A. Introduction to Section 1983

42 U.S.C. § 1983

Every person who, under color of any statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage, of any State or Territory or the District of Columbia, subjects, or causes to be subjected, any citizen of the United States or other person within the jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution and laws, shall be liable to the party injured in any action at law, suit in equity, or other proper proceeding for redress. For the purposes of this section, any Act of Congress applicable exclusively to the District of Columbia shall be considered to be a statute of the District of Columbia.

MONROE v. PAPE, 365 U.S. 167 (1961)

Mr. Justice Douglas delivered the opinion of the Court.

[1]This case presents important questions concerning the construction of R.S. § 1979, 42 U.S.C. § 1983, which reads as follows:

“Every person who, under color of any statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage, of any State or Territory, subjects, or causes to be subjected, any citizen of the United States or other person within the jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution and laws, shall be liable to the party injured in an action at law, suit in equity, or other proper proceeding for redress.”

[2]The complaint alleges that 13 Chicago police officers broke into petitioners’ home in the early morning, routed them from bed, made them stand naked in the living room, and ransacked every room, emptying drawers and ripping mattress covers. It further alleges that Mr. Monroe was then taken to the police station and detained on “open” charges for 10 hours, while he was interrogated about a two-day-old murder, that he was not taken before a magistrate, though one was accessible, that he was not permitted to call his family or attorney, and that he was subsequently released without criminal charges being preferred against him. It is alleged that the officers had no search warrant and no arrest warrant and that they acted “under color of the statutes, ordinances, regulations, customs and usages” of Illinois and of the City of Chicago. Federal jurisdiction was asserted under R.S. § 1979, which we have set out above, and 28 U.S.C. § 1343 [1]

28 U.S.C. § 1331. [2]

Subsection (a) provides: “The district courts shall have original jurisdiction of all civil actions wherein the matter in controversy exceeds the sum or value of $10,000, exclusive of interest and costs, and arises under the Constitution, laws, or treaties of the United States.” In their complaint, petitioners also invoked R.S. §§ 1980, 1981, 42 U.S.C. §§ 1985, 1986. Before this Court, however, petitioners have limited their claim to recovery to the liability imposed by § 1979. Accordingly, only that section is before us.

[3]The City of Chicago moved to dismiss the complaint on the ground that it is not liable under the Civil Rights Acts nor for acts committed in performance of its governmental functions. All defendants moved to dismiss, alleging that the complaint alleged no cause of action under those Acts or under the Federal Constitution. The District Court dismissed the complaint. The Court of Appeals affirmed, 272 F.2d 365, relying on its earlier decision, Stift v. Lynch, 267 F.2d 237. The case is here on a writ of certiorari which we granted because of a seeming conflict of that ruling with our prior cases. 362 U.S. 926.

I.

[4]Petitioners claim that the invasion of their home and the subsequent search without a warrant and the arrest and detention of Mr. Monroe without a warrant and without arraignment constituted a deprivation of their “rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution” within the meaning of R.S. § 1979. It has been said that when 18 U.S.C. § 241 made criminal a conspiracy “to injure, oppress, threaten, or intimidate any citizen in the free exercise or enjoyment of any right or privilege secured to him by the Constitution,” it embraced only rights that an individual has by reason of his relation to the central government, not to state governments. United States v. Williams, 341 U.S. 70. Cf. United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542; Ex parte Yarbrough, 110 U.S. 651; Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347. But the history of the section of the Civil Rights Act presently involved does not permit such a narrow interpretation.

[5]Section 1979 came onto the books as § 1 of the Ku Klux Act of April 20, 1871. 17 Stat. 13. It was one of the means whereby Congress exercised the power vested in it by § 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment to enforce the provisions of that Amendment. Senator Edmunds, Chairman of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, said concerning this section:

“The first section is one that I believe nobody objects to, as defining the rights secured by the Constitution of the United States when they are assailed by any State law or under color of any State law, and it is merely carrying out the principles of the civil rights bill, which has since become a part of the Constitution,” viz., the Fourteenth Amendment.

[6]Its purpose is plain from the title of the legislation, “An Act to enforce the Provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, and for other Purposes.” 17 Stat. 13. Allegation of facts constituting a deprivation under color of state authority of a right guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment satisfies to that extent the requirement of R.S. § 1979. See Douglas v. Jeannette, 319 U.S. 157, 161-162. So far petitioners are on solid ground. For the guarantee against unreasonable searches and seizures contained in the Fourth Amendment has been made applicable to the States by reason of the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Wolf v. Colorado, 338 U.S. 25; Elkins v. United States, 364 U.S. 206, 213.

II.

[7]There can be no doubt at least since Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339, 346-347, that Congress has the power to enforce provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment against those who carry a badge of authority of a State and represent it in some capacity, whether they act in accordance with their authority or misuse it. See Home Tel. & Tel. Co. Los Angeles, 227 U.S. 278, 287-296. The question with which we now deal is the narrower one of whether Congress, in enacting § 1979, meant to give a remedy to parties deprived of constitutional rights, privileges and immunities by an official’s abuse of his position. Cf. Williams v. United States, 341 U.S. 97; Screws v. United States, 325 U.S. 91; United States v. Classic, 313 U.S. 299. We conclude that it did so intend.

[8]It is argued that “under color of” enumerated state authority excludes acts of an official or policeman who can show no authority under state law, state custom, or state usage to do what he did. In this case it is said that these policemen, in breaking into petitioners’ apartment, violated the Constitution and laws of Illinois. It is pointed out that [3] under Illinois law a simple remedy is offered for that violation and that, so far as it appears, the courts of Illinois are available to give petitioners that full redress which the common law affords for violence done to a person; and it is earnestly argued that no “statute, ordinance, regulation, custom or usage” of Illinois bars that redress.

[9]The Ku Klux Act grew out of a message sent to Congress by President Grant on March 23, 1871, reading:

“A condition of affairs now exists in some States of the Union rendering life and property insecure and the carrying of the mails and the collection of the revenue dangerous. The proof that such a condition of affairs exists in some localities is now before the Senate. That the power to correct these evils is beyond the control of State authorities I do not doubt; that the power of the Executive of the United States, acting within the limits of existing laws, is sufficient for present emergencies is not clear. Therefore, I urgently recommend such legislation as in the judgment of Congress shall effectually secure life, liberty, and property, and the enforcement of law in all parts of the United States “

[10]The legislation—in particular the section with which we are now concerned—had several purposes. There are threads of many thoughts running through the debates. One who reads them in their entirety sees that the present section had three main aims.

[11]First, it might, of course, override certain kinds of state laws. Mr. Sloss of Alabama, in opposition, spoke of that object and emphasized that it was irrelevant because there were no such laws:

“The first section of this bill prohibits any invidious legislation by States against the rights or privileges of citizens of the United States. The object of this section is not very clear, as it is not pretended by its advocates on this floor that any State has passed any laws endangering the rights or privileges of the colored people.”

