9.1 Intelligence

Learning Objectives

- Define intelligence.

- Compare the different theoretical approaches to intelligence.

- Outline the biological and environmental determinants of intelligence.

- Apply the knowledge of environmental influences on intelligence to enhancing learning.

Defining intelligence

Psychologists have defined intelligence in many ways. In this book, we will consider the concept of intelligence to reflect an individual’s ability to think and learn from experience, to solve problems and adapt to new situations. While psychologists have a hard time agreeing on a specific definition of ability, it is agreed upon that intelligence is highly predictive of how successful one will be in terms of school. It predicts how well will do in occupations in general. It also can predict health and longevity (Gottfredson & Dreary, 2004).

In the early 1900s, the French psychologist Alfred Binet (1857–1914) and his colleague Henri Simon (1872–1961) began working in Paris to develop a measure that would differentiate students who were expected to be better learners from students who were expected to be slower learners. The goal was to help teachers better educate these two groups of students. Binet and Simon developed what most psychologists today regard as the first intelligence test, which consisted of a wide variety of questions that included the ability to name objects, define words, draw pictures, complete sentences, compare items, and construct sentences.

The psychologist Charles Spearman (1863–1945) hypothesized that there must be a single underlying construct that all of these items measure. He called the construct that the different abilities and skills measured on intelligence tests have in common – the general intelligence factor (g). Virtually all psychologists now believe that there is a generalized intelligence factor, g, that relates to abstract thinking and that includes the abilities to acquire knowledge, to reason abstractly, to adapt to novel situations, and to benefit from instruction and experience (Gottfredson, 1997; Sternberg, 2003). People with higher general intelligence learn faster.

Soon after Binet and Simon introduced their test, the American psychologist Lewis Terman (1877–1956) developed an American version of Binet’s test that became known as the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Test. The Stanford-Binet is a measure of general intelligence made up of a wide variety of tasks including vocabulary, memory for pictures, naming of familiar objects, repeating sentences, and following commands.

Although there is general agreement among psychologists that g exists, there is also evidence for specific intelligence (s), a measure of specific skills in narrow domains. One empirical result in support of the idea of s comes from intelligence tests themselves. Although the different types of questions do correlate with each other, some items correlate more highly with each other than do other items; they form clusters or clumps of intelligences.

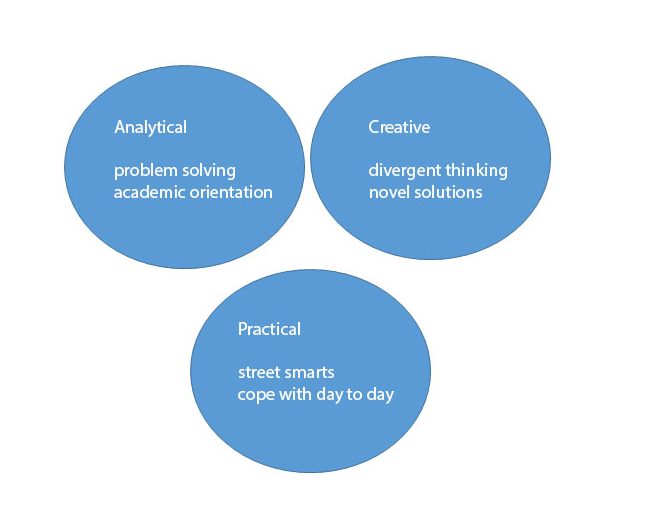

One advocate of the idea of multiple intelligences is the psychologist Robert Sternberg. Sternberg has proposed a triarchic (three-part) theory of intelligence that proposes that people may display more or less analytical intelligence, creative intelligence, and practical intelligence. Analytic intelligence is similar to the traditional view of intelligence, solving problems where a single answer is correct. Practical intelligence represents a type of “street smarts” or “common sense” that is learned from life experiences. Creative intelligence reflects coming up with unique or different solutions. This can be indicated with associated with divergent thinking, the ability to generate many different ideas for or solutions to a single problem (Tarasova, Volf, & Razoumnikova, 2010), e.g., How many uses for a paper clip can you think of?.

