Chapter 11: Personality

Introduction

Three months before William Jefferson Blythe III was born, his father died in a car accident. He was raised by his mother, Virginia Dell, and grandparents, in Hope, Arkansas. When he turned 4, his mother married Roger Clinton, Jr., an alcoholic who was physically abusive to William’s mother. Six years later, Virginia gave birth to another son, Roger. William, who later took the last name Clinton from his stepfather, became the 42nd president of the United States. While Bill Clinton was making his political ascendance, his half- brother, Roger Clinton, was arrested numerous times for drug charges, including possession, conspiracy to distribute cocaine, and driving under the influence, serving time in jail. Two brothers, raised by the same people, took radically different paths in their lives. Why did they make the choices they did? What internal forces shaped their decisions? Personality psychology can help us answer these questions and more.

What is Personality

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define personality

- Describe early theories about personality development

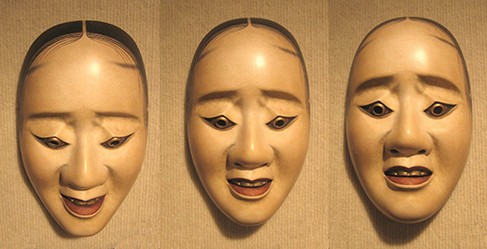

Personality refers to the long-standing traits and patterns that propel individuals to consistently think, feel, and behave in specific ways. Our personality is what makes us unique individuals. Each person has an idiosyncratic pattern of enduring, long-term characteristics and a manner in which he or she interacts with other individuals and the world around them. Our personalities are thought to be long term, stable, and not easily changed. The word personality comes from the Latin word persona. In the ancient world, a persona was a mask worn by an actor. While we tend to think of a mask as being worn to conceal one’s identity, the theatrical mask was originally used to either represent or project a specific personality trait of a character (Figure 11.2).

Figure 11.2 Happy, sad, impatient, shy, fearful, curious, helpful. What characteristics describe your personality?

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES

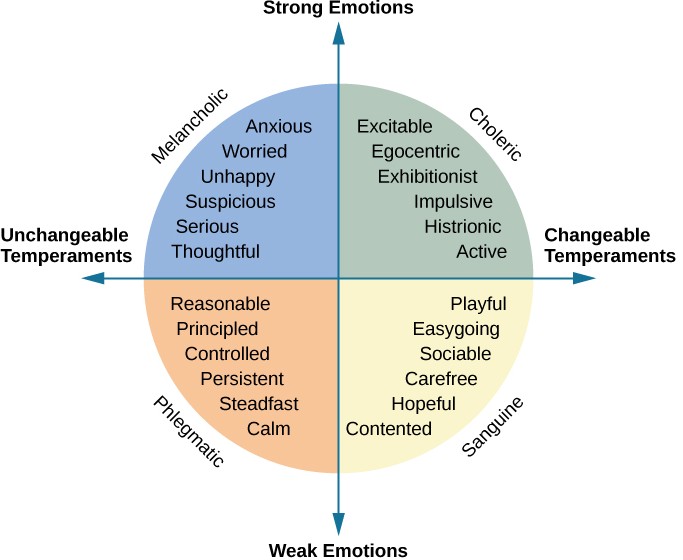

The concept of personality has been studied for at least 2,000 years, beginning with Hippocrates in 370 BCE (Fazeli, 2012). Hippocrates theorized that personality traits and human behaviors are based on four separate temperaments associated with four fluids (“humors”) of the body: choleric temperament (yellow bile from the liver), melancholic temperament (black bile from the kidneys), sanguine temperament (red blood from the heart), and phlegmatic temperament (white phlegm from the lungs) (Clark & Watson, 2008; Eysenck & Eysenck, 1985; Lecci & Magnavita, 2013; Noga, 2007). Centuries later, the influential Greek physician and philosopher Galen built on Hippocrates’s theory, suggesting that both diseases and personality differences could be explained by imbalances in the humors and that each person exhibits one of the four temperaments. For example, the choleric person is passionate, ambitious, and bold; the melancholic person is reserved, anxious, and unhappy; the sanguine person is joyful, eager, and optimistic; and the phlegmatic person is calm, reliable, and thoughtful (Clark & Watson, 2008; Stelmack & Stalikas, 1991). Galen’s theory was prevalent for over 1,000 years and continued to be popular through the Middle Ages.

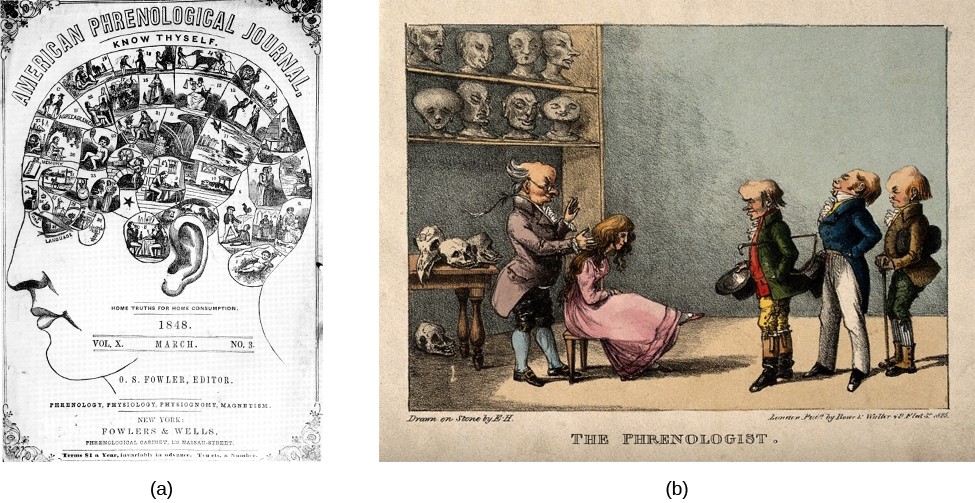

In 1780, Franz Gall, a German physician, proposed that the distances between bumps on the skull reveal a person’s personality traits, character, and mental abilities (Figure 11.3). According to Gall, measuring these distances revealed the sizes of the brain areas underneath, providing information that could be used to determine whether a person was friendly, prideful, murderous, kind, good with languages, and so on. Initially, phrenology was very popular; however, it was soon discredited for lack of empirical support and has long been relegated to the status of pseudoscience (Fancher, 1979).

Figure 11.3 The pseudoscience of measuring the areas of a person’s skull is known as phrenology. (a) Gall developed a chart that depicted which areas of the skull corresponded to particular personality traits or characteristics (Hothersall, 1995). (b) An 1825 lithograph depicts Gall examining the skull of a young woman. (credit b: modification of work by Wellcome Library, London)

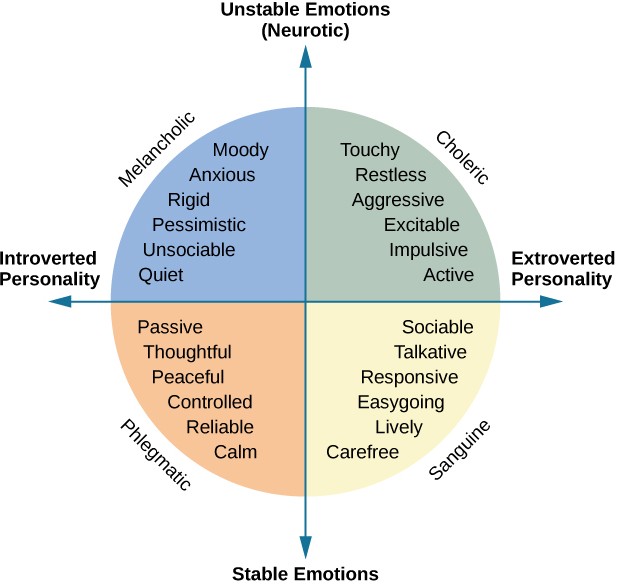

In the centuries after Galen, other researchers contributed to the development of his four primary temperament types, most prominently Immanuel Kant (in the 18th century) and psychologist Wilhelm Wundt (in the 19th century) (Eysenck, 2009; Stelmack & Stalikas, 1991; Wundt, 1874/1886) (Figure 11.4). Kant agreed with Galen that everyone could be sorted into one of the four temperaments and that there was no overlap between the four categories (Eysenck, 2009). He developed a list of traits that could be used to describe the personality of a person from each of the four temperaments. However, Wundt suggested that a better description of personality could be achieved using two major axes: emotional/ nonemotional and changeable/unchangeable. The first axis separated strong from weak emotions (the melancholic and choleric temperaments from the phlegmatic and sanguine). The second axis divided the changeable temperaments (choleric and sanguine) from the unchangeable ones (melancholic and phlegmatic) (Eysenck, 2009).

Figure 11.4 Developed from Galen’s theory of the four temperaments, Kant proposed trait words to describe each temperament. Wundt later suggested the arrangement of the traits on two major axes.

Sigmund Freud’s psychodynamic perspective of personality was the first comprehensive theory of personality, explaining a wide variety of both normal and abnormal behaviors. According to Freud, unconscious drives influenced by sex and aggression, along with childhood sexuality, are the forces that influence our personality. Freud attracted many followers who modified his ideas to create new theories about personality. These theorists, referred to as neo-Freudians, generally agreed with Freud that childhood experiences matter, but they reduced the emphasis on sex and focused more on the social environment and effects of culture on personality. The perspective of personality proposed by Freud and his followers was the dominant theory of personality for the first half of the 20th century.

