Chapter 2 – Digital Culture and Social Media’s Impact on Public Relations

“The Internet is the first thing that humanity has built that humanity doesn’t understand, the largest experiment in anarchy that we have ever had.” — Eric Schmidt, former executive chairman of Alphabet Inc.

Origin

Until the end of 2017, Eric Schmidt was the executive chairman of Alphabet Inc. Alphabet emerged out of Google to become a large holding company that would manage Google and several related properties including YouTube and Calico (a biotech company). Schmidt has a Ph.D. in computer science from Berkeley. He serves on advisory boards for Khan Academy, an education company with strong ties to YouTube, and The Economist, a global news magazine with both digital and print products. Schmidt’s résumé suggests he is intellectually outstanding and that he cares about technology, education and the mass media. If one of the biggest brains of our time, and the former leader of one of the few corporations with direct influence on the way the internet is shaped, describes the internet as “anarchy,” it’s a good indication that things are in flux in the digital world.

Of course, we should analyze critically any statements coming from someone whose primary purpose it is to maximize profits for their company. At the time he made these statements, Schmidt was running Google. The loyalties of executive-level leaders presumably rest with the corporation that signs their checks and provides their stock options. Google has an interest in making you feel that the internet is a confusing place since their search engine is one solution to the confusion. (However, if you rely on autocomplete, Google’s suggestions may not only be confusing; they may even be morally reprehensible.)

Still, Schmidt’s characterization of the internet as a place of anarchy is accurate. And as we seek to define digital culture and to discuss the cultural relevance of social media in this chapter, we must recognize that there is no grand plan. The only constant in digital culture is change, which may sound cliché, but the underlying ICT structures shift so often that it can be difficult for cultural trends to take hold.

Chapter 1 of this text defined society and culture in the context of the field of mass communication. It covered the distinction between interpersonal communication, organizational communication and mass communication, and then it delved deeper into concepts relating to mass communication. The purpose of the first chapter was to start a discussion about how evolving information and communication technologies (ICTs) can influence the mass media and contribute to social and cultural change in the process.

A Brief Overview

If you are anticipating a roadmap of neat, organized plans for how the evolution of culture on digital platforms will unfurl, you’re gonna have a bad time. Instead, this chapter offers a brief, lively discussion of how we define digital culture and what we might expect from it as it emerges in online spaces, mobile apps and platforms.

Additionally, this chapter includes a breakdown of the roles social media platforms may play in influencing culture.

If you acknowledge that cultures have always been in flux, then perhaps the concept of a digital culture emerging online amidst anarchy will look less like disruption and more like evolution (Spoiler Alert: Reveals the plot of The Last Jedi). However you classify it, the cultural impact of the merger of the mass media and digital networks is vast, and that is the topic of this chapter.

This chapter begins with a definition of “digital culture” that comes from the media studies portion of mass communication literature. Media studies refers to the broad category of academic inquiry analyzing and critiquing the mass media, its products, possible effects of messages and campaigns, and even media history. Chapter 2 then continues with a deeper discussion of identity in the digital age and covers privacy and surveillance as well as the praxis of digital culture as defined by scholars. The term “praxis” here refers to how a theory plays out in actual practice.

This chapter also identifies different levels of culture (a concept borrowed from anthropology) as they relate to cultural products reaching audiences through digital mass communication channels. In other words, we ultimately answer this question: If we take existing theory for describing the levels of culture and apply it to digital culture, what are some immediately recognizable traits?

Finally, social media are defined from a scholarly point of view with particular attention given to the cultural potential of digitally networked social platforms.

Digital Culture Defined

Scholars argue whether we can understand what the spread of digital networks will mean for relatively well-established cultures in the tangible world, or predict with any certainty how cultures will evolve on digital platforms. There are two basic schools of thought. The first argues that existing cultures might find themselves essentially recreated in digital form as more and more life experiences, from the exciting to the mundane, play out in digital spaces. The second school of thought posits that the dominant digital culture emerging now is a separate culture unto itself.

It seems likely that neither version of these imagined forms of digital culture will dominate; instead, we will likely see a combination of the two. Parts of existing culture will appear online as they do in the physical world and parts of digital culture will seem completely new, previously unfathomable because they could not or would not appear in the tangible world.

Before we delve in with prognostications about where digital culture is headed, let us first define our terms. Digital culture refers to the knowledge, beliefs, and practices of people interacting on digital networks that may recreate tangible-world cultures or create new strains of cultural thought and practice native to digital networks.

