I. Introduction to Civil Liberties Litigation

Bogard v. Cook

586 F.2d 399 (5th Cir. 1978), cert. denied 444 U.S. 883 (1979)

Before Clark, Fay, and Vance, Circuit Judges.

[1] William H. Bogard, a former prisoner at the Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman, Mississippi (“Parchman”), filed this action to recover civil damages for personal injuries. While a Parchman inmate, Bogard was subjected to a series of corporal punishments and suffered two incidents of prison violence, one a stabbing that severed his spinal cord and rendered him a permanent paraplegic. Bogard sued various supervisory officials, employees and inmates at Parchman, based on 42 U.S.C. § 1983 and pendent state tort claims.

I. The Facts

A. The Organization of the Parchman Prison

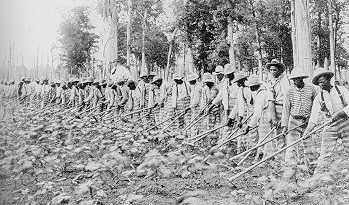

[2]The Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman is the only state prison in Mississippi. At the time Bogard was incarcerated at Parchman, the prison was operated essentially as it had been since 1903.

[3] Most of its 16,000 acres of farm land was devoted to growing cotton, soybeans and other cash crops, and the production of livestock, swine, poultry and milk. Mississippi law required Parchman to be financially self-sustaining, MISS. CODE ANN. § 47-5-1. The prison was expected to “operate at a profit at any cost.” Gates v. Collier, 349 F. Supp. 881, 892 (N.D. Miss. 1972). Consistent with this profit expectation, state law limited the number of prison employees to 150, “at such salaries as the penitentiary can afford.” MISS. CODE ANN. § 47-5-41. At the time of Bogard’s incarceration at Parchman, the inmate population numbered approximately 1,900. Two-thirds of the inmates were black, and prison facilities were segregated by race.

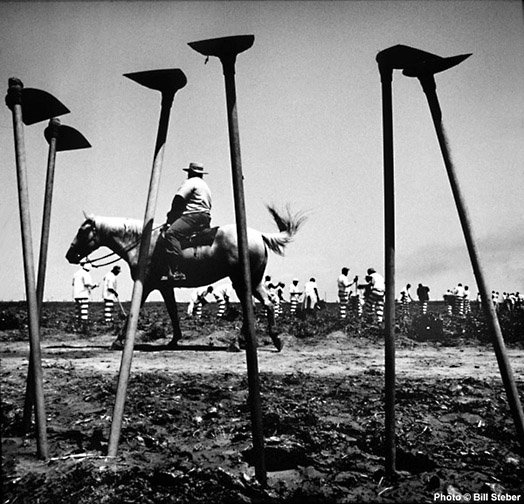

[4] Discipline and security at Parchman were maintained through the “trusty system,” a form of prison organization mandated by Mississippi law in which certain prisoners were selected to occupy positions ranging from armed guard to errand boy. See MISS. CODE ANN. § 47-5-143 (1972). In the terminology of the prison, the prisoners at the top of the “inside world” hierarchy were the “trusty shooters,” a group of about 150 inmate-guards armed with rifles and charged with the day-to-day guarding of the other inmates. Next came certain unarmed inmates, known simply as “trusties,” who assisted the prison’s civilian employees in various custodial and administrative capacities. “Hallboys” distributed medicine, delivered mail, and maintained files. “Floorwalkers” and “cage bosses” were charged with enforcing discipline and maintaining peace in the prison barracks; on their recommendation inmates could be punished. “Half-trusties,” also unarmed, served primarily as errand boys. The remaining inmates were known as “gunmen.”

[5] Parchman was physically divided into 21 separate units, the most important of which were the 12 major residential camps. Only four civilian employees, known as the “free worlders” were assigned to each residential camp. They consisted of a sergeant, who was in charge of the camp; two “drivers,” who supervised transporting inmates to and from field work; and one night watchman. Each residential camp contained barracks, known as “cages,” with separate wings for gunmen and trusties. Twenty to thirty trusty shooters were assigned to each camp.

Parchman Penitentiary By Bill Steber Source ©

[6] Parchman had a separate maximum security unit, which contained a special punishment area where inmates could be sent for violating prison rules. Each of the four wings of the maximum security unit contained 13 cells equipped for two men, with double metal bunks having no mattresses, a lavatory and a commode. In addition, each side of the maximum security unit contained a 6′ x 6′ cell, known as the “dark hole.” The dark hole had no windows, lights, commode, sink or other furnishings. A six-inch hole located in the middle of the concrete floor was provided for disposition of body wastes. A solid heavy metal door closed the cell. Mississippi law specifically authorized use of the dark hole punishment for periods of up to twenty-four hours. MISS. CODE ANN. § 47-5-145.

[7] State law vested overall responsibility and control of Parchman in the hands of the prison superintendent. The superintendent, appointed by the state penitentiary board, was exclusively “responsible for the management of affairs of the prison system and for the proper care, treatment, feeding, clothing and management of the prisoners.” MISS. CODE ANN. § 47-5-23. An assistant superintendent assisted the superintendent in his duties.

B. Bogard’s Injuries and Punishments at Parchman

[8] A twenty-two-year-old William Bogard arrived at Parchman in March of 1969, convicted of armed robbery and sentenced to twenty-five years’ imprisonment. Three years later a permanently paraplegic Bogard left Parchman on the clemency of the Governor. Bogard divides his allegations of injury into three categories: a rifle wound inflicted by a trusty shooter on February 25, 1971, a knife wound inflicted by a fellow inmate on July 7, 1972, and various summary punishments imposed at different times throughout his confinement.

