Using Psychology to Talk about Multicultural Themes

Talking about diversity and multiculturalism often brings up a variety of strong feelings for people. When strong feelings – of any kind – are present, it can become harder to effectively and meaningfully learn. In this chapter, we’ll use psychological theories to explore how people can react to difficult or nuanced conversations, how to effectively dialogue, and how to manage personal reactions while doing so. This chapter will review how people learn meaningfully, how to modulate emotional responses when learning new concepts that challenge existing beliefs, and how to engage in dialogue to share learning and understanding with others.

Learning and Schemas

First, we need to discuss the process of learning within the context of multicultural education. Everyone enters a new environment, such as a classroom, with existing beliefs, attitudes, and knowledge about a particular topic called a schema. Schemas develop out of daily experiences, not just classroom experiences. For example, my 16-month-old son went to a petting zoo and fed some goats. Unlike some of the older children, he was perfectly comfortable offering the goats food and did not show any fear or caution near the animals. My son is growing up with a large-breed dog at home, and therefore his schema for how to engage with large animals involved feeling safe, being respectful of the animals’ space, and offering them food. In contrast, other young children who had not encountered large animals before had little positive information to work with, and so exercised more caution around the goats.

Using the language of schemas, learning happens when we take new information and either (1) place it into an existing schema or (2) create a new schema. If you have taken a Developmental Psychology class, you may remember learning about how children place new experiences into their schemas. A young child may have a schema for “dog,” where “dog” refers to any four-legged animal that has a tail. Upon meeting a corgi for the

Corgis’ tails are often removed for aesthetic purposes.

first time, the child may have to adapt their “dog” schema to include four-legged animals that bark and only sometimes have tails. The first time a teen enters a romantic relationship, they must create a new schema (“how to be a romantic partner”) based on their experiences.

When it comes to learning about multiculturalism, most people will rely on many schemas to approach new information. Some schemas explain our identities – so I have a schema for what it is to be a woman, built on my lived experience, readings and research I teach, and experiences and stories I hear from women around me or in the media.

Schemas can hold correct, incorrect, and under-developed ideas or information, and many people hold incorrect information without ever really thinking about it (how many people have incorrect understandings of STI prevention or how the U.S. government works?). Have you ever learned something incorrectly, and then tried to go back and correct your information? It can be difficult to re-build a schema. And yet, much of multicultural psychology requires work around challenging previously held beliefs. This requires a third type of learning: changing an existing schema. For example, a girl who grows up seeing only male doctors and scientists may unconsciously create a schema for doctor that includes being male. If her school counselor encourages her to apply for a science scholarship, she may have a difficult time moving forward, because entering a STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) field goes against her schema. (in Chapter 5 we will review the concept of “Stereotype Threat” which is similar). To change her schema, this girl would need exposure to female doctors – role models or examples – and assistance in seeing how she herself can become a doctor, that is, she would need to see some ways to implement or apply the idea that girls can be doctors.

In order to explore new ideas, research, and examples, we need to be able to identify the information we bring into the classroom with us. This helps us understand our biases, which are innate processes that all humans have. The practice of understanding bias is a key part of the research process in multicultural psychology, which we will discuss in Chapters 3-4.

As noted at the beginning, it is difficult to learn – especially to change an existing schema – when emotions are strong. Think of a time you have been quite nervous, or angry, or scared. Were you capable of sitting down to read a textbook or scholarly article at that time? Would you have been able to outline an essay?

