Historical & Current Research Perspectives

Much of the current psychological research continues to rely on homogeneous groups that fail to represent, or generalize, to all persons. This becomes a significant issue when researchers and clinicians are attempting to understand how children learn in school, how college students handle depressive symptoms, and how families adjust to transitions (e.g., moving homes, financial stressors, or divorce/separation) and use only one group of people to draw conclusions about all persons.

Often, these homogeneous samples are referred to as WEIRD participants: Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic. As of 2010, WEIRD participants comprise over three-quarters of psychological study’s samples. The authors of this analysis, Drs. Henrich, Heine, and Norenzayan (2010), point out that many of these WEIRD participants in U.S. psychological studies are college students. A great group (including you, reader), but not representative of humanity as a whole.

Cross-cultural and multicultural psychology scholars focus on developing research questions, recruiting samples, and disseminating information that represent diverse populations. However, there are barriers to each step of the research process due to historical and contemporary incidents, both within social science and health research and a global context. Scholars need to be aware of these issues before engaging in cross-cultural and/or multicultural research activity.

Historical Perspectives

Psychological Frameworks to Justify Prejudice & Racism

Psychology, as a science, is a western family of theories to explain human behavior. That is, psychological theories emerged from western (European, and later, American) physicians, psychiatrists, and experimenters who did not take into account non-western views. Thus, many current theories within psychology may not hold in non-western cultures. Moreover, this development led to “othering” groups that did not fit the theories proposed by early psychologists. “Othered” groups were typically persons who were seen as “abnormal” or behaved inconsistently with the dominant social group. This included immigrants, enslaved and formerly enslaved persons in the U.S., and persons with intellectual disabilities. Social science was often used as a tool to defend or justify prejudicial public policy, including slavery, segregation, and other civil rights infringements. While this seems, at face value, to apply more to historical perspectives rather than contemporary perspectives, there are recent examples of using social science to justify prejudice. For example, Herrnstein and Murray’s (1994) “The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life” used faulty assumptions about IQ and intelligence to promote U.S. policies many have condemned as racist and classist (we will discuss this further in chapter 6).

As the majority of social scientists now challenge many of these early perspectives, some of these perspectives remain unchallenged by the majority. Sigmund Freud, often credited as one of the fathers of psychology, framed religious beliefs as pathological and superstitious. Later generations of psychologists propelled these beliefs forward, such as Albert Ellis, who created rational-emotive behavior therapy in the 1950’s (Ellis, 1993; a form of cognitive behavior therapy). Ellis often categorized religious beliefs as a form of “irrational thought,” which he defined as a central component of psychopathology. Today, many psychologists continue to mis-interpret religious beliefs and are more likely to over-diagnoize, or pathologize, someone who holds religious beliefs compared to persons who do not express religious beliefs (Vieten et al., 2013). Not surprisingly, religious communities may therefore be reluctant to participate in psychological studies.

Exploitation of Groups for Scientific Study

The history of health and social science-related research includes devastating examples of human exploitation and harm. Often, this exploitation and harm occurred in communities that were marginalized in any given locale and time period. This includes research done without participant consent on persons with intellectual disabilities, including the study of sterilization procedures during the U.S. eugenics movement, the Tuskegee syphilis trials (where African American men were injected with syphilis and then intentionally not treated), and medical and psychological experiments conducted on concentration camp prisoners during the Holocaust. The creation of Institutional Review Boards, which review and approve of all research studies before they can begin, and emergence of ethics codes for various scientific professions have kept many exploitative practices from continuing (see the APA’s Ethical Principles, listed below).

Principle A: Beneficence and Nonmaleficence Psychologists strive to benefit those with whom they work and take care to do no harm. In their professional actions, psychologists seek to safeguard the welfare and rights of those with whom they interact professionally and other affected persons, and the welfare of animal subjects of research. When conflicts occur among psychologists’ obligations or concerns, they attempt to resolve these conflicts in a responsible fashion that avoids or minimizes harm. Because psychologists’ scientific and professional judgments and actions may affect the lives of others, they are alert to and guard against personal, financial, social, organizational, or political factors that might lead to misuse of their influence. Psychologists strive to be aware of the possible effect of their own physical and mental health on their ability to help those with whom they work.