[9] At the time of the shooting incident of February 25, 1971, Bogard was incarcerated at residential Camp Eight at Parchman. It was a cold morning and the prisoners at Camp Eight were demanding that the camp sergeant, defendant Fred Childs, provide them with warmer clothing. When their request was denied, the inmates staged a “buck,” a refusal to work. The striking inmates, including Bogard, were ordered to the Maximum Security Unit, and a truck was summoned to transport them.

[10] Pursuant to prison procedure, the truck was parked outside of the camp’s “gunline,” an imaginary line on the perimeter of the camp identified by markers. An unauthorized crossing of the gunline was considered an escape attempt and could be thwarted by gunfire. To safely cross the gunline and board the truck, a prisoner had to be “hollered out”—authorized to cross the line.

[11] Camp Sergeant Childs and trusty shooters Dougherty and Milton Davis were supervising the loading. Parchman’s Chief Security Officer, Jay Leland Vanlandingham, was standing nearby. Bogard and several other prisoners were ordered by Sergeant Childs to cross the gunline and board the truck. The inmates moved slowly. To hurry them up, trusty shooters Davis and Dougherty fired four to five rifle shots. One bullet struck Bogard in the foot. He was hospitalized for one month.

[12] Following the shooting incident, Bogard was transferred to Parchman’s disability facility, Camp Two, to recuperate from his gun wound. At Camp Two Bogard was appointed to the position of hallboy, a job in which he performed duties for the camp’s sergeant, defendant T.T. Peeks. Bogard’s duties included assisting with the daily roll call, preparing reports, keeping records, dispensing medication and handling mail.

[13] In July of 1972, Bogard, in his capacity as hallboy, informed Camp Sergeant Peeks that one of the camp’s inmates had a sewing machine in his possession in the “cage” the camp barracks. That inmate was defendant James B. “Slicker” Davis, one of the camp’s regular gunman prisoners. Sergeant Peeks ordered Bogard to go into the cage area and remove Slicker Davis’ sewing machine; Bogard obeyed the order. Several hours later Slicker Davis, armed with a boning knife obtained from the slaughterhouse where he worked, stabbed Bogard in the back. Davis struck Bogard with such force that the blade of the knife broke off inside Bogard’s back.

[14] Bogard was carried to the prison infirmary, where the two attending doctors disagreed as to whether he should be immediately sent to a hospital outside the prison. It was decided not to send Bogard out of Parchman; he was given a shot of Demerol and the doctors began their attempts to remove the portion of the blade that was still implanted in his spine. The blade was irregular in shape and deeply embedded; after several attempts to extract it failed, one of the attending doctors asked an assistant to find the strongest prisoner in the area and bring him to the infirmary. “Boss” Stapleton, an inmate of notorious physical strength, was summoned. Stapleton grasped the edge of the blade with a clamp and began to pull, lifting Bogard’s body off of the table with repeated efforts, until finally the blade came free.

[15] Bogard remained in the Parchman infirmary for three days, and was then transferred to the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson, Mississippi. At the University Hospital it was determined that the knife blade had severed Bogard’s spinal cord almost completely, rendering him a permanent paraplegic. On August 4, 1972, the Governor of Mississippi suspended the remainder of Bogard’s sentence and he was taken to his parents’ home in Harvey, Illinois.

[16] Unlike the circumstances surrounding Bogard’s shooting and stabbing injuries, the facts concerning various summary punishments inflicted against Bogard at Parchman are disputed and unclear. The practices Bogard complains of are imprisonment in the “dark hole,” “coke crate punishment” (being forced to stand for a long period of time on a small wooden box), the shaving of his head with sheep shears, and confinement for varying periods of time in the Maximum Security Unit’s punishment cell. It is undisputed that Bogard was in fact confined in both the punishment cells and dark hole of the Maximum Security Unit on several occasions, and that it was common practice to shave the heads of inmates confined in the dark hole. Testimony as to whether Bogard was given “coke crate punishment” is not completely clear, although the record does reveal that the coke crate punishment was used from time to time to discipline inmates. Because the exact nature of these summary punishments and the extent to which different defendants were aware of or sanctioned their use are issues central to the disposition of this appeal, a more exacting discussion of the evidence concerning summary punishments is reserved for Part IV of this opinion.

C. The Trial

[17] Bogard brought his suit for damages against Slicker Davis, the gunman inmate who stabbed him; Charles Dougherty and Milton Davis, the two inmate trusty shooters who fired the rifle shots that resulted in his gunshot wound of February 25, 1971; Sergeant T. T. Peeks, the sergeant in charge of Camp Two when Bogard was stabbed there; Sergeant Fred Childs, the sergeant in charge of Camp Eight who supervised the truck loading there when Bogard was shot; Dr. Hernando Abril, the Medical Director at Parchman who treated Bogard for his shooting and stabbing injuries; Jay Leland Vanlandingham, Chief Security Officer at Parchman; Jack Byars, Assistant Superintendent of Parchman; Thomas Cook, Superintendent at Parchman until February 13, 1972; and John Collier, Superintendent at Parchman from February 14, 1972, through the end of Bogard’s custody. Also named as a defendant was the United States Fidelity and Guaranty Company, by virtue of its fidelity undertakings for Superintendents Cook and Collier, and Assistant Superintendent Byars.

* * * * *

[18] Relative to the shooting incident, Bogard alleged that Superintendent Cook and Assistant Superintendent Byars were negligent or reckless in allowing Milton Davis and Charles Dougherty to serve as trusty shooters, because they were appointed without sufficient investigation into their backgrounds and qualifications. Bogard alleged that Cook and Byars were aware of and acquiesced in the use of the type of rifle fire by inmate trusty shooters that took place on the day he was shot but failed to correct such practices, and were negligent in hiring both Childs and Vanlandingham to work at Parchman. Regarding the stabbing, Bogard further alleged that it was the failure of Superintendent Collier (who had recently replaced Cook) and Byars to properly classify inmates according to their propensities for violence, and their use of half-trusty prisoners such as Bogard to assist in the control and supervision of inmates such as Slicker Davis, that led to Davis’ vicious attack. Finally, Bogard claimed that the prison officials were aware of and sanctioned his unjustified subjection to the coke crate, dark hole, and Maximum Security Unit punishments.

