinator that could help bridge this supply-demand gap. A proven pollinator of spring-blooming rosaceous crops such as apple, tart cherry, and almond, O. cornifrons has been shown to improve fruit set and yield when used alone or in combination with honey bees (Pitts-Singer et al. 2018). Their four-to-six-week active foraging period can be timed to coincide with bloom through standardized incubation and management practices, allowing growers flexibility in deployment (Bosch & Kemp 2001). Mason bees typically forage within 60 meters of their nests (Rust 1974) and are active in cooler and wetter conditions than honey bees (Vincens & Bosch 2000). Management practices for mason bees have been established and continue to evolve since their introduction to agriculture nearly 80 years ago (Biddinger 2018).

Despite their potential, broader adoption of O. cornifrons for pollination in Northeastern orchards is hindered by a lack of training, knowledge, and accessible management resources. Introduced from Japan to the Mid-Atlantic in the 1990s, the species has since naturalized across much of the U.S. (Biddinger 2018). Yet, intentional management for orchard pollination has not been widely maintained, and technical expertise in mason bee husbandry is rare. Proficiency in managing O. cornifrons requires at least a full year of hands-on experience, and only a limited number of practitioners have received such training. While many studies have addressed the biology and health of horn-faced bees (McKinney & Park 2012; Vaudo et al. 2020), fewer have examined the applied aspects of their management—such as optimal stocking rates, nesting materials, or the impact of supplemental forage.

Current recommendations for orchard bee management traditionally focus on Osmia lignaria (blue orchard bee) in western orchards. However, the climate, scale, and intensity of orchard management in the western U.S. differ significantly from that of Pennsylvania, limiting the direct applicability of those practices to O. cornifrons in the Northeast.

In recent years, researchers have contributed evidence-based guidance to improve mason bee management, addressing field practices (Boyle & Pitts-Singer 2017), parasite control (White et al. 2009), nesting sanitation (MacIvor & Packer 2015), and overwintering care (Schenk et al. 2018). However, these findings have not yet been compiled into a single technical resource tailored to growers and consultants.

This e-book is intended to serve as a living reference for orchardists and backyard gardeners interested in managing mason bees for pollination of spring-blooming crops, particularly tree fruit species grown in Pennsylvania such as apple, pear, and cherry. Here, I synthesize all recommended practices for setting up, caring for and maintaining your own horn-faced bee populations, linking to external complementary resources where applicable.

Special focus is given to the two most commonly managed mason bee species in the United States—Osmia cornifrons (horn-faced bee) and Osmia lignaria (blue orchard bee). While many best practices shared here are adapted from research on O. lignaria propinqua, a native species primarily used in western almond orchards, this handbook emphasizes management practices tailored to the Mid-Atlantic region, particularly Pennsylvania and New York.