Chapter 9 – Tools and Tactics for the PR Toolbox

In the 1960s, researchers Johan Galtung and Mari Holmboe Ruge examined news stories worldwide to determine their similarities (Galtung & Ruge, 1965). Their seminal study created the first news value list, which is still referred to today by journalists and strategic communication professionals. (See the University of Oxford’s paper on Galtung and Ruge’s research for more information.) News values have evolved over time, and there is much debate over whether journalists should consider other criteria to select newsworthy content. (See Dr. Meredith Clark’s article on considering a new set of news values.) Currently, eight values are used to determine a story’s newsworthiness (Kraft, 2015). Some of the values’ names may differ slightly in other sources, but their meaning is the same.

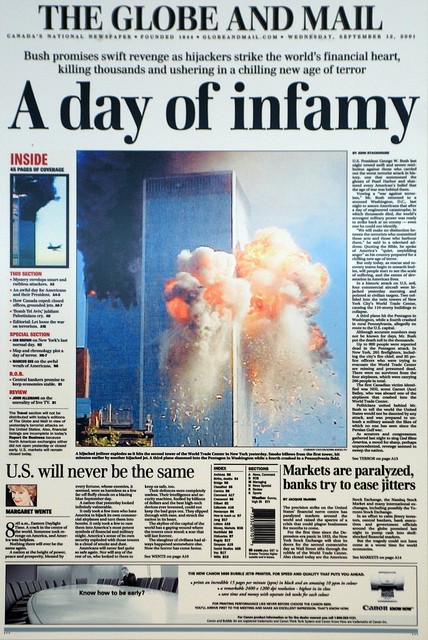

Immediacy/Timeliness

Events or stories that have recently taken place or will happen in the immediate future have immediacy or timeliness. Breaking news stories or stories about unexpected events that are developing are good examples. Media gatekeepers deem these stories so important that they often interrupt regular television schedules to immediately give audiences the information. Recent happenings typically carry more news value than less timely events.

Timeliness also takes into consideration factors such as seasonal events, commemorations, and holidays. A strategic communication professional may pitch an activity that connects with this type of timeliness—for example, a fundraiser that distributes toys to low-income children during the holiday season.

Proximity

Proximity considers the location of the event in relation to the target audience of the media outlet. Audiences are more likely to pay attention to stories that take place in their local communities. For example, a news station in Ohio usually wouldn’t cover day-to-day events at the Indiana State Fair. However, happenings at the annual Ohio State Fair always get daily coverage in central Ohio news outlets.

Human interest

Stories that are emotionally compelling capture the audience’s attention and appeal to their attitudes and beliefs. Feature articles often are good examples of human interest stories when they depict a person, organization, or community in a way that triggers an emotional connection between the audience and the characters. Other examples are a behind-the-scenes look at the life of an athlete or the story of a person struggling to overcome an obstacle.

An example of a human interest story that contains strong emotional elements is that of Leah Still, daughter of National Football League player Devon Still. Leah captured the hearts of many when news outlets began to cover her battle with cancer in 2015 when she was four years old. Many people admired Leah’s positive attitude and determination to beat her illness. Now cancer-free, Leah continues to be an inspiration to thousands of people. For more information about this story and its human interest elements, take a look at this video:

Leah and Devon Still’s story (Source: ABC’s Good Morning America)

Currency

Topics that are trending in news media and other media, such as Twitter and Facebook, are considered newsworthy. “Hot topics of the day” or stories that are in the general public discourse are other examples. In 2015, many media outlets covered a story about a meme featuring a dress that appeared blue and black to some people and white and gold to others. The phenomenon was dubbed “dressgate” and went viral on social media. Since many people discussed and debated the color of the dress, some news outlets decided to cover the story. However, topics that have currency value generally have a short life span in the news cycle because they are discussed only briefly by the public. Click here for more information on the “dressgate” discussion.

News value types (Part 2)

Prominence

Stories that feature well-known individuals or public figures such as politicians and entertainers carry news value. News outlets covered the story when model Tyra Banks completed a management program at Harvard’s School of Business in 2012. Banks’ celebrity profile raised the news value of a story that would have received little or no attention had it involved just about anyone else.

Impact

The United Kingdom’s vote to exit the European Union in June 2016 had global implications, and many media outlets in the U.S. and abroad reported the story. However, British news stations such as BBC News and Sky News covered the event more extensively than American media did because the decision impacts Britain’s economy and citizens much more so than Americans. Generally, people are more likely to care about stories that directly affect their lives; therefore, media gatekeepers often devote more time and resources to stories that have implications for their respective audiences.

Novelty

Stories that are odd, unusual, shocking, or surprising have novelty value. An example would be a story about an unusual animal friendship, such as that between a dog and a deer. Because such a friendship is not a normal occurrence, it sparks the curiosity of audiences. In 2015, CNN covered a story about a weatherman who was able to correctly pronounce the extremely long name of a Welsh village. Take a look at this clip of the story:

Weatherman pronounces long village name (Source: CNN)

Conflict

Strife or power struggles between individuals or ethnic groups or organizations contain a conflicting value and often grab the attention of audiences. For example, stories about war, crime, and social discord are newsworthy because their conflict narrative spurs interest. The continuous coverage by U.S. media outlets of worldwide terrorism is another example. Stories about major sports competitions, such as the National Basketball Association finals or the Super Bowl, also contain a conflict element because teams are vying for a prestigious title.

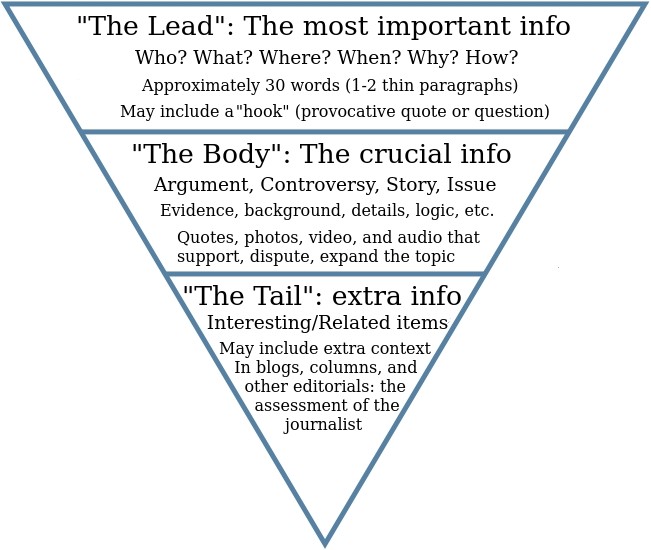

In general, news stories are organized using the inverted pyramid style, in which information is presented in descending order of importance. This allows the audience to read the most crucial details quickly so they can decide whether to continue or stop reading the story. From an editing perspective, using the inverted pyramid style makes it easier to cut a story from the bottom, if necessary. Invented more than a century ago, the inverted pyramid style remains the basic formula for news writing (Scanlan, 2003).

Long Description

The Lead: The most important info

- Who? What? When? Where? Why? How?

- Approximately 30 words (1-2 think paragraphs)

- May include a “hook” (provocative quote of question)

The Body: The crucial info

- Argument, controversy, story, issue

- Evidence, background, details, logic, etc.

- Quotes, photos, video and audio that support, disputes or expands the topic

The Tail: Extra info

- Interesting/Related items

- May include extra context in blogs, columns and other editorials: the assessment of the journalist

It is important to note that some news stories do not strictly follow the inverted pyramid style, although the lead for a hard news piece always does. Furthermore, not everyone in the journalism field embraces the style; some detractors believe it is an unnatural way to engage in storytelling and present news to the public. Yet, proponents believe it is an efficient way to organize and share information in a fast-paced society (Scanlan, 2003). Therefore, it’s important for students to learn the style; one good way to do so is to regularly read hard news stories and pay attention to how the leads are structured. The lead (also known as the summary lead) and the body of the inverted pyramid style are discussed in the next sections.

A summary lead concisely tells the reader the main idea of the story or conveys its news value. Most journalists and editors believe that the lead should come in the first sentence or first few sentences of a hard news article. Reporters use the term “burying the lead” or “delayed lead” to describe one placed later in an article. A buried lead may give the impression that the writer wasn’t able to determine what the real newsworthy material was, and can, therefore, reflect poorly on his or her journalistic judgment. In features or other soft news stories that use more dramatic storytelling techniques, the lead sometimes is buried in order to increase suspense or add an element of surprise.

A summary lead should address the following questions:

- Who is the story about? or Who is involved?

- What is the story about? or What happened?

- When did the event take place?

- Where did the event take place?

- Why did the event take place?