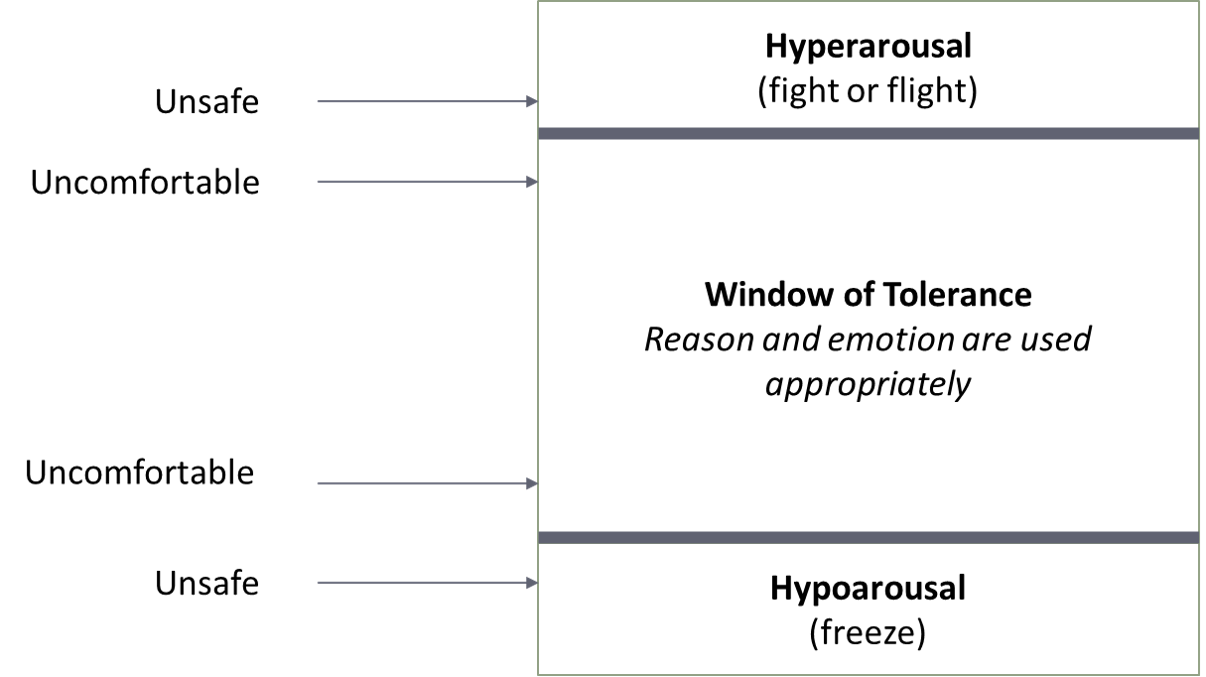

Learning, Emotions, and the Window of Tolerance

The Window of Tolerance is a concept from trauma psychology (Ogden et al., 2006; Siegel, 1999) that explains how emotions and related physiological arousal impact our ability to reason. When we are in our “window” we can use both reason and emotion. We can hold difficult conversations with colleagues, peers, and family. We can problem solve and learn.

Some events can cause you to go into hyperarousal – your heart rate and blood pressure increase, your thoughts race, and your breathing speeds up. People describe this state as anxiety, panic, or anger; evolutionary and trauma psychologists would describe it as “fight or flight.” Other people may go into hypoarousal after exposure to the same event. In this state, your heart rate and blood pressure slow, your thoughts slow, and you feel lethargic and unmotivated. People describe this state as being unmotivated, stuck, or shut down. Evolutionary and trauma psychologists describe this as “freeze.” While not talked about as much as “fight or flight,” “freeze” is just as common and essentially mimics the animal defense of “playing dead” as a means of survival.

In both hyperarousal and hypoarousal states, the goal is not to learn new information, it is to protect yourself. Fight, flight, or freeze ideally happens when we encounter a danger. In past eras, this could be a wild animal or an enemy group. Unfortunately, fight, flight, or freeze happens with perceived danger as well. Depending on this person, this can include being criticized or challenged by a peer or professor in class, being given feedback about using a multicultural term incorrectly, or being asked to defend a particular opinion. In many cases, this perceived danger certainly involves being uncomfortable, but it does not involve actual danger.

One of the first goals of learning how to have challenging conversations and self-reflection is to learn the difference between danger and being uncomfortable. The goal is to stay in your window of tolerance when you are uncomfortable (perhaps near the edges). While all humans generally prefer comfort to discomfort, most of our development happens when we are uncomfortable – but safe. Have you heard the term growing pains, or experienced them? Similarly, if you have been to physical therapy, psychotherapy, or the gym, you know that growth and improvement involves being uncomfortable.

There are several ways to make your window bigger. Eating well, drinking water, and getting enough sleep are all documented ways of keeping your emotions balanced. Feeling sick or having additional stressors (say, an exam, or a pandemic) make your window smaller. On any given day, your window size may fluctuate.

How do you use the phrase “trigger,” if at all? When you say you have been triggered, what sorts of emotional responses do you mean? Where in the Window of Tolerance chart would you place yourself (in Hyperarousal? Near the middle of the Window itself, or toward an edge?)? What do you need to do in order to calm yourself?

Finally, it is worth noting that people often avoid, or try to avoid, their triggers. In fact, that is often the goal of a trigger warning. Sometimes this is necessary to maintain psychological safety. Other times, avoiding a particular event or topic only reinforces discomfort. That is, if you continue to avoid something, your belief that this thing is too difficult to deal with will grow. This is why procrastination is so hard to overcome. It is also why most therapies for trauma involve exposure interventions, where a person must (safely) confront their trigger, and then learn to make new, safe connections to the trigger (Weisman & Rodebaugh, 2018).

Learning Through Dialogue

Learning new information can come from reading a textbook, a scholarly article, listening to a classmate or friend, or watching Netflix. Learning through group dialogue is effective at your family’s dinner table, in a classroom, and in group therapy. As you have likely been in at least one of these settings, you know that there are effective ways to talk in groups and ineffective ways.