[12]Second, it provided a remedy where state law was inadequate. That aspect of the legislation was summed up as follows by Senator Sherman of Ohio:

“… it is said the reason is that any offense may be committed upon a negro by a white man, and a negro cannot testify in any case against a white man, so that the only way by which any conviction can be had in Kentucky in those cases is in the United States courts, because the United States courts enforce the United States laws by which negroes may testify.”

[13]But the purposes were much broader. The third aim was to provide a federal remedy where the state remedy, though adequate in theory, was not available in practice. The opposition to the measure complained that “It overrides the reserved powers of the States,” [4] just as they argued that the second section of the bill “absorb[ed] the entire jurisdiction of the States over their local and domestic affairs.”

[14]This Act of April 20, 1871, sometimes called “the third ‘force bill,'” was passed by a Congress that had the Klan “particularly in mind.” The debates are replete with references to the lawless conditions existing in the South in 1871. There was available to the Congress during these debates a report, nearly 600 pages in length, dealing with the activities of the Klan and the inability of the state governments to cope with it. [5] This report was drawn on by many of the speakers. It was not the unavailability of state remedies but the failure of certain States to enforce the laws with an equal hand that furnished the powerful momentum behind this “force bill.”

Mr. Lowe of Kansas said:

“While murder is stalking abroad in disguise, while whippings and lynchings and banishment have been visited upon unoffending American citizens, the local administrations have been found inadequate or unwilling to apply the proper corrective. Combinations, darker than the night that hides them, conspiracies, wicked as the worst of felons could devise, have gone unwhipped of justice. Immunity is given to crime, and the records of the public tribunals are searched in vain for any evidence of effective redress.”

[15]Mr. Beatty of Ohio summarized in the House the case for the bill when he said:

“… certain States have denied to persons within their jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. The proof on this point is voluminous and unquestionable…. Men were murdered, houses were burned, women were outraged, men were scourged, and officers of the law shot down; and the State made no successful effort to bring the guilty to punishment or afford protection or redress to the outraged and innocent. The State, from lack of power or inclination, practically denied the equal protection of the law to these persons.”

[16]While one main scourge of the evil—perhaps the leading one—was the Ku Klux Klan, the remedy created was not a remedy against it or its members but against those who representing a State in some capacity were unable or unwilling to enforce a state law.

[17]Mr. Hoar of Massachusetts stated:

“Now, it is an effectual denial by a State of the equal protection of the laws when any class of officers charged under the laws with their administration permanently and as a rule refuse to extend that protection. If every sheriff in South Carolina refuses to serve a writ for a colored man and those sheriffs are kept in office year after year by the people of South Carolina, and no verdict against them for their failure of duty can be obtained before a South Carolina jury, the State of South Carolina, through the class of officers who are its representatives to afford the equal protection of the laws to that class of citizens, has denied that protection. If the jurors of South Carolina constantly and as a rule refuse to do justice between man and man where the rights of a particular class of its citizens are concerned, and that State affords by its legislation no remedy, that is as much a denial to that class of citizens of the equal protection of the laws as if the State itself put on its statute-book a statute enacting that no verdict should be rendered in the courts of that State in favor of this class of citizens.”

* * * * *

[18]It was precisely that breadth of the remedy which the opposition emphasized. Mr. Kerr of Indiana referring to the section involved in the present litigation said:

“This section gives to any person who may have been injured in any of his rights, privileges, or immunities of person or property, a civil action for damages against the wrongdoer in the Federal courts. The offenses committed against him may be the common violations of the municipal law of his State. It may give rise to numerous vexations and outrageous prosecutions, inspired by mere mercenary considerations, prosecuted in a spirit of plunder, aided by the crimes of perjury and subornation of perjury, more reckless and dangerous to society than the alleged offenses out of which the cause of action may have arisen. It is a covert attempt to transfer another large portion of jurisdiction from the State tribunals, to which it of right belongs, to those of the United States. It is neither authorized nor expedient, and is not calculated to bring peace, or order, or domestic content and prosperity to the disturbed society of the South. The contrary will certainly be its effect.”

[19]Senator Thurman of Ohio spoke in the same vein about the section we are now considering:

“It authorizes any person who is deprived of any right, privilege, or immunity secured to him by the Constitution of the United States, to bring an action against the wrong-doer in the Federal courts, and that without any limit whatsoever as to the amount in controversy. The deprivation may be of the slightest conceivable character, the damages in the estimation of any sensible man may not be five dollars or even five cents; they may be what lawyers call merely nominal damages; and yet by this section jurisdiction of that civil action is given to the Federal courts instead of its being prosecuted as now in the courts of the States.”

[20]The debates were long and extensive. It is abundantly clear that one reason the legislation was passed was to afford a federal right in federal courts because, by reason of prejudice, passion, neglect, intolerance or otherwise, state laws might not be enforced and the claims of citizens to the enjoyment of rights, privileges, and immunities guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment might be denied by the state agencies.

* * * * *

[21]Opponents of the Act, however, did not fail to note that by virtue of § 1 federal courts would sit in judgment on the misdeeds of state officers. Proponents of the Act, on the other hand, were aware of the extension of federal power contemplated by every section of the Act. They found justification, however, for this extension in considerations such as those advanced by Mr. Hoar:

“The question is not whether a majority of the people in a majority of the States are likely to be attached to and able to secure their own liberties. The question is not whether the majority of the people in every State are not likely to desire to secure their own rights. It is, whether a majority of the people in every State are sure to be so attached to the principles of civil freedom and civil justice as to be as much desirous of preserving the liberties of others as their own, as to insure that under no temptation of party spirit, under no political excitement, under no jealousy of race or caste, will the majority either in numbers or strength in any State seek to deprive the remainder of the population of their civil rights.”

[22]Although the legislation was enacted because of the conditions that existed in the South at that time, it is cast in general language and is as applicable to Illinois as it is to the States whose names were mentioned over and again in the debates. It is no answer that the State has a law which if enforced would give relief. The federal remedy is supplementary to the state remedy, and the latter need not be first sought and refused before the federal one is invoked. Hence the fact that Illinois by its constitution and laws outlaws unreasonable searches and seizures is no barrier to the present suit in the federal court.

[23]We had before us in United States v. Classic, supra, § 20 of the Criminal Code, 18 U.S.C. § 242, which provides a criminal punishment for anyone who “under color of any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom” subjects any inhabitant of a State to the deprivation of “any rights, privileges, or immunities secured or protected by the Constitution or laws of the United States.” Section 242 first came into the law as § 2 of the Civil Rights Act, Act of April 9, 1866, 14 Stat. 27. After passage of the Fourteenth Amendment, this provision was re-enacted and amended by §§ 17, 18, Act of May 31, 1870, 16 Stat. 140, 144. The right involved in the Classic case was the right of voters in a primary to have their votes counted. The laws of Louisiana required the defendants “to count the ballots, to record the result of the count, and to certify the result of the election.” United States v. Classic, supra, 325-326. But according to the indictment they did not perform their duty. In an opinion written by Mr. Justice (later Chief Justice) Stone, in which Mr. Justice Roberts, Mr. Justice Reed, and Mr. Justice Frankfurter joined, the Court ruled, “Misuse of power, possessed by virtue of state law and made possible only because the wrongdoer is clothed with the authority of state law, is action taken ‘under color of’ state law.” Id., 326. There was a dissenting opinion; but the ruling as to the meaning of “under color of” state law was not questioned.

