Chapter 5: Sensation and Perception

Introduction

Imagine standing on a city street corner. You might be struck by movement everywhere as cars and people go about their business, by the sound of a street musician’s melody or a horn honking in the distance, by the smell of exhaust fumes or of food being sold by a nearby vendor, and by the sensation of hard pavement under your feet.

We rely on our sensory systems to provide important information about our surroundings. We use this information to successfully navigate and interact with our environment so that we can find nourishment, seek shelter, maintain social relationships, and avoid potentially dangerous situations.

This chapter will provide an overview of how sensory information is received and processed by the nervous system and how that affects our conscious experience of the world. We begin by learning the distinction between sensation and perception. Then we consider the physical properties of light and sound stimuli, along with an overview of the basic structure and function of the major sensory systems. The chapter will close with a discussion of a historically important theory of perception called Gestalt.

Sensations Versus Perception

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Distinguish between sensation and perception

- Describe the concepts of absolute threshold and difference threshold

- Discuss the roles attention, motivation, and sensory adaptation play in perception

SENSATION

What does it mean to sense something? Sensory receptors are specialized neurons that respond to specific types of stimuli. When sensory information is detected by a sensory receptor, sensation has occurred. For example, light that enters the eye causes chemical changes in cells that line the back of the eye. These cells relay messages, in the form of action potentials (as you learned when studying biopsychology), to the central nervous system. The conversion from sensory stimulus energy to action potential is known as transduction. Besides our typical five session, our sensory system also provides information about balance (the vestibular sense), body position and movement (proprioception and kinesthesia), pain (nociception), and temperature (thermoception).

The sensitivity of a given sensory system to the relevant stimuli can be expressed as an absolute threshold. Absolute threshold refers to the minimum amount of stimulus energy that must be present for the stimulus to be detected 50% of the time. Another way to think about this is by asking how dim can a light be or how soft can a sound be and still be detected half of the time. The sensitivity of our sensory receptors can be quite amazing. It has been estimated that on a clear night, the most sensitive sensory cells in the back of the eye can detect a candle flame 30 miles away (Okawa & Sampath, 2007). Under quiet conditions, the hair cells (the receptor cells of the inner ear) can detect the tick of a clock 20 feet away (Galanter, 1962).

It is also possible for us to get messages that are presented below the threshold for conscious awareness—these are called subliminal messages. A stimulus reaches a physiological threshold when it is strong enough to excite sensory receptors and send nerve impulses to the brain: This is an absolute threshold. A message below that threshold is said to be subliminal: We receive it, but we are not consciously aware of it. Over the years there has been a great deal of speculation about the use of subliminal messages in advertising, rock music, and self-help audio programs. Research evidence shows that in laboratory settings, people can process and respond to information outside of awareness.

Absolute thresholds are generally measured under incredibly controlled conditions in situations that are optimal for sensitivity. Sometimes, we are more interested in how much difference in stimuli is required to detect a difference between them. This is known as the just noticeable difference (jnd) or difference threshold. Unlike the absolute threshold, the difference threshold changes depending on the stimulus intensity.

PERCEPTION

While our sensory receptors are constantly collecting information from the environment, it is ultimately how we interpret that information that affects how we interact with the world. Perception refers to the way sensory information is organized, interpreted, and consciously experienced. Perception involves both bottom-up and top-down processing. Bottom-up processing refers to the fact that perceptions are built from sensory input. On the other hand, how we interpret those sensations is influenced by our available knowledge, our experiences, and our thoughts. This is called top-down processing. One way to think of this concept is that sensation is a physical process, whereas perception is psychological. For example, upon walking into a kitchen and smelling the scent of baking cinnamon rolls, the sensation is the scent receptors detecting the odor of cinnamon, but the perception may be “Mmm, this smells like the bread Grandma used to bake when the family gathered for holidays.”

Although our perceptions are built from sensations, not all sensations result in perception. In fact, we often don’t perceive stimuli that remain relatively constant over prolonged periods of time. This is known as sensory adaptation. Imagine entering a classroom with an old analog clock. Upon first entering the room, you can hear the ticking of the clock; as you begin to engage in conversation with classmates or listen to your professor greet the class, you are no longer aware of the ticking. The clock is still ticking, and that information is still affecting sensory receptors of the auditory system. The fact that you no longer perceive the sound demonstrates sensory adaptation and shows that while closely associated, sensation and perception are different.

There is another factor that affects sensation and perception: attention. Attention plays a significant role in determining what is sensed versus what is perceived. Imagine you are at a party full of music, chatter, and laughter. You get involved in an interesting conversation with a friend, and you tune out all the background noise. If someone interrupted you to ask what song had just finished playing, you would probably be unable to answer that question. Failure to notice something that is completely visible because of a lack of attention is called inattentional blindness.

Motivation can also affect perception. Have you ever been expecting a really important phone call and, while taking a shower, you think you hear the phone ringing, only to discover that it is not? If so, then you have experienced how motivation to detect a meaningful stimulus can shift our ability to discriminate between a true sensory stimulus and background noise. The ability to identify a stimulus when it is embedded in a distracting background is called signal detection theory. This might also explain why a mother is awakened by a quiet murmur from her baby but not by other sounds that occur while she is asleep. Signal detection theory has practical applications, such as increasing air traffic controller accuracy. Controllers need to be able to detect planes among many signals (blips) that appear on the radar screen and follow those planes as they move through the sky. In fact, the original work of the researcher who developed signal detection theory was focused on improving the sensitivity of air traffic controllers to plane blips (Swets, 1964).

Our perceptions can also be affected by our beliefs, values, prejudices, expectations, and life experiences. As you will see later in this chapter, individuals who are deprived of the experience of binocular vision during critical periods of development have trouble perceiving depth (Fawcett, Wang, & Birch, 2005). Children described as thrill seekers are more likely to show taste preferences for intense sour flavors (Liem, Westerbeek, Wolterink, Kok, & de Graaf, 2004), which suggests that basic aspects of personality might affect perception. Furthermore, individuals who hold positive attitudes toward reduced-fat foods are more likely to rate foods labeled as reduced fat as tasting better than people who have less positive attitudes about these products (Aaron, Mela, & Evans, 1994).

Vision

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the basic anatomy of the visual system

- Discuss how rods and cones contribute to different aspects of vision

- Describe how monocular and binocular cues are used in the perception of depth

The visual system constructs a mental representation of the world around us (Figure 5.9). This contributes to our ability to successfully navigate through physical space and interact with important individuals and objects in our environments. This section will provide an overview of the basic anatomy and function of the visual system. In addition, we will explore our ability to perceive color and depth.

Figure 5.9 Our eyes take in sensory information that helps us understand the world around us.