For example, an online fandom and a real-world fan club are both made up of people who are geographically separated but share a common interest. If a fan club were to “go online,” networked communication platforms might make the experience better than it was in the physical world. Before the advent of the internet, most fan clubs produced a newsletter, offered connections with pen pals, and provided early opportunities to buy tickets and merchandise. Online, fans can create deeper relationships with one another. They can connect and communicate on official channels or make their own unofficial groups where they need not communicate through a central authority or gatekeeper. Fan and star interactions can be direct, one-on-one interactions on multiple social media channels. There may be an official, organized fan group, but many other avenues can appear on relatively open platforms with few rules.

The cultural product at the core of a fandom might still be a “legacy media” product. Legacy media are any media platforms that existed prior to the development of massive digital networks. Yes, there are people who are “Instagram famous” or “YouTube” famous, but the biggest stars in our cultural world still have many ties to legacy media. Musicians, film stars and comic book heroes come to mind. What other types of “legacy media” stars have huge online fandoms?

Online fandoms may simultaneously expect less centralized authority over the fan experience and more direct access to their heroes. They often expect to see transparency during the creative process, such as Instagram or Twitter posts with “secret” messages for longtime followers or behind-the-scenes videos as albums and movies are made. Fandoms might demand to hear key information first or to have special access via social media.

Similar things could be said of fan clubs in the age of snail mail. Essential elements of the culture of fandom — gaining access to artists and finding friends in a community — have not changed as much in kind as they have in degree.

Is this an example of the transition of an existing cultural form (the fan club) to digital environments, or is online fandom something truly different from a snail mail fan club? This is a good question to debate in the classroom.

It is worth noting that there are also niche fandoms that probably would not exist without the aid of digital networks. With virtually unlimited communication space, there is room for incredibly rarified fan groups to form on platforms such as Tumblr, and they are not always socially positive communities. In many cases of hyper-specific fandoms, it is difficult to argue that these cultures existed in the physical world and simply “moved online.” Being digitally networked is what makes it possible to find people with particularly narrow shared interests, for better and for worse.

Digital Dynamic

Even with the presence of niche online groups, digital culture cannot currently be separated from the influence of physical-world cultures. We can say two things about the relationship between online and physical-world cultures at this time. First, the growth of interaction on digital networks influences “traditional” cultures. Second, longstanding cultural traditions are influencing digital culture as it takes shape. The ethics and norms established in the physical world shape our views about behavior and values in digital networks. The term norm refers to a behavioral standard. Mutual influences of what is considered “normal” in online behavior and well established physical world norms are emerging in a dynamic fashion. Sometimes they clash.

One example is online dating. Dating in real life (IRL) is changing as more and more people use dating apps and websites. Previously, dating was limited to the people you were likely to meet. You could meet friends of friends. You could meet people at school, at parties, at bars or on blind dates. Your options were limited geographically and by how outgoing you were, how much time you wanted to spend looking, and who you trusted to set you up. The personal ads in newspapers were often considered sad places for losers. Using a mass medium to find your true love was often considered a risky last resort.

When online dating first became available, it was often compared to posting and perusing digital personal ads. This was a cultural perception based on previous experiences, behavior and expectations from a pre-Internet culture.

Over the course of approximately ten years (1998-2008), what once was considered odd, creepy or desperate in many parts of the Western world came to be considered commonplace. Apps and sites like OkCupid, Tinder, Match.com and eHarmony have millions of users. Culturally, many of us have accepted this new digital form of dating. It’s not for everyone, but online dating does not carry the stigma it once did.

Even Tinder, which has a reputation as a “hook-up” app, maintains popularity and cultural significance as it is referenced often on other media platforms.

Whatever it may be in a given culture, sexual morality still exists, even if new technologies make hooking up easier and new capabilities challenge old norms of what dating should be.

This is the dynamic at the heart of this chapter. Digital technology can influence knowledge, beliefs and especially practices around dating. This can, in turn, shape the way people think about dating in general, not just in digital environments. The “old” cultural norms and morals can still be applied to judge those who use digital apps for casual hookups, but the new culture can push back, so to speak, and change how people think about dating even if they never use dating apps themselves.

We have discussed how the digital culture and physical world culture dynamic functions, but we have not yet defined digital culture. For that, we must look to scholars who have spent years trying to pinpoint what emergent digital culture seems to be.