Other major theories then emerged, including the learning, humanistic, biological, evolutionary, trait, and cultural perspectives. In this chapter, we will explore these various perspectives on personality in depth.

LINK TO LEARNINGView this video for a brief overview (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/mandela) ofsome of the psychological perspectives on personality.

Freud and Psychodynamic Perspective

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the assumptions of the psychodynamic perspective on personality development

- Define and describe the nature and function of the id, ego, and superego

- Define and describe the defense mechanisms

- Define and describe the psychosexual stages of personality development

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) is probably the most controversial and misunderstood psychological theorist. When reading Freud’s theories, it is important to remember that he was a medical doctor, not a psychologist. There was no such thing as a degree in psychology at the time that he received his education, which can help us understand some of the controversy over his theories today. However, Freud was the first to systematically study and theorize the workings of the unconscious mind in the manner that we associate with modern psychology.

In the early years of his career, Freud worked with Josef Breuer, a Viennese physician. During this time, Freud became intrigued by the story of one of Breuer’s patients, Bertha Pappenheim, who was referred to by the pseudonym Anna O. (Launer, 2005). Anna O. had been caring for her dying father when she began to experience symptoms such as partial paralysis, headaches, blurred vision, amnesia, and hallucinations (Launer, 2005). In Freud’s day, these symptoms were commonly referred to as hysteria. Anna O. turned to Breuer for help. He spent 2 years (1880–1882) treating Anna O. and discovered that allowing her to talk about her experiences seemed to bring some relief of her symptoms. Anna O. called his treatment the “talking cure” (Launer, 2005). Despite the fact the Freud never met Anna O., her story served as the basis for the 1895 book, Studies on Hysteria, which he co-authored with Breuer. Based on Breuer’s description of Anna O.’s treatment, Freud concluded that hysteria was the result of sexual abuse in childhood and that these traumatic experiences had been hidden from consciousness. Breuer disagreed with Freud, which soon ended their work together. However, Freud continued to work to refine talk therapy and build his theory on personality.

LEVELS OF CONSCIOUSNESS

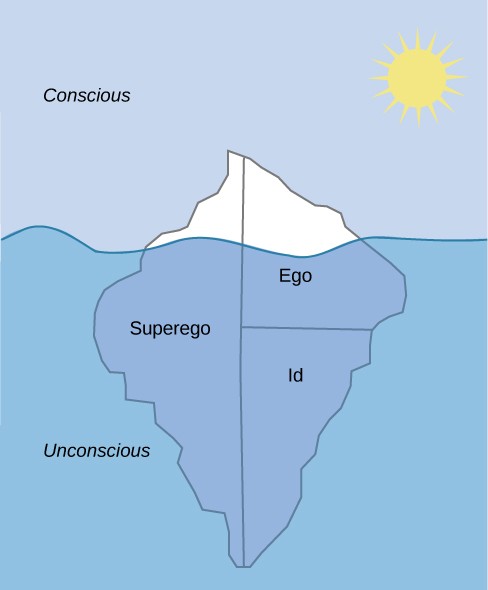

To explain the concept of conscious versus unconscious experience, Freud compared the mind to an iceberg (Figure11.5). He said that only about one-tenth of our mind is conscious, and the rest of our mind is unconscious. Our unconscious refers to that mental activity of which we are unaware and are unable to access (Freud, 1923). According to Freud, unacceptable urges and desires are kept in our unconscious through a process called repression. For example, we sometimes say things that we don’t intend to say by unintentionally substituting another word for the one we meant. You’ve probably heard of a Freudian slip, the term used to describe this. Freud suggested that slips of the tongue are actually sexual or aggressive urges, accidentally slipping out of our unconscious. Speech errors such as this are quite common. Seeing them as a reflection of unconscious desires, linguists today have found that slips of the tongue tend to occur when we are tired, nervous, or not at our optimal level of cognitive functioning (Motley, 2002).

Figure 11.5 Freud believed that we are only aware of a small amount of our mind’s activities and that most of it remains hidden from us in our unconscious. The information in our unconscious affects our behavior, although we are unaware of it.

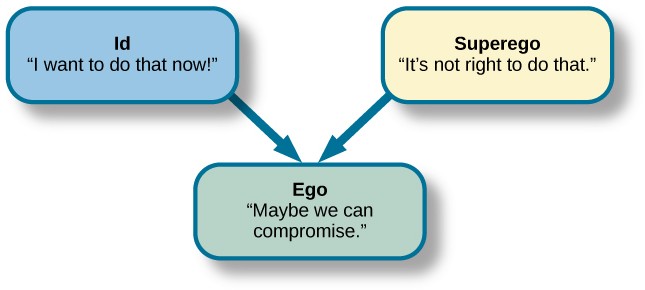

According to Freud, our personality develops from a conflict between two forces: our biological aggressive and pleasure-seeking drives versus our internal (socialized) control over these drives. Our personality is the result of our efforts to balance these two competing forces. Freud suggested that we can understand this by imagining three interacting systems within our minds. He called them the id, ego, and superego (Figure11.6).

Figure 11.6 The job of the ego, or self, is to balance the aggressive/pleasure-seeking drives of the id with the moral control of the superego.

The unconscious id contains our most primitive drives or urges, and is present from birth. It directs impulses for hunger, thirst, and sex. Freud believed that the id operates on what he called the “pleasure principle,” in which the id seeks immediate gratification. Through social interactions with parents and others in a child’s environment, the ego and superego develop to help control the id. The superego develops as a child interacts with others, learning the social rules for right and wrong. The superego acts

as our conscience; it is our moral compass that tells us how we should behave. It strives for perfection and judges our behavior, leading to feelings of pride or—when we fall short of the ideal—feelings of guilt. In contrast to the instinctual id and the rule-based superego, the ego is the rational part of our personality. It’s what Freud considered to be the self, and it is the part of our personality that is seen by others. Its job is to balance the demands of the id and superego in the context of reality; thus, it operates on what Freud called the “reality principle.” The ego helps the id satisfy its desires in a realistic way.

The id and superego are in constant conflict, because the id wants instant gratification regardless of the consequences, but the superego tells us that we must behave in socially acceptable ways. Thus, the ego’s job is to find the middle ground. It helps satisfy the id’s desires in a rational way that will not lead us to feelings of guilt. According to Freud, a person who has a strong ego, which can balance the demands of the id and the superego, has a healthy personality. Freud maintained that imbalances in the system can lead to neurosis (a tendency to experience negative emotions), anxiety disorders, or unhealthy behaviors. For example, a person who is dominated by their id might be narcissistic and impulsive. A person with a dominant superego might be controlled by feelings of guilt and deny themselves even socially acceptable pleasures; conversely, if the superego is weak or absent, a person might become a psychopath. An overly dominant superego might be seen in an over-controlled individual whose rational grasp on reality is so strong that they are unaware of their emotional needs, or, in a neurotic who is overly defensive (overusing ego defense mechanisms).

