5.3. Structure of the Courts: The Dual Court and Federal Court System

Lore Rutz-Burri and Kate McLean

The Dual Court System

In the United States, each state has two complete, parallel court systems: the federal system, and the state’s own system. Thus, there are at least 51 legal systems in the country: the fifty created under state laws and the federal system created under federal law. Additionally, there are court systems in the U.S. Territories, and the military has a separate court system as well.

The state/federal court structure is sometimes referred to as the dual court system. State crimes, created by state legislatures, are prosecuted in state courts which are concerned primarily with applying state law. Federal crimes, created by Congress, are prosecuted in the federal courts which are concerned primarily with applying federal law. As discussed below, it is possible for a case to move from the state system to the federal system when a defendant challenges their conviction on direct appeal through a writ of certiorari, or when the defendant challenges the conditions of confinement through a writ of habeas corpus.

Dual Court System Structure

| Highest Appellate Court | U.S. Supreme Court (Justices) (Note: Court also has original/trial court jurisdiction in rare cases and will also review petitions for writ of certiorari from State Supreme Court cases). | State Supreme Court (Justices) |

| Intermediate Appellate Court | U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeals (Judges) | State Appellate Court (e.g., Pennsylvania Superior Court) (Judges) |

| Trial Courts of General Jurisdiction | U.S. District Courts (Judges) (Note: this court will review petitions for writs of habeas corpus from federal and state prisoners) | Name varies by state (e.g., Pennsylvania Courts of Commons Pleas) (Judges) |

| Trial Court of Limited Jurisdiction | U.S. Magistrate Courts (Magistrate Judges) | Magisterial Courts, Minor Courts (e.g., Pittsburgh Municipal Court) (Judges, Magistrates, Justices of the Peace) |

The Federal Court System

Article III of the U.S. Constitution established a Supreme Court of the United States and granted Congress discretion as to whether to adopt a lower court system. It states the “judicial Power of the United States shall be vested in one Supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.” Fearing that the state courts might be hostile to congressional legislation, Congress immediately created a lower federal court system in 1789. [1] The lower federal court system has been expanded over the years, such as when Congress created the separate appellate courts in 1891.

United States Supreme Court

The United States Supreme Court, located in Washington, D.C., is the highest appellate court in the federal judicial system. Nine justices sitting en banc, as one panel, together with their clerks and administrative staff, make up the Supreme Court. [View the biographies of the current U.S. Supreme Court Justices here. The Supreme Court’s decisions have the broadest impact of any court in the land, because they govern both the state and federal judicial system. The nine justices have the final word in determining what the U.S. Constitution permits and prohibits, and it is most influential when interpreting the U.S. Constitution. Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, Robert H. Jackson, stated in Brown v. Allen, 344 U.S. 433, 450 (1953), “We are not final because we are infallible, but we are infallible only because we are final.” Although it is commonly thought that the U.S. Supreme Court has the final say, this is not one hundred percent accurate. After the Court has read written appellate briefs and listened to oral arguments, it will “decide” the case. However, it frequently refers or sends back cases to the originating state’s supreme court, so they can determine what their own state constitution holds. Similarly, as long as the Court has interpreted a statute and not the constitution, Congress can always enact a new statute which modifies or nullifies the Court’s holding.

Writs of Certiorari and the Rule of Four

The Court has discretionary review over most cases brought from state supreme courts and federal appeals courts in a process called a petition for the writ of certiorari. Four justices must agree to accept and review a case – which happens in roughly 10% of the petitions filed. (This is known as the rule of four.) Once accepted, the Court schedules and hears oral arguments on the case, then delivers written opinions. Over the past ten years, approximately 8,000 petitions for writ of certiorari were filed annually. It is difficult to guess which cases the court will accept for review. However, a common reason the court assents to review a case is that the federal circuit courts have reached conflicting results on important issues presented in the case.

Original Jurisdiction of the Supreme Court: A Rarity

When the Court acts as a trial court it is said to have original jurisdiction, and it does so in a few important situations, such as when one state sues another state. The U.S. Constitution, Art. III, §2, sets forth the jurisdiction of the Court. It states,

“The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their Authority;-to all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls;-to all Cases of admiralty and maritime Jurisdiction;-to Controversies to which the United States shall be a Party;-to Controversies between two or more States;-between a State and Citizens of another State;-between Citizens of different States;-between Citizens of the same State claiming Lands under Grants of different States, and between a State, or the Citizens thereof, and foreign States, Citizens or Subjects.

In all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall be Party, the Supreme Court shall have original Jurisdiction. In all the other Cases before mentioned, the Supreme Court shall have appellate jurisdiction, both as to Law and Fact, with such Exceptions, and under such Regulations, as the Congress shall make.”

Original jurisdiction cases are rare for several reasons. First, the Constitution prohibits Congress from increasing the types of cases over which the Supreme Court has original jurisdiction. Second, parties in an original jurisdiction suit must get permission by petitioning the court to file a complaint in the Supreme Court. In fact, there is no right to have a case heard by the Supreme Court, even though it may be the only venue in which the case may be brought. The Supreme Court may deny petitions for it to exercise original jurisdiction because it finds that the dispute between the states is too trivial, or conversely, too broad, and complex. The Court does not need to explain why it refuses to take up an original jurisdiction case. Original jurisdiction cases are also rare because, except in suits or controversies between two states, the Court has increasingly permitted the lower federal courts to share its original jurisdiction.