Individualization, Post-Nationalism, And Globalization

We turn to Mark Deuze, a scholar from the University of Amsterdam, for a complete definition. He seeks to provide a preliminary definition of “digital culture” in his 2006 article, “Participation, Remediation, Bricolage: Considering Principal Components of a Digital Culture.”

In his analysis of academic literature, Deuze finds that scholars often make assumptions when trying to explain how digital culture works. The main he identifies is the idea that culture moves to digital networks more or less intact. There was, a decade ago, a lack of explanation about what happens to culture in digital environments.

How much might culture change when certain practices move online? How often can existing cultural beliefs and expectations be transferred intact? Deuze does not think digital culture is merely a recreation of physical world culture in online spaces, but he does not have a good answer for what has been emerging. He analyzes independent media sites, blogs and radical online media outlets to see what these new forms of communication demonstrate about digital culture.

That these forms are not meant to represent all culture but rather a cultural vanguard. They are (or were) the tip of the spear of newly evolving digital cultures. These sites are often progressive politically, so this is not as much a prediction of what will happen with all digital culture as it is a discussion of what is possible. Deuze maintains that the real practice of digital culture is “an expression of individualization, post-nationalism, and globalization.”

Individualization

Deuze finds individualization in blogs most frequently written by one person and focused on a specific topic or small geographical region. Individualism, as it is used here, refers not only to an individual’s ability to act as their own publisher online but also to a social condition in which individuals are free from government control. It means that even in authoritarian nations such as North Korea, Russia, China and Iran that try to control the behavior of their citizens, individuals may seek freedom of expression on the internet, although it comes at a greater risk.

Beyond Deuze’s observations, evidence of individualism online comes from partisan news sites such as The Drudge Report and HuffPost. Both are named for individual founders. They are digital mass media outlets that started largely as personal points of view.

The importance of individualized expression on social media is clear. We appear as individuals on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat and Tumblr. This increases our reach. Each of us can potentially connect with every other individual on a given social media platform, but these platforms also raise questions about surveillance and privacy.

Digital Individualism Versus Privacy

Eric Schmidt once said about online privacy and Google, “If you have something that you don’t want anyone to know, maybe you shouldn’t be doing it in the first place.” While this might make sense in a free society, there are many places in the world — North Korea for example — where government surveillance can utilize corporate invasions of privacy to crack down on dissent and severely limit freedom.

Suppose someone living in North Korea would like to use a social media channel such as Twitter to connect with like-minded people without government officials finding out. Should Twitter protect those users? What if a state threatens legal action or violence against Twitter employees? Would social media channels give up their users?

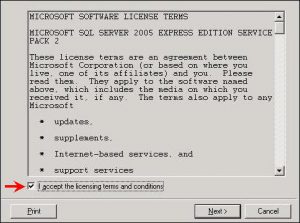

There is a difference between government surveillance (that is, state-sanctioned data gathering and analysis on massive scales) and corporate data aggregation for targeted marketing purposes. Usually, by accepting the Terms and Conditions of apps and web services, you opt in to having your data stored, crunched and analyzed by corporations. Legally, you are responsible for that decision. Technically, the data gathering platform is not supposed to identify you as an individual, but so-called “safe harbor” laws can be ineffectual.

Should Google protect your searches and refuse to divulge information about your habits to governments, even if they share that data with other companies for marketing purposes? Should Google give you a way to hide your online activity? Is there a way for the liberty-loving Southeast Asian to have his privacy protected while still enabling Western governments to watch out for terrorists? These questions relate to larger issues of freedom and individualism in digital culture.

Throughout its history, the United States of America has taken pride in its First Amendment and the rest of the Bill of Rights as guarantees of liberty. After the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, many Americans accepted new levels of scrutiny, particularly in digital environments. Support for strong leaders increased until very recently. Concerns about the global rise of authoritarianism have people questioning government surveillance and corporate surveillance as they may limit our ability to engage as individuals in digital culture.

Eric Schmidt’s statement implies that privacy in digital networks is limited. This sentiment is echoed by Mark Zuckerberg, who has suggested that privacy is dead. What this means is that physical world behavior is expected to adapt to the demands of digital culture because the capabilities of digital culture also carry with them unique risks that we are not necessarily adapted to deal with.

Our experience with the anarchy of online mass communication platforms is quite limited. As we learn what government surveillance and corporate invasions of privacy are capable of, it may continue to deeply affect our physical world behavior.