DEFENSE MECHANISMS

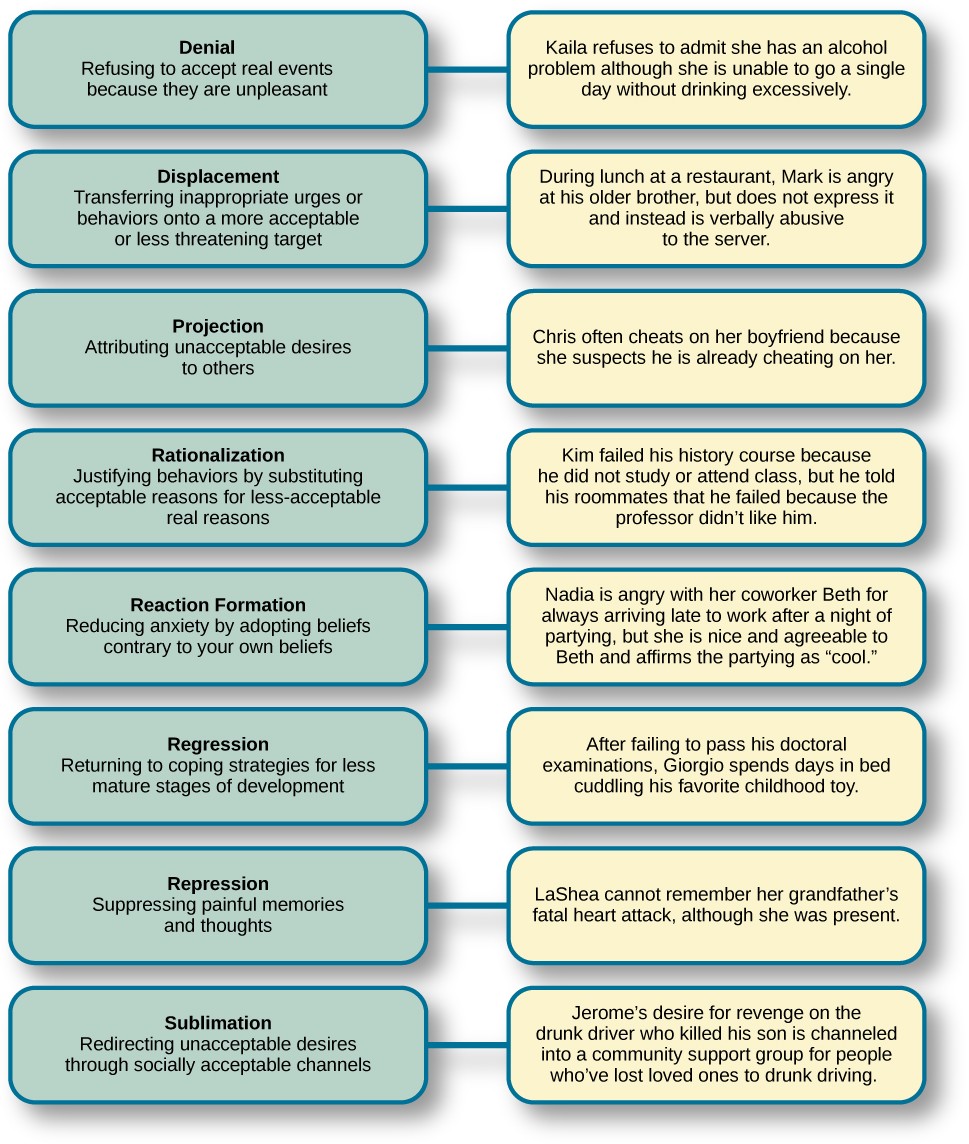

Freud believed that feelings of anxiety result from the ego’s inability to mediate the conflict between the id and superego. When this happens, Freud believed that the ego seeks to restore balance through various protective measures known as defense mechanisms (Figure 11.7). When certain events, feelings, or yearnings cause an individual anxiety, the individual wishes to reduce that anxiety. To do that, the individual’s unconscious mind uses ego defense mechanisms, unconscious protective behaviors that aim to reduce anxiety. The ego, usually conscious, resorts to unconscious strivings to protect the ego from being overwhelmed by anxiety. When we use defense mechanisms, we are unaware that we are using them. Further, they operate in various ways that distort reality. According to Freud, we all use ego defense mechanisms.

Figure 11.7 Defense mechanisms are unconscious protective behaviors that work to reduce anxiety.

While everyone uses defense mechanisms, Freud believed that overuse of them may be problematic. For example, let’s say Joe Smith is a high school football player. Deep down, Joe feels sexually attracted to males. His conscious belief is that being gay is immoral and that if he were gay, his family would disown him and he would be ostracized by his peers. Therefore, there is a conflict between his conscious beliefs (being gay is wrong and will result in being ostracized) and his unconscious urges (attraction to males). The idea that he might be gay causes Joe to have feelings of anxiety. How can he decrease his anxiety? Joe

may find himself acting very “macho,” making gay jokes, and picking on a school peer who is gay. This way, Joe’s unconscious impulses are further submerged.

There are several different types of defense mechanisms. For instance, in repression, anxiety-causing memories from consciousness are blocked. As an analogy, let’s say your car is making a strange noise, but because you do not have the money to get it fixed, you just turn up the radio so that you no longer hear the strange noise. Eventually you forget about it. Similarly, in the human psyche, if a memory is too overwhelming to deal with, it might be repressed and thus removed from conscious awareness (Freud, 1920). This repressed memory might cause symptoms in other areas.

Another defense mechanism is reaction formation, in which someone expresses feelings, thoughts, and behaviors opposite to their inclinations. In the above example, Joe made fun of a homosexual peer while himself being attracted to males. In regression, an individual acts much younger than their age. For example, a four-year-old child who resents the arrival of a newborn sibling may act like a baby and revert to drinking out of a bottle. In projection, a person refuses to acknowledge her own unconscious feelings and instead sees those feelings in someone else. Other defense mechanisms include rationalization, displacement, and sublimation.

LINK TO LEARNINGWatch this video (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/defmech) for a review of Freud’sdefense mechanisms.

STAGES OF PSYCHOSEXUAL DEVELOPMENT

Freud believed that personality develops during early childhood: Childhood experiences shape our personalities as well as our behavior as adults. He asserted that we develop via a series of stages during childhood. Each of us must pass through these childhood stages, and if we do not have the proper nurturing and parenting during a stage, we will be stuck, or fixated, in that stage, even as adults.

In each psychosexual stage of development, the child’s pleasure-seeking urges, coming from the id, are focused on a different area of the body, called an erogenous zone. The stages are oral, anal, phallic, latency, and genital (Table11.1).

Freud’s psychosexual development theory is quite controversial. To understand the origins of the theory, it is helpful to be familiar with the political, social, and cultural influences of Freud’s day in Vienna at the turn of the 20th century. During this era, a climate of sexual repression, combined with limited understanding and education surrounding human sexuality, heavily influenced Freud’s perspective. Given that sex was a taboo topic, Freud assumed that negative emotional states (neuroses) stemmed from suppression of unconscious sexual and aggressive urges. For Freud, his own recollections and interpretations of patients’ experiences and dreams were sufficient proof that psychosexual stages were universal events in early childhood.

|

Table 11.1 Freud’s Stages of Psychosexual Development |

||||

|

Stage |

Age (years) |

Erogenous Zone |

Major Conflict |

Adult Fixation Example |

|

Oral |

0–1 |

Mouth |

Weaning off breast or bottle |

Smoking, overeating |

|

Anal |

1–3 |

Anus |

Toilet training |

Neatness, messiness |

|

Phallic |

3–6 |

Genitals |

Oedipus/Electra complex |

Vanity, overambition |

|

Latency |

6–12 |

None |

None |

None |

|

Genital |

12+ |

Genitals |

None |

None |

Oral Stage

In the oral stage (birth to 1 year), pleasure is focused on the mouth. Eating and the pleasure derived from sucking (nipples, pacifiers, and thumbs) play a large part in a baby’s first year of life. At around 1 year of age, babies are weaned from the bottle or breast, and this process can create conflict if not handled properly by caregivers. According to Freud, an adult who smokes, drinks, overeats, or bites her nails is fixated in the oral stage of her psychosexual development; she may have been weaned too early or too late, resulting in these fixation tendencies, all of which seek to ease anxiety.

Anal Stage

After passing through the oral stage, children enter what Freud termed the anal stage (1–3 years). In this stage, children experience pleasure in their bowel and bladder movements, so it makes sense that the conflict in this stage is over toilet training. Freud suggested that success at the anal stage depended on how parents handled toilet training. Parents who offer praise and rewards encourage positive results and can help children feel competent. Parents who are harsh in toilet training can cause a child to become fixated at the anal stage, leading to the development of an anal-retentive personality. The anal-retentive personality is stingy and stubborn, has a compulsive need for order and neatness, and might be considered a perfectionist. If parents are too lenient in toilet training, the child might also become fixated and display an anal-expulsive personality. The anal-expulsive personality is messy, careless, disorganized, and prone to emotional outbursts.

Phallic Stage

Freud’s third stage of psychosexual development is the phallic stage (3–6 years), corresponding to the age when children become aware of their bodies and recognize the differences between boys and girls. The erogenous zone in this stage is the genitals. Conflict arises when the child feels a desire for the opposite- sex parent, and jealousy and hatred toward the same-sex parent. For boys, this is called the Oedipus complex, involving a boy’s desire for his mother and his urge to replace his father who is seen as a rival for the mother’s attention. At the same time, the boy is afraid his father will punish him for his feelings, so he experiences castration anxiety. The Oedipus complex is successfully resolved when the boy begins to identify with his father as an indirect way to have the mother. Failure to resolve the Oedipus complex may result in fixation and development of a personality that might be described as vain and overly ambitious.

Girls experience a comparable conflict in the phallic stage—the Electra complex. The Electra complex, while often attributed to Freud, was actually proposed by Freud’s protégé, Carl Jung (Jung & Kerenyi, 1963). A girl desires the attention of her father and wishes to take her mother’s place. Jung also said that girls are angry with the mother for not providing them with a penis—hence the term penis envy. While

Freud initially embraced the Electra complex as a parallel to the Oedipus complex, he later rejected it, yet it remains as a cornerstone of Freudian theory, thanks in part to academics in the field (Freud, 1931/1968; Scott, 2005).

Latency Period

Following the phallic stage of psychosexual development is a period known as the latency period (6 years to puberty). This period is not considered a stage, because sexual feelings are dormant as children focus on other pursuits, such as school, friendships, hobbies, and sports. Children generally engage in activities with peers of the same sex, which serves to consolidate a child’s gender-role identity.

Genital Stage

The final stage is the genital stage (from puberty on). In this stage, there is a sexual reawakening as the incestuous urges resurface. The young person redirects these urges to other, more socially acceptable partners (who often resemble the other-sex parent). People in this stage have mature sexual interests, which for Freud meant a strong desire for the opposite sex. Individuals who successfully completed the previous stages, reaching the genital stage with no fixations, are said to be well-balanced, healthy adults.

While most of Freud’s ideas have not found support in modern research, we cannot discount the contributions that Freud has made to the field of psychology. It was Freud who pointed out that a large part of our mental life is influenced by the experiences of early childhood and takes place outside of our conscious awareness; his theories paved the way for others.

Neo-Freudians: Adler, Erikson, Jung, and Horney

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Discuss the concept of the inferiority complex

- Discuss the core differences between Erikson’s and Freud’s views on personality

- Discuss Jung’s ideas of the collective unconscious and archetypes

- Discuss the work of Karen Horney, including her revision of Freud’s “penis envy”

Freud attracted many followers who modified his ideas to create new theories about personality. These theorists, referred to as neo-Freudians, generally agreed with Freud that childhood experiences matter, but deemphasized sex, focusing more on the social environment and effects of culture on personality. Four notable neo-Freudians include Alfred Adler, Erik Erikson, Carl Jung (pronounced “Yoong”), and Karen Horney (pronounced “HORN-eye”).