[19] Bogard asserted that the conduct of the defendants violated his eighth amendment right to be free from cruel and unusual punishment, and his fourteenth amendment right to be free from deprivations of liberty without due process. All of the defendants were also sued for the same conduct in a pendent claim under Mississippi tort law.

D. The Incomplete Verdict

[20] The trial was to a six person jury. Presentation of evidence took three weeks. At the conclusion of the evidence the court prepared a special verdict with thirty-six interrogatories. After a day’s deliberation, the court was informed that the jury had answered eighteen of the questions, but was deadlocked on the others. The court accepted the eighteen answers, repeated the charge and explanations on the unanswered interrogatories, and sent the jury back for further deliberation. This process was repeated several times and some additional answers were brought back, but after four days of delicate prodding by the court it became clear that the jury could not reach unanimous agreement on more than twenty-six of the thirty-six issues submitted. None of the parties assign as error the trial court’s acceptance of an incomplete verdict.

[21] As to each defendant, the jury was asked in a series of three separate questions whether the defendant (1) had been negligent in his duties, (2) the negligence was the proximate cause of Bogard’s injuries, and (3) the negligence was willful, wanton or gross. While there is room for some confusion both in the logic of the special verdict questions and in the jury’s answers to them, we construe the verdict as establishing that Bogard in fact suffered both constitutional and common law injuries in the form of summary punishments, the shooting, and the stabbing, but that all of the employee defendants except Cook, Collier and Byars were found by the jury to have acted within the scope of the qualified immunity on all counts. We further construe the jury’s failure to resolve the gross negligence questions with regard to Cook, Collier and Byars as a failure to resolve their qualified immunity defense on all counts.

[22] In capsule, the jury found virtually all of the defendants (Sergeant Peeks being the sole exception) negligent in their duties. However, only the two inmate defendants, trusty shooters Davis and Dougherty, were specifically found grossly, willfully or wantonly negligent. The jury explicitly decided that the lower and middle level prison employees—Vanlandingham and Childs—were not grossly, willfully, or wantonly negligent. As to the alleged gross, willful or wanton negligence of the management level officials—Cook, Collier and Byars—the jury could not agree. Cook and Byars were found to have subjected Bogard to cruel and unusual punishment, and all defendants save Vanlandingham and Dr. Abril were found to have deprived him of due process. The total jury awards against all defendants amounted to $500,000. [1]

E. The District Court’s Action

[23] In its Memorandum Opinion of November 11, 1975, the district court granted directed verdicts in favor of all defendants except gunman inmate Slicker Davis and trusty shooters Milton Davis and Dougherty. The controlling legal principle in the district court’s decision was that the prison employees were entitled to a qualified official immunity defense both under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 and Mississippi tort law. This shield of qualified immunity, the court held, can be pierced only on a showing of misconduct more egregious than ordinary negligence. Guided by this principle, judgment in favor of Sergeants Peeks and Childs and Security Officer Vanlandingham followed as a matter of course, since the jury specifically found that their conduct was not willful, wanton or gross. As to the three management level defendants Cook, Collier and Byars the court granted post-trial directed verdicts in this language:

Disposition of the motions sub judice has given the court cause to carefully consider the evidence introduced at trial. Upon mature reflection, the court has concluded that the evidence presented on the issue of whether the defendants Cook, Collier, and Byars acted in a wilful, wanton, or grossly negligent manner in connection with the shooting and stabbing injuries to plaintiff and the claims concerning violations of the plaintiff’s constitutional rights was insufficient to create a jury question on those points. In reaching this determination, the court has attempted to strictly adhere to the standard governing the granting of a directed verdict set forth in Boeing Co., v. Shipman, 411 F.2d 365 (5th Cir. 1969). After due deliberation on the matter, the court is of the opinion that a verdict should have been directed on this issue in favor of the aforementioned defendants during the course of the trial.

405 F. Supp. at 1208.

[24] Bogard appeals from the district court’s entry of these directed verdicts, claiming that under both state and federal law the defendants are not entitled to a qualified immunity defense, that the trial court evaluated the defendant’s liability under an incorrect standard of care, and that no directed verdict was justified.

* * * * *

II. Preliminary Issues

* * * * *

C. The Eleventh Amendment and Monell

[25] The plaintiff brought his suit against the Parchman defendants both in their individual and official capacities. Insofar as the defendants are sued in their individual capacities they enjoy a qualified immunity defense, and as we hold in Part IV, that defense absolves them of individual liability in this case. The plaintiff maintains, however, that when sued in their official capacities, the suit against the defendants becomes in effect a suit against the State of Mississippi. The plaintiff further argues that because the jury’s award would be paid by the State itself if the defendants are liable in their official capacities, the defense of qualified immunity would no longer be applicable.

[26] The flaw in the plaintiff’s argument is that he may not maintain this action against the State of Mississippi. Retrospective monetary relief against a state is barred by the eleventh amendment. Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651, 94 S. Ct. 1347, 39 L. Ed.2d 662 (1974). Since Bogard may not maintain this suit against the state, he may only seek recovery from the defendants as individuals. In that capacity, the qualified immunity defense is fully applicable.