[24]That view of the meaning of the words “under color of” state law, 18 U.S.C. § 242, was reaffirmed in Screws v. United States, supra, 108-113. The acts there complained of were committed by state officers in performance of their duties, viz., making an arrest effective. It was urged there, as it is here, that “under color of” state law should not be construed to duplicate in federal law what was an offense under state law. Id. (dissenting opinion) 138-149, 157-161. It was said there, as it is here, that the ruling in the Classic case as to the meaning of “under color of” state law was not in focus and was ill-advised. Id. (dissenting opinion) 146-147. It was argued there, as it is here, that “under color of” state law included only action taken by officials pursuant to state law. Id. (dissenting opinion) 141-146. We rejected that view. Id., 110-113 (concurring opinion) 114-117. We stated:

“The construction given § 20 [18 U.S.C. § 242] in the Classic case formulated a rule of law which has become the basis of federal enforcement in this important field. The rule adopted in that case was formulated after mature consideration. It should be good for more than one day only.

[25]Mr. Shellabarger, reporting out the bill which became the Ku Klux Act, said of the provision with which we now deal:

“The model for it will be found in the second section of the act of April 9, 1866, known as the ‘civil rights act.’ … This section of this bill, on the same state of facts, not only provides a civil remedy for persons whose former condition may have been that of slaves, but also to all people where, under color of State law, they or any of them may be deprived of rights….”

Thus, it is beyond doubt that this phrase should be accorded the same construction in both statutes—in § 1979 and in 18 U.S.C. § 242.

[26]Since the Screws and Williams decisions, Congress has had several pieces of civil rights legislation before it. In 1956 one bill reached the floor of the House. This measure had at least one provision in it penalizing actions taken “under color of law or otherwise.” A vigorous minority report was filed attacking, inter alia, the words “or otherwise.” But not a word of criticism of the phrase “under color of” state law as previously construed by the Court is to be found in that report.

[27]Section 131(c) of the Act of September 9, 1957, 71 Stat. 634, 637, amended 42 U.S.C. § 1971 by adding a new subsection which provides that no person “whether acting under color of law or otherwise” shall intimidate any other person in voting as he chooses for federal officials. A vigorous minority report was filed attacking the wide scope of the new subsection by reason of the words “or otherwise.” It was said in that minority report that those words went far beyond what this Court had construed “under color of law” to mean. But there was not a word of criticism directed to the prior construction given by this Court to the words “under color of” law.

[28]The Act of May 6, 1960, 74 Stat. 86, uses “under color of” law in two contexts, once when § 306 defines “officer of election” and next when § 601 (a) gives a judicial remedy on behalf of a qualified voter denied the opportunity to register. Once again there was a Committee report containing minority views. Once again no one challenged the scope given by our prior decisions to the phrase “under color of” law.

[29]If the results of our construction of “under color of” law were as horrendous as now claimed, if they were as disruptive of our federal scheme as now urged, if they were such an unwarranted invasion of States’ rights as pretended, surely the voice of the opposition would have been heard in those Committee reports. Their silence and the new uses to which “under color of” law have recently been given reinforce our conclusion that our prior decisions were correct on this matter of construction.

[30]We conclude that the meaning given “under color of” law in the Classic case and in the Screws and Williams cases was the correct one; and we adhere to it.

[31]In the Screws case we dealt with a statute that imposed criminal penalties for acts “wilfully” done. We construed that word in its setting to mean the doing of an act with “a specific itent to deprive a person of a federal right.” 325 U.S., at 103. We do not think that gloss should be placed on § 1979 which we have here. The word “wilfully” does not appear in § 1979. Moreover, § 1979 provides a civil remedy, while in the Screws case we dealt with a criminal law challenged on the ground of vagueness. Section 1979 should be read against the background of tort liability that makes a man responsible for the natural consequences of his actions.

[32]So far, then, the complaint states a cause of action. There remains to consider only a defense peculiar to the City of Chicago.

* * * * *

Mr. Justice Harlan, whom Mr. Justice Stewart joins, concurring.

[33]Were this case here as one of first impression, I would find the “under color of any statute” issue very close indeed. However, in Classic and Screws this Court considered a substantially identical statutory phrase to have a meaning which, unless we now retreat from it, requires that issue to go for the petitioners here.

[34]From my point of view, the policy of stare decisis, as it should be applied in matters of statutory construction, and, to a lesser extent, the indications of congressional acceptance of this Court’s earlier interpretation, require that it appear beyond doubt from the legislative history of the 1871 statute that Classic and Screws misapprehended the meaning of the controlling provision, before a departure from what was decided in those cases would be justified. Since I can find no such justifying indication in that legislative history, I join the opinion of the Court. However, what has been written on both sides of the matter makes some additional observations appropriate.

[35]Those aspects of Congress’ purpose which are quite clear in the earlier congressional debates, as quoted by my Brothers Douglas and Frankfurter in turn, seem to me to be inherently ambiguous when applied to the case of an isolated abuse of state authority by an official. One can agree with the Court’s opinion that:

“It is abundantly clear that one reason the legislation was passed was to afford a federal right in federal courts because, by reason of prejudice, passion, neglect, intolerance or otherwise, state laws might not be enforced and the claims of citizens to the enjoyment of rights, privileges, and immunities guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment might be denied by the state agencies.”

without being certain that Congress meant to deal with anything other than abuses so recurrent as to amount to “custom, or usage.” One can agree with my Brother Frankfurter, in dissent, that Congress had no intention of taking over the whole field of ordinary state torts and crimes, without being certain that the enacting Congress would not have regarded actions by an official, made possible by his position, as far more serious than an ordinary state tort, and therefore as a matter of federal concern. If attention is directed at the rare specific references to isolated abuses of state authority, one finds them neither so clear nor so disproportionately divided between favoring the positions of the majority or the dissent as to make either position seem plainly correct.

[36]Besides the inconclusiveness I find in the legislative history, it seems to me by no means evident that a position favoring departure from Classic and Screws fits better that with which the enacting Congress was concerned than does the position the Court adopted 20 years ago. There are apparent incongruities in the view of the dissent which may be more easily reconciled in terms of the earlier holding in Classic.

[37]The dissent considers that the “under color of” provision of § 1983 distinguishes between unconstitutional actions taken without state authority, which only the State should remedy, and unconstitutional actions authorized by the State, which the Federal Act was to reach. If so, then the controlling difference for the enacting legislature must have been either that the state remedy was more adequate for unauthorized actions than for authorized ones or that there was, in some sense, greater harm from unconstitutional actions authorized by the full panoply of state power and approval than from unconstitutional actions not so authorized or acquiesced in by the State. I find less than compelling the evidence that either distinction was important to that Congress.