ALFRED ADLER

Alfred Adler, a colleague of Freud’s and the first president of the Vienna Psychoanalytical Society (Freud’s inner circle of colleagues), was the first major theorist to break away from Freud (Figure 11.8). He subsequently founded a school of psychology called individual psychology, which focuses on our drive to compensate for feelings of inferiority. Adler (1937, 1956) proposed the concept of the inferiority complex. An inferiority complex refers to a person’s feelings that they lack worth and don’t measure up to the standards of others or of society. Adler’s ideas about inferiority represent a major difference between his thinking and Freud’s. Freud believed that we are motivated by sexual and aggressive urges, but Adler (1930, 1961) believed that feelings of inferiority in childhood are what drive people to attempt to gain superiority and that this striving is the force behind all of our thoughts, emotions, and behaviors.

Figure 11.8 Alfred Adler proposed the concept of the inferiority complex.

Adler also believed in the importance of social connections, seeing childhood development emerging through social development rather than the sexual stages Freud outlined. Adler noted the inter-relatedness of humanity and the need to work together for the betterment of all. He said, “The happiness of mankind lies in working together, in living as if each individual had set himself the task of contributing to the common welfare” (Adler, 1964, p. 255) with the main goal of psychology being “to recognize the equal rights and equality of others” (Adler, 1961, p. 691).

With these ideas, Adler identified three fundamental social tasks that all of us must experience: occupational tasks (careers), societal tasks (friendship), and love tasks (finding an intimate partner for a long-term relationship). Rather than focus on sexual or aggressive motives for behavior as Freud did, Adler focused on social motives. He also emphasized conscious rather than unconscious motivation, since he believed that the three fundamental social tasks are explicitly known and pursued. That is not to say that Adler did not also believe in unconscious processes—he did—but he felt that conscious processes were more important.

One of Adler’s major contributions to personality psychology was the idea that our birth order shapes our personality. He proposed that older siblings, who start out as the focus of their parents’ attention but must share that attention once a new child joins the family, compensate by becoming overachievers. The youngest children, according to Adler, may be spoiled, leaving the middle child with the opportunity to minimize the negative dynamics of the youngest and oldest children. Despite popular attention, research has not conclusively confirmed Adler’s hypotheses about birth order.

LINK TO LEARNINGOne of Adler’s major contributions to personality psychology was the idea that our birth order shapes our personality. Follow this link (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/best) to view a summary of birth order theory.

ERIK ERIKSON

As an art school dropout with an uncertain future, young Erik Erikson met Freud’s daughter, Anna Freud, while he was tutoring the children of an American couple undergoing psychoanalysis in Vienna. It was Anna Freud who encouraged Erikson to study psychoanalysis. Erikson received his diploma from the Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute in 1933, and as Nazism spread across Europe, he fled the country and immigrated to the United States that same year. As you learned when you studied lifespan development, Erikson later proposed a psychosocial theory of development, suggesting that an individual’s personality develops throughout the lifespan—a departure from Freud’s view that personality is fixed in early life.

In his theory, Erikson emphasized the social relationships that are important at each stage of personality development, in contrast to Freud’s emphasis on sex. Erikson identified eight stages, each of which represents a conflict or developmental task (Table 11.2). The development of a healthy personality and a sense of competence depend on the successful completion of each task.

|

Stage |

Age (years) |

Developmental Task |

Description |

|

1 |

0–1 |

Trust vs. mistrust |

Trust (or mistrust) that basic needs, such as nourishment and affection, will be met |

|

2 |

1–3 |

Autonomy vs. shame/doubt |

Sense of independence in many tasks develops |

|

3 |

3–6 |

Initiative vs. guilt |

Take initiative on some activities, may develop guilt when success not met or boundaries overstepped |

|

4 |

7–11 |

Industry vs. inferiority |

Develop self-confidence in abilities when competent or sense of inferiority when not |

|

5 |

12–18 |

Identity vs. confusion |

Experiment with and develop identity and roles |

|

6 |

19–29 |

Intimacy vs. isolation |

Establish intimacy and relationships with others |

|

7 |

30–64 |

Generativity vs. stagnation |

Contribute to society and be part of a family |

|

8 |

65– |

Integrity vs. despair |

Assess and make sense of life and meaning of contributions |

CARL JUNG

Carl Jung (Figure 11.9) was a Swiss psychiatrist and protégé of Freud, who later split off from Freud and developed his own theory, which he called analytical psychology. The focus of analytical psychology is on working to balance opposing forces of conscious and unconscious thought, and experience within one’s personality. According to Jung, this work is a continuous learning process—mainly occurring in the second half of life—of becoming aware of unconscious elements and integrating them into consciousness.

Figure 11.9 Carl Jung was interested in exploring the collective unconscious.

Jung’s split from Freud was based on two major disagreements. First, Jung, like Adler and Erikson, did not accept that sexual drive was the primary motivator in a person’s mental life. Second, although Jung agreed with Freud’s concept of a personal unconscious, he thought it to be incomplete. In addition to the personal unconscious, Jung focused on the collective unconscious.

The collective unconscious is a universal version of the personal unconscious, holding mental patterns, or memory traces, which are common to all of us (Jung, 1928). These ancestral memories, which Jung called archetypes, are represented by universal themes in various cultures, as expressed through literature, art, and dreams (Jung). Jung said that these themes reflect common experiences of people the world over, such as facing death, becoming independent, and striving for mastery. Jung (1964) believed that through biology, each person is handed down the same themes and that the same types of symbols—such as the hero, the maiden, the sage, and the trickster—are present in the folklore and fairy tales of every culture. In Jung’s view, the task of integrating these unconscious archetypal aspects of the self is part of the self- realization process in the second half of life. With this orientation toward self-realization, Jung parted ways with Freud’s belief that personality is determined solely by past events and anticipated the humanistic movement with its emphasis on self-actualization and orientation toward the future.

Jung also proposed two attitudes or approaches toward life: extroversion and introversion (Jung, 1923) (Table 11.3). These ideas are considered Jung’s most important contributions to the field of personality psychology, as almost all models of personality now include these concepts. If you are an extrovert, then you are a person who is energized by being outgoing and socially oriented: You derive your energy from being around others. If you are an introvert, then you are a person who may be quiet and reserved, or you may be social, but your energy is derived from your inner psychic activity. Jung believed a balance between extroversion and introversion best served the goal of self-realization.

|

Introvert |

Extrovert |

|

Energized by being alone |

Energized by being with others |

|

Avoids attention |

Seeks attention |

|

Table 11.3 Introverts and Extroverts |

|

|

Introvert |

Extrovert |

|

Speaks slowly and softly |

Speaks quickly and loudly |

|

Thinks before speaking |

Thinks out loud |

|

Stays on one topic |

Jumps from topic to topic |

|

Prefers written communication |

Prefers verbal communication |

|

Pays attention easily |

Distractible |

|

Cautious |

Acts first, thinks later |

Another concept proposed by Jung was the persona, which he referred to as a mask that we adopt. According to Jung, we consciously create this persona; however, it is derived from both our conscious experiences and our collective unconscious. What is the purpose of the persona? Jung believed that it is a compromise between who we really are (our true self) and what society expects us to be. We hide those parts of ourselves that are not aligned with society’s expectations.

LINK TO LEARNINGJung’s view of extroverted and introverted types serves as a basis of the Myers- Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI). This questionnaire describes a person’s degree of introversion versus extroversion, thinking versus feeling, intuition versus sensation, and judging versus perceiving. This site (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/myersbriggs) provides a modified questionnaire based on the MBTI.

CONNECT THE CONCEPTS CONNECT THE CONCEPTSAre Archetypes Genetically Based?Jung proposed that human responses to archetypes are similar to instinctual responses in animals. One criticism of Jung is that there is no evidence that archetypes are biologically based or similar to animal instincts (Roesler, 2012). Jung formulated his ideas about 100 years ago, and great advances have been made in the field of genetics since that time. We’ve found that human babies are born with certain capacities, including the ability to acquire language. However, we’ve also found that symbolic information (such as archetypes) is not encoded on the genome and that babies cannot decode symbolism, refuting the idea of a biological basis to archetypes. Rather than being seen as purely biological, more recent research suggests that archetypes emerge directly from our experiences and are reflections of linguistic or cultural characteristics (Young-Eisendrath, 1995). Today, most Jungian scholars believe that the collective unconscious and archetypes are based on both innate and environmental influences, with the differences being in the role and degree of each (Sotirova-Kohli et al., 2013).

KAREN HORNEY

Karen Horney was one of the first women trained as a Freudian psychoanalyst. During the Great Depression, Horney moved from Germany to the United States, and subsequently moved away from

Freud’s teachings. Like Jung, Horney believed that each individual has the potential for self-realization and that the goal of psychoanalysis should be moving toward a healthy self rather than exploring early childhood patterns of dysfunction. Horney also disagreed with the Freudian idea that girls have penis envy and are jealous of male biological features. According to Horney, any jealousy is most likely culturally based, due to the greater privileges that males often have, meaning that the differences between men’s and women’s personalities are culturally based, not biologically based. She further suggested that men have womb envy, because they cannot give birth.