- How did the event happen?

Keeping the 5Ws and H in mind when writing a news story will help you organize the content and find a focus for the article. News judgment consists of figuring out the organization of these aspects of the content and prioritizing them in terms of their importance. It’s not necessary to cram the 5Ws and H into one sentence for the lead; however, the lead usually should contain information about the Who and What.

Take a look at the lead in this article from the Washington Post.

Now, let’s answer the 5Ws and H for the lead:

- Who? Female undergrads

- What? Claims of unwanted sexual advances

- When? 2015

- Where? Universities

- Why?

- How? Large study

In this case, the Why of the story is not addressed in the summary lead, perhaps because of the complexity of the issue. Still, the reader can easily understand the main idea of the article. When you’re practicing writing summary leads, remember to keep the sentence(s) relatively concise, with no more than 30 words.

Once you’ve created the lead, give the reader more information in the body of the article. This is your opportunity to elaborate on what else you know about the story. In keeping with the inverted pyramid style, present the information in decreasing order of importance, not necessarily in chronological order. The least important details should appear at the end of the article, where they could be omitted by an editor if necessary.

Use direct and indirect quotes from sources to tell the reader the origin of the information (there is more about this below), and remember to maintain an objective tone. Use the third person; avoid pronouns such as I, me, you, or us that are more suited to opinion pieces. Use short, simple sentences and organize them into paragraphs of no more than three or four sentences.

Indicate the source(s) of the information presented in the article through attribution, which typically takes the form of paraphrases as well as direct and indirect quotes. Attribution is very important in media writing, as it helps to establish an objective tone and adds credibility to an article (Harrower, 2012). Attribution also explains how the writer retrieved the information and why a particular source was quoted. Most of a story’s major information should be attributed, through phrases such as “she said” or “according to a recent report.”

Attribution can be placed at the beginning of a sentence to introduce information or added after a statement. Pay close attention to verb tense and choice when attributing sources. For example, the most common verbs used for attributing human sources are “said,” “stated,” and “asked.” For records or documents, use “reported,” “claimed,” and “stated.” Direct quotes should be surrounded by quotation marks and include the source’s exact words. Paraphrased statements and indirect quotes should not be placed in quotation marks.

Here are examples of attributed statements:

- “The libraries are usually crowded and filled with students around this time in the semester,” said Laura Skyler, a sophomore at The Ohio State University.

- A heavy cloud of smog hung over the city Wednesday, National Weather Service officials said.

- According to a statement from the White House, the president will announce his pick for the vacant Supreme Court seat on Monday.

When initially referencing a human source, include the person’s full name. Use only the last name for subsequent references. Use this CNN article as an example.

Include important qualifiers with the first reference to demonstrate that the source has expertise on the topic. For example:

- “Using Twitter in the classroom actually enhances student engagement,” Jasmine Roberts, strategic communication lecturer at The Ohio State University, said.

Notice that the direct quote with attribution uses the qualifier “strategic communication lecturer at The Ohio State University” to indicate the source’s credibility.

Qualifiers are also used to explain a source’s relevance to the topic. The following example might be used in a news article reporting on crime.

- “It was just complete chaos in the store. The police were trying very hard to catch the shoplifter,” eyewitness Angela Nelson said.

The qualifier “eyewitness” helps to establish Nelson’s relevance to the narrative.

Finally, attribution should flow well within the story. Avoid using long qualifiers or awkward phrases.

A headline concisely states the main idea of the story and is further elaborated on in the lead. It should clearly convey a complete thought. Headlines have become increasingly important in today’s society; people tend to look only at headlines rather than reading complete stories, especially online. An effective headline encourages the reader to take the time to read the article.

Print versus web headlines

Print headlines tend to be concise (using fewer than six or seven words) and straightforward. Online headlines tend to be longer and use catchy language. Images, captions, and subheadlines are more common with print headlines than web headlines (Davis & Davis, 2009).

Web headlines usually appear as links that lead the reader to the actual article. Given the acceleration of media consumption, many readers simply want to know the basic information about an event. The headlines used with web publications give readers enough information to understand what is happening without reading the story.

How to create a headline

Writing headlines takes practice. You need to select words carefully and use strong writing in order to entice the audience to read the article.

Create the headline after you finish writing the article so that you have a complete understanding of the story. Focus on how you can communicate the main idea in a manner that will capture the reader’s attention. Also, focus on keywords and do not include articles such as a, an, and the. Use present-tense verbs for headlines about events in the past or present. For events in the future, use the infinitive form of the verb: for example, “Local store to open a new location.”

Unlike the traditional summary lead, feature leads can be several sentences long, and the writer may not immediately reveal the story’s main idea. The most common types used in feature articles are anecdotal leads and descriptive leads. An anecdotal lead unfolds slowly. It lures the reader in with a descriptive narrative that focuses on a specific minor aspect of the story that leads to the overall topic. The following is an example of an anecdotal lead:

Sharon Jackson was sitting at the table reading an old magazine when the phone rang. It was a reporter asking to set up an interview to discuss a social media controversy involving Jackson and another young woman.“Sorry,” she said. “I’ve already spoken to several reporters about the incident and do not wish to make any further comments.”

Notice that the lead unfolds more slowly than a traditional lead and centers on a particular aspect of the larger story. The nut graph, or a paragraph that reveals the importance of the minor story and how it fits into the broader story, would come after the lead. There will be more on the nut graph later in this chapter.

Descriptive leads begin the article by describing a person, place, or event in vivid detail. They focus on setting the scene for the piece and use language that taps into the five senses in order to paint a picture for the reader. This type of lead can be used for both traditional news and feature stories. The following is an example of a descriptive lead:

Thousands dressed in scarlet and gray T-shirts eagerly shuffled into the football stadium as the university fight song blared.

For each article below, identify whether it uses a descriptive or anecdotal lead:

The content in a feature article isn’t necessarily presented as an inverted pyramid; instead, the organization may depend on the writer’s style and the story angle. Nevertheless, all of the information in a feature article should be presented in a logical and coherent fashion that allows the reader to easily follow the narrative.

As previously stated, the nut graph follows the lead. This paragraph connects the lead to the overall story and conveys the story’s significance to the readers (Scanlan, 2003).

The nut graph comes from a commonly used formula for writing features, known as the Wall Street Journal (WSJ) formula (International Center for Journalists, 2016). The formula was named after the well-known and respected publication, which created the term “nut graph” and mastered feature news writing (Rich, 2016).

The formula consists of beginning the story with feature-style leads to grabbing the reader’s attention, followed by the nut graph (Scanlan, 2003). After this comes to a longer body of the story that provides the usual background, facts, quotes, and so on. The formula then specifies a return to the opening focus at the end of the story using another descriptive passage or anecdote, also known as the “circle kicker” (Rich, 2016). This could be, for example, an update on what eventually happened to the main character or how the event or issue turned out. This blog post provides a detailed example of the WSJ formula.

Literary Devices

Feature writers use a particular style of writing to convey the story’s message. The use of literary devices helps in this task. These devices include similes and metaphors, onomatopoeia (use of words that mimic a sound), imagery (figurative language), climax, and more. Here are a few examples of onomatopoeia and imagery:

Onomatopoeia: The tires screeched against the concrete as she hit the pedal.

Imagery (example modified from Butte College, 2016): The apartment smelled of old cooking odors, cabbage, and mildew; . . . a haze of dusty sunlight peeked from the one cobwebbed, gritty window.

Click here for more information on literary devices, including specific examples.

Descriptive Writing

A good feature writer uses plot devices and dialogues that help move the story forward while focusing on the central theme and providing supporting information through descriptive language and specific examples. You want to show readers what’s happening, not simply tell them. They should be able to visualize the characters, places, and events highlighted in the feature piece.

Show Versus Tell

Tell: Friends describe Amariah as a generous and vibrant person who was involved in several nonprofit organizations.

Show: Tracey proudly recalls her friend’s generosity. “Amariah is usually the first person to arrive at a volunteer event and the last to leave. She spends four hours every Saturday morning volunteering at the mentoring center. It’s rare to not catch her laughing, flashing her perfect smile. She’s just a burst of positive energy.”

It’s often tempting to end a feature piece with a summary conclusion. Instead, use an anecdote, passage, or compelling quote that will leave a lasting impression on your readers.