I.

[38]If the state remedy was considered adequate when the official’s unconstitutional act was unauthorized, why should it not be thought equally adequate when the unconstitutional act was authorized? For if one thing is very clear in the legislative history, it is that the Congress of 1871 was well aware that no action requiring state judicial enforcement could be taken in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment without that enforcement being declared void by this Court on direct review from the state courts. And presumably it must also have been understood that there would be Supreme Court review of the denial of a state damage remedy against an official on grounds of state authorization of the unconstitutional action. It therefore seems to me that the same state remedies would, with ultimate aid of Supreme Court review, furnish identical relief in the two situations.

* * * * *

[39]Since the suggested narrow construction of § 1983 presupposes that state measures were adequate to remedy unauthorized deprivations of constitutional rights and since the identical state relief could be obtained for state-authorized acts with the aid of Supreme Court review, this narrow construction would reduce the statute to having merely a jurisdictional function, shifting the load of federal supervision from the Supreme Court to the lower courts and providing a federal tribunal for fact findings in cases involving authorized action. Such a function could be justified on various grounds. It could, for example, be argued that the state courts would be less willing to find a constitutional violation in cases involving “authorized action” and that therefore the victim of such action would bear a greater burden in that he would more likely have to carry his case to this Court, and once here, might be bound by unfavorable state court findings. But the legislative debates do not disclose congressional concern about the burdens of litigation placed upon the victims of “authorized” constitutional violations contrasted to the victims of unauthorized violations. Neither did Congress indicate an interest in relieving the burden placed on this Court in reviewing such cases.

[40]The statute becomes more than a jurisdictional provision only if one attributes to the enacting legislature the view that a deprivation of a constitutional right is significantly different from and more serious than a violation of a state right and therefore deserves a different remedy even though the same act may constitute both a state tort and the deprivation of a constitutional right. This view, by no means unrealistic as a common-sense matter, [6] is, I believe, more consistent with the flavor of the legislative history than is a view that the primary purpose of the statute was to grant a lower court forum for fact findings. For example, the tone is surely one of overflowing protection of constitutional rights, and there is not a hint of concern about the administrative burden on the Supreme Court….

[41]Senator Carpenter reflected a similar belief that the protection granted by the statute was to be very different from the relief available on review of state proceedings:

“The prohibition in the old Constitution that no State should pass a law impairing the obligation of contracts was a negative prohibition laid upon the State. Congress was not authorized to interfere in case the State violated that provision. It is true that when private rights were affected by such a State law, and that was brought before the judiciary, either of the State or nation, it was the duty of the court to pronounce the act void; but there the matter ended. Under the present Constitution, however, in regard to those rights which are secured by the fourteenth amendment, they are not left as the right of the citizen in regard to laws impairing the obligation of contracts was left, to be disposed of by the courts as the cases should arise between man and man, but Congress is clothed with the affirmative power and jurisdiction to correct the evil.”

“I think there is one of the fundamental, one of the great, the tremendous revolutions effected in our Government by that article of the Constitution. It gives Congress affirmative power to protect the rights of the citizen, whereas before no such right was given to save the citizen from the violation of any of his rights by State Legislatures, and the only remedy was a judicial one when the case arose.”

Id., at 577.

In my view, these considerations put in serious doubt the conclusion that § 1983 was limited to state-authorized unconstitutional acts, on the premise that state remedies respecting them were considered less adequate than those available for unauthorized acts.

* * * * *

Mr. Justice Frankfurter, dissenting except insofar as the Court holds that this action cannot be maintained against the City of Chicago.

[42]Abstractly stated, this case concerns a matter of statutory construction. So stated, the problem before the Court is denuded of illuminating concreteness and thereby of its far-reaching significance for our federal system. Again abstractly stated, this matter of statutory construction is one upon which the Court has already passed. But it has done so under circumstances and in settings that negative those considerations of social policy upon which the doctrine of stare decisis, calling for the controlling application of prior statutory construction, rests.

* * * * *

[43]If the question whether due process forbids this kind of police invasion were before us in isolation, the answer would be quick. If, for example, petitioners had sought damages in the state courts of Illinois and if those courts had refused redress on the ground that the official character of the respondents clothed them with civil immunity, we would be faced with the sort of situation to which the language in the Wolf opinion was addressed: “we have no hesitation in saying that were a State affirmatively to sanction such police incursion into privacy it would run counter to the guaranty of the Fourteenth Amendment.” 338 U.S., at 28. If that issue is not reached in this case it is not because the conduct which the record here presents can be condoned. But by bringing their action in a Federal District Court petitioners cannot rest on the Fourteenth Amendment simpliciter. They invoke the protection of a specific statute by which Congress restricted federal judicial enforcement of its guarantees to particular enumerated circumstances. They must show not only that their constitutional rights have been infringed, but that they have been infringed “under color of [state] statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage,” as that phrase is used in the relevant congressional enactment.

* * * * *

[44]Insofar as the Court undertakes to demonstrate—as the bulk of its opinion seems to do—that § 1979 was meant to reach some instances of action not specifically authorized by the avowed, apparent, written law inscribed in the statute books of the States, the argument knocks at an open door. No one would or could deny this, for by its express terms the statute comprehends deprivations of federal rights under color of any “statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage” of a State. (Emphasis added.) The question is, what class of cases other than those involving state statute law were meant to be reached. And, with respect to this question, the Court’s conclusion is undermined by the very portions of the legislative debates which it cites. For surely the misconduct of individual municipal police officers, subject to the effective oversight of appropriate state administrative and judicial authorities, presents a situation which differs toto coelo from one in which “Immunity is given to crime, and the records of the public tribunals are searched in vain for any evidence of effective redress,” or in which murder rages while a State makes “no successful effort to bring the guilty to punishment or afford protection or redress,” or in which the “State courts … [are] unable to enforce the criminal laws … or to suppress the disorders existing,” or in which, in a State’s “judicial tribunals one class is unable to secure that enforcement of their rights and punishment for their infraction which is accorded to another,” or “of … hundreds of outrages … not one [is] punished,” or “the courts of the … States fail and refuse to do their duty in the punishment of offenders against the law,” or in which a “class of officers charged under the laws with their administration permanently and as a rule refuse to extend [their] protection.” These statements indicate that Congress‑made keenly aware by the post-bellum conditions in the South that States through their authorities could sanction offenses against the individual by settled practice which established state law as truly as written codes‑designed § 1979 to reach, as well, official conduct which, because engaged in “permanently and as a rule,” or “systematically,” came through acceptance by law-administering officers to constitute “custom, or usage” having the cast of law. See Nashville, C. & St. L. R. Co. v. Browning, 310 U.S. 362, 369. They do not indicate an attempt to reach, nor does the statute by its terms include, instances of acts in defiance of state law and which no settled state practice, no systematic pattern of official action or inaction, no “custom, or usage, of any State,” insulates from effective and adequate reparation by the State’s authorities.