Many would agree with the sentiment, “If you do nothing wrong, you have nothing to worry about,” but even advocates for a more open digital society want their privacy. Zuckerberg bought several properties around his house to keep his physical location secure. Eric Schmidt does not want people to know where he lives. He generally does not invite the public into his private life, and, one might assume, does not want people to examine why his former wife said she felt like a “piece of luggage” when married to him. Such information about Schmidt’s personal life is easy to find online and could be used against him, but should we care? Does it matter in the broader cultural sense?

This text argues that privacy does matter. The vast majority of us are not using digital platforms to break laws or to interact in negative ways with others and yet we still have aspects of ourselves that we would like to remain private. Has a parent or guardian ever snooped on your Facebook account or followed your Instagram? We have incredible freedoms and amazing digital communication capabilities as individuals living our lives in the new digital culture. It comes with a price we have yet to grasp.

Terms and Conditions

The film Terms and Conditions May Apply details the ways our private information, such as our emails and texts, can easily be related to our public information on social networks.

The filmmakers note that the knowledge and hardware needed to snoop on people are bought and sold all over the world and are often unregulated.

Are we becoming more open because of the ways social media function? Is there anything wrong with that? Are we surrendering our privacy in ways that cannot be undone?

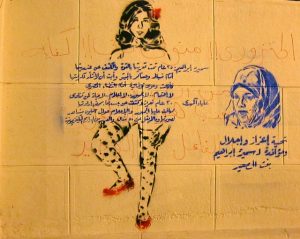

One of the major cultural challenges of the network society will be to deal with people in power who would like to use our information against us as a means of control. It has already happened in some of the countries where the Arab Spring revolutions took place (Egypt, for one).

You never know what you might need to protest in the future, but we’re beginning to see tools deployed to pre-empt protest and other acts of dissent. What this means for our efforts to define digital culture is that digital culture can free us as individuals, but it can also imprison us.

We can use the internet and smartphones to help us to get questions answered and to draw attention to ourselves in good ways. We can coordinate with others for fundraisers and to have parties. Digital communication networks are amazingly sophisticated tools that can help us connect as individuals to form groups to celebrate all sorts of interests, political and otherwise.

On the other hand, if individuals believe they have no privacy, digital networks could become virtual wastelands where innovative collaboration is hindered and where corporate commercial speech and government surveillance dominate.

Capitalism depends on risk-taking, and if you kill risk-taking online, you have hindered the entrepreneurialism that the network society offers. We scholars will study for decades to come how individual behavior changes and how relationships morph in a digital culture that discourages behavior we want to keep private while simultaneously encouraging levels of sharing that border on exhibitionism. How can we maintain privacy and gain attention, which is so often the currency of the open Internet? This is an interesting dilemma that arises in an individualistic digital culture.

Post-Nationalism

Post-nationalism is another aspect of digital culture that Deuze notes in his article. It may seem unrelated to our previous discussion of individualism and privacy in digital culture, but in fact, it is an analysis of the ways individuals represent themselves online.

Most simply, “post-nationalism” in digital culture means that one’s country appears to matter less as an influence on behavior and values online than it does in the tangible world, perhaps because we can be free of our national identities when engaging in digital networks with people from around the globe.

This does not mean that we should expect to see an end to nationalism in the tangible world. Quite the opposite seems to be true: As post-nationalism appears in digital spaces, nationalism is on the rise in global politics. It might seem odd that people drop their nationalism online but demand it in physical spaces, but if you look at the way culture is expressed online, it is clear that for many people their nationality has little to do with their online identities.

For example, your country may be important to you, but it may not be one of the ways you define yourself in social media environments. You can love America without talking about it all of the time on Facebook or Twitter. Remember as well that national boundaries may be felt more readily in the daily lives of Africans, Asians, Europeans and others living in nations that are geographically smaller, more tightly packed and culturally distinct. In digital spaces, these cultural differences can evaporate.

Although war and immigration are highly influential on the current cultural climate in the physical world, the perception of evaporating culture in networked spaces may help drive the sense that physical world cultures are being threatened.

Recent political developments, however, make it somewhat more difficult to think of digital culture as post-nationalistic given the rise of online nationalism — particularly white nationalism in Europe and the United States. White nationalism is a brand of nationalism related to white supremacy, but it is an identity connected to the nation-state nonetheless. A nationalist’s primary modus operandi in digital culture may not reflect what nation states ultimately become in the 21st century, but rather what they wish it were. Even so, there is evidence that some factions will use digital spaces to promote a return to nationalism.