ANATOMY OF THE VISUAL SYSTEM

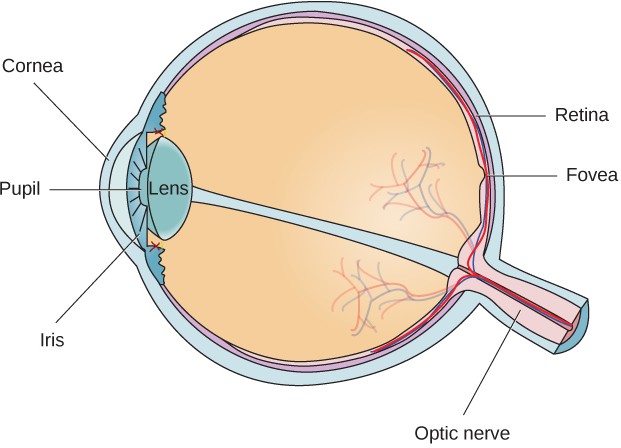

The eye is the major sensory organ involved in vision (Figure 5.10). Light waves are transmitted across the cornea and enter the eye through the pupil. The cornea is the transparent covering over the eye. It serves as a barrier between the inner eye and the outside world, and it is involved in focusing light waves that enter the eye. The pupil is the small opening in the eye through which light passes, and the size of the pupil can change as a function of light levels as well as emotional arousal. When light levels are low, the pupil will become dilated, or expanded, to allow more light to enter the eye. When light levels are high, the pupil will constrict, or become smaller, to reduce the amount of light that enters the eye. The pupil’s size is controlled by muscles that are connected to the iris, which is the colored portion of the eye.

Figure 5.10 The anatomy of the eye is illustrated in this diagram.

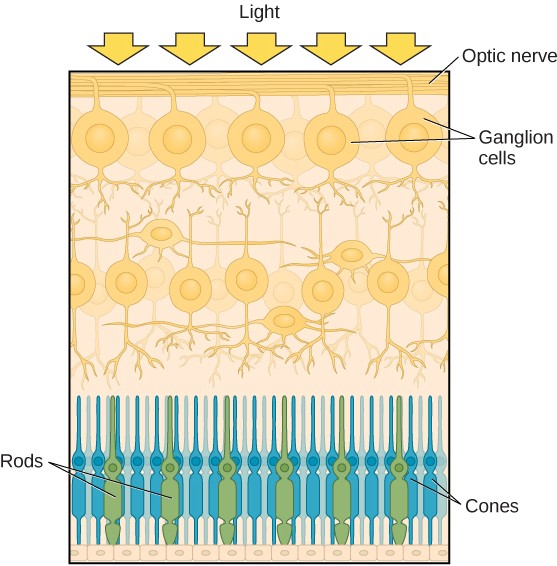

After passing through the pupil, light crosses the lens, a curved, transparent structure that serves to provide additional focus. The lens is attached to muscles that can change its shape to aid in focusing light that is reflected from near or far objects. In a normal-sighted individual, the lens will focus images perfectly on a small indentation in the back of the eye known as the fovea, which is part of the retina, the light-sensitive lining of the eye. The fovea contains densely packed specialized photoreceptor cells (Figure 5.11). These photoreceptor cells, known as cones, are light-detecting cells. The cones are specialized types of photoreceptors that work best in bright light conditions. Cones are very sensitive to acute detail and provide tremendous spatial resolution. They also are directly involved in our ability to perceive color.

While cones are concentrated in the fovea, where images tend to be focused, rods, another type of photoreceptor, are located throughout the remainder of the retina. Rods are specialized photoreceptors that work well in low light conditions, and while they lack the spatial resolution and color function of the cones, they are involved in our vision in dimly lit environments as well as in our perception of movement on the periphery of our visual field.

Figure 5.11 The two types of photoreceptors are shown in this image. Rods are colored green and cones are blue.

We have all experienced the different sensitivities of rods and cones when making the transition from a brightly lit environment to a dimly lit environment. Imagine going to see a blockbuster movie on a clear summer day. As you walk from the brightly lit lobby into the dark theater, you notice that you immediately have difficulty seeing much of anything. After a few minutes, you begin to adjust to the darkness and can see the interior of the theater. In the bright environment, your vision was dominated primarily by cone activity. As you move to the dark environment, rod activity dominates, but there is a delay in transitioning between the phases. If your rods do not transform light into nerve impulses as easily and efficiently as they should, you will have difficulty seeing in dim light, a condition known as night blindness.

Rods and cones are connected (via several interneurons) to retinal ganglion cells. Axons from the retinal ganglion cells converge and exit through the back of the eye to form the optic nerve. The optic nerve carries visual information from the retina to the brain. There is a point in the visual field called the blind spot: Even when light from a small object is focused on the blind spot, we do not see it. We are not consciously aware of our blind spots for two reasons: First, each eye gets a slightly different view of the visual field; therefore, the blind spots do not overlap. Second, our visual system fills in the blind spot so that although we cannot respond to visual information that occurs in that portion of the visual field, we are also not aware that information is missing.

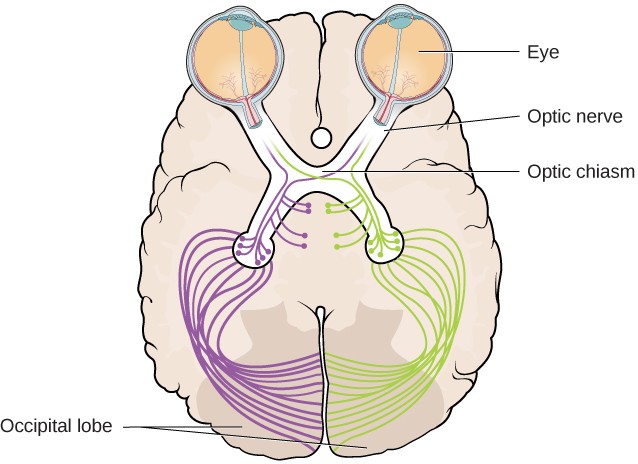

The optic nerve from each eye merges just below the brain at a point called the optic chiasm. As Figure5.12 shows, the optic chiasm is an X-shaped structure that sits just below the cerebral cortex at the front of the brain. At the point of the optic chiasm, information from the right visual field (which comes from both eyes) is sent to the left side of the brain, and information from the left visual field is sent to the right side of the brain.

Figure 5.12 This illustration shows the optic chiasm at the front of the brain and the pathways to the occipital lobe at the back of the brain, where visual sensations are processed into meaningful perceptions.