III. QUALIFIED IMMUNITY

A. Federal Law

[27] In Procunier v. Navarette, 434 U.S. 555, 98 S. Ct. 855, 55 L. Ed.2d 24 (1978), the Supreme Court held that prison officials sued under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 were entitled to the qualified immunity defense that had previously been recognized in Scheuer v. Rhodes, 416 U.S. 232, 94 S. Ct. 1683, 40 L. Ed.2d 90 (1974) (state governor, university president and national guard members) and Wood v. Strickland, 420 U.S. 308, 95 S. Ct. 992, 43 L. Ed.2d 214 (1975) (school board members). See also O’Connor v. Donaldson, 422 U.S. 563, 95 S. Ct. 2486, 45 L. Ed.2d 396 (1975) (superintendent of state hospital).

[28] In Scheuer state officials were sued for damages under section 1983 for their involvement in shootings on the Kent State University campus during a Viet Nam anti-war demonstration. The Supreme Court held that a qualified immunity is available to executive officers, increasing in scope with the breadth of the officer’s discretion and responsibilities. See Slavin v. Curry, 574 F.2d 1256 (5th Cir. 1978). The court stated that the immunity is predicated on “the existence of reasonable grounds for belief formed at the time” of the official’s action “coupled with good-faith belief” that the action was proper. 416 U.S. at 247-48, 94 S. Ct. at 1692.

[29] Wood v. Strickland clarified the Scheuer defense by establishing a dual test for measuring the existence of qualified immunity which requires both an objective and a subjective measurement of official conduct. See Bryan v. Jones, 530 F.2d 1210, 1214 (5th Cir. 1976) (en banc). Under the objective test of Wood, an official, even if he is acting in the sincere subjective belief that he is doing right, loses his cloak of qualified immunity if his actions contravene “settled, indisputable law.” 95 S. Ct. at 1000. Navarette brought the objective part of the Wood formulation forward without alteration by this language:

Under the first part of the Wood v. Strickland rule, the immunity defense would be unavailing to petitioners if the constitutional right allegedly infringed by them was clearly established at the time of their challenged conduct, if they knew or should have known of that right and if they knew or should have known that their conduct violated the constitutional norm. 98 S. Ct. at 860.

[30] Under that second branch of the official immunity doctrine, an official forfeits his immunity, if whatever the objective state of the law at the time of his conduct, his subjective intent was to harm the plaintiff However, Wood did not definitively establish the extent to which conduct less egregious than an affirmative intent to harm simple negligence, gross negligence or recklessness would satisfy the subjective “malicious intent” requirement. Navarette appears to fill in that deficiency. The holding in Navarette squarely establishes that proof of simple negligence is not enough to pierce an official’s immunity under § 1983.

* * * * *

[31] [W]e read the malicious intent prong of the official immunity defense to require proof that an official either actually intended to do harm to the plaintiff, or took an action which, although not intended to do harm, was so likely to produce injury that the harm can be characterized as substantially certain to result. The spirit of the rule reaches nonfeasance as well as misfeasance. It does not insulate an official who, although not possessed of any actual malice or intent to harm, is so derelict in his duties that he must be treated as if he in fact desired the harmful results of his inaction. At the same time, however, the test requires that a plaintiff show that the official’s action, although labeled as “reckless” or “grossly negligent,” falls on the actual intent side of those terms, rather than on the side of simple negligence.

* * * * *

IV. THE DIRECTED VERDICT

[32] The district court directed a verdict in favor of Cook, Collier and Byars on the issue of whether their conduct rose to the level of willful, wanton or gross negligence. That verdict on the qualified immunity issue must be evaluated in light of Wood and the subsequent gloss of Navarette. Inquiry must be made into the subjective intent of Cook, Collier, and Byars, and the objective reasonableness of their actions when compared to the state of constitutional law concerning prisoners and prison conditions during the period from 1969 to 1970.

* * * * *

[33] Only Cook is implicated by the jury’s verdict in the shooting, and only Collier in the stabbing; Cook and Byars are implicated in the summary punishments. [2]

The evidence regarding the defendant’s qualified immunity will be discussed separately with regard to each claim.

A. The Shooting

[34] On February 25, 1971, the day Bogard was shot, Thomas Cook was Superintendent at Parchman. Cook was not present at the location of the shooting or in any sense directly involved in the incident. Bogard attempts to affix liability on Cook for the shooting by alleging that his injury was caused by Cook’s failure to properly administer the trusty guard system in the face of knowledge by Cook that the system was corrupt, disorderly and fraught with violence. Specifically, Bogard cites evidence that inmates were selected for the job of trusty shooter through a system of payoffs, favoritism and extortion, that those selected were often either serving time for crimes of violence, were mentally retarded or were suffering from psychological disorders, that after selection those chosen were not trained in the use of firearms or instructed as to proper procedures for the handling of an event such as an inmate “buck,” and that the ultimate product of the system was a regime of incessant armed violence on the part of the trusty shooters.

[35] Gates established that the picture Bogard paints of the trusty shooter system is an accurate one:

Penitentiary records indicate that many of the armed trusties have been convicted of violent crimes, and that of the armed trusties serving as of April 1, 1971, 35% had not been psychologically tested, 40% of those tested were found to be retarded, and 71% of those tested were found to have personality disorders. There is no formal program at Parchman for training trusties and they are instructed to maintain discipline by shooting at inmates who get out of the gun line; in many cases, trusties have received little training in the handling of firearms. Inmates have, on many occasions, suffered injuries and abuses as a result of the failure to select, train, supervise and maintain an adequate custodial staff. Trusties have abused their position to engage in loan-sharking, extortion and other illegal conduct in dealing with inmates subject to their authority and control. The evidence indicates that the use of trusties who exercise authority over fellow inmates has established intolerable patterns of physical mistreatment. For example, during the Cook administration, 30 inmates received gunshot wounds, an additional 29 inmates were shot at, and 52 inmates physically beaten.

349 F. Supp. at 889. It is no less accurate to state that the deplorable state of the trusty system was a proximate cause of Bogard’s shooting injury and that Cook was negligent in performing his duty to properly administer the system. The jury specifically found that Cook was negligent in his duties and that Cook’s negligence was a proximate cause of the shooting.