United States Courts of Appeal

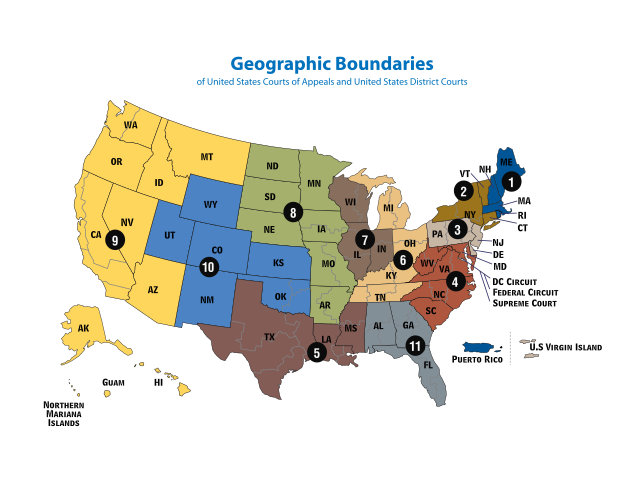

Ninety-four judicial districts comprise the 13 intermediate appellate courts in the federal system known as the U.S. Courts of Appeal, sometimes referred to as the federal circuit courts. These courts hear challenges to lower court decisions from the U.S. District Courts located within the circuit, as well as appeals from decisions of federal administrative agencies, such as the social security courts or bankruptcy courts. There are twelve circuits based on geographic locations and one federal circuit which has nationwide jurisdiction to hear appeals in specialized cases, such as those involving patent laws, and cases decided by the U.S. Court of International Trade and the U.S. Court of Federal Claims. The smallest circuit is the First Circuit, with six judgeships, and the largest court is the Ninth Circuit, with 29 judgeships. Appeals court panels consist of three judges. A full court will occasionally convene en banc and only after a party who has lost in front of the three-judge panel requests review. Because the Circuit Courts are appellate courts which review trial court records, they do not conduct trials and, thus, they do not use a jury.

The U.S. Courts of Appeal, like the U.S. Supreme Court, trace their existence to Article III of the U.S. Constitution. These courts are busy, and there have been efforts to both fill vacancies and increase the number of judgeships to help deal with the caseloads. For example, the Federal Judgeship Act of 2013 would have created five permanent and one temporary circuit court judgeships, in an attempt to keep up with increased case filings. However, the bill died in Congress. Fortunately, in recent years, fewer cases have been filed.

United States District Courts

The U.S. District Courts, also known as “Article III Courts”, are the main trial courts in the federal court system. Congress first created these U.S. District Courts in the Judiciary Act of 1789. Now, ninety-four U.S. District Courts, located in the states and four territories, handle prosecutions for violations of federal statutes. Each state has at least one district, and larger states have up to four districts. (Pennsylvania, for example, has three U.S. district courts). Each district court is described by reference to the state or geographical segment of the state in which it is located (for example, the U.S. Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania). The district courts have jurisdiction over all prosecutions brought under federal criminal law and all civil suits brought under federal statutes. A criminal trial in the district court is presided over by a judge who is appointed for life by the president with the consent of the Senate. Trials in these courts may be jury trials.

Although the U.S. District Courts are primarily trial courts, district court judges also exercise an appellate-type function in their review of petitions for writs of habeas corpus brought by state prisoners. Writs of habeas corpus are claims by state and federal prisoners who allege that the government is illegally confining them in violation of the federal constitution. The party who loses at the U.S. District Court can appeal the case to the court of appeals for the circuit in which the district court is located. These first appeals must be reviewed, and thus are referred to as appeals of right.

United States Magistrate Courts

U.S. Magistrate Courts are courts of limited jurisdiction in the federal court system, meaning that these legislatively-created courts do not have full judicial power. Congress first created the U.S. Magistrate Courts with the Federal Magistrate Act of 1968. Under the Act, federal magistrate judges assist district court judges by conducting pretrial proceedings, such as setting bail, issuing warrants, and conducting trials of federal misdemeanor crimes. There are more than five hundred Magistrate Judges who dispose of over one million matters each year.

U.S. Magistrate Courts are “Article I Courts” as they owe their existence to an act of Congress, not the Constitution. Unlike Article III judges who hold lifetime appointments, federal Magistrate Judges are appointed for eight-year terms.

Up for Debate: Should the Supreme Court Be Expanded?

After several politically-controversial rulings, many commentators and (largely Democratic) politicians have called for the expansion of the Supreme Court beyond its current nine justices. While this may strike some as short-sighted tampering with a sacred institution, the Supreme Court has been expanded, and shrunk, before – in fact, seven times in U.S. history! Such a topic is only imaginable because the U.S. Constitution says nothing about the required number of justices on the Court.

Consider how an expansion of the Court might effect the institution’s rulings, efficiency, and public legitimacy – or just read this debate from the Harvard Law and Policy Review. Would you support an expansion of the current Court’s roster – and why?

- (The Judiciary Act of 1789 (Ch. 20, 1 Stat 73) ↵