Horney’s theories focused on the role of unconscious anxiety. She suggested that normal growth can be blocked by basic anxiety stemming from needs not being met, such as childhood experiences of loneliness and/or isolation. How do children learn to handle this anxiety? Horney suggested three styles of coping (Table 11.4). The first coping style, moving toward people, relies on affiliation and dependence. These children become dependent on their parents and other caregivers in an effort to receive attention and affection, which provides relief from anxiety (Burger, 2008). When these children grow up, they tend to use this same coping strategy to deal with relationships, expressing an intense need for love and acceptance (Burger, 2008). The second coping style, moving against people, relies on aggression and assertiveness. Children with this coping style find that fighting is the best way to deal with an unhappy home situation, and they deal with their feelings of insecurity by bullying other children (Burger, 2008). As adults, people with this coping style tend to lash out with hurtful comments and exploit others (Burger, 2008). The third coping style, moving away from people, centers on detachment and isolation. These children handle their anxiety by withdrawing from the world. They need privacy and tend to be self-sufficient. When these children are adults, they continue to avoid such things as love and friendship, and they also tend to gravitate toward careers that require little interaction with others (Burger, 2008).

|

Coping Style |

Description |

Example |

|

Moving toward people |

Affiliation and dependence |

Child seeking positive attention and affection from parent; adult needing love |

|

Moving against people |

Aggression and manipulation |

Child fighting or bullying other children; adult who is abrasive and verbally hurtful, or who exploits others |

|

Moving away from people |

Detachment and isolation |

Child withdrawn from the world and isolated; adult loner |

Horney believed these three styles are ways in which people typically cope with day-to-day problems; however, the three coping styles can become neurotic strategies if they are used rigidly and compulsively, leading a person to become alienated from others.

Learning Approaches

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the behaviorist perspective on personality

- Describe the cognitive perspective on personality

- Describe the social cognitive perspective on personality

In contrast to the psychodynamic approaches of Freud and the neo-Freudians, which relate personality to

inner (and hidden) processes, the learning approaches focus only on observable behavior. This illustrates one significant advantage of the learning approaches over psychodynamics: Because learning approaches involve observable, measurable phenomena, they can be scientifically tested.

THE BEHAVIORAL PERSPECTIVE

Behaviorists do not believe in biological determinism: They do not see personality traits as inborn. Instead, they view personality as significantly shaped by the reinforcements and consequences outside of the organism. In other words, people behave in a consistent manner based on prior learning. B. F. Skinner, a strict behaviorist, believed that environment was solely responsible for all behavior, including the enduring, consistent behavior patterns studied by personality theorists.

As you may recall from your study on the psychology of learning, Skinner proposed that we demonstrate consistent behavior patterns because we have developed certain response tendencies (Skinner, 1953). In other words, we learn to behave in particular ways. We increase the behaviors that lead to positive consequences, and we decrease the behaviors that lead to negative consequences. Skinner disagreed with Freud’s idea that personality is fixed in childhood. He argued that personality develops over our entire life, not only in the first few years. Our responses can change as we come across new situations; therefore, we can expect more variability over time in personality than Freud would anticipate. For example, consider a young woman, Greta, a risk taker. She drives fast and participates in dangerous sports such as hang gliding and kiteboarding. But after she gets married and has children, the system of reinforcements and punishments in her environment changes. Speeding and extreme sports are no longer reinforced, so she no longer engages in those behaviors. In fact, Greta now describes herself as a cautious person.

THE SOCIAL-COGNITIVE PERSPECTIVE

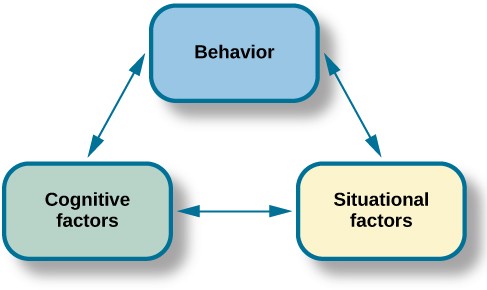

Albert Bandura agreed with Skinner that personality develops through learning. He disagreed, however, with Skinner’s strict behaviorist approach to personality development, because he felt that thinking and reasoning are important components of learning. He presented a social-cognitive theory of personality that emphasizes both learning and cognition as sources of individual differences in personality. In social- cognitive theory, the concepts of reciprocal determinism, observational learning, and self-efficacy all play a part in personality development.

Reciprocal Determinism

In contrast to Skinner’s idea that the environment alone determines behavior, Bandura (1990) proposed the concept of reciprocal determinism, in which cognitive processes, behavior, and context all interact, each factor influencing and being influenced by the others simultaneously (Figure 11.10). Cognitive processes refer to all characteristics previously learned, including beliefs, expectations, and personality characteristics. Behavior refers to anything that we do that may be rewarded or punished. Finally, the context in which the behavior occurs refers to the environment or situation, which includes rewarding/ punishing stimuli.

Figure 11.10 Bandura proposed the idea of reciprocal determinism: Our behavior, cognitive processes, and situational context all influence each other.

Consider, for example, that you’re at a festival and one of the attractions is bungee jumping from a bridge. Do you do it? In this example, the behavior is bungee jumping. Cognitive factors that might influence this behavior include your beliefs and values, and your past experiences with similar behaviors. Finally, context refers to the reward structure for the behavior. According to reciprocal determinism, all of these factors are in play.

Observational Learning

Bandura’s key contribution to learning theory was the idea that much learning is vicarious. We learn by observing someone else’s behavior and its consequences, which Bandura called observational learning. He felt that this type of learning also plays a part in the development of our personality. Just as we learn individual behaviors, we learn new behavior patterns when we see them performed by other people or models. Drawing on the behaviorists’ ideas about reinforcement, Bandura suggested that whether we choose to imitate a model’s behavior depends on whether we see the model reinforced or punished. Through observational learning, we come to learn what behaviors are acceptable and rewarded in our culture, and we also learn to inhibit deviant or socially unacceptable behaviors by seeing what behaviors are punished.

We can see the principles of reciprocal determinism at work in observational learning. For example, personal factors determine which behaviors in the environment a person chooses to imitate, and those environmental events in turn are processed cognitively according to other personal factors.

Self-Efficacy

Bandura (1977, 1995) has studied a number of cognitive and personal factors that affect learning and personality development, and most recently has focused on the concept of self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is our level of confidence in our own abilities, developed through our social experiences. Self-efficacy affects how we approach challenges and reach goals. In observational learning, self-efficacy is a cognitive factor that affects which behaviors we choose to imitate as well as our success in performing those behaviors.

People who have high self-efficacy believe that their goals are within reach, have a positive view of challenges seeing them as tasks to be mastered, develop a deep interest in and strong commitment to the activities in which they are involved, and quickly recover from setbacks. Conversely, people with low self- efficacy avoid challenging tasks because they doubt their ability to be successful, tend to focus on failure and negative outcomes, and lose confidence in their abilities if they experience setbacks. Feelings of self- efficacy can be specific to certain situations. For instance, a student might feel confident in her ability in English class but much less so in math class.

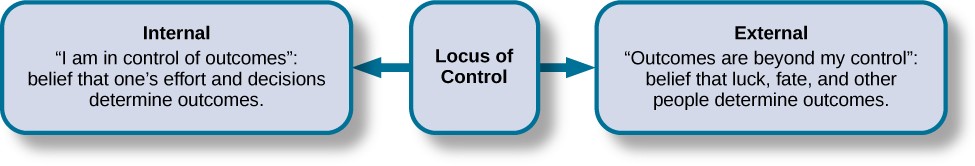

JULIAN ROTTER AND LOCUS OF CONTROL

Julian Rotter (1966) proposed the concept of locus of control, another cognitive factor that affects learning and personality development. Distinct from self-efficacy, which involves our belief in our own abilities, locus of control refers to our beliefs about the power we have over our lives. In Rotter’s view, people possess either an internal or an external locus of control (Figure 11.11). Those of us with an internal locus of control (“internals”) tend to believe that most of our outcomes are the direct result of our efforts. Those of us with an external locus of control (“externals”) tend to believe that our outcomes are outside of our control. Externals see their lives as being controlled by other people, luck, or chance. For example, say you didn’t spend much time studying for your psychology test and went out to dinner with friends instead. When you receive your test score, you see that you earned a D. If you possess an internal locus of control, you would most likely admit that you failed because you didn’t spend enough time studying and decide to study more for the next test. On the other hand, if you possess an external locus of control, you might conclude that the test was too hard and not bother studying for the next test, because you figure you will fail it anyway. Researchers have found that people with an internal locus of control perform better academically, achieve more in their careers, are more independent, are healthier, are better able to cope, and are less depressed than people who have an external locus of control (Benassi, Sweeney, & Durfour, 1988; Lefcourt, 1982; Maltby, Day, & Macaskill, 2007; Whyte, 1977, 1978, 1980).

Figure 11.11 Locus of control occurs on a continuum from internal to external.

LINK TO LEARNINGTake the Locus of Control (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/locuscontrol)questionnaire. Scores range from 0 to 13. A low score on this questionnaire indicates an internal locus of control, and a high score indicates an external locus of control.