Long Description

Description of the image

Title: Sternberg’s Components of the Triarchic Intelligence Theory

3 Circles: On the top left:

- Analytical – problem solving, academic orientation

On the top right:

- Creative – divergent thinking, novel solutions

On the bottom:

- Practical – street smarts, cope with day to day

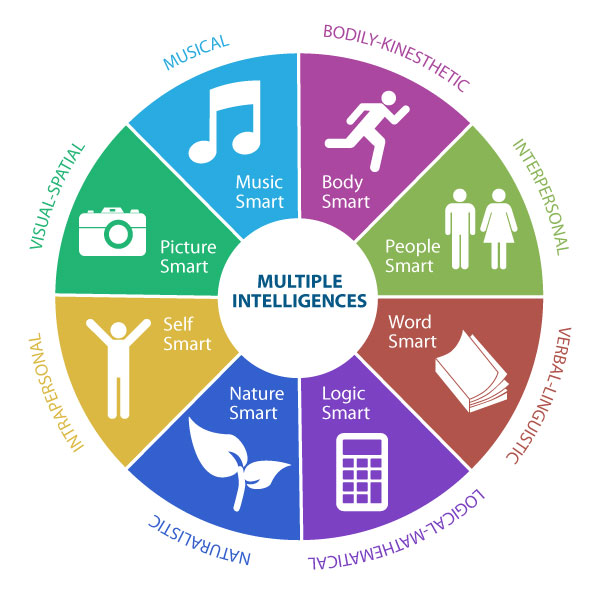

Another champion of the idea of multiple intelligences is the psychologist Howard Gardner (1983, 1999). Gardner argued that it would be evolutionarily functional for different people to have different talents and skills, and proposed that there are eight intelligences that can be differentiated from each other. These are summarized in Figure 9.2. Gardner noted that some evidence for multiple intelligences comes from the abilities of autistic savants, people who score low on intelligence tests overall but who nevertheless may have exceptional skills in a given domain, such as math, music, art, or in being able to recite statistics in a given sport (Treffert & Wallace, 2004).

Long Description

Description of the image

Title: Gardner’s Multiple Intelligence

Big ring with 8 sections. Each section is a different color.

- Light Blue: Musical; Music Smart

- Magenta: Body-Kinesthetic; Body Smart

- Olive Green: Interpersonal; People Smart

- Red: Verbal-Linguistic; Word Smart

- Purple: Logical-Mathematical; Logic Smart

- Blue: Naturalistic; Nature Smart

- Yellow: Intrapersonal; Self Smart

- Green: Visual-Spatial; Picture Smart

The idea of multiple intelligences has been influential in the field of education, and teachers have used these ideas to try to teach differently to different students. For instance, to teach math problems to students who have particularly good kinesthetic intelligence, a teacher might encourage the students to move their bodies or hands according to the numbers. On the other hand, some have argued that these “intelligences” sometimes seem more like “abilities” or “talents” rather than real intelligence. And there is no clear conclusion about how many intelligences there are. Are sense of humor, artistic skills, dramatic skills, and so forth also separate intelligences? Furthermore, and again demonstrating the underlying power of a single intelligence, the many different intelligences are in fact correlated and thus represent, in part, g (Brody, 2003).

Influences on Intelligence

The Brain and Intelligence

The brain processes underlying intelligence are not completely understood, but current research has focused on four potential factors: brain size, sensory ability, speed and efficiency of neural transmission, and working memory capacity.

There is mixed evidence that smarter people have bigger brains. McDaniel’s (2005) review showed that studies measuring brain volume using neuroimaging techniques find that larger brain size is correlated with intelligence. However, other studies found this correlation only accounted for a small part of intelligence (Andreasen et al., 1993, Witelson et al., 2006). There are many factors that contribute to intelligence. It is important to remember that these correlational findings do not mean that having more brain volume causes higher intelligence. It is possible that growing up in a stimulating environment that rewards thinking and learning may lead to greater brain growth (Garlick, 2003), and it is also possible that a third variable, such as better nutrition, causes both brain volume and intelligence.

Another possibility is that the brains of more intelligent people operate faster or more efficiently than the brains of the less intelligent. Some evidence supporting this idea comes from data showing that people who are more intelligent frequently show less brain activity (suggesting that they need to use less capacity) than those with lower intelligence when they work on a task (Haier, Siegel, Tang, & Abel, 1992). And the brains of more intelligent people also seem to run faster than the brains of the less intelligent. Research has found that the speed with which people can perform simple tasks—such as determining which of two lines is longer or pressing, as quickly as possible, one of eight buttons that is lighted—is predictive of intelligence (Deary, Der, & Ford, 2001). Intelligence scores also correlate at about r = .5 with measures of working memory (Ackerman, Beier, & Boyle, 2005), and working memory is now used as a measure of intelligence on many tests.