Once inside the brain, visual information is sent via a number of structures to the occipital lobe at the back of the brain for processing. Visual information might be processed in parallel pathways which can generally be described as the “what pathway” and the “where/how” pathway. The “what pathway” is involved in object recognition and identification, while the “where/how pathway” is involved with location in space and how one might interact with a particular visual stimulus (Milner & Goodale, 2008; Ungerleider & Haxby, 1994). For example, when you see a ball rolling down the street, the “what pathway” identifies what the object is, and the “where/how pathway” identifies its location or movement in space.

COLOR AND DEPTH PERCEPTION

Color Vision

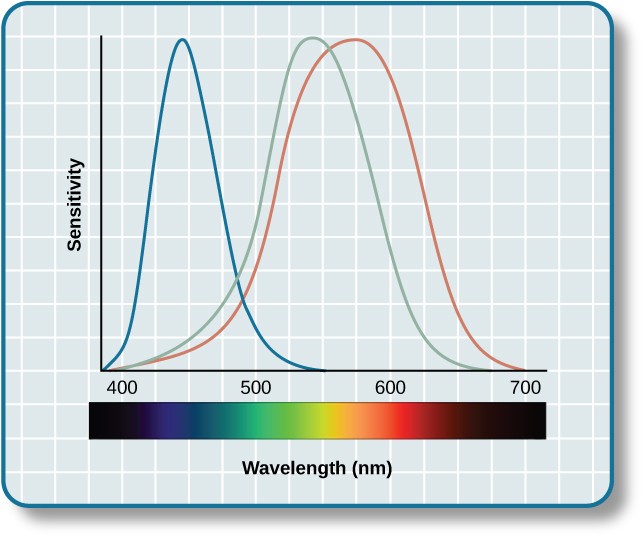

Normal-sighted individuals have three different types of cones that mediate color vision. Each of these cone types is maximally sensitive to a slightly different wavelength of light. According to the trichromatic theory of color vision, shown in Figure 5.13, all colors in the spectrum can be produced by combining red, green, and blue. The three types of cones are each receptive to one of the colors.

Figure 5.13 This figure illustrates the different sensitivities for the three cone types found in a normal-sighted individual. (credit: modification of work by Vanessa Ezekowitz)

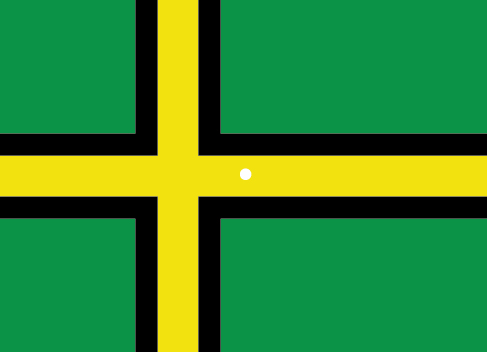

The trichromatic theory of color vision is not the only theory—another major theory of color vision is known as the opponent-process theory. According to this theory, color is coded in opponent pairs: black- white, yellow-blue, and green-red. The basic idea is that some cells of the visual system are excited by one of the opponent colors and inhibited by the other. So, a cell that was excited by wavelengths associated with green would be inhibited by wavelengths associated with red, and vice versa. One of the implications of opponent processing is that we do not experience greenish-reds or yellowish-blues as colors. Another implication is that this leads to the experience of negative afterimages. An afterimage describes the continuation of a visual sensation after removal of the stimulus. For example, when you stare briefly at the sun and then look away from it, you may still perceive a spot of light although the stimulus (the sun) has been removed. When color is involved in the stimulus, the color pairings identified in the opponent-process theory lead to a negative afterimage. You can test this concept using the flag in Figure 5.14.

Figure 5.14 Stare at the white dot for 30–60 seconds and then move your eyes to a blank piece of white paper. What do you see? This is known as a negative afterimage, and it provides empirical support for the opponent-process theory of color vision.

Depth Perception

Our ability to perceive spatial relationships in three-dimensional (3-D) space is known as depth perception. With depth perception, we can describe things as being in front, behind, above, below, or to the side of other things.

Our world is three-dimensional, so it makes sense that our mental representation of the world has three- dimensional properties. We use a variety of cues in a visual scene to establish our sense of depth. Some of these are binocular cues, which means that they rely on the use of both eyes. One example of a binocular depth cue is binocular disparity, the slightly different view of the world that each of our eyes receives. To experience this slightly different view, do this simple exercise: extend your arm fully and extend one of your fingers and focus on that finger. Now, close your left eye without moving your head, then open your left eye and close your right eye without moving your head. You will notice that your finger seems to shift as you alternate between the two eyes because of the slightly different view each eye has of your finger.

Although we rely on binocular cues to experience depth in our 3-D world, we can also perceive depth in 2-D arrays. Think about all the paintings and photographs you have seen. Generally, you pick up on depth in these images even though the visual stimulus is 2-D. When we do this, we are relying on a number of monocular cues, or cues that require only one eye. If you think you can’t see depth with one eye, note that you don’t bump into things when using only one eye while walking—and, in fact, we have more monocular cues than binocular cues.

An example of a monocular cue would be what is known as linear perspective. Linear perspective refers to the fact that we perceive depth when we see two parallel lines that seem to converge in an image (Figure 5.15). Some other monocular depth cues are interposition, the partial overlap of objects, and the relative size and closeness of images to the horizon.

Figure 5.15 We perceive depth in a two-dimensional figure like this one through the use of monocular cues like linear perspective, like the parallel lines converging as the road narrows in the distance. (credit: Marc Dalmulder)

Audition

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the basic anatomy and function of the auditory system

- Explain how we encode and perceive pitch

- Discuss how we localize sound

Our auditory system converts pressure waves into meaningful sounds. This translates into our ability to hear the sounds of nature, to appreciate the beauty of music, and to communicate with one another through spoken language. This section will provide an overview of the basic anatomy and function of the auditory system. It will include a discussion of how the sensory stimulus is translated into neural impulses, where in the brain that information is processed, how we perceive pitch, and how we know where sound is coming from.