Does this mean that post-nationalism in digital culture is a false notion conceived in the early 2000s that has no bearing on culture today? Perhaps, but it is more likely that we are seeing a backlash against the rise of a global post-nationalist space online.

Globalization

Digital culture, Deuze posits, reflects a globalized or globalizing world. Behaviors, interests, and relationships cross international boundaries. The economic structure of digital networks, including the mass media system, is global. For example, multinational conglomerate corporations tend to dominate the media industry, not just in the United States but around the world. Books, academic articles and simple infographics show that most mass media companies fall under the ownership of large corporate firms. It is not accurate to say this represents all media or that “the media” are being controlled, but it is accurate to say a significant level of influence can be attributed to a handful of media corporations in most developed parts of the world.

Mass media consumers should be aware of the environment in which media products are produced, but this is not to say that the globalization of mass media is always a negative thing. When it comes to culture, globalization has its supporters. Here is a site in English about K-pop music. The music comes from Korea, but the fanbase is spread worldwide, and the site can reach a global audience only because of the global nature of digital networks. It works only because computer servers are connected by wires all over the globe to make this bit of culture, like many others, available to the entire globe.

There exists a global point of view in both the physical world and in digital culture which is open to all kinds of cultural production as long as it is interesting, funny and shows great talent. There are videos that go viral globally, although it is not always clear why. (If we had the formula, we’d include it here.) All we can say at this time is that you can reach the world with any online message and, for whatever reason, some things are globally likable and “shareable.”

A Place Called Gangnam

Humanity’s recently developed ability to develop a globalized point of view and to establish a common digital culture is the reason you have heard (and likely tired) of “Gangnam Style.” Ironically, PSY, who performs the song, is kind of an anti-pop star within Korea. The song makes fun of the country’s higher class, a conspicuously wealthy subculture from a place called the Gangnam District. But PSY is a global success. He is popular, many argue, because he is quite funny and because he is not the prototypical K-pop hero. He comes from a particular national cultural tradition, but he also transcends it by being absurd. Thus, as a distinctly individual performer, he personifies a type of post-nationalism and the globalization of digital culture.

Individualism, post-nationalism and globalization go a long way toward defining the emergent “digital culture.” For more information, consult Deuze’s original article.

Digital Culture In Practice

Deuze makes one more observation not about what digital culture is but rather how it works. Deuze argues that the production of digital culture will be carried out through participation, remediation and bricolage.

Participation means that every individual will have the ability to contribute to online media. Professionals and amateurs will work together much more often than they did on “legacy media” products and projects.

Because people do not want to work for free, they will not flock to an online platform simply because it has been opened up for contributions. If anyone could build a Facebook, there would be hundreds or even thousands of competing platforms. As it stands, there are perhaps ten major social media platforms worldwide, if “major” means they are home to more than 200 million members.

It is also clear from social networking sites, Reddit, and similar social news sharing sites that people will contribute to a platform even if it is not necessarily well-policed or easy to use. In digital culture, it helps to be the first to be big. Success breeds success in an economy based on attention, and what dominates tends to be emotional issues, as satirized here.

Consistency also seems to help, but what matters most is the ability to consistently draw an audience. Think of a person trying to become a YouTube influencer. They must publish interesting content regularly for months or even years before they develop a following that they might be able to sell to advertisers. Once the YouTube star does begin to peddle products, they run the risk of alienating a portion of their audience.

Participation is an essential part of digital culture. It can be easy and fun to do it for free. If you want to make a career out of it, it takes professional-level commitment, and the resulting content often favors what is popular and emotionally gripping rather than what is informative or socially beneficial.

Remediation means that old media are made new again in digital spaces. Television becomes YouTube. Radio becomes podcasting, Spotify and Pandora. Newspapers become … online newspapers! The new media take elements of the old media and repurpose them, while “legacy” media firms copycat digital media trends, buy out media startups, or try to forge new paths at significant expense.

In the practice of digital culture, media are remade in digital environments in a process that combines the appealing parts of existing forms of media with additional functionalities made possible by new ICTs and digital networking capabilities. The author’s own research argues that attempts by legacy media organizations to create new businesses online face many institutional hurdles. Remediation is constantly happening, but that does not mean existing media companies can determine how to monetize the practice in a sustainable way. We should expect considerable remediation innovation to come from startup companies and individual tech entrepreneurs with few ties to legacy media.

