Chapter 17 Summary

The topics covered in this chapter can be summarized as follows:

| 17.1 | Factors That Control Stability on Slopes | Slope stability is controlled by the slope angle and the strength of the materials on the slope. Slopes are a product of tectonic uplift, and their strength is determined by the type of material on the slope and its water content. Rock strength varies widely and is determined by internal planes of weakness and their orientation with respect to the slope. In general, the more water, the greater the likelihood of failure. This is especially true for unconsolidated sediments, where excess water pushes the grains apart. Addition of water is the most common trigger of mass wasting, and can come from storms, rapid melting, or flooding. |

| 17.2 | Classification of Mass Wasting | The key criterion for classifying mass wasting is the nature of the movement that takes place. This may be a precipitous fall through the air, sliding as a solid mass along either a plane or a curved surface, or internal flow as a viscous fluid. The type of material that moves is also important — specifically whether it is solid rock or unconsolidated sediments. The important types of mass wasting are creep, slump, translational slide, rotational slide, fall, and debris flow or mudflow. |

| 17.3 | Preventing, Delaying, and Mitigating Mass Wasting | We cannot prevent mass wasting, but we can delay it through efforts to strengthen the materials on slopes. Strategies include adding mechanical devices such as rock bolts or ensuring that water can drain away. Such measures are never permanent, but may be effective for decades or even centuries. We can also avoid practices that make matters worse, such as cutting into steep slopes or impeding proper drainage. In some situations, the best approach is to mitigate the risks associated with mass wasting by constructing shelters or diversionary channels. And in other cases, where slope failure is inevitable, we should simply avoid building anything there. |

Exercises

Questions for Review

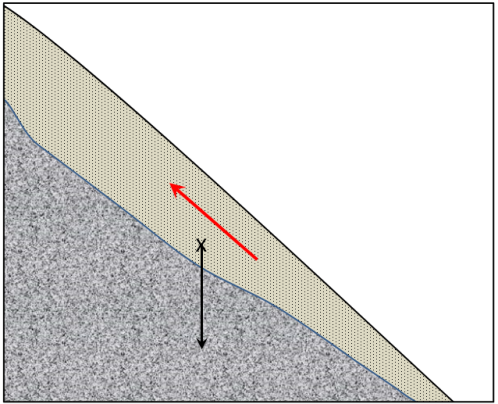

1. In the scenario shown here, the gravitational force on the unconsolidated sediment overlying the point marked with an X is depicted by the black arrow. Draw in the two arrows that show how this force can be resolved into the shear force (along the slope) and the normal force (into the slope).

1. In the scenario shown here, the gravitational force on the unconsolidated sediment overlying the point marked with an X is depicted by the black arrow. Draw in the two arrows that show how this force can be resolved into the shear force (along the slope) and the normal force (into the slope).

2. The red arrow in the diagram depicts the shear strength of the sediment. Assuming that the relative lengths of the shear force arrow (which you drew in question 1), and the shear strength arrow are indicative of the likelihood of failure, predict whether this material is likely to fail or not.

3. After several days of steady rain, the sediment becomes saturated with water and its strength is reduced by 25%. What are the likely implications for the stability of this slope?

4. In the diagrams shown here, a road cut is constructed in sedimentary rock with well-developed bedding. On the left, draw in the orientation of the bedding that would represent the greatest likelihood of slope failure. On the right, show the orientation that would represent the least likelihood of slope failure.

|

|

5. Explain why moist sand is typically stronger than either dry sand or saturated sand.

6. In the context of mass wasting, how does a flow differ from a slide?

7. If a large rock slide starts moving at a rate of several metres per second, what is likely to happen to the rock, and what would the resulting failure be called?

8. In what ways does a debris flow differ from a typical mudflow?

9. In the situation described in the chapter regarding lahar warnings at Mt. Rainier, the residents of the affected regions have to assume some responsibility and take precautions for their own safety. What sort of preparation should the residents make to ensure that they can respond appropriately when they hear lahar warnings?

10. What factors are likely to be important when considering the construction of a house near the crest of a slope that is underlain by glacial sediments?