ANATOMY OF THE AUDITORY SYSTEM

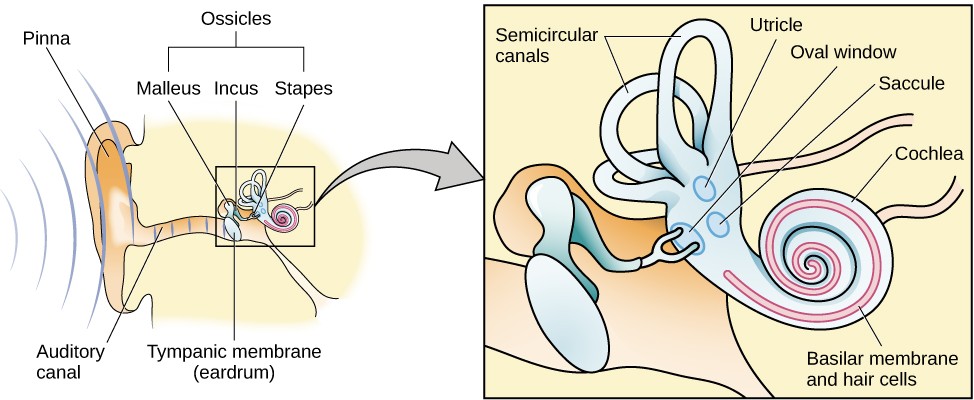

The ear can be separated into multiple sections. The outer ear includes the pinna, which is the visible part of the ear that protrudes from our heads, the auditory canal, and the tympanic membrane, or eardrum. The middle ear contains three tiny bones known as the ossicles, which are named the malleus (or hammer), incus (or anvil), and the stapes (or stirrup). The inner ear contains the semi-circular canals, which are involved in balance and movement (the vestibular sense), and the cochlea. The cochlea is a fluid- filled, snail-shaped structure that contains the sensory receptor cells (hair cells) of the auditory system (Figure 5.16).

Figure 5.16 The ear is divided into outer (pinna and tympanic membrane), middle (the three ossicles: malleus, incus, and stapes), and inner (cochlea and basilar membrane) divisions.

Sound waves travel along the auditory canal and strike the tympanic membrane, causing it to vibrate. This vibration results in movement of the three ossicles. As the ossicles move, the stapes presses into a thin membrane of the cochlea known as the oval window. As the stapes presses into the oval window, the fluid inside the cochlea begins to move, which in turn stimulates hair cells, which are auditory receptor cells of the inner ear embedded in the basilar membrane. The basilar membrane is a thin strip of tissue within the cochlea.

The activation of hair cells is a mechanical process: the stimulation of the hair cell ultimately leads to activation of the cell. As hair cells become activated, they generate neural impulses that travel along the auditory nerve to the brain. Auditory information is shuttled to the inferior colliculus, the medial geniculate nucleus of the thalamus, and finally to the auditory cortex in the temporal lobe of the brain for processing. Like the visual system, there is also evidence suggesting that information about auditory recognition and localization is processed in parallel streams (Rauschecker & Tian, 2000; Renier et al., 2009).

PITCH PERCEPTION

Different frequencies of sound waves are associated with differences in our perception of the pitch of those sounds. Low-frequency sounds are lower pitched, and high-frequency sounds are higher pitched. How does the auditory system differentiate among various pitches?

Several theories have been proposed to account for pitch perception. We’ll discuss two of them here: temporal theory and place theory. The temporal theory of pitch perception asserts that frequency is coded by the activity level of a sensory neuron. This would mean that a given hair cell would fire action potentials related to the frequency of the sound wave. While this is a very intuitive explanation, we detect such a broad range of frequencies (20–20,000 Hz) that the frequency of action potentials fired by hair cells cannot account for the entire range. Because of properties related to sodium channels on the neuronal membrane that are involved in action potentials, there is a point at which a cell cannot fire any faster (Shamma, 2001).

The place theory of pitch perception suggests that different portions of the basilar membrane are sensitive to sounds of different frequencies. More specifically, the base of the basilar membrane responds best to high frequencies and the tip of the basilar membrane responds best to low frequencies. Therefore, hair cells that are in the base portion would be labeled as high-pitch receptors, while those in the tip of basilar membrane would be labeled as low-pitch receptors (Shamma, 2001).

SOUND LOCALIZATION

The ability to locate sound in our environments is an important part of hearing. Localizing sound could be considered similar to the way that we perceive depth in our visual fields. Like the monocular and binocular cues that provided information about depth, the auditory system uses both monaural (one-eared) and binaural (two-eared) cues to localize sound.

Each pinna interacts with incoming sound waves differently, depending on the sound’s source relative to our bodies. This interaction provides a monaural cue that is helpful in locating sounds that occur above or below and in front or behind us. The sound waves received by your two ears from sounds that come from directly above, below, in front, or behind you would be identical; therefore, monaural cues are essential (Grothe, Pecka, & McAlpine, 2010).

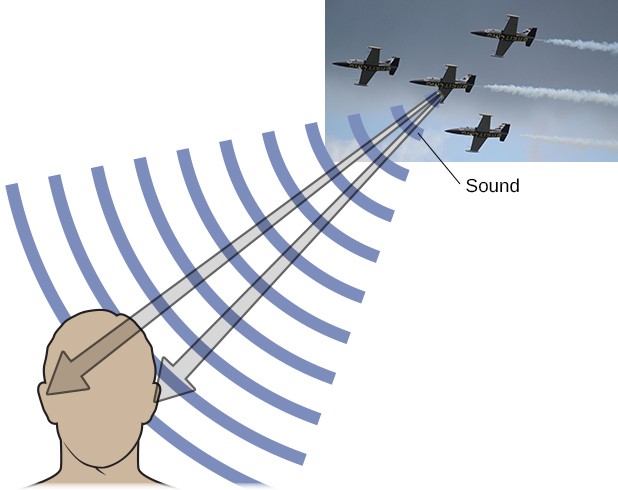

Binaural cues, on the other hand, provide information on the location of a sound along a horizontal axis by relying on differences in patterns of vibration of the eardrum between our two ears. If a sound comes from an off-center location, it creates two types of binaural cues: interaural level differences and interaural timing differences. Interaural level difference refers to the fact that a sound coming from the right side of your body is more intense at your right ear than at your left ear because of the attenuation of the sound wave as it passes through your head. Interaural timing difference refers to the small difference in the time at which a given sound wave arrives at each ear (Figure 5.17). Certain brain areas monitor these differences to construct where along a horizontal axis a sound originates (Grothe et al., 2010).

Figure 5.17 Localizing sound involves the use of both monaural and binaural cues. (credit “plane”: modification of work by Max Pfandl)

HEARING LOSS

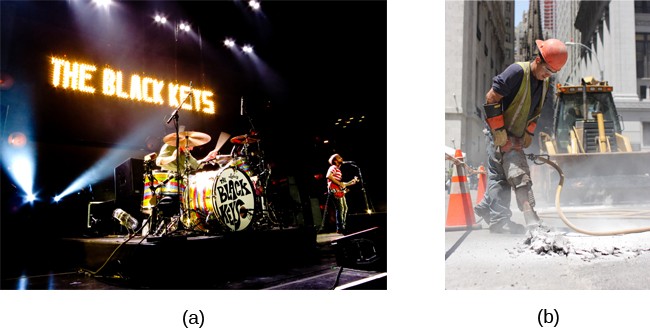

Deafness is the partial or complete inability to hear. Some people are born deaf, which is known as congenital deafness. Many others begin to suffer from conductive hearing loss because of age, genetic predisposition, or environmental effects, including exposure to extreme noise (noise-induced hearing loss, as shown in Figure 5.18), certain illnesses (such as measles or mumps), or damage due to toxins (such as those found in certain solvents and metals).