A good example of remediation is taking classic movies or video games and showing them to young people to record their reactions for YouTube. Reaction videos of all kinds take media products people are familiar with and show them to the unfamiliar so that viewers can judge their reactions. This new media product repurposes old content with an added element designed to pique our interest; however, remediation does not always add much value.

Bricolage is a French term not easy to translate literally to English. A translation offering deep context might be: Do it yourself by combining elements found elsewhere. Much of digital culture is an amalgamation of existing content and new cultural work being done at home by people with amateur skills and affordable but capable tools, such as smartphones and tablet computers. Even basic tools are quite powerful. Smartphones come with front- and back-facing cameras as well as HD-quality video. The computing power of a smartphone is more powerful than a mainframe computer was 70 years ago. Independent producers have video and audio editing software options and can create professional looking, popular media products on their own with little formal training.

Professionalism

What is formal training for, then? It prepares you to transition from making professional looking and sounding media products once in a while to consistently making professional quality media. Formal training prepares you to think strategically about where industries are going so that you know not only how to make mass media products but where to place them and how to use and possibly develop your own communication platforms.

Formal training includes an education in history and ethics. Amateur producers are skilled at chasing trends and gaining popularity, but they often ride cultural waves that last from a few months to a couple of years. Planning for multiple media shifts and seeing digital cultural trends as or before they emerge requires an education in more than the tools and tricks of the trade.

Deuze In Sum

Deuze’s analysis suggests that barriers between professionals and amateurs are breaking down. Old media are made new again in digital culture, through a process of making digital media collages, so to speak. (The word “bricolage” is related to “collage.”)

Thus, in practice, digital culture is democratizing (though not fully democratic, of course). Amateurs can create media products that challenge the popularity of cultural production made by corporate conglomerates valued at hundreds of billions of dollars. What emerges in terms of popularity, though, is not necessarily high in quality or accuracy. Quality and accuracy are the hallmarks of professional communication (although not all professionals behave as they should).

Levels Of Culture In Digital Media

Let’s take a step back and look at the definition of culture again. In the first chapter, this text defined culture as being made up of the knowledge, beliefs and practices of a group of people. We need to tweak that definition a little. It is more accurate to say that the knowledge, beliefs and practices of a massive group of people at a certain time and place defines common culture.

Three levels of culture exist in anthropology literature, and they apply to the ways culture is expressed in the mass media. The three levels of culture are personal culture, group culture and common culture (similar to pop culture).

Any kind of culture, whether it is personal, group or common culture, relies on shared knowledge. There must be shared experiences and shared stories about those experiences for us to have a common culture. If we did not have shared experiences, cultural references would not make sense. Thus common culture can be arrived at when individuals and groups tell the same stories, or when mass media reach mass audiences with the same messages at the same (or about the same) time.

The more people who know about a song, film, work of art or event with cultural significance, and the more information that they know about it, the more likely it is that event will become part of the common culture. The mass media influence common culture, although it is not correct to say that they directly shape it. There are many other institutional influences on common culture such as governments, churches, families and educational systems.

In fact, messages in the mass media may not be as influential now as they were in the mid-20th century when millions of people watched the same TV shows each week at the same time and read the same major metropolitan daily newspapers and national magazines. Demassification has affected the ways common culture is established and fed.

The mass media influence may have less power to influence common culture directly, but it is still relevant. Think about any major global news event of the past few months. When an event is big enough that it is shared across all media platforms, especially cable television, broadcast television and social media channels, it can form a piece of common culture. If several events occur or if an event has a broad enough global impact, it can enter the global collective memory, the shared cultural memory of a group of people.

Group culture is what we used to refer to as a “subculture.” It is the knowledge, beliefs and practices of a subset of people considered to be part of a larger culture. Group culture is distinct in some ways from the shared, broader common culture. Group culture might center on religious beliefs and practices, ethnic norms and interests, or food, music and other forms of material production. Groups can be as large as all Chinese-Americans and as small as the remaining St. Louis NFL fan culture.

You have a say in defining your personal culture — the knowledge, beliefs and practices held most dear to the individual. You may find yourself identifying with many group cultures or taking most of your interests from the dominant common culture. Do you take your cultural cues about what to think about and talk about from television, social media or small group cultures with which you identify? This much is your prerogative. You can choose your personal culture. It is based both on what you believe in and what cultural products you consume.