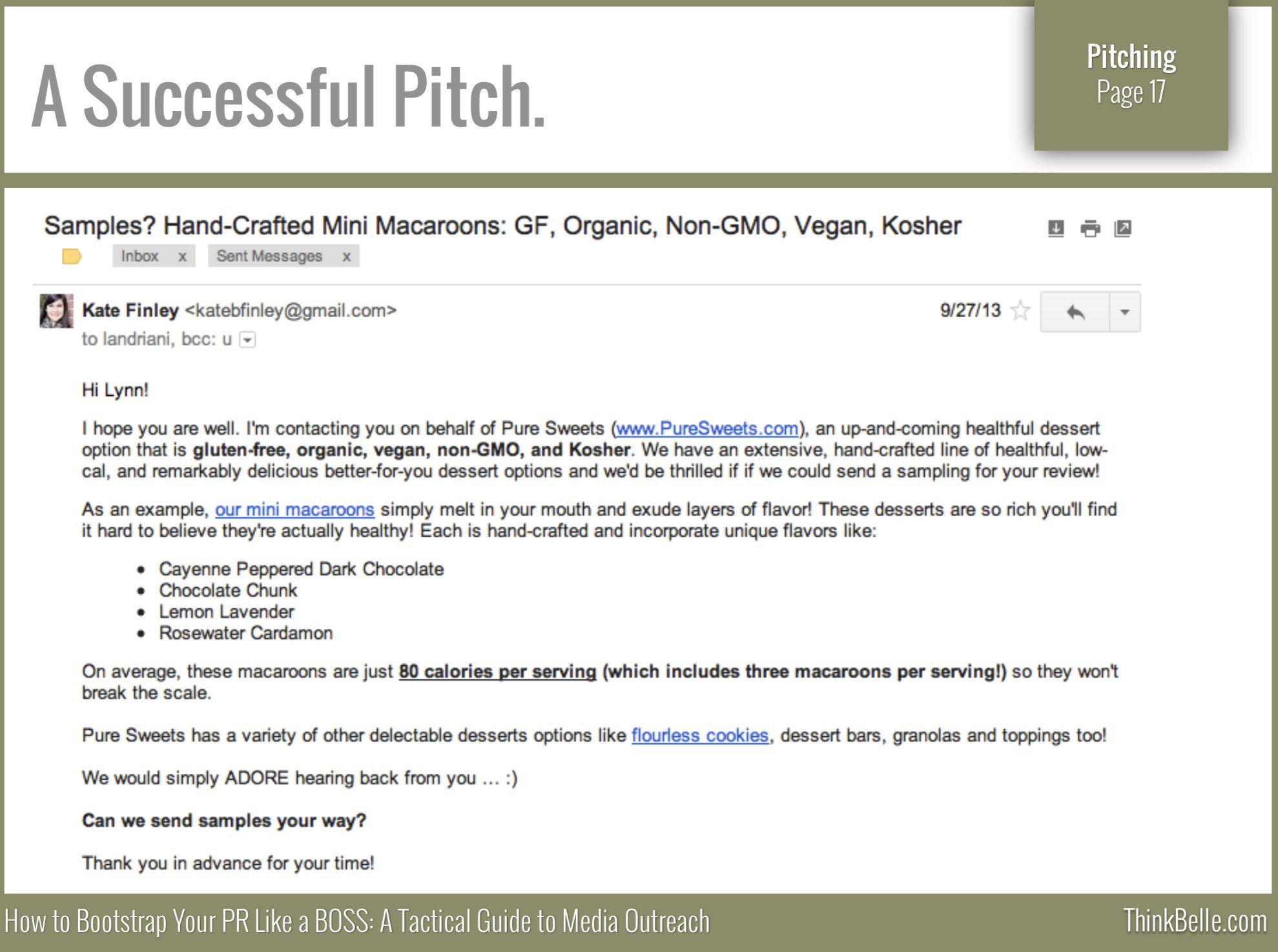

As with any professional relationship, there are do’s and don’ts to be aware of when developing relationships with journalists. Take the time to research reporters or bloggers to identify those who will help you achieve your organization’s publicity goals. Once you’ve found an appropriate journalist or blogger, think carefully about how you plan to pitch your story to the individual. Avoid gimmicky or hyped-up press releases; they may catch the reporter’s attention, but for the wrong reason. Also avoid jarring language such as “urgent,” “must read,” or “extremely important,” even if you need to secure media coverage quickly.

In general, developing a rapport with journalists takes time, strategy, skill, and practice. For more information on what you can do to develop a good working relationship with the media, take a look at this video with Alissa Widman Neese, a journalist at the Columbus Dispatch. She discusses her experiences working with public relations professionals and some of the factors that made them positive.

A Journalist’s Perspective on Pitching with Alissa Widman Neese

Simply contacting the media will not guarantee coverage for your client. You have to persuade the journalist that your story idea is newsworthy. Public relations professionals typically pitch to reporters, editors, bloggers, and social media influencers. Pitches can take place via email, phone calls, and increasingly through Twitter. The channel you choose for your pitch depends upon the intended individual’s preference.

Pitching is a skill that requires creative thinking, persuasive communication skills, and knowing how your story idea benefits the reporter and the audience. Your pitching skills can improve with time and practice. You will feel more confident reaching out to reporters if you write pitches regularly.

Before Pitching

Before you send an email pitch or call a reporter, it is important to have a solid understanding of your key audience. Carefully examine the interests, preferences, media consumption behaviors, and key demographic information associated with that group. Then you can more accurately select which media outlet will help reach the target audience.

Go where your audience is located. For example, as you conduct research about your target audience, you might learn that members read blog posts more than news articles. Therefore, reaching out to bloggers could be more beneficial than targeting news reporters. Place your message or story in media outlets that your intended audience frequently visits or reads.

One of the most common complaints from journalists about public relations pitches involves the use of mass emails. Generic pitches sent out to anyone and everyone come across to reporters and bloggers as careless and can compromise your credibility among media professionals. Remember, reporters are going to look at how your story will appeal to their specific readers; therefore, your pitch needs to be strategic. Failure to keep this in mind may result in a rejected pitch or no response at all.

Before you pitch to a particular media outlet, be sure to research which specific writer within the organization can help you target your audience. Each reporter covers a different topic, or “beat.” Reading some of a reporter’s previous stories will give you an indication of whether he or she is the right person to cover your story. Let’s say your client is a restaurant that wants to publicize the opening of a new location. A reporter who covers food topics and brands, lifestyle topics, or the restaurant industry would be the most logical choice to write your story.

Writing the Pitch

Now that you’ve done your homework on the audience, media outlet, and specific writer, pay close attention to how you craft your pitch message.

The subject line is especially important if you’re using email. It needs to be creative enough to catch the attention of the writer; however, avoid exaggerated phrases or visual gimmicks such as all capital letters. Do not use generic headlines such as “Story Idea” or “Cool Upcoming Event.” Try to create a headline similar to one the journalist might use in writing the story.

Next, address the reporter or blogger by name and begin the body of the pitch. State why you’re writing, and provide some information about yourself and the company or client you represent. Next, summarize the lead of the story. Writing in this manner resonates with some reporters, as it is the style they are accustomed to. You also can start the email with a catchy line that will hook the journalist, but be careful not to overdo this. Reporters and editors do not like flowery or gimmicky language because it sounds more like a hard sales pitch than a public relations pitch. Continue with the pitch by providing important details about the story and talking about why it would be interesting to the media outlet’s audience. Doing this indicates that the story has news value, which is very important in pitching. Toward the end of the email pitch, state when you would like a response, indicate when you plan to follow up if necessary, and offer specific help. Be sure to thank the reporter or blogger for his or her time.

Don’t feel discouraged if the person does not respond immediately. Journalists are extremely busy, and sometimes they simply overlook emails. If necessary, send a reminder email by the follow-up date you mentioned in the first communication. This date depends on when the story should hit the press. If you pitched a story that needs to be published relatively quickly, you may want to follow up no later than two days after sending the initial pitch. If there’s more flexibility in the desired publication date, you may indicate that you will follow up within a week. If the person still does not respond to your pitch, move on to another outlet, reporter, or blogger who can help you accomplish your publicity goals. It is important to also consider timing; for example, do not make a follow-up call at 4:55 P.M. on a Friday when the journalist may be getting ready to head home for the weekend.

Grammar, punctuation, tone, and spelling are important when writing email pitches. Some journalists have admitted to not responding to a pitch that contains grammatical and spelling errors. Reread your message several times to check for errors. Here are more articles that discuss media relations, proper etiquette, and tips on gaining media exposure:

The press release or news release is one of the most common communication materials written by public relations professionals. Press releases are sent to outlets such as newspapers, broadcast stations, and magazines to deliver a strategic message from an organization that the media ideally will publish or broadcast. The primary audience for the press release is reporters and editors, although some organizations publish press releases on their own websites for audiences to view. This may be done due to shrinking newsroom staffs and insufficient resources to develop original content.