[36] To hold Cook personally liable, however, Bogard must overcome Cook’s qualified immunity. The district court held that there was insufficient evidence to create a jury question on whether Cook was guilty of anything worse than negligence. Applying the Navarette qualified immunity formulation, we agree with the district court that a directed verdict was proper.

[37] The indiscriminate violence of the trusty shooters at Parchman was primarily the result of factors endemic to the trusty system itself. Although the jury could properly have found that Cook’s failings as an administrator exacerbated an already corrupt and disorderly system, Cook’s complicity in failing to correct abuses does not rise to the level of reckless conduct, and certainly falls short of the malicious intent required by Wood and Navarette. At the time of Cook’s administration, state law restricted the superintendent to 150 civilian employees with whom to operate the prison, and only about 30 of those employees could feasibly be allocated to the actual work of guarding inmates. The nearly 2000 felons housed at Parchman were crammed in rundown and unsanitary quarters, and the superintendent had no funds or authorization to alleviate those explosive physical conditions. State law required Cook to use inmates to guard other inmates, but the legislature appropriated no money for obtaining the necessary staffing or expertise to psychologically test inmates for the position. The physical separation of the 12 residential camps necessitated that actual day-to-day supervision of prisoners be committed to the residential camp sergeants, and that selection for trusty status and demotions to the gunman level be placed largely in their hands. Corruption and violence within the trusty system at Parchman were entrenched by years of operation under these conditions.

[38] The only meaningful solution to the problems of the trusty system was its total elimination, the result ordered in Gates. If Cook had had at his disposal the means to eliminate the violent system but failed to do so, that failure would clearly make a jury issue as to whether it amounted to the malicious intent described in Navarette. But Cook was not only unauthorized to institute the only reform that would have been likely to eliminate the type of shooting suffered by Bogard, he was largely unable to take any meaningful intermediate step. Proper selection and adequate training of trusty shooters at Parchman was delegated by necessity to camp sergeants. If Cook failed to do the best he could with what he had, his failure was largely his admitted lack of control over those sergeants. In his brief Cook acknowledged that each sergeant “was almost like a warden of a separate unit,” and that the sergeants were protective of their independence and “resented interference from the administration building.” Although the jury found that Sergeant Childs at Camp Eight was not grossly negligent in his duties a factor that tends to blunt Bogard’s assertion that Cook was grossly negligent in delegating responsibility to him the record and the findings in Gates support the inference that it was the unbridled tyranny of camp sergeants at Parchman that fueled much of the violence there. Yet, given the financial resources and limitations on the number of guards he could hire, the Parchman superintendent could do little more to hire high quality camp sergeants than he could to eliminate the trusty system or build new housing. Superintendent Cook’s administration of Parchman was not a paragon, but nothing in the record showed it to be anything more than an inability to cope with a virtually hopeless situation, which the jury equated with a negligent failure to do as good a job as could reasonably have been done under these limitations.

B. The Stabbing

[39] Slicker Davis’ vicious stabbing of Bogard on July 7, 1972, like Bogard’s shooting injury, is more an indictment of Parchman itself than a result of personal involvement by prison supervisors. Bogard attempts to establish the liability of Superintendent Collier by asserting that Collier should have employed either metal detectors or frequent body searches to eliminate the widespread possession by inmates of weapons such as Slicker Davis’ knife, that Collier should have provided for the segregation of violent inmates such as Slicker Davis from nonviolent inmates like Bogard, and that Bogard should not have been required as part of his duties as half-trusty to supervise inmates such as Slicker Davis when such contact was an obvious and predictable source of resentment and violence.

[40] As in the case of the shooting, the causative factors Bogard lists for his stabbing are essentially accurate. There is no disputing the existence of the widespread possession of weaponry at Parchman, the failure to insulate the nonviolent from the violent or disturbed, and the charged atmosphere of resentment, suspicion and retaliation that was created by putting inmates in charge of other inmates. In Gates it was stated that:

Defendants have failed to properly classify and assign inmates to barracks, resulting in the intermingling of inmates convicted of aggravated violent crimes with those who are first offenders or convicted of nonviolent crimes… .

Although many inmates possess knives or other handmade weapons, there is no established requirement or procedure for conducting shakedowns to discover such weapons, nor is possession of weapons reported or punished. At least 85 instances are revealed by the record where inmates have been physically assaulted by other inmates. Twenty-seven of these assaults involved armed attacks in which an inmate was either stabbed, cut or shot.

349 F. Supp. at 888-889.

[41] The jury found that Collier’s own negligence was a contributing cause to the stabbing, but it strains credibility to assert that his failures to curb the possession of arms, properly classify inmates, or do away with the trusty system were in any sense the product of a subjective intent to cause harm.

[42] Collier was no less constrained by state law than Cook in being forced to use the trusty system. Allowing inmates such as Bogard to be used as half-trusty “hallboys” may have contributed to problems at Parchman, but half-trustys were necessary if Parchman were to be run. Mississippi, with its limit on money and guards, mandated that inmates should help run their own prison; the resentment which that requirement spawned was inevitable and beyond Collier’s control.