Figure 5.18 Environmental factors that can lead to conductive hearing loss include regular exposure to loud music or construction equipment. (a) Rock musicians and (b) construction workers are at risk for this type of hearing loss. (credit a: modification of work by Kenny Sun; credit b: modification of work by Nick Allen)

Given the mechanical nature by which the sound wave stimulus is transmitted from the eardrum through the ossicles to the oval window of the cochlea, some degree of hearing loss is inevitable. With conductive hearing loss, hearing problems are associated with a failure in the vibration of the eardrum and/or movement of the ossicles. These problems are often dealt with through devices like hearing aids that amplify incoming sound waves to make vibration of the eardrum and movement of the ossicles more likely to occur.

When the hearing problem is associated with a failure to transmit neural signals from the cochlea to the brain, it is called sensorineural hearing loss. This kind of loss cannot be treated with hearing aids, but some individuals might be candidates for a cochlear implant as a treatment option. Cochlear implants are electronic devices that consist of a microphone, a speech processor, and an electrode array. The device receives incoming sound information and directly stimulates the auditory nerve to transmit information to the brain.

The Other Senses

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the basic functions of the chemical senses

- Explain the basic functions of the somatosensory, nociceptive, and thermoceptive sensory systems

- Describe the basic functions of the vestibular, proprioceptive, and kinesthetic sensory systems

Vision and hearing have received an incredible amount of attention from researchers over the years. While there is still much to be learned about how these sensory systems work, we have a much better understanding of them than of our other sensory modalities. In this section, we will explore our chemical senses (taste and smell) and our body senses (touch, temperature, pain, balance, and body position).

THE CHEMICAL SENSES

Taste (gustation) and smell (olfaction) are called chemical senses because both have sensory receptors that respond to molecules in the food we eat or in the air we breathe. There is a pronounced interaction between our chemical senses. For example, when we describe the flavor of a given food, we are really referring to both gustatory and olfactory properties of the food working in combination.

Taste (Gustation)

You have learned since elementary school that there are four basic groupings of taste: sweet, salty, sour, and bitter. Research demonstrates, however, that we have at least six taste groupings. Umami is our fifth taste. Umami is actually a Japanese word that roughly translates to yummy, and it is associated with a taste for monosodium glutamate (Kinnamon & Vandenbeuch, 2009). There is also a growing body of experimental evidence suggesting that we possess a taste for the fatty content of a given food (Mizushige, Inoue, & Fushiki, 2007).

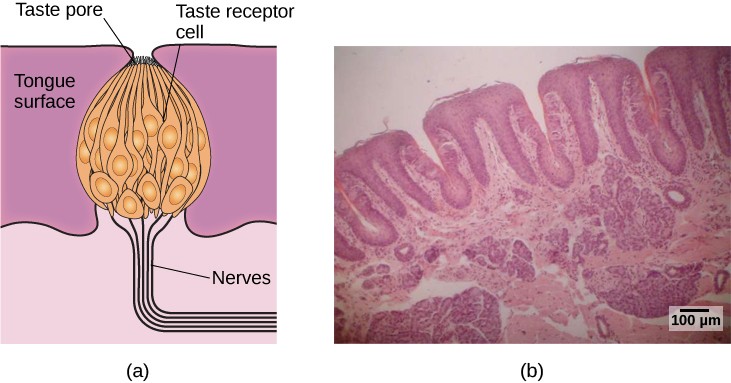

Molecules from the food and beverages we consume dissolve in our saliva and interact with taste receptors on our tongue and in our mouth and throat. Taste buds are formed by groupings of taste receptor cells with hair-like extensions that protrude into the central pore of the taste bud (Figure 5.19). Taste buds have a life cycle of ten days to two weeks, so even destroying some by burning your tongue won’t have any long-term effect; they just grow right back. Taste molecules bind to receptors on this extension and cause chemical changes within the sensory cell that result in neural impulses being transmitted to the brain via different nerves, depending on where the receptor is located. Taste information is transmitted to the medulla, thalamus, and limbic system, and to the gustatory cortex, which is tucked underneath the overlap between the frontal and temporal lobes (Maffei, Haley, & Fontanini, 2012; Roper, 2013).

Figure 5.19 (a) Taste buds are composed of a number of individual taste receptors cells that transmit information to nerves. (b) This micrograph shows a close-up view of the tongue’s surface. (credit a: modification of work by Jonas Töle; credit b: scale-bar data from Matt Russell)

Smell (Olfaction)

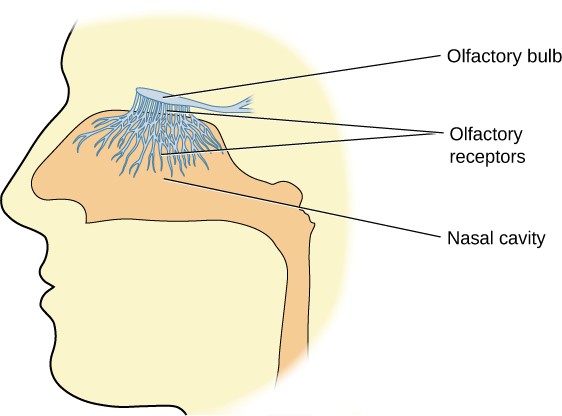

Olfactory receptor cells are located in a mucous membrane at the top of the nose. Small hair-like extensions from these receptors serve as the sites for odor molecules dissolved in the mucus to interact with chemical receptors located on these extensions (Figure 5.20). Once an odor molecule has bound a given receptor, chemical changes within the cell result in signals being sent to the olfactory bulb: a bulb-like structure at the tip of the frontal lobe where the olfactory nerves begin. From the olfactory bulb, information is sent to regions of the limbic system and to the primary olfactory cortex, which is located very near the gustatory cortex (Lodovichi & Belluscio, 2012; Spors et al., 2013).

Figure 5.20 Olfactory receptors are the hair-like parts that extend from the olfactory bulb into the mucous membrane of the nasal cavity.