Principle B: Fidelity and Responsibility Psychologists establish relationships of trust with those with whom they work. They are aware of their professional and scientific responsibilities to society and to the specific communities in which they work. Psychologists uphold professional standards of conduct, clarify their professional roles and obligations, accept appropriate responsibility for their behavior, and seek to manage conflicts of interest that could lead to exploitation or harm. Psychologists consult with, refer to, or cooperate with other professionals and institutions to the extent needed to serve the best interests of those with whom they work. They are concerned about the ethical compliance of their colleagues’ scientific and professional conduct. Psychologists strive to contribute a portion of their professional time for little or no compensation or personal advantage.

Principle C: Integrity Psychologists seek to promote accuracy, honesty, and truthfulness in the science, teaching, and practice of psychology. In these activities psychologists do not steal, cheat or engage in fraud, subterfuge, or intentional misrepresentation of fact. Psychologists strive to keep their promises and to avoid unwise or unclear commitments. In situations in which deception may be ethically justifiable to maximize benefits and minimize harm, psychologists have a serious obligation to consider the need for, the possible consequences of, and their responsibility to correct any resulting mistrust or other harmful effects that arise from the use of such techniques.

Principle D: Justice Psychologists recognize that fairness and justice entitle all persons to access to and benefit from the contributions of psychology and to equal quality in the processes, procedures, and services being conducted by psychologists. Psychologists exercise reasonable judgment and take precautions to ensure that their potential biases, the boundaries of their competence, and the limitations of their expertise do not lead to or condone unjust practices.

Principle E: Respect for People’s Rights and Dignity Psychologists respect the dignity and worth of all people, and the rights of individuals to privacy, confidentiality, and self-determination. Psychologists are aware that special safeguards may be necessary to protect the rights and welfare of persons or communities whose vulnerabilities impair autonomous decision making. Psychologists are aware of and respect cultural, individual, and role differences, including those based on age, gender, gender identity, race, ethnicity, culture, national origin, religion, sexual orientation, disability, language, and socioeconomic status, and consider these factors when working with members of such groups. Psychologists try to eliminate the effect on their work of biases based on those factors, and they do not knowingly participate in or condone activities of others based upon such prejudices.

Contemporary Perspectives

As cross-cultural and multicultural psychology continue to gain momentum within the social sciences, many scholars have identified common barriers to effectively and ethically conduct research with diverse groups. Amer and Bagasra (2013) conducted a systematic literature review (that is, they reviewed all scholarly articles and synthesized patterns across these papers) on psychology research on Muslim Americans. Many of their observations about this collection of studies can be applied to conducting research with marginalized groups in general. They first identified common problems in how researchers conceptualize their target populations and recruitment of participants. This included (1) assuming cultural groups are monolithic, when often led to faulty recruitment strategies, and (2) a failure to understand why potential participants are hesitant to participate in psychological studies.

Problem 1: Assuming Cultural Groups are Monolithic

Amer and Bagasra (2013) noted that most scholars assumed Muslim Americans behaved in specific ways. In addition to conflating religious and ethnic identities (something unfortunately very common when studying persons with Middle Eastern/North African and/or Muslim backgrounds; Abu-Ras et al., 2008), many researchers assumed all Muslim Americans would be regular mosque-goers. In the U.S., many people (70.6%; Pew Research Center, 2016) identify as Christian, though most people are not surprised to hear that a large portion of U.S. Christians only attend church services a few times a year. Thus, U.S. Christians are recognized as having varying levels of religious commitment and service attendance. The same should be true of Muslim Americans, but many researchers rely on reaching out to local mosques to recruit participants. Thus, samples may be limited to Muslim Americans who attend services more regularly and therefore identify as more highly religious. This skews the data and makes it difficult to generalize findings to all Muslim Americans. Certainly, if a political pollster only collected data on political leanings from people living in Los Angeles and New York City, many would agree immediately that the data were biased!