America, ‘Merica, Los Estadas Unidos, Etc.

There is a common culture in America, but there is no single, dominant, common culture across global digital networks. There may be a tendency for people to believe that the group cultures they interact with most often online constitute the “real” digital culture, but as yet there is no clear consensus about what our shared digital culture is or even if we will develop one.

Algorithms in search engines and social media platforms determine much of what we find when we search the internet and what we see when we look at news and information feeds from our friends. Do algorithms constitute common culture? They may shape it, and they may be influenced by user preferences, but they are not always designed for truth, accuracy or information literacy. They are most often designed to give consumers whatever makes them consume more of what the platform wants them to consume. Google usually wants you to spend money with its advertisers. Facebook wants your time and your data so it can sell your information to third party advertisers.

What shapes digital culture is often in a “black box”: It is the proprietary information of very large corporations, and the public may or may not have access to the code. Even if we did have it, it would be difficult to explain exactly how algorithms work. There are times when the corporations that deploy algorithms seem surprised by how they function in the hands of massive numbers of users.

Major events that cut across algorithms and show up on almost everyone’s news feed and in almost everyone’s search results are still likely to have an impact on common culture. Major events are likely to shape personal, group, and common culture if they are significant enough. What kind of cultural impact does a given event have? It depends.

The impact of a school shooting near Miami might be felt differently in Florida than in California because of proximity and because the gun laws in each state are quite different. In other words, something can enter the common culture but still be perceived quite differently by individual members of the public.

Norms

By now you should understand that the cultural impact of messages in the mass media at each level — personal, group and common culture — is related to the shared knowledge that existed before the event.

Events are often going to be perceived differently by people identifying with different small group cultures within a larger common culture. Events will usually be interpreted differently by individuals within a small group culture, depending on an individual’s beliefs about and personal experiences with the issue at hand.

A person’s response to current events as they appear in the mass media is also related to the existence and strength of shared beliefs about the way they think things ought to be. We call those beliefs cultural norms.

There is no single, agreed-upon set of norms that everyone in a given group culture adheres to. If you have lived your whole life as part of the dominant culture, and you do not recognize the existence and struggle of various cultural groups, it can be difficult to recognize reactions in digital media spaces that do not relate much to what you see in your physical world. Conversely, if you have grown up being oppressed as part of a small group, you may find it hard to understand how others identifying with the dominant portion of a common culture can miss the cruelty present in some cultural norms they don’t think twice about.

Exposure to other groups’ cultures in a network society can bring about both greater understanding and greater anxiety. This is something that will be worked out, for better or for worse, over the next several decades as digital culture evolves. Figuring out how groups with different cultural interests, norms, and values can get along while being constantly exposed to one another’s views in the free-for-all of network society is the challenge of emergent digital culture.

One response is to run to echo chambers, to partisan spaces that feel safe for certain group cultures and for our personal cultural beliefs and priorities, but this practice can only deepen the divide between cultural groups.

In the early years of working to establish a common culture in the network society, we have managed to inundate ourselves with information from all manner of cultural groups and to isolate ourselves from views that contradict our own group cultural norms. This is anarchy. This is culture without a strong social structure to hold it together.

The question facing mass communication scholars that members of our common culture also face is whether the institutions of the physical world can or should try to control how digital culture is shaped. You have the power to decide if digital culture should be regulated and how. This may be the most important civic responsibility you have, but it is also a matter of cultural power.

Social Media And Social Capital

What do you think it means for society that networked communication platforms can make anybody a mass communicator? One answer is that there is great potential for social change because society, as Dewey said in Chapter 1, is not just transmitted by communication, it exists in it.

That means every individual with a computer or a smartphone has the potential to disseminate messages that influence broader society. Think of the Arab Spring revolutions of 2010-2012. Think of #Ferguson protests in the summer and fall of 2014. Think of the way candidate Donald Trump bypassed mass media outlets to reach voters and to set a separate news agenda in 2015 and 2016. Individuals and small groups are now able to coordinate and to lead social movements using networked communication technologies.

You have probably heard the term “social movement.” In a sense, a social movement is a change in society brought on by communication. What is different about the world of networked communication is how interpersonal messages and message campaigns can shift in an instant to being mass messages or massive campaigns. This makes digital networks battlegrounds because networked public communication platforms are centers of power now more than ever.

