7.2. Retribution

David Carter and Kate McLean

Retribution

Retribution, arguably the oldest of the ideologies/philosophies of punishment, is the only one that is “backward-looking,” or focused on the past offense (as opposed to future offending). The primary goal of retribution is to ensure that punishments are proportionate to the seriousness of the crimes committed, regardless of the individual differences between offenders. Thus, retribution focuses on the past offense, rather than the offender. This can be phrased as “a balance of justice for past harm.” People committing the same crime should receive a punishment of the same type and duration that then balances out the crime that was committed. The term “backward-looking” means that the punishment does not address anything in the future, only for the past harm done.

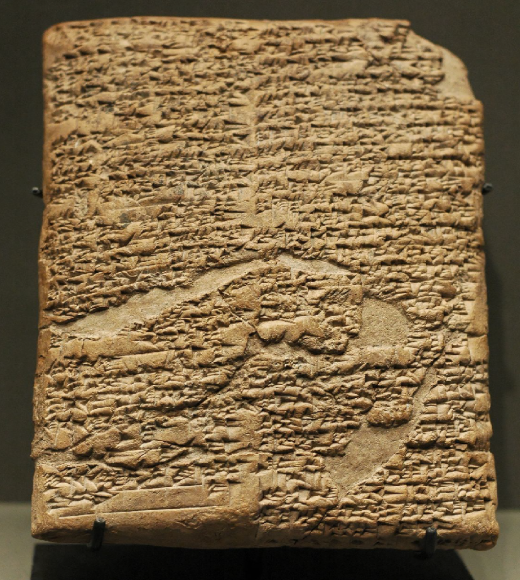

Retribution is thought to be the oldest punishment ideology, because it expresses a primordial concept of revenge, or “an eye for an eye.” This concept of vengeance implies that if someone perceives harm, they are within their rights to retaliate at a proportionatel level. The idea that retaliation against a transgression is allowable has ancient roots in the concept of Lex Talionis, which roughly translates as the “law of retaliation”. A person who injures someone should experience a similar amount of pain and suffering. The idea of Lex Talionis was developed in early Babylonian law, and it is here that we see some of the first written forms of justice policy. Dated to 1780 B.C.E., the Babylonian Code, or the Code of Hammurabi, is considered to be the first attempt to codify justice practices, or laws, within a societal formation. These laws (pictured below) largely represent a retributive approach to punishment.

The retributivist philosophy prohibits any suffering beyond what was originally intended by the offender, or by their sentencing. This is because proportionate punishment is a core principle of retribution: offenders who commit the same crime must receive the same punishment.