[45]Rather, all the evidence converges to the conclusion that Congress by § 1979 created a civil liability enforceable in the federal courts only in instances of injury for which redress was barred in the state courts because some “statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage” sanctioned the grievance complained of. This purpose, manifested even by the so-called “Radical” Reconstruction Congress in 1871, accords with the presuppositions of our federal system. The jurisdiction which Article III of the Constitution conferred on the national judiciary reflected the assumption that the state courts, not the federal courts, would remain the primary guardians of that fundamental security of person and property which the long evolution of the common law had secured to one individual as against other individuals. The Fourteenth Amendment did not alter this basic aspect of our federalism.

* * * * *

[46]Relevant also are the effects upon the institution of federal constitutional adjudication of sustaining under § 1979 damage actions for relief against conduct allegedly violative of federal constitutional rights, but plainly violative of state law. Permitting such actions necessitates the immediate decision of federal constitutional issues despite the admitted availability of state-law remedies which would avoid those issues. This would make inroads, throughout a large area, upon the principle of federal judicial self-limitation which has become a significant instrument in the efficient functioning of the national judiciary. See Railroad Comm’n of Texas v. Pullman Co., 312 U.S. 496, and cases following. Self-limitation is not a matter of technical nicety, nor judicial timidity. It reflects the recognition that to no small degree the effectiveness of the legal order depends upon the infrequency with which it solves its problems by resorting to determinations of ultimate power. Especially is this true where the circumstances under which those ultimate determinations must be made are not conducive to the most mature deliberation and decision. If § 1979 is made a vehicle of constitutional litigation in cases where state officers have acted lawlessly at state law, difficult questions of the federal constitutionality of certain official practices—lawful perhaps in some States, unlawful in others—may be litigated between private parties without the participation of responsible state authorities which is obviously desirable to protect legitimate state interests, but also to better guide adjudication by competent recordmaking and argument.

[47]Of course, these last considerations would be irrelevant to our duty if Congress had demonstrably meant to reach by § 1979 activities like those of respondents in this case. But where it appears that Congress plainly did not have that understanding, respect for principles which this Court has long regarded as critical to the most effective functioning of our federalism should avoid extension of a statute beyond its manifest area of operation into applications which invite conflict with the administration of local policies. Such an extension makes the extreme limits of federal constitutional power a law to regulate the quotidian business of every traffic policeman, every registrar of elections, every city inspector or investigator, every clerk in every municipal licensing bureau in this country. The text of the statute, reinforced by its history, precludes such a reading.

[48]In concluding that police intrusion in violation of state law is not a wrong remediable under R.S. § 1979, the pressures which urge an opposite result are duly felt. The difficulties which confront private citizens who seek to vindicate in traditional common-law actions their state-created rights against lawless invasion of their privacy by local policemen are obvious, and obvious is the need for more effective modes of redress. The answer to these urgings must be regard for our federal system which presupposes a wide range of regional autonomy in the kinds of protection local residents receive. If various common-law concepts make it possible for a policeman—but no more possible for a policeman than for any individual hoodlum intruder—to escape without liability when he has vandalized a home, that is an evil. But, surely, its remedy devolves, in the first instance, on the States. Of course, if the States afford less protection against the police, as police, than against the hoodlum—if under authority of state “statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage” the police are specially shielded—§ 1979 provides a remedy which dismissal of petitioners’ complaint in the present case does not impair. Otherwise, the protection of the people from local delinquencies and shortcomings depends, as in general it must, upon the active consciences of state executives, legislators and judges. [7] Federal intervention, which must at best be limited to securing those minimal guarantees afforded by the evolving concepts of due process and equal protection, may in the long run do the individual a disservice by deflecting responsibility from the state lawmakers, who hold the power of providing a far more comprehensive scope of protection. Local society, also, may well be the loser, by relaxing its sense of responsibility and, indeed, perhaps resenting what may appear to it to be outside interference where local authority is ample and more appropriate to supply needed remedies.

[49]This is not to say that there may not exist today, as in 1871, needs which call for congressional legislation to protect the civil rights of individuals in the States. Strong contemporary assertions of these needs have been expressed. Report of the President’s Committee on Civil Rights, To Secure These Rights (1947); Chafee, Safeguarding Fundamental Human Rights: The Tasks of States and Nation, 27 GEO. WASH. L. REV. 519 (1959). But both the insistence of the needs and the delicacy of the issues involved in finding appropriate means for their satisfaction demonstrate that their demand is for legislative, not judicial, response. We cannot expect to create an effective means of protection for human liberties by torturing an 1871 statute to meet the problems of 1960.

* * * * *

![]() Monroe v. Pape – Audio and Transcript of Oral Argument

Monroe v. Pape – Audio and Transcript of Oral Argument

Footnotes

-

This section provides in material part: “The district courts shall have original jurisdiction of any civil action authorized by law to be commenced by any person: “(3) To redress the deprivation, under color of any State law, statute, ordinance, regulation, custom or usage, of any right, privilege or immunity secured by the Constitution of the United States or by any Act of Congress providing for equal rights of citizens or of all persons within the jurisdiction of the United States.” ↵

-

Subsection (a) provides: “The district courts shall have original jurisdiction of all civil actions wherein the matter in controversy exceeds the sum or value of $10,000, exclusive of interest and costs, and arises under the Constitution, laws, or treaties of the United States.” In their complaint, petitioners also invoked R.S. §§ 1980, 1981, 42 U.S.C. §§ 1985, 1986. Before this Court, however, petitioners have limited their claim to recovery to the liability imposed by § 1979. Accordingly, only that section is before us. ↵

-

Illinois Const., Art. II, § 6, provides:

“The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated; and no warrant shall issue without probable cause, supported by affidavit, particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.” Respondents also point to ILL. REV. STAT., c. 38, §§ 252, 449.1; Chicago, Illinois, Municipal Code, § 11-40. ↵

-

Id., p. 265. The speaker, Mr. Arthur of Kentucky, had no doubts as to the scope of § 1: “If the sheriff levy an execution, execute a writ, serve a summons, or make an arrest, all acting under a solemn, official oath, though as pure in duty as a saint and as immaculate as a seraph, for a mere error of judgment, [he is liable]” Ibid. (Italics added.) ↵

-

S. Rep. No. 1, 42d Cong., 1st Sess. ↵

-

There will be many cases in which the relief provided by the state to the victim of a use of state power which the state either did not or could not constitutionally authorize will be far less than what Congress may have thought would be fair reimbursement for deprivation of a constitutional right. I will venture only a few examples. There may be no damage remedy for the loss of voting rights or for the harm from psychological coercion leading to a confession. And what is the dollar value of the right to go to unsegregated schools? Even the remedy for such an unauthorized search and seizure as Monroe was allegedly subjected to may be only the nominal amount of damages to physical property allowable in an action for trespass to land. It would indeed be the purest coincidence if the state remedies for violations of common-law rights by private citizens were fully appropriate to redress those injuries which only a state official can cause and against which the Constitution provides protection. ↵