Journalists use press releases as a reporting tool, relying on them to provide essential information and therefore make it easier for them to cover a variety of events. With the increase in media channels and demand for social content, some view press releases as an uninteresting way to distribute information and connect with audiences (Galant, 2014). Others see them as a concise and straightforward way to communicate to key publics.

Although the emergence of digital media has challenged public relations professionals to think of nontraditional ways to garner publicity, the use of press releases is still widespread in the profession. Therefore, public relations practitioners should know how to write an effective press release.

Traditionally, press releases use the inverted pyramid style, which makes it easy for journalists and editors to receive the most essential information first. This means the news hook should be revealed in the headline and lead of the release. Journalists will not take your press release seriously if the content is not newsworthy and it is not written in an accepted style, such as AP style. Make sure that the press release contains attributed information with proper sources and is error-free.

Before writing the release, ask yourself the following questions:

- Is the announcement or event newsworthy? Does it appeal to the media outlet’s audience? Some announcements do not warrant a press release and can simply be posted on the company website.

- What is the key message? What should the reader take away?

- Who is the target audience for the release? Although you’re writing the release for the media, you need to keep in mind the kind of readers or listeners you hope to attract.

In this video, Gina Bericchia, senior media strategist at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, discusses proper press release writing.

Discussion on Press Release Writing with Gina Bericchia

This article from Ragan Communications discusses when to send a press release to the media.

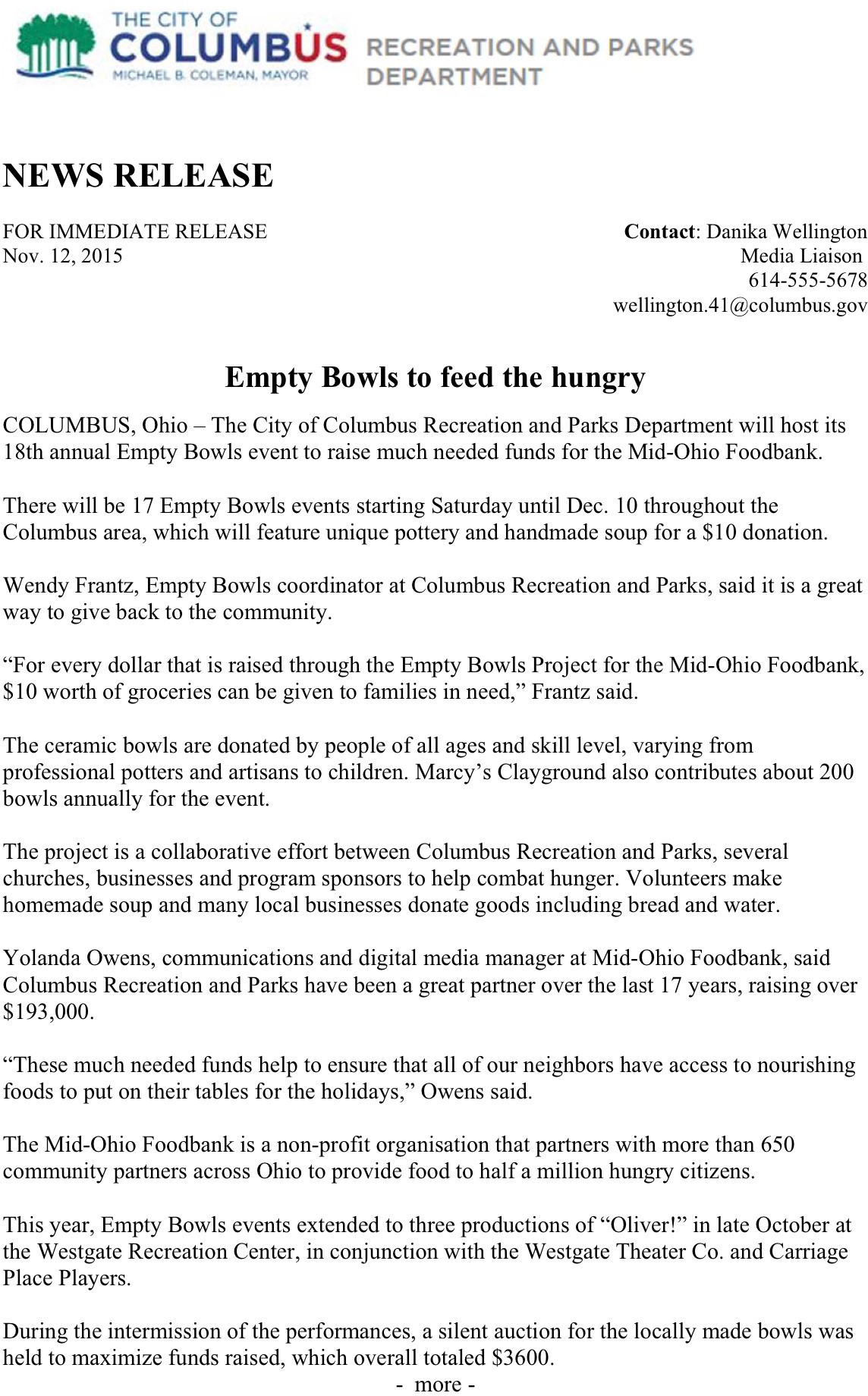

Press Release Structure and Format

The release should be written on the company letterhead, with the words “Press Release” or “News Release” at the top left corner of the page. Below this, indicate when the information is available for publication. The term “immediate release” means the information is ready to publish and can be used by journalists as soon as they receive it. Occasionally, you might want more time to gather other information, or would prefer that the journalist publish the announcement at a later date. In this case, use the term “under embargo until” followed by the embargo date, which is when you will allow the journalist to publish the information. Put the press release date below the “immediate release” or “under embargo until” statement. Always include contact information for the journalist’s reference, preferably at the top right corner.

Write the body of the press release using news writing techniques and style. Be sure to include a headline; you also may include a subheadline. Provide a dateline, followed by the summary lead. Here’s an example:

Long Description

NEWS RELEASE Contact: Danika Wellington FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Nov. 12,2015 Media Liaison 614-555-5678 wellington.41 @columbus.gov

Empty Bowls to feed the hungry. COLUMBUS, Ohio – The City of Columbus Recreation and Parks Department will host its 18th annual Empty Bowls event to raise much needed funds for the Mid-Ohio Foodbank. There will be 17 Empty Bowls events starting Saturday until Dec. 10 throughout the Columbus area, which will feature unique pottery and handmade soup for a $10 donation. Wendy Frantz, Empty Bowls coordinator at Columbus Recreation and Parks, said it is a great way to give back to the community. “For every dollar that is raised through the Empty Bowls Project for the Mid-Ohio Foodbank, $10 worth of groceries can be given to families in need,” Frantz said. The ceramic bowls are donated by people of all ages and skill levels, varying from professional potters and artisans to children. Marcy’s Clay ground also contributes about 200 bowls annually for the event. The project is a collaborative effort between Columbus Recreation and Parks, several churches, businesses and program sponsors to help combat hunger. Volunteers make homemade soup and many local businesses donate goods including bread and water. Yolanda Owens, communications and digital media manager at Mid-Ohio Foodbank, said Columbus Recreation and Parks have been a great partner over the last 17 years, raising over $193,000. “These much needed funds help to ensure that all of our neighbors have access to nourishing foods to put on their tables for the holidays,” Owens said. The Mid-Ohio Foodbank is a non-profit organization that partners with more than 650 community partners across Ohio to provide food to half a million hungry citizens. This year, Empty Bowls events extended to three productions of “Oliver!” in late October at the Westgate Recreation Center, in conjunction with the Westgate Theater Co. and Carriage Place Players. During the intermission of the performances, a silent auction for the locally made bowls was held to maximize funds raised, which overall totaled $3600.

Be sure to use the inverted pyramid to organize the information throughout the press release. Include at least two quotes, one from the company or organization and another from a third party (example: customer, volunteer, a current or former attendee at the event). After you’ve finished with the body, put the boilerplate at the end of the document. The boilerplate provides information about the company or organization, similar to the “About Us” section that you might find on a company website.

The press release should be as concise as possible and ideally no longer than one page. If it exceeds one page, do not split paragraphs. Instead, put the word “more” at the bottom center of the first page to indicate to the reader that there is more content on a second page. Include three pound signs (###) or “-30-” at the bottom of the press release to indicate the end.

These sample press releases contain some of the basic elements:

Further Reading

This article from Ragan’s PR Daily provides suggestions to improve your public relations writing.

An additional article from Ragan’s PR Daily explains common press release mistakes.