Just as they can influence and even disrupt social structures, individuals and small groups can shape culture using social media channels. This makes our communication system as ripe for abuse by outside forces as it is for use by legitimate citizens. Governments, corporations and rogue dictators all have an interest in learning our secrets, and they could potentially hold them against us.

We cannot underestimate how important this is will be in the mass communication field. Individual, group and broader social secrets — including consumer behavior, political behavior and even personal thoughts and interests — are easier to discern and possibly manipulate than ever before because of the vast amounts of data collected about us from our social media and other internet habits. This can have a profound effect on our behavior and on our society, and we are not prepared as a society to defend ourselves against attacks.

Before you get discouraged about digital culture and privacy, and before you get inundated with all of the possibilities and implications of digital culture, consider Clay Shirky’s Ted talk, “How social media can make history.”

Shirky outlines the power of social connectivity and applies the concept of social capital. The basic definition of social capital is the potential to get help, not just financial assistance, from the people around you when needed. Social media platforms can be great places to build social capital. Thus, they have the potential to be constructive or disruptive. It depends on how you use them. Watch the video for a complete definition.

Interpersonal communication, organizational communication and mass communication are separate areas of academic interest, as stated in the first chapter, but our ability as consumers and as producers to alternate from one to the other is as powerful as it has ever been. Being connected to each other almost at all times by digital networks creates the capacity for relatively quick mass social action. People are beginning to use this power to pull society in different directions. Large numbers of people can be organized and we could see social shifts and rifts develop more quickly than they can be put back together. It will be up to individual users and groups of users to decide how to respond to such social and cultural changes.

Participatory Media

A major shaper of culture and society is the news media. There will be separate sections on the evolution of news in later chapters, but in the context of digital culture, it bears noting that the role of news media within broader media landscapes is also shifting.

Apart from the ability of social movements and cultural movements to arise and take shape on social media platforms, there is also the potential for public opinion to be influenced quickly and deeply when mass media outlets operated in the same digital networks as influential individuals and groups.

You may contribute to news information by volunteering. One of the biggest stories to gain national attention in 2014 that was filmed and posted by a citizen journalist was the story of Eric Garner, who was seen being put into a chokehold by NYPD Officer Daniel Pantaleo. Reports said that Garner had asthma and that he died of a heart attack. Here the term “citizen journalist” refers to a person who is not a paid professional but who delivers news to audiences nonetheless.

It is doubtful that the story would have received national attention had it not been for the video bystander Taisha Allen took with her mobile phone. When she shared that video, and it went viral on social media channels, she made the mass media story possible.

Allen probably had several reasons for sharing the video of Garner, and she was probably aware of the potential social and cultural impact of the video. You do not have to be a media literacy expert to know that such a video would receive broad attention and generate controversy. Allen chose to share the video because she thought people needed to see what had happened.

Further solidifying the cultural significance of the video, within days of the story breaking, Spike Lee had re-cut a scene from his groundbreaking film Do the Right Thing where the character Radio Raheem is choked to death by an NYPD officer. He interspersed his original film clip with bystander video of Eric Garner’s death. This almost instant connection between a post made by a citizen using social media and a bit of modern classic film speaks to the rising power and cultural influence of amateur media. Individuals can affect major producers in a mutual effort to shape social norms and structures as well as cultural influences.

We should expect more and more professionals to make these kinds of connections with amateurs and bystanders in the future. Mashups of professionally made mass media messages and citizen-generated messages are likely to proliferate. Can you think of video footage from individuals present during major news events that shaped the news and public opinion?

The events in Ferguson, Missouri followed a similar path as the Eric Garner story: Social media accounts of the killing of Michael Brown were shared virally almost immediately after the incident. Social media activity on YouTube, Twitter and other channels helped shape the way events unfolded. This drove the way the story was covered in the national media in the early reporting, but backlash inevitably followed.

Much of the work done by citizen journalists will be controversial. Media professionals working in news and other fields will have to use discernment in deciding which views to share because in a sense sharing is promoting, even if one disagrees with the sentiment of the tweet, video, or post.

No piece of media that is meaningful on a cultural level is going to be captured and disseminated with universal agreement about its importance or its meaning, but for society to function and for culture to serve its purposes we need to agree in a general sense on what’s real and what is not. The real danger in the rise of the power of individuals and small groups in digital culture is that they can pull larger groups away from looking for fact-based discourse.