-

The common law seems still to retain sufficient flexibility to fashion adequate remedies for lawless intrusions. ↵

Notes on Monroe v. Pape

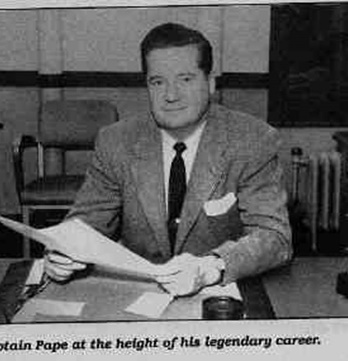

- For additional information about the characters, context and facts giving rise to Monroe v. Pape, see Giles, Police, Race and Crime in 1950s Chicago: Monroe v. Pape as Legal Noir, in CIVIL RIGHTS STORIES, (Myriam E. Giles and Risa L. Goluboff eds. 2008); CHARLES F. ADAMSON: THE TOUGHEST COPY IN AMERICA (2001); Charles F. Adamson, Pape’s Law, CHICAGO MAGAZINE (June 2000); Douglas Martin, Frank Pape, Celebrated Chicago Police Detective, Dies at 91, New York Times (March 12, 2000); Stephan Benzkofer, Legendary Lawmen, Part 6: Frank Pape, Chicago Tribune (January 1, 2012).

Mechanisms to Redress Violations of Federal Constitutional Rights

- Except for the just compensation clause of the Fifth Amendment, the United States Constitution does not explicitly provide for damages to redress constitutional violations. Do the following mechanisms afford adequate protection of constitutional rights?

- Criminal penalties against the official who violates the Constitution.

- Following the death of George Floyd, the Hennepin County district attorney charged Officer Derek Chauvin with third degree murder and manslaughter. After being asked by Minnesota Governor Tim Walz to lead the prosecution, the Minnesota Attorney General additionally charged Chauvin with Second Degree Murder—Unintentional—While Committing a Felony, with assault alleged as the underlying felony. The Attorney General also charged Officers Thao, Kueng, and Lane with one count of aiding and abetting a second-degree murder and one count of aiding and abetting second degree manslaughter.

- Professor Philip Stinson has compiled data on criminal arrest of nonfederal sworn law enforcement officers between 2005 and 2011/12. While approximately 1000 people are fatally shot by on-duty police officers, each year, 110 law enforcement officers were charged with murder or manslaughter over the period of Professor Stinson’s study. Fifty officers were acquitted. Of the 42 officers who were convicted on some counts, only five were found guilty of murder (18 cases are pending). See Why It’s So Rare For Police Officers To Face Legal Consequences

- Following the all-white jury’s acquittal of three police officers, and failure to reach a verdict against the fourth officer, in the state criminal trial arising out of the videotaped beating of Rodney King, the United States filed charges against the officers under 18 U.S.C § 242, which provides:

Whoever, under color of any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom, willfully subjects any person in any State, Territory, Commonwealth, Possession, or District to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured or protected by the Constitution or laws of the United States, or to different punishments, pains, or penalties, on account of such person being an alien, or by reason of his color, or race, than are prescribed for the punishment of citizens, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than one year, or both; and if bodily injury results from the acts committed in violation of this section or if such acts include the use, attempted use, or threatened use of a dangerous weapon, explosives, or fire, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than ten years, or both; and if death results from the acts committed in violation of this section or if such acts include kidnapping or an attempt to kidnap, aggravated sexual abuse, or an attempt to commit aggravated sexual abuse, or an attempt to kill, shall be fined under this title, or imprisoned for any term of years or for life, or both, or may be sentenced to death.

The racially mixed jury found Officers Koon and Powell guilty, and acquitted officers Wind and Briseno. For an in depth discussion of the two trials, see Professor Douglas Linder’s Famous Trials website.

- Federal statutes also impose criminal penalties for conspiracy to “injure, oppress, threaten, or intimidate” the exercise of a right secured by the Constitution (18 U.S.C. § 241); interference with prescribed federally protected activities, such as voting (18 U.S.C. § 245); intentionally damaging religious property based on the religious, ethnic, or racial characteristics of the property (18 U.S.C. § 247); interfering with an individual’s access to reproductive health services or places of worship I8 U.S.C. § 248); and hate crimes (18 U.S.C. § 249). The Congressional Research Service published an overview of these statutes.

- The exclusionary rule. In Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961), the United States Supreme Court overruled Wolf v. Colorado, 338 U.S. 25 (1949) and ruled that evidence obtained by searches and seizures in violation of the Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments to United States Constitution could not be admitted in a state criminal prosecution.

- Governmental actions for equitable relief.

- In the aftermath of the police beating of Rodney King, in 1994 Congress passed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act. 42 U.S.C. § 14141 provides:

- Unlawful conduct

It shall be unlawful for any governmental authority, or any agent thereof, or any person acting on behalf of a governmental authority, to engage in a pattern or practice of conduct by law enforcement officers or by officials or employees of any governmental agency with responsibility for the administration of juvenile justice or the incarceration of juveniles that deprives persons of rights, privileges, or immunities secured or protected by the Constitution or laws of the United States.

- Civil action by Attorney General

Whenever the Attorney General has reasonable cause to believe that a violation of paragraph (1) has occurred, the Attorney General, for or in the name of the United States, may in a civil action obtain appropriate equitable and declaratory relief to eliminate the pattern or practice.

- President Obama’s administration initiated pattern or practice investigations of 25 police department and entered into 14 consent decrees. Jeff Sessions, appointed as Attorney General by President Trump, dropped Obama era investigations into police departments in Chicago and Louisiana, alleging that consent decrees diminished morale among police officers and led to a rise in violent crime. On November 7, 2018, Attorney General Jeff Sessions issued a Memorandum prescribing a new internal Justice Department policy limiting the use of consent decrees and settlements against state and local governmental entities to where one or more of the following factors is present:

- The defendant has an established history of recalcitrance or is known to be unlikely to perform;

- The defendant has unlawfully attempted to obstruct the investigation;

- The defendant not only has engaged in a pattern or practice of deprivation rights, but in addition other remedies have proven ineffective, such that ensuring compliance without ongoing court supervision is unrealistic.

Memorandum at 4. The memorandum further required that senior leaders of the Department of Justice approve the consent decree or settlement, and limited the duration of consent decrees to three years, absent a compelling justification for a longer term, The memorandum set forth the following rationale for the limitations:

“[F]ederal court decrees that impose wide-ranging and long-term obligations on, or require ongoing federal supervision of, state and local governments are extraordinary remedies that “raise sensitive federalism concerns.” Such concerns are most acute when a federal judge … effectively superintends the ongoing operations of the government entity subject to the decree. This supervision can deprive the elected representatives of the people of the affected jurisdiction of control of their government. Consent decrees can also have significant ramifications for state or local budget priorities, effectively taking these decisions, and accountability for them, away from the people’s elected representatives.” Memorandum at 2 (citations omitted).