The tendency to regard cultural groups as monolithic – that everyone must behave in the same way – expands beyond religious affiliation. For instance, researchers studying Latinx (Latino/a) populations must be careful about who is in their sample and, therefore, for whom the results might apply. For example, recruiting a sample of third-generation Colombian Americans living in a suburb on the west coast probably doesn’t generalize well to a group of recent immigrants from Mexico settling on the east coast. Researchers must consider levels of acculturation and immigration status, national origin, language, and current location (e.g., does the current location have anti-immigrant laws in place?).

Problem #2: Not exploring – and appreciating – why people are hesitant to be participants

After 9/11, there was a surge of research on Muslim Americans’ experiences (Amer & Bagasra). However, there was also a tremendous surge of Islamophobia and xenophobia as other Americans scapegoated Muslim and Middle Eastern persons for the terrorist attack. Due to this, and the history of social science being used to justify prejudice, many Muslim Americans were hesitant to participate in studies: many were concerned that their answers to questions about mental health, substance abuse, and other sensitive information might be used against them in the public sphere (Amer & Bagasra, 2013).

This 9/11 example points to two things that make people reluctant to engage in psychological research. First, negative public and media depictions of cultural groups mean that some members of these groups feel a need to protect their group’s reputation, by not disclosing various psychological struggles to researchers (Barkdull et al., 2011). Second, many cultural groups – regardless of whether they are experiencing prejudice – see mental illness, substance abuse, and other sensitive pieces of information (e.g., marital difficulties, etc.) as private and stigmatizing experiences that should not be shared with non-family members (Aroian et al., 2009). Thus, people who do choose to participate in these studies are likely not representative of the entire cultural group in question.

Culturally-Responsive Approaches to Research

Amer and Bagasra (2013), among many others, have suggested alternative approaches to engaging in research with diverse groups. An increasingly popular framework is called community-based participatory action research (CPAR; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2008). This framework addresses the entire research process – from developing the initial research questions through how the data and findings are reported.

Developing Research Questions with CPAR

There is a tendency for researchers to develop their research questions without actually consulting the population in question. CPAR encourages researchers to include members of the target population in the development of the questions being asked. Sometimes, the population – community – in question may not even find the study topic to be relevant or most important to their daily lives. Or, the community may identify additional questions or ask questions in a different way, based on their experiences, language, and cultural concepts. Not only does including the community in developing research questions give the community autonomy and respect (APA ethics principles), it also ensures that the community is interested in and committed to the study.

Study Materials & Recruitment with CPAR

How do researchers include the community when they develop or select their measures and procedures for study? For example, if a research team wishes to use a survey – does the survey wording capture the community’s experience? Is it in the language or dialect that is most accessible to the community? CPAR recommends researchers use focus groups with community members to review potential survey measures and adapt the measures accordingly.

Similarly, focus groups with the community can be useful for identifying the most effective and ethical recruitment strategy for study participation. How will data be collected? Do community members have regular access to the Internet, or is the phone or face-to-face more effective (or more culturally valued)? Focus groups also ensure that the researchers and community members form a relationship that prioritizes the community’s needs and experiences. Imagine a researcher with no tie to a particular cultural community attempting to recruit people for a face-to-face interview on domestic violence – this would not be successful, and may make community members feel targeted or tokenized.

Sometimes researchers may identify a gatekeeper – usually a community leader (or in the case of faith groups, a religious leader) – who is respected and influential within their community. If a gatekeeper demonstrates support for the research being conducted, usually the community will be more willing to engage. This means taking the time to develop a relationship with community leaders where the researchers value and see the community leaders as part of their research team.

Analyzing and Distributing Results with CPAR

Once the data are collected, researchers should meet with the community and share the study findings. At this point, researchers should invite community feedback on what was found and include this feedback when they write up their reports. Often, this is more important if the study included interviews – where community members’ words may be misconstrued during analysis. When researchers publish their data and findings, they should consider how they are discussing the community in question: are they using person-first language? Are they continuing to frame the study questions in a way that aligns with the community’s needs and values?