[43] In hindsight it is obvious that it was a mistake to put Bogard and Slicker Davis in close contact. It is not clear, however, that the mistake can even be attributed to Collier, and it is definitely clear that if it was attributable to him, the mistake in no sense partook of an intent to harm Bogard. Camp 2, where Davis was housed, was reserved for those inmates suffering from a physical disability or who because of age or other infirmity were otherwise unable to perform Parchman’s normal routine of farm work. Slicker Davis was apparently confined to Camp 2 because of an infectious disease. Davis had already been assigned to Camp 2 when Collier took over as Superintendent. Bogard’s assignment to Camp 2 was also made prior to Collier’s assumption of duties, that assignment followed as a matter of course after Bogard’s shooting injury. Prior to the stabbing, there were no adverse reports concerning either Bogard or Davis which could have brought either man to Collier’s attention, and Collier had apparently had no contact with either inmate before that date. Several experts testified that on the basis of Slicker Davis’ file they would not have ordered him separated from other inmates. Collier’s failure to examine Davis’ file and then segregate Davis on his own initiative when no precipitating event had brought Davis to his attention can certainly not be characterized as the type of action or inaction which Navarette would condemn. It may well be that Parchman was generally deficient in its psychological testing of inmates and in its lack of physical facilities for the separation and supervision of the violent or disturbed, but as in the case of all the other major shortcomings of the prison, the primary cause was neglect by the State itself.

[44] As to the issue of weapons control, there was expert testimony that weapon possession is a problem in all prisons, and that prison administrators across the country have had only limited success in coping with the problem. Some prisons have installed airport-style weapons detectors and then abandoned their use because they fail to significantly reduce weapon possession. The record raises a substantial doubt as to whether metal detectors, had Collier decided to use them, and had he possessed funds to purchase them, would have even been obtainable. See 405 F. Supp. at 1211-12. Frequent physical searches are apparently the most effective means of combatting weapon possession, but a level of possession persists even under that method. The record shows that weapons searches did take place from time to time. Although weapons possession at Parchman was widespread and Collier appears to have taken no effective steps to bring it under control, his fault was not shown to be any worse than a negligent failure to adopt the best choice among the alternatives at his disposal.

C. The Summary Punishments

[45] The summary punishments Bogard complains of were of three types: incarceration in the punishment cell of the maximum security unit, incarceration in the dark hole, and the coke crate punishment. The incidents all occurred between June of 1969 and October of 1970. The punishments were alleged to be cruel and unusual, and inflicted without proper procedural due process.

[46] Bogard alleged that he was placed in a cell in the punishment wing of the maximum security unit six different times, for periods from two to thirty days. On at least two occasions, he claims, he was stripped naked when placed in the punishment cell, and as a matter of routine he was fed only once per day when confined there. In one instance he was allegedly confined in the punishment cell for three days and fed only once for the infraction of playing his radio too loudly. Bogard asserts four separate confinements in the dark hole, all for periods of 24 hours. Each confinement included being stripped naked and having his head shaved with heavy duty clippers that he characterizes as sheep shears. Bogard complains of only one subjection to the coke crate punishment. The punishment was allegedly ordered by his residential camp sergeant for Bogard’s failure to pick cotton fast enough; it consisted of being forced to stand on top of a coke crate box for an entire work day, for three consecutive days. These punishments are alleged to be cruel and unusual in their own right, and administered for petty offenses disproportionate to their severity. The dark hole and coke crate punishments were claimed to have been inflicted without any due process safeguards.

[47] There is ample evidence in the record that the punishment practices Bogard complains of were in routine use during the 1969-1970 period at Parchman. Gates established a lack of procedural due process in the use of severe punishments, and the fact that, as they were administered, the dark hole and punishment cell violated the eighth amendment. Gates also explicitly found that the Parchman superintendent and other prison officials acquiesced in the unconstitutional punishment procedures:

Mr. Cook defended the use of the dark hole as a necessary type of psychological punishment for inmates who are obstreperous, obstinate violators of penitentiary discipline, and favored that method in preference to inflicting corporal punishment by the lash. When this action was begun, however, the practice was to place inmates in the dark hole naked, without any hygienic materials, and often without adequate food. It was customary to cut the hair of an inmate confined in the dark hole by means of heavy-duty clippers described by inmates as sheep shears, which in some cases resulted in injury. Under the present practice inmates have frequently been kept in the dark hole for 48 hours and may be confined therein for up to 72 hours. While an inmate occupies the dark hole, the cell is not cleaned, nor is the inmate permitted to wash himself.

Although Superintendents Cook and Collier have issued instructions prohibiting mistreatment in the enforcement of discipline, the record is replete with innumerable instances of physical brutality and abuse in disciplining inmates who are sent to MSU (Maximum Security Unit). These include administering milk of magnesia as a form of punishment, stripping inmates of their clothes, turning the fan on inmates while naked and wet, depriving inmates of mattresses, hygenic materials and adequate food, handcuffing inmates to the fence and to cells for long periods of time, shooting at and around inmates to keep them standing or lying in the yard at MSU, and using a cattle prod to keep inmates standing or moving while at MSU. Indeed, the superintendents and other prison officials acquiesced in these punishment procedures.

349 F. Supp. at 890.

[48] The testimony of Cook and Byars indicates that they were fully aware of the nature of the dark hole and punishment cell and the indignities incident to those punishments. Head shaving with heavy clippers, for example, was defended by Cook as a badge of infamy that increased the psychological effectiveness of the dark hole; stripping of inmates for punishment was allegedly done for the inmates’ own protection. Byers admitted in this testimony that he was aware of the use of the coke crate punishment at Camp 8, as well as the use of camp punishments at other residential camps.

[49] The jury found that Cook and Byars had subjected Bogard to cruel and unusual punishment and deprivations of due process. The jury did not answer the question which asked whether Bogard suffered injury as a result of these constitutional violations but the jury did award him a total of $80,000 damages for the due process violations and cruel and unusual punishments. When the jury’s verdict and the findings in Gates are combined, the result is a conclusion that Cook and Byers were personally involved in subjecting Bogard to constitutional violations.