Many species respond to chemical messages, known as pheromones, sent by another individual (Wysocki & Preti, 2004). Pheromonal communication often involves providing information about the reproductive status of a potential mate. So, for example, when a female rat is ready to mate, she secretes pheromonal signals that draw attention from nearby male rats. Pheromonal activation is actually an important component in eliciting sexual behavior in the male rat (Furlow, 1996, 2012; Purvis & Haynes, 1972; Sachs, 1997). There has also been a good deal of research (and controversy) about pheromones in humans (Comfort, 1971; Russell, 1976; Wolfgang-Kimball, 1992; Weller, 1998).

TOUCH, THERMOCEPTION, AND NOCICEPTION

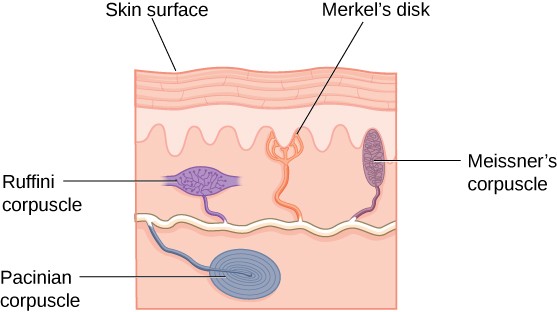

A number of receptors are distributed throughout the skin to respond to various touch-related stimuli (Figure 5.21). These receptors include Meissner’s corpuscles, Pacinian corpuscles, Merkel’s disks, and Ruffini corpuscles. Meissner’s corpuscles respond to pressure and lower frequency vibrations, and Pacinian corpuscles detect transient pressure and higher frequency vibrations. Merkel’s disks respond to light pressure, while Ruffini corpuscles detect stretch (Abraira & Ginty, 2013).

Figure 5.21 There are many types of sensory receptors located in the skin, each attuned to specific touch-related stimuli.

In addition to the receptors located in the skin, there are also a number of free nerve endings that serve sensory functions. These nerve endings respond to a variety of different types of touch-related stimuli and serve as sensory receptors for both thermoception (temperature perception) and nociception (a signal indicating potential harm and maybe pain) (Garland, 2012; Petho & Reeh, 2012; Spray, 1986). Sensory information collected from the receptors and free nerve endings travels up the spinal cord and is transmitted to regions of the medulla, thalamus, and ultimately to somatosensory cortex, which is located in the postcentral gyrus of the parietal lobe.

Pain Perception

Pain is an unpleasant experience that involves both physical and psychological components. Feeling pain is quite adaptive because it makes us aware of an injury, and it motivates us to remove ourselves from the cause of that injury. In addition, pain also makes us less likely to suffer additional injury because we will be gentler with our injured body parts.

Generally speaking, pain can be considered to be neuropathic or inflammatory in nature. Pain that signals some type of tissue damage is known as inflammatory pain. In some situations, pain results from damage to neurons of either the peripheral or central nervous system. As a result, pain signals that are sent to the brain get exaggerated. This type of pain is known as neuropathic pain. Multiple treatment options for pain relief range from relaxation therapy to the use of analgesic medications to deep brain stimulation. The most effective treatment option for a given individual will depend on a number of considerations, including the severity and persistence of the pain and any medical/psychological conditions.

Some individuals are born without the ability to feel pain. This very rare genetic disorder is known as congenital insensitivity to pain (or congenital analgesia). While those with congenital analgesia can detect differences in temperature and pressure, they cannot experience pain. As a result, they often suffer significant injuries.

THE VESTIBULAR SENSE, PROPRIOCEPTION, AND KINESTHESIA

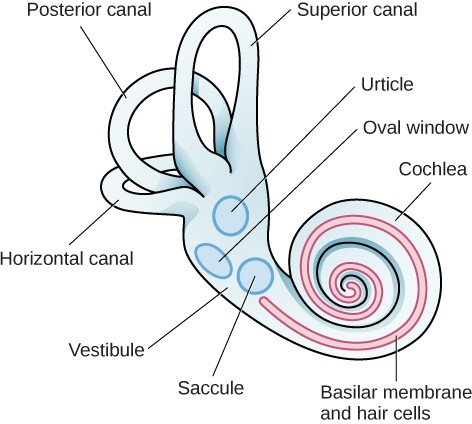

The vestibular sense contributes to our ability to maintain balance and body posture. As Figure 5.22 shows, the major sensory organs (utricle, saccule, and the three semicircular canals) of this system are located next to the cochlea in the inner ear. The vestibular organs are fluid-filled and have hair cells, similar to the ones found in the auditory system, which respond to movement of the head and gravitational forces. When these hair cells are stimulated, they send signals to the brain via the vestibular nerve. Although we may not be consciously aware of our vestibular system’s sensory information under normal circumstances, its importance is apparent when we experience motion sickness and/or dizziness related to infections of the inner ear (Khan & Chang, 2013).

Figure 5.22 The major sensory organs of the vestibular system are located next to the cochlea in the inner ear. These include the utricle, saccule, and the three semicircular canals (posterior, superior, and horizontal).

In addition to maintaining balance, the vestibular system collects information critical for controlling movement and the reflexes that move various parts of our bodies to compensate for changes in body position. Therefore, both proprioception (perception of body position) and kinesthesia (perception of the body’s movement through space) interact with information provided by the vestibular system.

These sensory systems also gather information from receptors that respond to stretch and tension in muscles, joints, skin, and tendons (Lackner & DiZio, 2005; Proske, 2006; Proske & Gandevia, 2012). Proprioceptive and kinesthetic information travels to the brain via the spinal column. Several cortical regions in addition to the cerebellum receive information from and send information to the sensory organs of the proprioceptive and kinesthetic systems.

Gestalt Principles of Perception

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the figure-ground relationship

- Define Gestalt principles of grouping

- Describe how perceptual set is influenced by an individual’s characteristics and mental state

In the early part of the 20th century, Max Wertheimer published a paper demonstrating that individuals perceived motion in rapidly flickering static images—an insight that came to him as he used a child’s toy tachistoscope. Wertheimer, and his assistants Wolfgang Köhler and Kurt Koffka, who later became his partners, believed that perception involved more than simply combining sensory stimuli. This belief led to a new movement within the field of psychology known as Gestalt psychology. The word gestalt literally means form or pattern, but its use reflects the idea that the whole is different from the sum of its parts. In other words, the brain creates a perception that is more than simply the sum of available sensory inputs, and it does so in predictable ways. Gestalt psychologists translated these predictable ways into principles by which we organize sensory information. As a result, Gestalt psychology has been extremely influential in the area of sensation and perception (Rock & Palmer, 1990).