Press kits or media kits are packages or website pages that contain promotional materials and resources for editors and reporters. The purpose is to provide detailed information about a company in one location. Although a press kit delivers more information than a press release, the overall goal is similar: to secure publicity for a company or client.

Major events or stories that require more information than is typically included in a press release warrant a press kit. Examples include a company merger, the launch of a new product, a rebranding campaign, or a major change in organizational leadership. Press kits can be hard copy or digital. Hard-copy press kits use folders with the company logo, whereas digital press kits use a website page or are sent in a zip file via email.

The following materials are found in a press kit:

- Backgrounder

- Press release

- Fact sheet

- Publicity photos or list of photo opportunities

- Media alerts

Click here for information on how to assemble a press kit.

Backgrounder

A backgrounder contains the history of a company and the biographies of key executives. The purpose is to supplement the press release and explain the company’s story or event, products, services, and milestones. It is in paragraph format and relatively brief (one to two pages). Click here for a sample corporate backgrounder from GainSpan, a semiconductor company (creator: Javed Mohammed).

Fact Sheet

A fact sheet provides a summary of an event, product, service, or person by focusing only on essential information or key characteristics. It is more concise than a backgrounder and serves as a quick reference for reporters. However, the fact sheet is not meant for publication. The headings of a fact sheet vary; the creator of the document chooses how to categorize major information. The most common type of fact sheet is the organizational profile, which gives basic information about an organization. This includes descriptions of products or services, annual revenues, markets served, and the number of employees.

The standard fact sheet contains a company letterhead and contact information. The body is single-spaced, with an extra space between paragraphs and subheadings. Although the fact sheet is typically one page, put the word “-more-” at the bottom of the first page to indicate additional pages. Similar to the press release format, include three number signs or “-30-” at the bottom of the document to indicate the end. To make it easy to read, group similar information together and include bulleted items if appropriate.

Click here or an example of a fact sheet. Keep in mind that the subheadings/categories used in this example may not be used in another one. Writers have some flexibility in the categories they choose in a fact sheet.

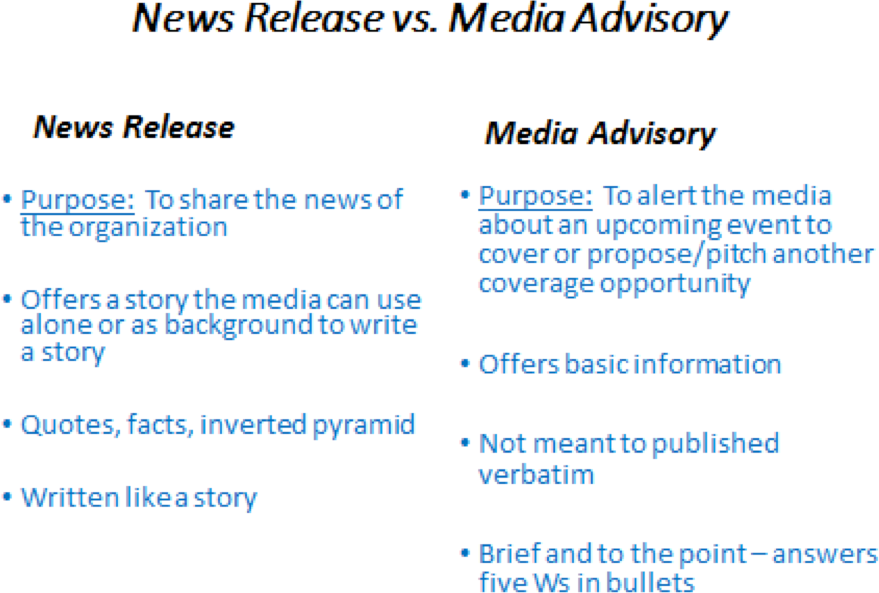

Media Alert

There are times when announcements do not require the distribution of a press release, but rather a concise notice to the media. This is called a media alert or advisory. Media alerts are memos to reporters about an interview opportunity, press conference, or upcoming event. They use the 5Ws and H format to quickly deliver information.

The illustration below explains the key differences between a press release and a media advisory:

Long Description

News Release: Purpose: to share the news of the organization. It offers a story the media can use alone or as a background to write a story. Quotes, facts, inverted pyramid. Written like a story; while Media Advisory’s purpose is to alert the media about an upcoming event to cover or propose or pitch another coverage opportunity. It offers basic information. Not meant to be published verbatim. Brief and to the point – answers five W’s in bullets.

Here are some examples of media alerts:

Before they begin the design process, advertising professionals work on explaining and outlining the advertising plan in a creative brief. This is a document for the creative team, the advertising director, and the client that gives a clear objective for the copied material and explains the overall concept of the campaign. The creative brief is like a game plan—without it, the advertisement may not be successful. You do not have to use a particular writing style, such as AP style when completing the creative brief. However, grammar, spelling, punctuation, and concise writing are still important. Here are several broad categories to consider when completing the creative brief.

Key Consumer Insight

The key consumer insight demonstrates a clear understanding of the consumer’s general behaviors, beliefs, and attitudes as they relate to the message topic. It also considers general opinions and thoughts about the subject matter. Let’s say you’re developing a creative brief for a cookie brand. Market research and careful audience analysis can reveal key insights into consumer behaviors, such as the fact that many consumers believe that so-called healthy cookies do not taste as good as their high-calorie, sugar-filled counterparts. This knowledge will help you as you design your advertisement.

Advertising Problem

The phrase “advertising problem” does not refer to addressing a problem within the advertisement itself, or challenges in advertising to the key audience. The term refers to the product’s biggest consumer-related stumbling block. In the cookie example above, the advertising problem is that consumers face a choice between buying great-tasting cookies that are loaded with calories and sugar and buying ones that are low in sugar and calories but don’t taste as good. The consumer insight can inform or help you to come up with the advertising problem. The advertising strategy should address a consumer need or consumer-related problem. Without this, the advertisement will appear pointless.

Advertising Objective

The advertising objective explains the intended effects of the promotion on the target audience and clearly articulates the overall goal. The goal is not simply to persuade the audience. Think about how you want the audience to feel or believe about the featured product or service. Or, what do you want them to do in response to seeing the advertisement? An example of the objective for the cookie advertisement might be to convince cookie lovers that the featured product is a healthy option that doesn’t compromise rich, fulfilling taste.

Target Consumer

The target consumers are people you specifically want to communicate the message to. In order to fully understand the audience, consider their psychographics, or the analysis of their lifestyles and interests. Also include information about demographics, as this factor influences the audience’s day-to-day experiences. Clarify why you’ve chosen this particular audience. Why would these people be attracted to the featured product or service? How would it help the organization achieve its goals? What are the benefits of targeting this particular group? Answering these questions will help justify the selection of the target audience.

Competition

In this section of the creative brief, perform a complete assessment of the competition that considers strengths and weaknesses. Specifically, examine the competitor’s history, products, services, brand, and target audiences. Analyzing key competitors will help you articulate your company’s or product’s marketplace niche, which is very important. You need to establish how your product or company stand out from similar products or companies.

Key Consumer Benefit

The key consumer benefit describes what the consumer would gain from using the advertised product or service. This section also discusses how the product or service solves the advertising problem laid out earlier in the creative brief. Narratives, testimonials, and sometimes research findings can be used as support in the actual advertisement, which helps enhance its persuasiveness.

Support

The support section explains the validity of the proposed advertising plan. It makes a case for why the campaign will motivate the audience or make them believe that the claims are true. This is particularly important because, in order to secure the advertising account, you need to convince your client or high-level executives that the plan will work. Include evidence from third-party sources such as external research studies or polls. Also, include feedback from focus groups to persuade the client that the advertising plan is effective.

Other Categories to Consider

Some creative briefs might include a section called tonality. This explains the desired feel or attitude of the advertising campaign, such as “hip,” “classy,” “fun,” “flashy,” or “modern.” You could also include a description of the advertisement’s visual elements, or the creative mandatories. This section should provide a detailed explanation of the images, slogan, logo, and other visual factors so that the client can imagine how the advertisement will look. The creative team usually presents a sample advertisement to the client in the pitch presentation.

After completing the creative brief and receiving approval from the client, it is now time to develop the advertisement. A large part of this process involves copywriting. Copywriting puts together the headlines, subheadlines, and images included in the advertisement. It uses persuasive communication to influence the target audience. It also helps to create the advertisement’s call to action, logo, and slogan.

The AIDA model is a popular framework used in designing advertising copy. The acronym stands for Attention, Interest, Desire, and Action. Good advertising copy should effectively grab the audience’s attention through words and/or imagery. This can be challenging. Because consumers may see thousands of advertisements daily, capturing their attention needs to be informed by strategy.