Intelligence and Genetics

Intelligence has both genetic and environmental causes, and these have been systematically studied through a large number of twin and adoption studies (Neisser et al., 1996; Plomin, 2003). These studies have found that between 40% and 80% of the variability in IQ is due to genetics, meaning that overall genetics plays a bigger role than does environment in creating IQ differences among individuals (Plomin & Spinath, 2004). The IQs of identical twins correlate very highly (r = .86), much higher than do the scores of fraternal twins who are less genetically similar (r = .60). And the correlations between the IQs of parents and their biological children (r = .42) is significantly greater than the correlation between parents and adopted children (r = .19). The role of genetics gets stronger as children get older. The intelligence of very young children (less than 3 years old) does not predict adult intelligence, but by age 7 it does, and IQ scores remain very stable in adulthood (Deary, Whiteman, Starr, Whalley, & Fox, 2004).

Intelligence and Experience

But there is also evidence for the role of nurture, indicating that individuals are not born with fixed, unchangeable levels of intelligence. Twins raised together in the same home have more similar IQs than do twins who are raised in different homes, and fraternal twins have more similar IQs than do non-twin siblings, which is likely due to the fact that they are treated more similarly than are siblings.

The fact that intelligence becomes more stable as we get older provides evidence that early environmental experiences matter more than later ones. Environmental factors also explain a greater proportion of the variance in intelligence for children from lower-class households than they do for children from upper-class households (Turkheimer, Haley, Waldron, D’Onofrio, & Gottesman, 2003). This is because most upper-class households tend to provide a safe, nutritious, and supporting environment for children, whereas these factors are more variable in lower-class households.

Social and economic deprivation can adversely affect IQ. Children from households in poverty have lower IQs than do children from households with more resources even when other factors such as education, race, and parenting are controlled (Brooks-Gunn & Duncan, 1997). Poverty may lead to diets that are undernourishing or lacking in appropriate vitamins, and poor children may also be more likely to be exposed to toxins such as lead in drinking water, dust, or paint chips (Bellinger & Needleman, 2003). Both of these factors can slow brain development and reduce intelligence.

If impoverished environments can harm intelligence, we might wonder whether enriched environments can improve it. Government-funded after-school programs such as Head Start are designed to help children learn. Research has found that attending such programs may increase intelligence for a short time, but these increases rarely last after the programs end (McLoyd, 1998; Perkins & Grotzer, 1997). But other studies suggest that Head Start and similar programs may improve emotional intelligence and reduce the likelihood that children will drop out of school or be held back a grade (Reynolds, Temple, Robertson, & Mann 2001).

Intelligence is improved by education; the number of years a person has spent in school correlates at about r = .6 with IQ (Ceci, 1991). In part this correlation may be due to the fact that people with higher IQ scores enjoy taking classes more than people with low IQ scores, and they thus are more likely to stay in school. But education also has a causal effect on IQ. Comparisons between children who are almost exactly the same age but who just do or just do not make a deadline for entering school in a given school year show that those who enter school a year earlier have higher IQ than those who have to wait until the next year to begin school (Baltes & Reinert, 1969; Ceci & Williams, 1997). Children’s IQs tend to drop significantly during summer vacations (Huttenlocher, Levine, & Vevea, 1998), a finding that suggests that a longer school year, as is used in Europe and East Asia, is beneficial.

It is important to remember that the relative roles of nature and nurture can never be completely separated. A child who has higher than average intelligence will be treated differently than a child who has lower than average intelligence, and these differences in behaviors will likely amplify initial differences. This means that modest genetic differences can be multiplied into big differences over time.

Key Takeaways

- Intelligence is the ability to think, to learn from experience, to solve problems, and to adapt to new situations. Intelligence is important because it has an impact on many human behaviors.

- Psychologists believe that there is a construct that accounts for the overall differences in intelligence among people, known as general intelligence (g).

- There is also evidence for specific intelligences (s), measures of specific skills in narrow domains, including creativity and practical intelligence.

- Brain volume, speed of neural transmission, and working memory capacity are related to IQ.

- Between 40% and 80% of the variability in IQ is due to genetics, meaning that overall genetics plays a bigger role than does environment in creating IQ differences among individuals.

- Intelligence is improved by education and may be hindered by environmental factors such as poverty.

Exercises

Discuss:

Reflect on your childhood. What family and/or educational experiences seem to have had an impact on your intellectual development? Would you say your background was overall deprived or enriched? In what ways?