WALTER MISCHEL AND THE PERSON-SITUATION DEBATE

Walter Mischel was a student of Julian Rotter and taught for years at Stanford, where he was a colleague of Albert Bandura. Mischel surveyed several decades of empirical psychological literature regarding trait prediction of behavior, and his conclusion shook the foundations of personality psychology. Mischel found that the data did not support the central principle of the field—that a person’s personality traits are consistent across situations. His report triggered a decades-long period of self-examination, known as the person-situation debate, among personality psychologists.

Mischel suggested that perhaps we were looking for consistency in the wrong places. He found that although behavior was inconsistent across different situations, it was much more consistent within situations—so that a person’s behavior in one situation would likely be repeated in a similar one. And as you will see next regarding his famous “marshmallow test,” Mischel also found that behavior is consistent in equivalent situations across time.

One of Mischel’s most notable contributions to personality psychology was his ideas on self-regulation.

According to Lecci & Magnavita (2013), “Self-regulation is the process of identifying a goal or set of goals and, in pursuing these goals, using both internal (e.g., thoughts and affect) and external (e.g., responses of anything or anyone in the environment) feedback to maximize goal attainment” (p. 6.3). Self-regulation is also known as will power. When we talk about will power, we tend to think of it as the ability to delay gratification. For example, Bettina’s teenage daughter made strawberry cupcakes, and they looked delicious. However, Bettina forfeited the pleasure of eating one, because she is training for a 5K race and wants to be fit and do well in the race. Would you be able to resist getting a small reward now in order to get a larger reward later? This is the question Mischel investigated in his now-classic marshmallow test.

Mischel designed a study to assess self-regulation in young children. In the marshmallow study, Mischel and his colleagues placed a preschool child in a room with one marshmallow on the table. The child was told that he could either eat the marshmallow now, or wait until the researcher returned to the room and then he could have two marshmallows (Mischel, Ebbesen & Raskoff, 1972). This was repeated with hundreds of preschoolers. What Mischel and his team found was that young children differ in their degree of self-control. Mischel and his colleagues continued to follow this group of preschoolers through high school, and what do you think they discovered? The children who had more self-control in preschool (the ones who waited for the bigger reward) were more successful in high school. They had higher SAT scores, had positive peer relationships, and were less likely to have substance abuse issues; as adults, they also had more stable marriages (Mischel, Shoda, & Rodriguez, 1989; Mischel et al., 2010). On the other hand, those children who had poor self-control in preschool (the ones who grabbed the one marshmallow) were not as successful in high school, and they were found to have academic and behavioral problems.

LINK TO LEARNINGTo learn more about the marshmallow test and view the test given to children in Columbia, follow the link below to Joachim de Posada’s TEDTalks(http://openstaxcollege.org/l/TEDPosada) video.

Today, the debate is mostly resolved, and most psychologists consider both the situation and personal factors in understanding behavior. For Mischel (1993), people are situation processors. The children in the marshmallow test each processed, or interpreted, the rewards structure of that situation in their own way. Mischel’s approach to personality stresses the importance of both the situation and the way the person perceives the situation. Instead of behavior being determined by the situation, people use cognitive processes to interpret the situation and then behave in accordance with that interpretation.

Humanistic Approaches

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Discuss the contributions of Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers to personality development

As the “third force” in psychology, humanism is touted as a reaction both to the pessimistic determinism of psychoanalysis, with its emphasis on psychological disturbance, and to the behaviorists’ view of humans passively reacting to the environment, which has been criticized as making people out to be personality- less robots. It does not suggest that psychoanalytic, behaviorist, and other points of view are incorrect but argues that these perspectives do not recognize the depth and meaning of human experience, and fail to recognize the innate capacity for self-directed change and transforming personal experiences. This

perspective focuses on how healthy people develop. One pioneering humanist, Abraham Maslow, studied people who he considered to be healthy, creative, and productive, including Albert Einstein, Eleanor Roosevelt, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and others. Maslow (1950, 1970) found that such people share similar characteristics, such as being open, creative, loving, spontaneous, compassionate, concerned for others, and accepting of themselves. When you studied motivation, you learned about one of the best- known humanistic theories, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory, in which Maslow proposes that human beings have certain needs in common and that these needs must be met in a certain order. The highest need is the need for self-actualization, which is the achievement of our fullest potential.

Another humanistic theorist was Carl Rogers. One of Rogers’s main ideas about personality regards self- concept, our thoughts and feelings about ourselves. How would you respond to the question, “Who am I?” Your answer can show how you see yourself. If your response is primarily positive, then you tend to feel good about who you are, and you see the world as a safe and positive place. If your response is mainly negative, then you may feel unhappy with who you are. Rogers further divided the self into two categories: the ideal self and the real self. The ideal self is the person that you would like to be; the real self is the person you actually are. Rogers focused on the idea that we need to achieve consistency between these two selves. We experience congruence when our thoughts about our real self and ideal self are very similar—in other words, when our self-concept is accurate. High congruence leads to a greater sense of self-worth and a healthy, productive life. Parents can help their children achieve this by giving them unconditional positive regard, or unconditional love. According to Rogers (1980), “As persons are accepted and prized, they tend to develop a more caring attitude towards themselves” (p. 116). Conversely, when there is a great discrepancy between our ideal and actual selves, we experience a state Rogers called incongruence, which can lead to maladjustment. Both Rogers’s and Maslow’s theories focus on individual choices and do not believe that biology is deterministic.

Trait Theorists

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Discuss early trait theories of Cattell and Eysenck

- Discuss the Big Five factors and describe someone who is high and low on each of the five traits

Trait theorists believe personality can be understood via the approach that all people have certain traits, or characteristic ways of behaving. Do you tend to be sociable or shy? Passive or aggressive? Optimistic or pessimistic? Moody or even-tempered? Early trait theorists tried to describe all human personality traits.

For example, one trait theorist, Gordon Allport (Allport & Odbert, 1936), found 4,500 words in the English language that could describe people. He organized these personality traits into three categories: cardinal traits, central traits, and secondary traits. A cardinal trait is one that dominates your entire personality, and hence your life—such as Ebenezer Scrooge’s greed and Mother Theresa’s altruism. Cardinal traits are not very common: Few people have personalities dominated by a single trait. Instead, our personalities typically are composed of multiple traits. Central traits are those that make up our personalities (such as loyal, kind, agreeable, friendly, sneaky, wild, and grouchy). Secondary traits are those that are not quite as obvious or as consistent as central traits. They are present under specific circumstances and include preferences and attitudes. For example, one person gets angry when people try to tickle him; another can only sleep on the left side of the bed; and yet another always orders her salad dressing on the side. And you—although not normally an anxious person—feel nervous before making a speech in front of your English class.

In an effort to make the list of traits more manageable, Raymond Cattell (1946, 1957) narrowed down the list to about 171 traits. However, saying that a trait is either present or absent does not accurately reflect a person’s uniqueness, because all of our personalities are actually made up of the same traits; we differ only in the degree to which each trait is expressed. Cattell (1957) identified 16 factors or dimensions of personality: warmth, reasoning, emotional stability, dominance, liveliness, rule-consciousness, social boldness, sensitivity, vigilance, abstractedness, privateness, apprehension, openness to change, self- reliance, perfectionism, and tension (Table 11.5). He developed a personality assessment based on these 16 factors, called the 16PF. Instead of a trait being present or absent, each dimension is scored over a continuum, from high to low. For example, your level of warmth describes how warm, caring, and nice to others you are. If you score low on this index, you tend to be more distant and cold. A high score on this index signifies you are supportive and comforting.

|

Table 11.5 Personality Factors Measured by the 16PF Questionnaire |

||

|

Factor |

Low Score |

High Score |

|

Perfectionism |

Disorganized, casual |

Organized, precise |

|

Tension |

Relaxed |

Stressed |

LINK TO LEARNINGFollow this link (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/cattell) to an assessment based on Cattell’s 16PF questionnaire to see which personality traits dominate yourpersonality.

Psychologists Hans and Sybil Eysenck were personality theorists (Figure 11.13) who focused on temperament, the inborn, genetically based personality differences that you studied earlier in the chapter. They believed personality is largely governed by biology. The Eysencks (Eysenck, 1990, 1992; Eysenck & Eysenck, 1963) viewed people as having two specific personality dimensions: extroversion/introversion and neuroticism/stability.

Figure 11.13 Hans and Sybil Eysenck believed that our personality traits are influenced by our genetic inheritance. (credit: “Sirswindon”/Wikimedia Commons)

According to their theory, people high on the trait of extroversion are sociable and outgoing, and readily connect with others, whereas people high on the trait of introversion have a higher need to be alone, engage in solitary behaviors, and limit their interactions with others. In the neuroticism/stability dimension, people high on neuroticism tend to be anxious; they tend to have an overactive sympathetic nervous system and, even with low stress, their bodies and emotional state tend to go into a flight-or-fight reaction. In contrast, people high on stability tend to need more stimulation to activate their flight-or-fight reaction and are considered more emotionally stable. Based on these two dimensions, the Eysencks’ theory divides people into four quadrants. These quadrants are sometimes compared with the four temperaments

described by the Greeks: melancholic, choleric, phlegmatic, and sanguine (Figure 11.14).

Figure 11.14 The Eysencks described two factors to account for variations in our personalities: extroversion/ introversion and emotional stability/instability.