Conclusions

Psychological science has made significant gains when it comes to studying and working with diverse groups. One of the biggest gains is the diversification of psychological scholars – having diverse voices asking research questions makes those research questions more culturally relevant and responsive. However, the field has a long way to go in this regard, as there are many barriers for women and people of color in academic psychology and research (Howe-Walsh & Turnbull, 2016; Williams, 2019). The APA will regularly update and release guidelines for working with diverse groups to address some of these issues.

Researchers need to understand the history of social science research in order to appreciate why particular groups may be skeptical of psychological science. Researchers also need to be aware of current, ongoing social issues and medial portrayals of various cultural groups as this influences how members of these groups may engage with research. Finally, researchers – and consumers of research (including you!) – need to critically evaluate whether their approaches to science are community-inclusive, affirming, and empowering.

References

Abu-Ras, W., Gheith, A., & Cournos, F. (2008). The imam’s role in mental health promotion: A study at 22 mosques in New York City’s Muslim community. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 3(2), 155–176. The Imam’s Role in Mental Health Promotion: A Study at 22 Mosques in New York City’s Muslim Community

Amer, M. M., & Bagasra, A. (2013). Psychological research with Muslim Americans in the age of Islamophobia: Trends, challenges, and recommendations. American Psychologist, 68(3), 134-144. Psychological research with Muslim Americans in the age of Islamophobia: Trends, challenges, and recommendations.

American Psychological Association. (2002). Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct. American Psychologist, 57(12), 1060–1073. Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct.

Aroian, K., Hough, E. S., Templin, T. N., Kulwicki, A., Ramaswamy, V., & Katz, A. (2009). A model of mother–child adjustment in Arab Muslim immigrants to the US. Social Science & Medicine, 69(9), 1377–1386. A model of mother–child adjustment in Arab Muslim immigrants to the US

Barkdull, C., Khaja, K., Queiro-Tajalli, I., Swart, A., Cunningham, D., & Dennis, S. (2011). Experiences of Muslims in four Western countries post—9/11. Affilia: Journal of Women & Social Work, 26(2), 139–153. Experiences of Muslims in Four Western Countries Post—9/11

Ellis, A. (1993). Changing RET to REBT. The Behavior Therapist, 16, 257-258.

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). Most people are not WEIRD. Nature, 466(7302), 29-29. Most people are not WEIRD

Herrnstein, R. J., & Murray, C. A. (1994). The bell curve: Intelligence and class structure in American life. Free Press.

Howe-Walsh, L., & Turnbull, S. (2016). Barriers to women leaders in academia: tales from science and technology. Studies in Higher Education, 41(3), 415-428. Barriers to women leaders in academia: tales from science and technology

Minkler, M., & Wallerstein, N. (2008). Introduction to community-based participatory research: new issues and emphases. Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes, 5-23.

Pew Research Center (2016). Religious Landscape Study. Retrieved from Pew Research Center, Religious Landscape Study

Vieten, C., Scammell, S., Pilato, R., Ammondson, I., Pargament, K. I., & Lukoff, D. (2013). Spiritual and religious competencies for psychologists. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 5(3), 129. Spiritual and religious competencies for psychologists.

Williams, M. T. (2019). Adverse racial climates in academia: Conceptualization, interventions, and call to action. New ideas in Psychology, 55, 58-67. Adverse racial climates in academia: Conceptualization, interventions, and call to action

Media Attributions

- clay-banks-iz_L6KnDAys-unsplash © Clay Banks

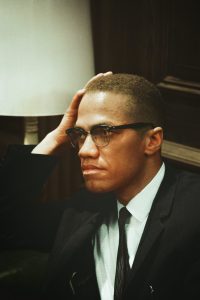

- unseen-histories-37tjLuKnBRs-unsplash © Original black and white negative by Marion S. Trikosko. Taken March 26th, 1964, Washington D.C, United States (@libraryofcongress). Colorized by Jordan J. Lloyd. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 https://www.loc.gov/item/2003688131/

- US Census 2020 Question