Intergroup Dialogue (IGD) has become a powerful tool in classroom and public settings. In IGD, participants from different socio-cultural backgrounds sit down to understand one another’s experiences. When discussing cultural experiences, the goal is to develop an understanding of inequality (Program on Intergroup Relations, 2020). IGD is not a discussion, because “discussion” in classroom settings often refers to a purely cognitive or academic exploration of a concept and aims to maintain neutrality. Multiculturalism recognizes that neutrality and objectivity cannot exist because people have different experiences that they bring to a conversation. IGD is also not a debate, where the goal is to win a particular argument.

IGD aligns with multicultural psychology seamlessly. First, many scholars of multicultural training in psychology emphasize the need for cultural contact in order to develop a multicultural awareness (e.g., Hook et al., 2016). Cultural contact requires engaging with people from different cultural backgrounds and can be achieved through IGD. Second, IGD and psychological practice (e.g., practicing counseling or psychotherapy) require a similar skill set, particularly when it comes to listening. The University of Michigan’s Program on Intergroup Relations summarizes four types of listening:

- Internal Listening: Most people practice internal listening – the listener is more attuned to their personal reactions and thoughts when another person is speaking. Here, a listener might look for a flaw in what the speaker is saying, focus on formulating their response rather than attending fully to the speaker, or search for ways in which their own experiences overlap with the speaker’s. This happens for a variety of reasons, and not all of the reasons are necessarily “bad,” but in the context of IGD, where the goal is to find common understanding, it can slow down progress.

- Generous Listening: This requires a curiosity about the speaker’s experience and message. Here, the listener is more focused on the speaker than themselves. Generally, a generous listener will ask open-ended questions of the speaker in order to elicit more information or understanding.

-

- Generative Listening: Here, a listener is able to identify themes or patterns that develop as multiple speakers share and can suggest these ideas to the group. This process is generative – that is, it creates new knowledge or ideas from what has been said.

- Global Listening: “Global” refers to the idea that IGD is not just what is spoken in the room, it is also how something is spoken and how it is heard. Listeners will notice not just the speaker’s words, tone, and body language, but will also notice how others in the room respond to the speaker – are they shifting in their seats, making eye contact, or changing a facial expression?

Conclusion

In order to meaningfully learn about cross-cultural and multicultural psychology, we must identify and reflect on our existing schemas and be willing to replace these schemas with new information when necessary. Because of the personal and emotional dimensions of cultural learning, this often requires us to be aware of anxiety-provoking topics and to develop the skills to moderate these reactions. The Window of Tolerance is a helpful way to conceptualize our coping skills and decide whether we are unsafe or uncomfortable. Changing schemas and moderating emotional responses will occur through cultural contact in intergroup dialogues, which will help all of us build a common, deeper understanding of cultural experiences. These skills are critical to any job or relationship, and those with an interest in psychology as a career will find that these skills are foundational to future work.

References

Bruning, R., Schraw, G., Norby, M., & Ronning, R. (2004). Cognitive psychology and instruction (4th ed.). Pearson Education.

Hook, J. N., Watkins, Jr., C. E., Davis, D. E., Owen, J., Van Tongeren, D. R., & Ramos, M. J. (2016). Cultural humility in psychotherapy supervision. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 70(2), 149-166. https://www.ingentaconnect.com/contentone/afap/ajp/2016/00000070/00000002/art00001

Jones, M. G., & Brader-Araje, L. (2002). The impact of constructivism on education: Language, discourse, and leaning. American Communication Journal, 5 , 1–10. American Communication Journal

Ogden, P., Minton, K., & Pain, C. (2006). Trauma and the body: A sensorimotor approach to psychotherapy. Norton.

Siegel, D. J. (1999). The developing mind: How relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are. Guilford Press.

University of Michigan. (2020). The Program on Intergroup Relations. The Program on Intergroup Relations

Weisman, J. S., & Rodebaugh, T. L. (2018). Exposure therapy augmentation: A review and extension of techniques informed by an inhibitory learning approach. Clinical Psychology Review, 59, 41-51. ScienceDirect, Exposure therapy augmentation: A review and extension of techniques informed by an inhibitory learning approach

Media Attributions

Photo by Alvan Nee on Unsplash

Photo by AllGo – An App For Plus Size People on Unsplash

Long Description

The diagram shows a box with three rows. The top row is labeled “Hyperarousal (fight or flight)” and is labeled as unsafe. The middle row is the largest and is labeled “Window of Tolerance (reason and emotion are used appropriately).” The top and bottom spaces of this middle row are labeled as uncomfortable. The bottom row is labeled “Hypoarousal (freeze)” and is labeled as unsafe. Return

Media Attributions

- alvan-nee-Qz3l8A2Vs9w-unsplash © Alvin Nee

- Window of Tolerance picture

- allgo-an-app-for-plus-size-people-1GEsAeUv5dU-unsplash