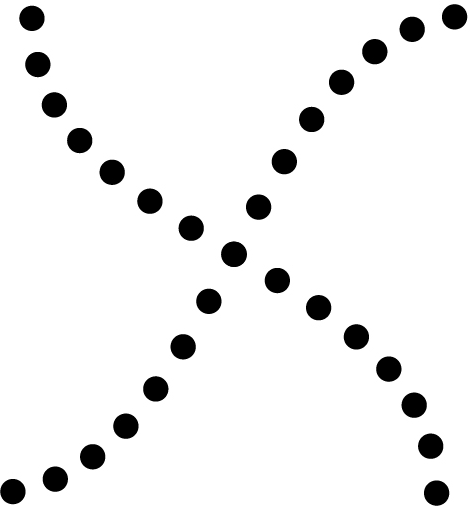

One Gestalt principle is the figure-ground relationship. According to this principle, we tend to segment our visual world into figure and ground. Figure is the object or person that is the focus of the visual field, while the ground is the background. As Figure 5.23 shows, our perception can vary tremendously, depending on what is perceived as figure and what is perceived as ground. Presumably, our ability to interpret sensory information depends on what we label as figure and what we label as ground in any particular case, although this assumption has been called into question (Peterson & Gibson, 1994; Vecera & O’Reilly, 1998).

Figure 5.23 The concept of figure-ground relationship explains why this image can be perceived either as a vase or as a pair of faces.

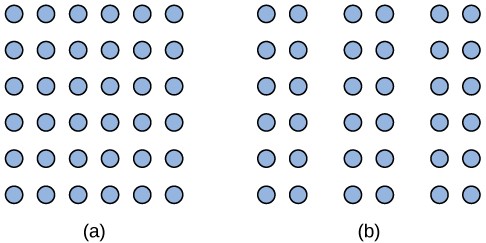

Another Gestalt principle for organizing sensory stimuli into meaningful perception is proximity. This principle asserts that things that are close to one another tend to be grouped together, as Figure 5.24 illustrates.

Figure 5.24 The Gestalt principle of proximity suggests that you see (a) one block of dots on the left side and (b) three columns on the right side.

How we read something provides another illustration of the proximity concept. For example, we read this sentence like this, notl iket hiso rt hat. We group the letters of a given word together because there are no spaces between the letters, and we perceive words because there are spaces between each word. Here are some more examples: Cany oum akes enseo ft hiss entence? What doth es e wor dsmea n?

We might also use the principle of similarity to group things in our visual fields. According to this principle, things that are alike tend to be grouped together (Figure 5.25). For example, when watching a football game, we tend to group individuals based on the colors of their uniforms. When watching an offensive drive, we can get a sense of the two teams simply by grouping along this dimension.

Figure 5.25 When looking at this array of dots, we likely perceive alternating rows of colors. We are grouping these dots according to the principle of similarity.

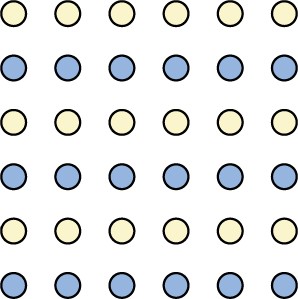

Two additional Gestalt principles are the law of continuity (or good continuation) and closure. The law of continuity suggests that we are more likely to perceive continuous, smooth flowing lines rather than jagged, broken lines (Figure 5.26). The principle of closure states that we organize our perceptions into complete objects rather than as a series of parts (Figure 5.27).

Figure 5.26 Good continuation would suggest that we are more likely to perceive this as two overlapping lines, rather than four lines meeting in the center.

Figure 5.27 Closure suggests that we will perceive a complete circle and rectangle rather than a series of segments.

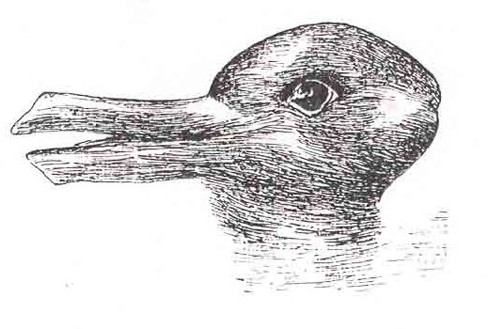

According to Gestalt theorists, pattern perception, or our ability to discriminate among different figures and shapes, occurs by following the principles described above. You probably feel fairly certain that your perception accurately matches the real world, but this is not always the case. Our perceptions are based on perceptual hypotheses: educated guesses that we make while interpreting sensory information. These hypotheses are informed by a number of factors, including our personalities, experiences, and expectations. We use these hypotheses to generate our perceptual set. For instance, research has demonstrated that those who are given verbal priming produce a biased interpretation of complex ambiguous figures (Goolkasian & Woodbury, 2010).

Summary

Sensation versus Perception

Sensation occurs when sensory receptors detect sensory stimuli. Perception involves the organization, interpretation, and conscious experience of those sensations. All sensory systems have both absolute and difference thresholds, which refer to the minimum amount of stimulus energy or the minimum amount of difference in stimulus energy required to be detected about 50% of the time, respectively. Sensory adaptation, selective attention, and signal detection theory can help explain what is perceived and what is not. In addition, our perceptions are affected by a number of factors, including beliefs, values, prejudices, culture, and life experiences.

Vision

Light waves cross the cornea and enter the eye at the pupil. The eye’s lens focuses this light so that the image is focused on a region of the retina known as the fovea. The fovea contains cones that possess high levels of visual acuity and operate best in bright light conditions. Rods are located throughout the retina and operate best under dim light conditions. Visual information leaves the eye via the optic nerve. Information from each visual field is sent to the opposite side of the brain at the optic chiasm. Visual information then moves through a number of brain sites before reaching the occipital lobe, where it is processed.

Two theories explain color perception. The trichromatic theory asserts that three distinct cone groups are tuned to slightly different wavelengths of light, and it is the combination of activity across these cone types that results in our perception of all the colors we see. The opponent-process theory of color vision asserts that color is processed in opponent pairs and accounts for the interesting phenomenon of a negative afterimage. We perceive depth through a combination of monocular and binocular depth cues.

Hearing

Sound waves are funneled into the auditory canal and cause vibrations of the eardrum; these vibrations move the ossicles. As the ossicles move, the stapes presses against the oval window of the cochlea, which

causes fluid inside the cochlea to move. As a result, hair cells embedded in the basilar membrane become enlarged, which sends neural impulses to the brain via the auditory nerve.

Pitch perception and sound localization are important aspects of hearing. Our ability to perceive pitch relies on both the firing rate of the hair cells in the basilar membrane as well as their location within the membrane. In terms of sound localization, both monaural and binaural cues are used to locate where sounds originate in our environment.