After getting the audience’s attention, the copy should maintain the focus of the consumer by generating interest. This involves creating messages that are relevant to the target audience (Altstiel and Grow, 2016). The AIDA model states that the copy should provoke a desire for the advertised product or service. When the desire is instilled, the copy should then motivate the audience to act or perform the call to action in the advertisement. This could be buying the product, visiting the organization’s social media page, volunteering, or attending an event. The call to action should be memorable. For further information on the AIDA model, click on this article.

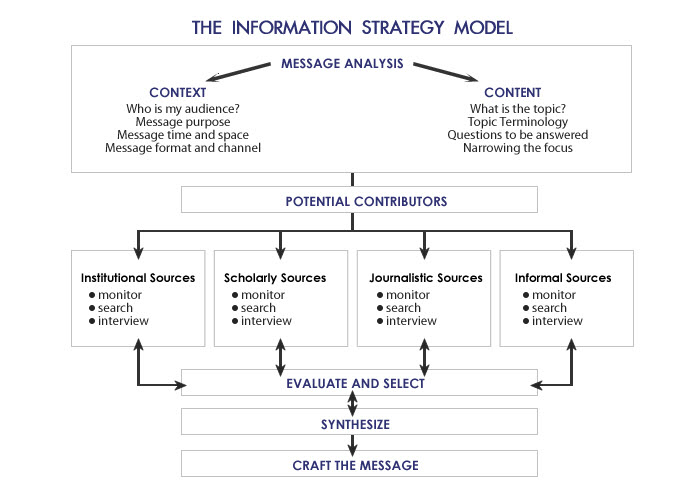

Over the course of the semester, we’ve examined the steps a communications professional must take when trying to tackle a new information task or message assignment.

Long Description

Step 1: Message Analysis: arrows point to Context (Who is my audience? Message purpose. Message time and space. Message format and channel.) and Content (What is the topic? Topic Terminology. Questions to be answered. Narrowing the focus.). Step 2: Potential Contributors: 4 arrows point to: #1 Institutional Sources (monitor, search, interview), #2 Scholarly Sources (monitor, search, interview) #3 Journalistic Sources (monitor, search, interview) #4 Informal Sources (monitor, search, interview). Each of these 4 has 2-way arrows pointing to Evaluate and Select which has a 2-way arrow pointing to Synthesize which then has an arrow pointing to Craft the Message.

These steps, by way of review, are:

- clarify the parameters of the message assignment.

- identify potential audiences.

- generate ideas and bring focus to the topic.

- understand the variety of potential contributors of information.

- appreciate the ethical and legal considerations required.

These first steps of the process will help you generate a set of questions or information “tasks” that you will need to perform in order to create the required communication message. Thinking about the potential contributors that could provide information to complete those tasks or answer the questions will get you started on the information strategy process. Knowing the ethical expectations and how to craft a message that meets legal standards will help guide you as you find and select information to use.

We’ve also discussed the key skills researchers must hone to be efficient and strategic in their information strategy tasks. These skills are:

- Searching: understanding how and where to locate both traditional repositories and databases of material and more esoteric or specialized resources, and constructing an effective search “equation” with appropriate keywords and utilizing search fields.

- Interviewing: finding and “vetting” people from a variety of contributor types who might have information, insights, or perspectives on whatever you are searching and developing the techniques to best engage and elicit helpful responses from them.

- Evaluating: knowing how to detect bias, misinformation, or unsubstantiated information you might find through searching or interviewing.

- Managing and Synthesizing: developing techniques for keeping track of the information you locate, methods for synthesizing key points or ideas to generate new insights and criteria for selecting (or discarding) the information you find.

Finally, we’ve discussed the forms in which information appears. We’ve looked at the tools, techniques and special requirements for understanding and using information from:

- data and statistics

- polls and surveys

- public records

- periodical publications

Now it is time to apply all of these skills and use the suite of resources for specific kinds of information requirements. Here’s how to apply all of these skills and resources. The following scenarios will step through the thinking process and track the information-seeking path.

An information strategy is used throughout the message generation process. Here are the various stages at which communication researchers will need to locate information to complete the required tasks:

- Initial idea generation or project focusing

- Understanding the intended audience / who they are, what they do, where they are, how to reach them

- Understanding an unfamiliar topic

- Finding information from various types of contributors using different information gathering skills

- Understanding what the information means and how to organize and synthesize it for your message task

In this lesson we will work through several specific communication task scenarios and detail the thought processes and research strategy used when:

- analyzing the message needs

- clarifying the audience to address

- generating ideas and focusing on angles of a topic

- finding information on the topic / angle from a variety of types of contributors

- synthesizing and selecting material that was found

Freelance Magazine Scenario: You are a freelance reporter and you’ve been interested in the use of drones, particularly as the market is growing for non-combat use of “unmanned aerial vehicles.” You have a good contact at the Atlantic Monthly magazine and think you might be able to pitch a story to them.

Your task: what should you pitch, and how would you research the topic?

You’ve identified the Atlantic as the magazine you want to target.

- How long are Atlantic articles?

- How much are freelancers paid?

- How do I submit a proposal?

- To whom should I submit a proposal?

You need to learn about both the “gatekeeper” audience (the editor to whom you want to pitch your story) and the magazine’s target audience (the main concern of the editor.) Answering these questions will help clarify the orientation of the article you will pitch.

Questions to clarify audience:

- Which editor would actually read the pitch and decide? What can I learn about them?

Sometimes it is hard to know when the submission just goes to a general “pitch” box. But you can find the names by going to the magazine website. Find on the homepage where the key personnel is listed (hint: in this case, it is referred to as the Masthead.) Links are provided to the editors’ pages; in some cases, they have a little biographical information. If they don’t, it is worth checking on LinkedIn or Facebook to get a sense of their interests through posting (and it’s a good strategy to “like” or “connect” with them – people like to help out people who like them.)

- Who is the audience for the magazine? What would they be interested in? Are they highly educated?

A magazine’s media kit is compiled to provide advertisers and media buyer information about the audience it would reach if they placed an ad in that magazine. Every magazine site will have a button called “media kit” or “advertise” that will give valuable demographic and psychographic information about the audience for that publication. Here is The Atlantic’s media kit.

Your broad topic of interest is “drones” – but what angle on this should you take? Given your knowledge of the Atlantic’s audience, how do you start to zero in on potential ways to focus the topic?

Questions to clarify topic focus:

- What, if anything, has the Atlantic already written about drones?

Search the Atlantic’s website. Scanning through the articles retrieved (what is a good search strategy?) will give you some ideas of things they have covered – and help you find some different angles.

- What are some of the angles on the topic of drones that others are writing about?

Do a quick check on Google News – scanning the headlines might give you insights on a new angle. And you’d want to stay up to speed on the topic, so set several Google Alerts on different aspects of the topic (drones and legislation, drones and public safety, drones and shopping)

- What are people saying about drones? What are their issues or concerns?

Social media sites are a great way to see new and emerging topics of discussion or concern. Go to Facebook and see if there is an interest group – and who is talking about it. Follow a Twitter hashtag (like #drone or #dronesforgood)

After brainstorming angles and understanding the interests of the Atlantic audience, you decide the use of drones for delivery services would be an interesting focus. As commercial firms from Amazon to local breweries and drug stores explore drone delivery, the regulatory or safety concerns this raises would be a great topic for Atlantic readers.

Now you need information. You develop a set of questions that could be answered with information from a variety of potential contributors. There are many ways to do this kind of brainstorming and if you have a very specific question, thinking through what kind of agency or organization would be likely to have information or data or expertise on that specific question is the logical first step.

For example, if you want to know what the outlook is for the drone industry, you might want to find a public sector agency that generates industry outlooks and see what they have published. Check the government search engine USA.gov for drone manufacturing and you get a report published by the Congressional Research Service on UAS manufacturing trends.

But if your specific question is “how many accidents have there been from the use of drones?” it would be logical to think about which agency is likely to track that sort of information. At the national level, it would be the Federal Aviation Administration. You do a search on drone accidents at faa.gov and the second item looks perfect: A Summary of Unmanned Aircraft Accident / Incident Data. Sadly, on further examination, you see that it doesn’t pass the recency or relevance tests of evidence. But you have identified the likely agency for this kind of information – so it might be time to pick up the phone and make a call to see if you can locate someone who knows about those types of records and ask for the most recent version of the report.