Attorney General William Barr, who succeeded Jeff Sessions, endorsed the principles in Sessions’ memo in Supplementary Information published in the Federal Register accompanying a final rule amending the Regulations of the Department of Justice regarding procedures for approving consent decrees in civil actions against state or local governmental entities. The new approval procedures were codified in 28 C.F.R. §0.160(d)(6). On April 16, 2021, President Biden’s Attorney General Merrick Garland issued a Memorandum rescinding Sessions’ November 2018 Memorandum Regarding Settlement Agreements and Consent Decrees and ordered withdrawal of the provisions of the United States Department of Justice Manual incorporating the November 2018 Memorandum. Attorney General Garland further directed the initiation of processes to revise the amendment to 28 C.F.R. §§ 0.160(d)(6)-(e) that Attorney General Barr had effectuated.

Attorney General Garland’s April 16, 2021 Memorandum noted that Congress had “authorized the Department of Justice to file lawsuits against state and local governmental entities to obtain legal and equitable relief to remedy violation of federal law,” and that “we will continue the Department’s legacy of promoting the rule of law, protecting the public, and working collaboratively with state and local governmental entities to meet those ends.” Memorandum, at 1, 4. On April 21, 2021, General Garland announced that in addition to its previously opened federal criminal investigation into the death of George Floyd, the Department of Justice had initiated a pattern or practice investigation into the City of Minneapolis and the Minneapolis Police Department’s use of force; discriminatory policing; the Police Department’s policies training, and supervision; and the Police Department’s “systems of accountability, including complaint intake, investigation, review, disposition, and discipline.” In announcing the investigation, Attorney General Garland noted:

Yesterday’s verdict in the state criminal trial [finding Officer Derek Chauvin guilty of second-and third-degree murder as well as second degree manslaughter in the death of George Floyd] does not address potential systemic policing issues in Minneapolis.

* * * *

If the Justice Department concludes that there is reasonable cause to believe there is a pattern or practice of unconstitutional or unlawful policing, we will issue a report of our conclusions.

The Justice Department also has the authority to bring a civil lawsuit asking a federal court to provide injunctive relief that orders the MPD [Minneapolis Police Department]to change its policies and practices to avoid further violations.

Usually, when the Justice Department finds unlawful patterns or practices, the local police department enters into a settlement agreement or a consent decree to ensure that prompt and effective action is taken to align policing practices with the law.

Most of our nation’s law enforcement officers do their difficult jobs honorably and lawfully.

I strongly believe that good officers do not want to work in systems that allow bad practices. Good officers welcome accountability because accountability is an essential part of building trust with the community and public safety requires public trust.

On April, 26, 2021, Attorney General Garland announced an investigation into the Louisville/Jefferson County Metro Government and the Louisville Metro Police Department to determine whether the Department engages in a pattern or practice of using unreasonable force; engages in unconstitutional stops, searches, and seizures and unlawfully executes search warrants on private homes; engages in discriminatory conduct on the basis of race; or fails to provide public services that comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act. And on August 5, 2021, the Justice Department announced it would open an investigation to determine whether the officers of the Phoenix Police Department discriminate against minorities; use excessive force or retaliate against peaceful protestors; or mistreat the homeless and the disabled.

- Following the release of a video of the shooting of Laquan McDonald, a black teenager, 16 times by a white officer, Jason VanDyke, the United States Department of Justice as well as the Mayor of Chicago’s Police Accountability Task Force investigated and made recommendations in response to allegations that the Chicago Police Department engages in a pattern and practice of civil rights violations and unconstitutional policing. The Attorney General of the State of Illinois then filed a civil action in federal court against the City of Chicago under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, the Illinois Constitution, the Illinois Civil Rights Act of 2003, and the Illinois Human Rights Act. The Complaint alleged that the Department had engaged in a pattern of using excessive force, including deadly force, disproportionately harming the City’s black and Latinx residents. The State and the City entered into a 286-page Consent Decree requiring changes to the policies and operations of the Chicago Police Department, the Civilian Office of Police Accountability, and the Police Board. The Consent Decree provided for an independent monitor to assess and report on “whether the requirements of this Agreement have been implemented, and whether implementation is resulting in constitutional policing and increased community trust of the CPD [Chicago Police Department].” Consent Decree, paragraph 610. The United States Department of Justice filed a Statement of Interest Opposing approval of the Consent Decree. https://www.justice.gov/opa/press-release/file/1100631/ download. See also Jason Mazzone and Stephen Rushin, State Attorneys General As Agents of Police Reform, 69 DUKE L.J. 999 (2020).

- Is a damage remedy an appropriate mechanism to ensure that government and its officials do not disregard individual liberties guaranteed by the Constitution?

- In light of the similarities between the goals (deterrence) and mechanisms (cost-internalization) of private law damages and constitutional cost remedies, perhaps it should come as no surprise that courts and commentators have routinely applied conventional assumptions about the behavior of firms in market environments to government behavior. Discussions of constitutional cost remedies usually start from the assumption that the incentive effects of cost-internalization will be the same for government as for private firms and that cost-benefit analysis by government decisionmakers will result in socially optimal choices about activities that threaten constitutional rights. Courts and commentators usually take for granted that government will respond to cost-internalization more or less like a corporation, so that requiring government to compensate the victims of takings or constitutional torts ensures that government will take full account of the costs of its actions. If the government does not respond to costs and benefits in the same way as a private firm, however, then none of these predictions about the instrumental effects of constitutional cost remedies on government behavior is likely to be accurate. In fact, for reasons that are elaborated below, there is every reason to expect government to behave quite differently from private firms. Because government actors respond to political, not market, incentives, we should not assume that government will internalize social costs just because it is forced to make a budgetary outlay. They only way to predict the effects of constitutional cost remedies is to convert the financial costs they impose into political costs. This may be possible, but only by constructing models of government decision making that are capable of exchanging economic costs and benefits into political currency. As this Article goes on to demonstrate, any such model will be highly contextual, complex, and controversial. Daryl J. Levinson Making Government Pay: Markets, Politics, and the Allocation of Constitutional Costs, 67 U. CHI. L. REV. 345, 347 (2000).

- For those who accept the desirability of constitutional change, the right- remedy gap has a silver lining. Put simply, the limitations on money damages for constitutional violations facilitate constitutional change. The doctrines that deny full individual remediation reduce the cost of innovation, thereby advancing the growth and development of constitutional law. If constitutional tort doctrine were reformed to assure full remediation, the costs of compensation would constrict the future of constitutional law. John C. Jeffries, Jr., The Right-Remedy Gap in Constitutional Law, 109 YALE L.J. 87, 98 (1999).