Individuals can be born deaf, or they can develop deafness as a result of age, genetic predisposition, and/ or environmental causes. Hearing loss that results from a failure of the vibration of the eardrum or the resultant movement of the ossicles is called conductive hearing loss. Hearing loss that involves a failure of the transmission of auditory nerve impulses to the brain is called sensorineural hearing loss.

The Other Senses

Taste (gustation) and smell (olfaction) are chemical senses that employ receptors on the tongue and in the nose that bind directly with taste and odor molecules in order to transmit information to the brain for processing. Our ability to perceive touch, temperature, and pain is mediated by a number of receptors and free nerve endings that are distributed throughout the skin and various tissues of the body. The vestibular sense helps us maintain a sense of balance through the response of hair cells in the utricle, saccule, and semi-circular canals that respond to changes in head position and gravity. Our proprioceptive and kinesthetic systems provide information about body position and body movement through receptors that detect stretch and tension in the muscles, joints, tendons, and skin of the body.

Gestalt Principles of Perception

Gestalt theorists have been incredibly influential in the areas of sensation and perception. Gestalt principles such as figure-ground relationship, grouping by proximity or similarity, the law of good continuation, and closure are all used to help explain how we organize sensory information. Our perceptions are not infallible, and they can be influenced by bias, prejudice, and other factors.

Review Questions

- refers to the minimum amount of stimulus energy required to be detected 50% of the time.

- absolute threshold

- difference threshold

- just noticeable difference

- transduction

- Decreased sensitivity to an unchanging stimulus is known as .

- transduction

- difference threshold

- sensory adaptation

- inattentional blindness

- involves the conversion of sensory stimulus energy into neural impulses.

- sensory adaptation

- inattentional blindness

- difference threshold

- transduction

occurs when sensory information is organized, interpreted, and consciously experienced.- sensation

- perception

- transduction

- sensory adaptation

- Which of the following correctly matches the pattern in our perception of color as we move from short wavelengths to long wavelengths?

- red to orange to yellow

- yellow to orange to red

- yellow to red to orange

- orange to yellow to red

- The visible spectrum includes light that ranges from about .

a. 400–700 nm

b. 200–900 nm

c. 20–20000 Hz

d. 10–20 dB

- The electromagnetic spectrum includes

.

- radio waves

- x-rays

- infrared light

- all of the above

- The audible range for humans is . a. 380–740 Hz

b. 10–20 dB

c. less than 300 dB

d. 20-20,000 Hz

- The quality of a sound that is affected by frequency, amplitude, and timing of the sound wave is known as .

- pitch

- tone

- electromagnetic

- timbre

- The is a small indentation of the

Hair cells located near the base of the basilar membrane respond best to sounds.- low-frequency

- high-frequency

- low-amplitude

- high-amplitude

- The three ossicles of the middle ear are known as .

- malleus, incus, and stapes

- hammer, anvil, and stirrup

- pinna, cochlea, and utricle

- both a and b

- Hearing aids might be effective for treating

.

- Ménière’s disease

- sensorineural hearing loss

- conductive hearing loss

- interaural time differences

- Cues that require two ears are referred to as

retina that contains cones. cues.

- optic chiasm

- optic nerve

- fovea

- iris

- operate best under bright light conditions.

- cones

- rods

- retinal ganglion cells

- striate cortex

- depth cues require the use of both eyes.

- monocular

- binocular

- linear perspective

- accommodating

- If you were to stare at a green dot for a relatively long period of time and then shift your gaze to a blank white screen, you would see a

negative afterimage.

- blue

- yellow

- black

- red

monocular- monaural

- binocular

- binaural

- Chemical messages often sent between two members of a species to communicate something about reproductive status are called .

- hormones

- pheromones

- Merkel’s disks

- Meissner’s corpuscles

- Which taste is associated with monosodium glutamate?

- sweet

- bitter

- umami

- sour

- serve as sensory receptors for temperature and pain stimuli.

- free nerve endings

- Pacinian corpuscles

- Ruffini corpuscles

- Meissner’s corpuscles

- Which of the following is involved in maintaining balance and body posture?

- auditory nerve

- nociceptors

- olfactory bulb

- vestibular system

- According to the principle of , objects that occur close to one another tend to be grouped together.

- similarity

- good continuation

- proximity

- closure

- Our tendency to perceive things as complete objects rather than as a series of parts is known as the principle of .

- closure

- good continuation

- proximity

- similarity

According to the law of , we are more likely to perceive smoothly flowing lines rather than choppy or jagged lines.- closure

- good continuation

- proximity

- similarity

- The main point of focus in a visual display is known as the .

- closure

- perceptual set

- ground

- figure

Critical Thinking Questions

- Not everything that is sensed is perceived. Do you think there could ever be a case where something could be perceived without being sensed?

- Please generate a novel example of how just noticeable difference can change as a function of stimulus intensity.

- Why do you think other species have such different ranges of sensitivity for both visual and auditory stimuli compared to humans?

- Why do you think humans are especially sensitive to sounds with frequencies that fall in the middle portion of the audible range?

- Compare the two theories of color perception. Are they completely different?

- Color is not a physical property of our environment. What function (if any) do you think color vision serves?

- Given what you’ve read about sound localization, from an evolutionary perspective, how does sound localization facilitate survival?

- How can temporal and place theories both be used to explain our ability to perceive the pitch of sound waves with frequencies up to 4000 Hz?

- Many people experience nausea while traveling in a car, plane, or boat. How might you explain this as a function of sensory interaction?

- If you heard someone say that they would do anything not to feel the pain associated with significant injury, how would you respond given what you’ve just read?

- Do you think women experience pain differently than men? Why do you think this is?

- The central tenet of Gestalt psychology is that the whole is different from the sum of its parts. What does this mean in the context of perception?

- Take a look at the following figure. How might you influence whether people see a duck or a rabbit?

Figure 5.28

Personal Application Questions

- Think about a time when you failed to notice something around you because your attention was focused elsewhere. If someone pointed it out, were you surprised that you hadn’t noticed it right away?

- If you grew up with a family pet, then you have surely noticed that they often seem to hear things that you don’t hear. Now that you’ve read this section, you probably have some insight as to why this may be. How would you explain this to a friend who never had the opportunity to take a class like this?

- Take a look at a few of your photos or personal works of art. Can you find examples of linear perspective as a potential depth cue?

- If you had to choose to lose either your vision or your hearing, which would you choose and why?

- As mentioned earlier, a food’s flavor represents an interaction of both gustatory and olfactory information. Think about the last time you were seriously congested due to a cold or the flu. What changes did you notice in the flavors of the foods that you ate during this time?

- Have you ever listened to a song on the radio and sung along only to find out later that you have been singing the wrong lyrics? Once you found the correct lyrics, did your perception of the song change?