At the beginning stages of the information strategy, sometimes you are better off with imagining the kinds of information that different contributors could offer – and the sort of questions they can answer. Here’s how that brainstorming might look for this particular topic:

Public Sector Institutions: government agencies could provide answers to questions about drones and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) related to:

- Economy: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Department of Commerce: census of business and manufacturing, specific financial information about companies in the drone business, the employment outlook for the industry

- Safety: Federal Aviation Administration, Department of Transportation, Homeland Security: concerns about usage, creative uses of drones (for traffic regulation or monitoring road conditions)

- Regulation: Department of Justice, State Legislatures: laws regulating use can be handed down at different levels of government

- Technology: National Technical Information Service: technical reports

A good strategy for finding public sector sources that might have information to gather or experts to interview is to look through the directory of government agencies.

Private-Sector Institutions: You’ve decided your angle is the regulation of drones for commercial use. Clearly, you would want to identify some commercial enterprises that would be affected. Researching the background of this angle provides stories about a drug store in San Francisco, a brewery in Minnesota, and the mega-online store Amazon as having used, or want to use, drones to deliver products. Going to the corporate sites for QuiQui, Lakemaid Beer, and Amazon would provide answers to questions about their use of drones – and more importantly, the names of people you might want to interview.

On the non-profit side, talking to people in advocacy groups or organizations with concerns about the use of commercial drones can help fill in questions about the different perspectives on the issue that should be considered. These are often good places to check for backgrounders or “white papers” on the topics of most interest to those associations.

Do a search in Google for drones and association – look at their websites to see issues they cover. For a more authoritative source on associations, check the Associations Unlimited database (found on the UMN library website.)

Scholarly: Conducting a search for scholarly articles in the Business Source Premier database using the search equation (“drone aircraft” OR “unmanned aerial vehicles”) NOT war, you locate a number of relevant articles. One that appeared in Computer Law and Security Review is titled “Drones: Regulatory challenges to an incipient industry,” and the abstract of the article sounds like it is a good fit for your needs. A challenge with using scholarly sources can be deciphering the specialist language they use in their writings. For journalists, it can be better to find sources to interview – scholars will speak more conversationally than they will write. In the Lesson on Interviewing we talked about sources for locating scholars to interview. In this case, you would read the article and then contact the author, David Wright, for an interview.

Journalistic: News articles are essential sources for other journalists – not only to find out what has been covered but also to see the types of sources that have been used. You’ll want to search one of the news archives services such as Google News (if you only want recent stories) or LexisNexis for broader coverage. In this case, however, you also find that journalists themselves are interesting sources of information because many of them want to use drones in their news work. So, journalistic sources are not only fodder for background and places to cull for good sources to find, but they are also sources themselves. You might want to contact the Professional Society of Drone Journalists.

Informal Sources: If you are writing about how drones for commercial or non-military use are being regulated, you’d want to find some “just folks” to represent the impact of regulation. You’ll need to brainstorm the kinds of people you would want to hear from: people who use drones for fun, those concerned about drones flying over their neighborhood, people who have been injured by a drone, people who can’t wait to have their latest purchase from Amazon dropped on their doorstep. Locating informal sources might mean finding specific people who have posted on social media sites (look for tweets or pages related to drones) or it might be posting a “call” for comment on these sites and seeing what kinds of response you get. Reading the comments on articles you found through journalistic sources might lead you to interesting informal sources to interview.

Search Tip: A term like “drone” has multiple related terms and different ways different disciplines will refer to the term. Take care when searching to try different versions (drone, UAV, UAS, Unmanned Aerial Vehicle…)

As you can see from this scenario, there are many steps and hundreds of information sources that could help with this message task. We are just scratching the surface of what you would actually need to do to prepare this type of story pitch to the editors of The Atlantic.

You work as a Communications Manager for the American Wind Energy Association (AWEA), the trade group that represents the country’s wind energy industry. An article appears in the Journal of Raptor Research that reports on the results of a study by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The study found that wind energy facilities have killed at least 85 golden and bald eagles between 1997 and 2012—and those eagle fatalities possibly may be much higher. The study also indicated that eagle deaths have increased dramatically in recent years as the nation has turned increasingly to wind farms as a source of renewable, low-pollution energy, with nearly 80 percent of the fatalities occurring between 2008 and 2012 alone.

Your Executive Director (ED) asks you to prepare the Association’s response to the questions and requests for comments that are certainly going to be pouring in as the results of the study start to gain public awareness. You need to get up to speed quickly on the topic of bird mortality due to wind energy facilities. Let’s look at how you would prepare to respond to this “crisis.”

Your discussion with the Executive Director would include seeking the answers to these questions:

- Does the ED want to issue a statement to the media on behalf of the AWEA?

- If yes, should that be in the form of a news release, a news conference, a streaming web conference, something else?

- Does the ED want to consider posting something on the AWEA’s website as part of the response?

- If yes, you need to determine “best practices” for how to do this effectively.

- Does the ED want to provide “talking points” to the industry members of the AWEA so they know how to respond if they get questions? How should those “talking points” be distributed most effectively?

- Similarly, should the AWEA communicate with other stakeholders with an interest in the work of the AWEA? What form would that take?

Once you clarify the types of messages and the communications strategy your ED wants you to pursue, you need to determine the audiences who will be targeted. This leads to another set of questions:

- Which media outlets should we target with our news releases/news conference/web conference messages? Are we trying to reach media organizations that produce news and information for the general public or for specialist audiences? Who are those specialist audiences?

- What will our industry members need to have in the “talking points” material we create for them? We need to anticipate their information needs since our mission is to help association members be effective advocates for the wind power industry as well as succeed in their individual business endeavors.

- Who are the other stakeholders we might target with our response? Our partner organizations and associations at the state and national level? Regulators at the state and national level who govern our industry? Bird enthusiasts, who oppose wind turbines? Environmentalists, who care about both renewable energy AND wildlife protection? Researchers inside and outside the government who study bird mortality and wind power?

- Once we know which stakeholder audiences we want to address, how can we best reach them with our messages?

Based on your discussions with the ED, you start to brainstorm some of the ways you might address the message task. Again, you identify some questions that can help you focus on the right angle.

- Aside from this one study, what do we know about bird mortality caused by wind energy facilities and who has studied the issue?

- What else kills birds and how does that compare with avian deaths from wind turbines?

- What are our member industries doing right now, if anything, to reduce bird mortality?

- How does energy production using other methods affect wildlife and how does that compare with wind energy production?

- What regulations are in place that our industry members must follow to protect birds? How are we doing with compliance?

Here is just a tiny sample of the information contributors you could tap and the information they might provide to help you focus your messages.

Public-sector Institutions

The Department of the Interior, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Wind Energy Guidelines provide detailed specifications for the way wind energy facilities must operate, including ways to reduce bird and other animal mortality. You might suggest posting a link to these guidelines on the AWEA’s website and include some narrative about the ways your members are complying with the regulations. You might also include this document and some of the data about compliance with your association members as part of their “talking points” material. This document could also be shared as part of a news conference or in any statement, your ED might issue to the media.

Private-sector Institutions

The National Academy of Sciences, a widely-respected, private-sector, non-profit organization, conducted a study about other causes of bird mortality in addition to those caused by the wind power industry. It appears from this study that bird mortality from other causes is much greater than bird deaths from wind power facilities. You might, once again, consider posting a link to this study on the AWEA’s website, compose some narrative that summarizes the findings of the study and make sure any public statements or “talking points” include the results. At the same time, you need to be sure that you don’t minimize the concern for bird mortality rates caused by wind power.

The National Wind Coordinating Collaborative is a private-sector, non-profit organization with partners from the wind industry, science and environmental organizations, and wildlife management agencies. They did a study of wind-wildlife interactions that summarized a huge amount of scientific and scholarly data and produced a fact sheet that outlines how the wind power industry and environmentalists are responding to the issue. This document would clearly be part of your information package.

Scholarly Sources

Conducting a search in Google Scholar using the search statement “bird mortality from wind energy” uncovers hundreds of scholarly studies done in the U.S. and around the world. The general consensus appears to say that there is a clear link between wind turbines and bird mortality, but there are lots of caveats in the findings.

One article in the scholarly journal Biological Conservation shows that bird mortality is greater with a type of wind turbine that is being phased out (lattice vs. monopole); that taller monopole turbines may pose more risk of raptor bird mortality than shorter monopole turbines because raptors fly at a higher elevation than songbirds (the usual victims of wind turbines), but that the blades on taller monopole turbines turn at a slower rate than the blades on shorter turbines so those risks may offset one another. Again, the data from studies such as this one would need to be summarized and included in any messages you generate.