[50] The qualified immunity issue is more complex in the context of the summary punishments than in the context of the stabbing or shooting. Virtually by definition, infliction of the punishments involved a subjective intent to cause harm. Cook and Byars knew what the punishments consisted of, and in the case of punishments such as the dark hole, had to personally authorize each instance of their use. Harm, in the sense of “teaching an inmate a lesson,” was the obvious objective of punishment at Parchman. If intent of this sort is enough to satisfy the subjective prong of Wood and Navarette, the ultimate finding that the punishments were unconstitutional would complete the establishment of the defendant’s liability.

[51] To define the defendant’s subjective state of mind by a mechanical equation of punishment with intent, however, would ultimately eliminate the qualified immunity defense in the context of eighth amendment violations. If intent to harm is involved in any punishment that later turns out to be unconstitutional, the effect is to accomplish what the first prong of Wood specifically forbids: the imposition of liability for the failure to predict the future course of constitutional law. See Wood, 95 S. Ct. at 1001; O’Connor v. Donaldson, 422 U.S. 563, 95 S. Ct. 2486, 2495, 45 L. Ed.2d 396 (1975); Pierson v. Ray, 386 U.S. 547, 557, 87 S. Ct. 1213, 1219, 18 L. Ed.2d 288 (1967). If Cook and Byars could not have known in 1969-1970 that the punishment practices at Parchman were unconstitutional, they may not now be held liable merely because punishment inherently tends to connote an intent to cause harm. The record does not support any assertion that Cook or Byars harbored any subjective malicious desire to “get” Bogard as a specific individual. The overall subjective intent inquiry thus requires a limited objective inquiry into what Cook and Byars should have known about the legality of the punishments they sanctioned. Only if the punishments suffered by Bogard were clearly unconstitutional in 1969-1970 can it be said that Byars or Cook acted in bad faith. Under this formulation of the qualified immunity issue, it can be seen that the liability of the defendants for the summary punishments does not turn on a jury question at all. Since no issue of particularized malice toward Bogard was present, the only factual issues were the actual existence of eighth amendment and due process violations against Bogard issues which the jury resolved in Bogard’s favor. Whether the defendants should have known that their conduct violated the constitution is a purely legal inquiry that may be determined on this appeal.

[52] In 1969 and 1970, there was yet to be a decision of either this court, the Mississippi Supreme Court, or the United States Supreme Court that could have alerted the defendants that the punishments Bogard suffered were unconstitutional. At that time, federal courts were still generally reluctant to interfere with prison administration. The so-called “hands off” doctrine, see 18 A.L.R. Fed. 7 (1974), usually resulted in the denial of relief under federal civil rights acts for practices such as corporal punishment, punitive segregation, or harsh confinement conditions.

* * * * *

[53] The grant of relief in prisoner suits of this type did not begin in this circuit until 1972… . It was Gates v. Collier in 1974, however, that first marked a broad-scale intervention by this court in the supervision of prison practices.

[54] 1974 also recorded the Supreme Court’s most meaningful recognition of due process rights of prisoners in Wolff v. McDonnell, 418 U.S. 539, 94 S. Ct. 2963, 41 L. Ed.2d 935 (1974), but the Court expressly held that Wolff’s new pronouncement should not be given retroactive effect. This court’s decision affirming the district court in Gates was held in abeyance pending the decision in Wolff, Gates v. Collier, 501 F.2d at 1295 (1974), further attesting to the unsettled state of the law prior to that decision.

[55] Experts testified that punishments such as the dark hole were in common use in prisons around the country in 1969-1970. We acknowledged the national use of punishment cells similar to Parchman’s in Novak. 453 F.2d at 665. See also Poindexter v. Woodson, 510 F.2d 464, 465 (10th Cir. 1975) (noting the prevalence of solitary “strip cell” confinement in United States prisons). Clearly, the dark hole and punishment cells were long established procedures at Parchman. Perhaps most telling of all, Mississippi law expressly authorized use of the dark hole punishment for up to 24 hours. MISS. CODE § 47-5-145. The defendants cannot be held liable for failing to predict that an existing state statute would later be found constitutionally deficient. See Jagnandan v. Giles, 538 F.2d 1166, 1173 (5th Cir. 1976). In short, the law of 1970 was not highly protective of prisoners’ rights and courts were reluctant to intrude into the prison administrator’s domain. The defendants cannot reasonably be charged with knowledge that the punishment practices at Parchman were unconstitutional.

V. CONCLUSION

[56] Bogard proved his case against Parchman itself, but not against the individual defendants. The state was not and could not be brought before this Court, however, and it does not serve the ends of justice to fix monetary accountability on the state’s employees when they did little more than administer their positions during a time of state perpetuation of intolerable conditions over which they had no meaningful control. The absence of evidence in the record of malicious intent by prison officials, and the still dormant state of judicial recognition of prisoners’ rights in 1970 establishes that they were entitled to the defense of official immunity, which, as the district court correctly held, precluded their liability.

Affirmed.

Footnotes

-

Interrogatory number 36 asked the jury what damages would compensate Bogard for his various injuries. The jury awarded Bogard $20,000 compensation for his cruel and unusual punishments and $20,000 for his deprivations of due process during the Cook administration at Parchman, and another $20,000 for cruel and unusual punishments and $20,000 for deprivations of due process during Collier’s administration. The jury found, in addition, that $20,000 would compensate Bogard for his shooting injury and $400,000 would compensate him for his stabbing injury. ↵

-

Collier is not implicated in the shooting or the summary punishments because those incidents occurred prior to his assumption in office. The jury found that Cook was not implicated in the stabbing, which took place after he left Parchman. Byar’s negligence was found by the jury not to be a proximate cause of either the shooting or stabbing, leaving him potentially liable only for the summary punishments. ↵

Notes on Bogard v. Cook: Introduction to Civil Rights Litigation

- An essential component of any scheme of constitutional protection is the legal system’s willingness to award a meaningful remedy to persons injured by the government’s deprivation of individual liberty. English common law[1] and international human rights instruments demand that victims of official misconduct have recourse to effective relief.[2] 137, 163 (1803): As Chief Marshall recognized in Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch)

“The very essence of civil liberty certainly consists in the right of every individual to claim the protection of the laws, whenever he receives an injury. One of the first duties of government is to afford that protection.