Later, the Eysencks added a third dimension: psychoticism versus superego control (Eysenck, Eysenck & Barrett, 1985). In this dimension, people who are high on psychoticism tend to be independent thinkers, cold, nonconformists, impulsive, antisocial, and hostile, whereas people who are high on superego control tend to have high impulse control—they are more altruistic, empathetic, cooperative, and conventional (Eysenck, Eysenck & Barrett, 1985).

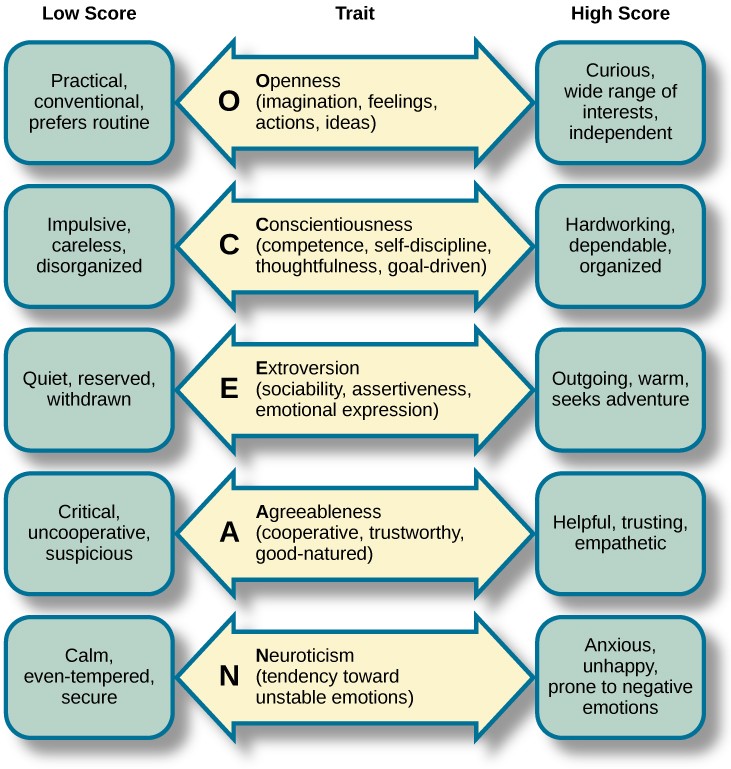

While Cattell’s 16 factors may be too broad, the Eysenck’s two-factor system has been criticized for being too narrow. Another personality theory, called the Five Factor Model, effectively hits a middle ground, with its five factors referred to as the Big Five personality traits. It is the most popular theory in personality psychology today and the most accurate approximation of the basic trait dimensions (Funder, 2001). The five traits are openness to experience, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism (Figure 11.15). A helpful way to remember the traits is by using the mnemonic OCEAN.

In the Five Factor Model, each person has each trait, but they occur along a spectrum. Openness to experience is characterized by imagination, feelings, actions, and ideas. People who score high on this trait tend to be curious and have a wide range of interests. Conscientiousness is characterized by competence, self-discipline, thoughtfulness, and achievement-striving (goal-directed behavior). People who score high on this trait are hardworking and dependable. Numerous studies have found a positive correlation between conscientiousness and academic success (Akomolafe, 2013; Chamorro-Premuzic & Furnham, 2008; Conrad & Patry, 2012; Noftle & Robins, 2007; Wagerman & Funder, 2007). Extroversion is characterized by sociability, assertiveness, excitement-seeking, and emotional expression. People who score high on this trait are usually described as outgoing and warm. Not surprisingly, people who score high on both extroversion and openness are more likely to participate in adventure and risky sports due to their curious and excitement-seeking nature (Tok, 2011). The fourth trait is agreeableness, which is the tendency to be pleasant, cooperative, trustworthy, and good-natured. People who score low on

agreeableness tend to be described as rude and uncooperative, yet one recent study reported that men who scored low on this trait actually earned more money than men who were considered more agreeable (Judge, Livingston, & Hurst, 2012). The last of the Big Five traits is neuroticism, which is the tendency to experience negative emotions. People high on neuroticism tend to experience emotional instability and are characterized as angry, impulsive, and hostile. Watson and Clark (1984) found that people reporting high levels of neuroticism also tend to report feeling anxious and unhappy. In contrast, people who score low in neuroticism tend to be calm and even-tempered.

Figure 11.15 In the Five Factor Model, each person has five traits, each scored on a continuum from high to low. In the center column, notice that the first letter of each trait spells the mnemonic OCEAN.

The Big Five personality factors each represent a range between two extremes. In reality, most of us tend to lie somewhere midway along the continuum of each factor, rather than at polar ends. It’s important to note that the Big Five traits are relatively stable over our lifespan, with some tendency for the traits to increase or decrease slightly. Researchers have found that conscientiousness increases through young adulthood into middle age, as we become better able to manage our personal relationships and careers (Donnellan & Lucas, 2008). Agreeableness also increases with age, peaking between 50 to 70 years (Terracciano, McCrae, Brant, & Costa, 2005). Neuroticism and extroversion tend to decline slightly with age (Donnellan & Lucas; Terracciano et al.). Additionally, The Big Five traits have been shown to exist across ethnicities, cultures, and ages, and may have substantial biological and genetic components (Jang, Livesley, & Vernon, 1996; Jang et al., 2006; McCrae & Costa, 1997; Schmitt et al., 2007).

LINK TO LEARNINGTo find out about your personality and where you fall on the Big Five traits, follow thislink (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/big5) to take the Big Five personality test.

Personality Assessment

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Discuss the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory

- Recognize and describe common projective tests used in personality assessment

Roberto, Mikhail, and Nat are college friends and all want to be police officers. Roberto is quiet and shy, lacks self-confidence, and usually follows others. He is a kind person, but lacks motivation. Mikhail is loud and boisterous, a leader. He works hard, but is impulsive and drinks too much on the weekends. Nat is thoughtful and well liked. He is trustworthy, but sometimes he has difficulty making quick decisions. Of these three men, who would make the best police officer? What qualities and personality factors make someone a good police officer? What makes someone a bad or dangerous police officer?

A police officer’s job is very high in stress, and law enforcement agencies want to make sure they hire the right people. Personality testing is often used for this purpose—to screen applicants for employment and job training. Personality tests are also used in criminal cases and custody battles, and to assess psychological disorders. This section explores the best known among the many different types of personality tests.

SELF-REPORT INVENTORIES

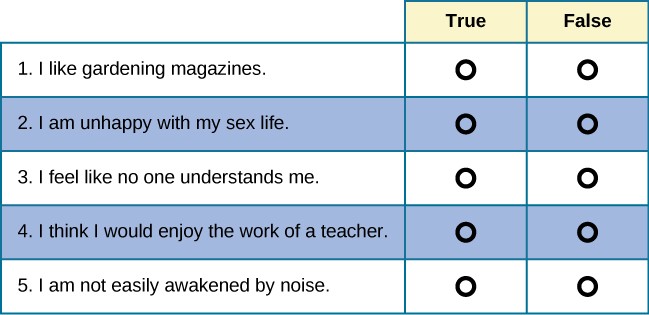

Self-report inventories are a kind of objective test used to assess personality. They typically use multiple- choice items or numbered scales, which represent a range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). They often are called Likert scales after their developer, Rensis Likert (1932) ( Figure 11.17).

Figure 11.17 If you’ve ever taken a survey, you are probably familiar with Likert-type scale questions. Most personality inventories employ these types of response scales.

One of the most widely used personality inventories is the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI), first published in 1943, with 504 true/false questions, and updated to the MMPI-2 in 1989, with 567 questions. The original MMPI was based on a small, limited sample, composed mostly of Minnesota farmers and psychiatric patients; the revised inventory was based on a more representative, national sample to allow for better standardization. The MMPI-2 takes 1–2 hours to complete. Responses are scored to produce a clinical profile composed of 10 scales: hypochondriasis, depression, hysteria, psychopathic deviance (social deviance), masculinity versus femininity, paranoia, psychasthenia (obsessive/compulsive qualities), schizophrenia, hypomania, and social introversion. There is also a scale to ascertain risk factors for alcohol abuse. In 2008, the test was again revised, using more advanced methods, to the MMPI-2-RF. This version takes about one-half the time to complete and has only 338 questions (Figure 11.18). Despite the new test’s advantages, the MMPI-2 is more established and is still more widely used. Typically, the tests are administered by computer. Although the MMPI was originally developed to assist in the clinical diagnosis of psychological disorders, it is now also used for occupational screening, such as in law enforcement, and in college, career, and marital counseling (Ben-Porath & Tellegen, 2008).

Figure 11.18 These true/false questions resemble the kinds of questions you would find on the MMPI.

In addition to clinical scales, the tests also have validity and reliability scales. (Recall the concepts of reliability and validity from your study of psychological research.) One of the validity scales, the Lie Scale (or “L” Scale), consists of 15 items and is used to ascertain whether the respondent is “faking good” (underreporting psychological problems to appear healthier). For example, if someone responds “yes” to a number of unrealistically positive items such as “I have never told a lie,” they may be trying to “fake

good” or appear better than they actually are.

Reliability scales test an instrument’s consistency over time, assuring that if you take the MMPI-2-RF today and then again 5 years later, your two scores will be similar. Beutler, Nussbaum, and Meredith (1988) gave the MMPI to newly recruited police officers and then to the same police officers 2 years later. After 2 years on the job, police officers’ responses indicated an increased vulnerability to alcoholism, somatic symptoms (vague, unexplained physical complaints), and anxiety. When the test was given an additional 2 years later (4 years after starting on the job), the results suggested high risk for alcohol-related difficulties.