Journalistic Sources

A search for journalistic coverage of this issue turns up thousands of news stories, including recent reports about offshore wind farms that pose fewer risks to birds than land-based turbines. Many news stories have been written about opposition to wind farms because of concerns about wildlife mortality, and there are state and local-level opposition as well as national-level concern. At the same time, editorials supporting wind energy as an alternative to the more harmful effects of other types of energy production have appeared in a number of newspapers in communities where the issue is of particular concern. This might suggest a list of news organizations you would want to target for your news releases since you know they have written about the issue and are open to a nuanced approach to the problem. You could also create a Google Alert on the topic so you would be notified whenever a new news story appears.

Informal Sources

You would want to monitor social media chatter about the most recent raptor mortality/wind power study and pay attention to those individuals and groups who seem to be most influential or have the largest followings. You could create a set of alerts on the most popular social media sites to be notified whenever there are new postings. You could then decide whether or not to respond based on the type of information in the postings or the likely impact of the messages. Additionally, you might suggest that the AWEA reach out to the most vocal individual opponents of wind energy (you would be able to generate a list of their names from the news stories you found) and incorporate their perspectives and concerns into your responses where appropriate.

The information you locate from a variety of contributors appears to show that there is definitely a problem with bird mortality and wind energy. At the same time, the wind power industry, private-sector institutions, public-sector institutions and scholars are working on ways to lessen the impact. Also, the potential danger to animal life from wind-power appears to pale in comparison to the danger posed to ALL life from other forms of energy generation (climate change due to rising CO2 levels, strip coal mining, fracking, oil pipeline construction through wildlife habitat, deepwater oil drilling, etc.).

You would want to be sure that your message strategy does not minimize the harm to birds, but also points out the efforts being taken by the industry to address the problems with newer technologies, additional precautions, changes in turbine sitings (offshore rather than on land), compliance with existing and emerging regulations and related initiatives.

The message strategy you might propose to your Executive Director would include recommendations to include these types of arguments, with plenty of links and references to the information and evidence you have located, in any public comments, website content, news releases, “talking points” documents, and related messages to address the immediate “crisis” and to address longer-term communication needs for the association.

Let’s say that you are working on a new business pitch for a possible advertising client. A new business pitch is the presentation and supporting documentation that an agency prepares to show to a prospective client in an effort to win that advertiser’s business.

The company whose advertising account you would like to win is United Airlines. The airline currently works with McGarryBowen advertising agency but since the merger with Continental Airlines, the company is considering other options for their advertising business.

The agency for which you work has not had a commercial airline account in the past so the first task in your preparation of the new business pitch is to get up to speed quickly on the passenger airline industry.

Questions to Pose:

- What is the overall economic health of the passenger/commercial airline industry?

- Who are the main players — the airline companies, the aircraft manufacturers, the regulators, the workers’ unions, the customers, the other stakeholders? What perspective or position does each player take on the industry?

- What does airline advertising look like? Who is advertising, where do the ads appear, what do the ads say, how effective are the ads?

- What restrictions and regulations, if any, govern advertising for this industry?

- Who comprises the largest and most lucrative group of airline travelers? In other words, who are airlines trying to reach with their ads?

Depending on the questions you need to answer, there is a vast array of potential sources of information. Following is a sampling of the contributors that would have relevant information and the kinds of information you could find.

Private-sector Institutional Sources:

- associations that are important for that industry (Airlines for America, Airline Passenger Experience Association, etc.)

- trade journals that discuss the most recent news and trends for that field (Aviation Week, etc.)

- financial records that detail the industry’s economic health from the company itself and from financial analysts who monitor the industry

- unions that represent the workers in that field (Airline Pilots Association, Association of Professional Flight Attendants, Transport Workers Union, etc.)

- demographic data that describe the customers for that industry’s products/services and the audiences for its ads

- syndicated research service reports about airline advertising

Public-sector Institutional Sources:

- court records that document the interactions the company and competitors in the industry have had with the U.S. justice system

- government records that document regulation of the industry (Federal Aviation Administration reports, Occupational Safety and Health Administration reports, etc.)

- government records that provide insight into the financial health of the industry (Bureau of Transportation Statistics reports)

- government records about consumer complaints about the industry (Aviation Consumer Protection agency reports which are housed in the U.S. Department of Transportation)

Scholarly Sources:

- experts who can speak authoritatively about the commercial airline industry

- experts who can speak about the effectiveness of advertising in that industry

Journalistic Sources:

- news operations that write about the industry or are published in towns where key companies in that industry operate

Informal Sources:

- social media pages where people talk about that industry and its products/services

Once you have a good understanding of the industry overall and the types of advertising that are typical for companies in that sector, you can start to search for specific information about United Airlines, the company for which you are preparing the new business pitch.

Again, you would identify a number of important questions to answer:

- How does United stack up against its competitors?

- Is the company financially sound?

- Does the company have a “unique selling proposition”?

- Who are United’s current customers and what do customers think about United?

- What do relevant workers’ groups think about United? (pilots, flight attendants, baggage handlers, air traffic controllers, aircraft manufacturers, etc.)

- What have United’s ads looked like in the past? To whom were they targeted? Where did the ads appear? Were they effective?

- How much has United spent on advertising in the past?

- Who should we propose that the airline target with their advertising? Business travelers, families, retirees, customers currently flying with other airlines or those who are traveling by other means, etc.?

A tiny sample of what you could find:

Private-sector Institutional Sources

- United’s own demographic data about customers

- United’s corporate information

- McGarryBowen’s advertising work for United

- Google Finance’s compilation of public-sector and private-sector data about the company

- Customer ratings for United produced by other organizations

- Syndicated research services reports about ad spending for United; this would tell you where United ads are currently appearing and would help you identify the audiences that are currently being targeted with the advertising

Public-sector Institutional Sources

- Securities and Exchange Commission annual reports for United

- Air Travel Consumer Reports from the U.S. Department of Transportation

Scholarly Sources

- scholars who have studied the company specifically

- scholarly studies about airline customer satisfaction that include United’s rankings

Journalistic Sources

- news stories about United in general

- business journalism reports about United as a company and an investment

- journalistic reports about United’s advertising

Informal Sources

- United’s social media accounts

- Other social media accounts that discuss United

- FlyerTalk and related blog posts about United

After reviewing the information you have found, you have learned that United is doing well financially but their customer satisfaction ratings are at the bottom of the heap and their current advertising campaign, which resurrected the 30-year-old slogan “Fly the Friendly Skies,” has been widely ridiculed as ineffective and downright misleading. Especially after the airline’s horrendous treatment of a passenger forcibly removed from a United flight in spring 2017, the company has a major PR problem. The company has simmering labor problems with its workforce (dissatisfied pilots, flight attendants, airplane mechanics, etc.) and a public image problem as a large, impersonal corporate behemoth after its merger with Continental.

Synthesizing all of this information, you would want to focus your brainstorming on a possible new advertising direction on a recommendation that the company repositions itself away from the claim about customer satisfaction because it cannot live up to that promise, especially after the fiascos of customer mistreatment in 2017. You and your advertising colleagues would want to identify other possible unique selling propositions on which the company could actually deliver (more non-stop routes to popular destinations, newer aircraft, more hubs, etc.) and be sure that any advertising claims could be clearly demonstrated and backed-up by the reality of the company’s performance.

Furthermore, you would want to examine in more detail the specifics of different audiences for the advertising — what appeals would work better with business customers vs. leisure travelers, etc.? If you find that the airline could have better results by targeting a subset of its customers with its new advertising rather than producing a general audience ad campaign, that is where you would focus your news business pitch.

The new business pitch to United’s decision-makers presents an opportunity for you and your advertising agency colleagues to demonstrate your command of the facts about the airline industry overall and the relative position of United Airlines within that industry. It also provides an opportunity for you to generate creative and effective suggestions for ways the company could improve its advertising and its public image.

All of the scenarios and examples we’ve provided here are intended to give you concrete insights into the way the information strategy process works for real-life communications message tasks. Internalizing the process will prepare you for the work you will do in the rest of your coursework and your career in journalism or strategic communication.

News Value and the Strategic Communication Professional

While watching or listening to a major media network, you may occasionally find yourself thinking, “Why is this story considered news?” Audiences assume that the role of the media is to provide them with the most important information about issues and events happening locally, nationally, and worldwide. Therefore, media outlets send an indirect message to audiences about a story’s perceived importance through the selection and how much time and exposure they give the story.

A story’s newsworthiness is largely determined by its news value, a standard that determines whether an event or situation is worth media attention. News value is referred to as “criteria used by media outlets to determine whether or not to cover a story and how much resources it should receive” (Kraft, 2015). Journalists and reporters are likely to spend their limited time and resources on a story that has many news values.