* * * * *

The government of the United States has been emphatically termed a government of laws, and not of men. It will certainly cease to deserve this high appellation, if the laws furnish no remedy for the violation of a vested legal right.”

Traditional courses in constitutional law, which analyze the boundaries of rights guaranteed by the United States Constitution but ignore the circumstances under which a remedy will or will not be afforded for transgression of those rights, fail to identify the true protections afforded by the Constitution. This book instead begins with the premise that constitutional rights have been violated and focuses upon the availability of remedies for such violations.

- While the United States Constitution establishes individual rights protected against incursion by the government, the charter does not generally provide remedies for breach of those rights. Consequently, Congress and the courts have borne the responsibility of creating and demarcating remedies for deprivations of constitutional rights. In other words, where a constitutional right has been invaded by the government or its officials, the government itself furnishes the remedy. The extent of our government’s willingness to afford redress for its own misconduct is perhaps the most telling test of whether it is indeed a “government of laws” as well as a rightful measure of the individual rights guaranteed by the Constitution.

- Bogard v. Cook introduces several of the issues confronted in civil liberties litigation, although the contours of the substantive law have changed in the years following the Bogard decision. The overarching question is, given that an individual’s constitutional rights have been violated, who should bear the loss resulting from that violation?

- As a matter of policy, who should bear the risk of loss from constitutional deprivations? The individual government official who caused the violation? The government entity that employs the official who caused the violation? The individual government official and the entity? The victim?

- How is the risk of loss allocated among private actors under our common law tort system? Should the risk allocation differ for constitutional violations caused by government actors?

- Under what conditions should our legal system impose liability for constitutional violations? Should the government and its employees be strictly liable for all constitutional violations? Liable for violations caused by negligent conduct? Reckless conduct? Only intentional violations of the Constitution?

- What degree of defendant’s culpability must an injured person prove to recover damages for tortious conduct by private actors? Should the standard of culpability differ for deprivations of constitutional rights caused by government actors?

- For each of the incidents in Board–the shooting, the stabbing and the summary punishment:

- Which person(s) did Bogard seek to hold liable?

- For what conduct did Bogard attempt to hold the defendant(s) liable?

- Did the court find that the defendant(s) violated Bogard’s constitutional rights?

- With what degree of culpability did the court find the defendant(s) acted?

- Was the defendant(s) held liable? Why or why not?

↵

-

See 3 WILLIAM BLACKSTONE, COMMENTARIES ON THE LAWS OF ENGLAND: IN FOUR BOOKS 109 (London, A. Strahan 1803) (“[I]t is a [well] settled and invariable principle in the laws of England, that every right when withheld must have a remedy, and every injury its proper redress.”); Ashby v. White, ( 1703) 92 Eng. Rep. 126 (K.B.) (awarding 200 pounds to plaintiff for denial of the right to vote) (“If the plaintiff has a right, he must of necessity have a means to vindicate and maintain it [A]nd indeed it is a vain thing to imagine a right without a remedy; for want of [a] right and want of [a] remedy are reciprocal.”). See also ALBERT VENN DICEY, INTRODUCTION TO THE STUDY OF THE LAW OF THE CONSTITUTION, 198 (10th ed. 1959) (“[T]he question [of] whether the right to personal freedom … is likely to be secure depend[s] a good deal upon the answer to the inquiry whether the persons who consciously or unconsciously build up[on] the constitution[s] of their country begin with definitions or declarations of rights, or with the contrivance of remedies by which rights may be enforced or secured.”); Lord Denning, Misuse of Power, AUSTR. L.J. 720, 720 (1981) (“The only admissible remedy for any [misuse] of power—in a civilized society—is by recourse to law. In order to ensure this recourse, it is important that the law itself should provide adequate and efficient remedies for [the] abuse or misuse of power from whatever quarter it may come.”); see also Nelles v. Ontario [1989] 2 S.C.R. 170 (Can.) (“[A]ccess to a court of competent jurisdiction to seek a remedy is essential for the vindication of a constitutional wrong. To create a right without a remedy is antithetical to one of the purposes of the [Canadian] Charter [of Rights and Freedoms] which surely is to allow the courts to fashion remedies when constitutional infringements occur.”) (emphasis added).

↵ -

See Universal Declaration of Human Rights, G.A. Res. 217A, at art. 8, U.N. GAOR, 3d sess., 1st plen. mtg., U.N. Doc. A/810 (Dec. 12, 1948) (“Everyone has the right to an effective remedy by the competent national tribunals for acts violating the fundamental rights granted him by the [C]onstitution or by law.”); International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI), at art. 2, U.N. Doc. A/6316 (Dec. 16, 1966) (“Each State Party to the present Covenant undertakes: to ensure that any person whose rights or freedoms as herein recognized are violated shall have an effective remedy ”); International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination, G.A. Res. 2106 (XX, at art. 6, U.N. Doc. A/6014 (Dec. 12, 1965) (“State Parties shall assure to everyone within their jurisdiction effective protection and remedies, through the competent national tribunals and other State institutions, against any acts of racial discrimination as well as the right to seek from such tribunals just and adequate reparation or satisfaction for any damage suffered as a result of such discrimination.”); American Convention on Human Rights art. 25(1), July 18, 1978, 1144 U.N.T.S. 128 (“Everyone has the right to simple and prompt recourse to a competent court or tribunal for protection against acts that violate his fundamental rights recognized by the constitution or laws of the state concerned or by this Convention, even though such violation[s] may have been committed by persons acting in the course of their official duties.”).

↵