PROJECTIVE TESTS

Another method for assessment of personality is projective testing. This kind of test relies on one of the defense mechanisms proposed by Freud—projection—as a way to assess unconscious processes. During this type of testing, a series of ambiguous cards is shown to the person being tested, who then is encouraged to project his feelings, impulses, and desires onto the cards—by telling a story, interpreting an image, or completing a sentence. Many projective tests have undergone standardization procedures (for example, Exner, 2002) and can be used to access whether someone has unusual thoughts or a high level of anxiety, or is likely to become volatile. Some examples of projective tests are the Rorschach Inkblot Test, the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT), the Contemporized-Themes Concerning Blacks test, the TEMAS (Tell-Me-A-Story), and the Rotter Incomplete Sentence Blank (RISB).

The Rorschach Inkblot Test was developed in 1921 by a Swiss psychologist named Hermann Rorschach (pronounced “ROAR-shock”). It is a series of symmetrical inkblot cards that are presented to a client by a psychologist. Upon presentation of each card, the psychologist asks the client, “What might this be?” What the test-taker sees reveals unconscious feelings and struggles (Piotrowski, 1987; Weiner, 2003). The Rorschach has been standardized using the Exner system and is effective in measuring depression, psychosis, and anxiety.

A second projective test is the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT), created in the 1930s by Henry Murray, an American psychologist, and a psychoanalyst named Christiana Morgan. A person taking the TAT is shown 8–12 ambiguous pictures and is asked to tell a story about each picture. The stories give insight into their social world, revealing hopes, fears, interests, and goals. The storytelling format helps to lower a person’s resistance divulging unconscious personal details (Cramer, 2004). The TAT has been used in clinical settings to evaluate psychological disorders; more recently, it has been used in counseling settings to help clients gain a better understanding of themselves and achieve personal growth. Standardization of test administration is virtually nonexistent among clinicians, and the test tends to be modest to low on validity and reliability (Aronow, Weiss, & Rezinkoff, 2001; Lilienfeld, Wood, & Garb, 2000). Despite these shortcomings, the TAT has been one of the most widely used projective tests.

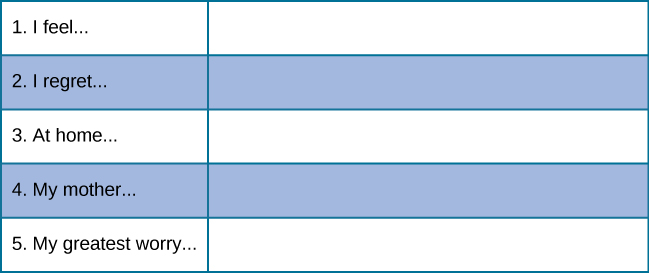

A third projective test is the Rotter Incomplete Sentence Blank (RISB) developed by Julian Rotter in 1950 (recall his theory of locus of control, covered earlier in this chapter). There are three forms of this test for use with different age groups: the school form, the college form, and the adult form. The tests include 40 incomplete sentences that people are asked to complete as quickly as possible (Figure 11.19). The average time for completing the test is approximately 20 minutes, as responses are only 1–2 words in length. This test is similar to a word association test, and like other types of projective tests, it is presumed that responses will reveal desires, fears, and struggles. The RISB is used in screening college students for adjustment problems and in career counseling (Holaday, Smith, & Sherry, 2010; Rotter & Rafferty 1950).

Figure 11.19 These incomplete sentences resemble the types of questions on the RISB. How would you complete these sentences?

For many decades, these traditional projective tests have been used in cross-cultural personality assessments. However, it was found that test bias limited their usefulness (Hoy-Watkins & Jenkins-Moore, 2008). It is difficult to assess the personalities and lifestyles of members of widely divergent ethnic/ cultural groups using personality instruments based on data from a single culture or race (Hoy-Watkins & Jenkins-Moore, 2008). For example, when the TAT was used with African-American test takers, the result was often shorter story length and low levels of cultural identification (Duzant, 2005). Therefore, it was vital to develop other personality assessments that explored factors such as race, language, and level of acculturation (Hoy-Watkins & Jenkins-Moore, 2008). To address this need, Robert Williams developed the first culturally specific projective test designed to reflect the everyday life experiences of African Americans (Hoy-Watkins & Jenkins-Moore, 2008). The updated version of the instrument is the Contemporized-Themes Concerning Blacks Test (C-TCB) (Williams, 1972). The C-TCB contains 20 color images that show scenes of African-American lifestyles. When the C-TCB was compared with the TAT for African Americans, it was found that use of the C-TCB led to increased story length, higher degrees of positive feelings, and stronger identification with the C-TCB (Hoy, 1997; Hoy-Watkins & Jenkins-Moore, 2008).

The TEMAS Multicultural Thematic Apperception Test is another tool designed to be culturally relevant to minority groups, especially Hispanic youths. TEMAS—standing for “Tell Me a Story” but also a play on the Spanish word temas (themes)—uses images and storytelling cues that relate to minority culture (Constantino, 1982).

Key Terms

anal stage psychosexual stage in which children experience pleasure in their bowel and bladder movements

analytical psychology Jung’s theory focusing on the balance of opposing forces within one’s personality

and the significance of the collective unconscious

archetype pattern that exists in our collective unconscious across cultures and societies

collective unconscious

generation to the next

common psychological tendencies that have been passed down from one

congruence state of being in which our thoughts about our real and ideal selves are very similar

conscious mental activity (thoughts, feelings, and memories) that we can access at any time

Contemporized-Themes Concerning Blacks Test (C-TCB) projective test designed to be culturally

relevant to African Americans, using images that relate to African-American culture

culture all of the beliefs, customs, art, and traditions of a particular society

defense mechanism unconscious protective behaviors designed to reduce ego anxiety

displacement ego defense mechanism in which a person transfers inappropriate urges or behaviors

toward a more acceptable or less threatening target

ego aspect of personality that represents the self, or the part of one’s personality that is visible to others

Five Factor Model theory that personality is composed of five factors or traits, including openness,

conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism

genital stage psychosexual stage in which the focus is on mature sexual interests

heritability proportion of difference among people that is attributed to genetics

id aspect of personality that consists of our most primitive drives or urges, including impulses for hunger, thirst, and sex

ideal self person we would like to be

incongruence state of being in which there is a great discrepancy between our real and ideal selves

individual psychology school of psychology proposed by Adler that focuses on our drive to

compensate for feelings of inferiority

inferiority complex refers to a person’s feelings that they lack worth and don’t measure up to others’ or to society’s standards

latency period psychosexual stage in which sexual feelings are dormant

locus of control beliefs about the power we have over our lives; an external locus of control is the belief that our outcomes are outside of our control; an internal locus of control is the belief that we control our own outcomes

Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) personality test composed of a series of true/ false questions in order to establish a clinical profile of an individual

neurosis oral stage

tendency to experience negative emotions

psychosexual stage in which an infant’s pleasure is focused on the mouth

personality long-standing traits and patterns that propel individuals to consistently think, feel, and behave in specific ways

phallic stage psychosexual stage in which the focus is on the genitals

projection ego defense mechanism in which a person confronted with anxiety disguises their

unacceptable urges or behaviors by attributing them to other people

Projective test personality assessment in which a person responds to ambiguous stimuli, revealing

hidden feelings, impulses, and desires

psychosexual stages of development

stages of child development in which a child’s pleasure-seeking

urges are focused on specific areas of the body called erogenous zones

rationalization

justify behavior

ego defense mechanism in which a person confronted with anxiety makes excuses to

reaction formation ego defense mechanism in which a person confronted with anxiety swaps

unacceptable urges or behaviors for their opposites

real self person who we actually are

reciprocal determinism belief that one’s environment can determine behavior, but at the same time, people can influence the environment with both their thoughts and behaviors

regression ego defense mechanism in which a person confronted with anxiety returns to a more

immature behavioral state

repression

unconscious

ego defense mechanism in which anxiety-related thoughts and memories are kept in the

Rorschach Inkblot Test projective test that employs a series of symmetrical inkblot cards that are presented to a client by a psychologist in an effort to reveal the person’s unconscious desires, fears, and struggles

Rotter Incomplete Sentence Blank (RISB) projective test that is similar to a word association test in

which a person completes sentences in order to reveal their unconscious desires, fears, and struggles

selective migration concept that people choose to move to places that are compatible with their personalities and needs

self-concept our thoughts and feelings about ourselves

self-efficacy someone’s level of confidence in their own abilities

social-cognitive theory Bandura’s theory of personality that emphasizes both cognition and learning as

sources of individual differences in personality

sublimation

activities

ego defense mechanism in which unacceptable urges are channeled into more appropriate

superego aspect of the personality that serves as one’s moral compass, or conscience

TEMAS Multicultural Thematic Apperception Test projective test designed to be culturally relevant to

minority groups, especially Hispanic youths, using images and storytelling that relate to minority culture

temperament

very young

how a person reacts to the world, including their activity level, starting when they are

Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) projective test in which people are presented with ambiguous

images, and they then make up stories to go with the images in an effort to uncover their unconscious desires, fears, and struggles

traits characteristic ways of behaving

unconscious mental activity of which we are unaware and unable to access

Summary

What Is Personality?