- [F]ar from having a uniformly negative influence on courts’ willingness to expand rights, constitutional tort actions have shifted courts’ attention to the injury suffered by individuals. In doing so, they have influenced courts to establish constitutional rights that protect individuals from governmental injury and regulate the government’s power to inflict harm. The current concept of individual harm is an integral part of many constitutional rights. Rather than having a wholly negative effect on the reach of constitutional rights, the constitutional tort remedy contributes to a broader process of rights definition where abstract constitutional provisions are translated into terms relevant to the injuries of individuals. James J. Park, The Constitutional Tort Action as Individual Remedy, 38 HARV. C.R.-C.L. L. REV. 393, 419 (2003).

- In Binette v. Sabo, 710 A.2d 688 (Conn. 1980), plaintiffs alleged the City of Torrington police chief and a city police officer entered their home without a warrant, and then pushed and struck the plaintiffs. Plaintiffs filed a civil action seeking compensatory and punitive damages for the officers’ violation of plaintiffs’ rights under the Connecticut Constitution. The Connecticut Supreme Court held that even though the state legislature had not authorized a civil action for deprivation of rights secured by the state constitution, plaintiffs could recover damages caused by the officers’ violation of the state charter. The Supreme Court rejected defendants’ assertion that because plaintiffs had a remedy under state tort law, the court should refuse to create a damage action for infringement of rights guaranteed by the state constitution:

[W]e agree with the fundamental principle underlying the United States Supreme Court’s decision in Bivens, namely, that a police officer acting unlawfully in the name of the state “possesses a far greater capacity for harm than an individual trespasser exercising no authority other than his own.” Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents of Federal Bureau of Narcotics, supra, 403 U.S. 392; see id., 409 (Harlan, J., concurring) (“the injuries inflicted by officials acting under color of law … are substantially different in kind [from those inflicted by private parties]”). The difference in the nature of the harm arising from a beating administered by a police officer or from an officer’s unconstitutional invasion of a person’s home, on the one hand, and an assault or trespass committed against one private citizen by another, on the other hand, stems from the fundamental difference in the nature of the two sets of relationships. A private citizen generally is obliged only to respect the privacy rights of others and, therefore, to refrain from engaging in assaultive conduct or from intruding, uninvited, into another’s residence. A police officer’s legal obligation, however, extends far beyond that of his or her fellow citizens: the officer not only is required to respect the rights of other citizens, but is sworn to protect and defend those rights. In order to discharge that considerable responsibility, he or she is vested with extraordinary authority. Consequently, when a law enforcement officer, acting with the apparent imprimatur of the state, not only fails to protect a citizen’s rights but affirmatively violates those rights, it is manifest that such an abuse of authority, with its concomitant breach of trust, is likely to have a different, and even more harmful, emotional and psychological effect on the aggrieved citizen than that resulting from the tortious conduct of a private citizen.

Binette, 710 A.2d at 698.

The Appropriate Forum for Adjudication of Constitutional Rights

- Does the background to Section 1983 demand or justify a disregard of traditional federalism notions? Are the concerns of the enacting Congress valid today?

- In Jamison v. McClendon, No, 3:16-CV-595-CWR-LRA (S.D. Miss. August 4, 2020), District Judge Reeves starkly recounted the actions on the ground following passage of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution that gave rise to enactment of Section 1983:

“In Mississippi, it became a criminal offense for blacks to hunt or fish,” and a U.S. Army General reported that “white militias, with telltale names such as the Jeff Davis Guards, were springing up across” the state. In Shreveport, Louisiana, more than 2,000 black people were killed in 1865 alone. “In 1866, there were riots in Memphis and New Orleans; more than 30 African-Americans were murdered in each melee.”

The Ku Klux Klan, formed in 1866 by six white men in a Pulaski, Tennessee law office, ‘engaged in extreme violence against freed slaves and Republicans,’ assaulting and murdering its victims and destroying their property.” The Klan “spread rapidly across the South” in 1868, orchestrating a “huge wave of murder and arson” to discourage Blacks from voting. “[B]lack schools and churches were burned with impunity in North Carolina, Mississippi, and Alabama.”

The terrorism in Mississippi was unparalleled. During the first three months of 1870, 63 Black Mississippians “were murdered … and nobody served a day for these crimes.” In 1872, the U.S. Attorney for Mississippi wrote that Klan violence was ubiquitous and that “only the presence of the army kept the Klan from overrunning north Mississippi completely.

Many of the perpetrators of racial terror were members of law enforcement. It was a twisted law enforcement, though, as it prevented the laws of the era from being enforced. When the Klan murdered five witnesses in a pending case, one of Mississippi’s District Attorneys complained, “I cannot get witnesses as all feel it is sure death to testify.” White supremacists and the Klan “threatened to unravel everything … Union soldiers had accomplished at great cost in blood and treasure.”

Professor Leon Litwack described the state of affairs in stark words:

How many black men and women were beaten, flogged, mutilated, and murdered in the first years of emancipation will never be known. Nor could any accurate body count or statistical breakdown reveal the barbaric savagery and de pravity that so frequently characterized the assaults made on freedmen in the name of restraining their savagery and depravity—the severed ears and entrails, the mutilated sex organs, the burnings at the stake, the forced drownings, the open display of skulls and severed limbs as trophies.

- The United States Supreme Court expressly recognized that the legislative history of Section 1983:

[m]akes evident that Congress clearly conceived that it was altering the relationship between the States and the Nation with respect to the protection of federally created rights; it was concerned that state instrumentalities could not protect those rights; it realized that state officials might, in fact, be antipathetic to the vindication of those rights; and it believed that these failings extended to the state courts.

Section 1983 was thus a product of a vast transformation from the concepts of federalism that had prevailed in the late 18th century when the anti-injunction statue was enacted. The very purpose of §1983 was to interpose the federal courts between the States and the people, as guardians of the people’s federal rights—to protect the people from unconstitutional action under color of state law, “whether that action be executive, legislative, or judicial.”

Mitchum v. Foster, 407 U.S. 225, 242 (1972) (§1983 is an “expressly authorized” exception to statute [28 U.S.C. §2283] barring federal court injunction to stay proceedings in state court).

- In Patsy v. Board of Regents, 457 U.S. 496, 503-07 (1982), the Court relied upon the 1871 legislature’s view of the appropriate forum for adjudication of federal constitutional rights in holding that a Section 1983 plaintiff is not generally required to exhaust state administrative remedies:

At least three recurring themes in the debates over §1 cast doubt on the suggestion that requiring exhaustion of state administrative remedies would be consistent with the intent of the 1871 Congress. First, in passing §1, Congress assigned to the federal courts a paramount role in protecting constitutional rights.

*****

A second theme in the debates further suggests that the 1871 Congress would not have wanted to impose an exhaustion requirement. A major factor motivating the expansion of federal jurisdiction through §§1 and 2 of the bill was the belief of the 1871 Congress that the state authorities had been unable or unwilling to protect the constitutional rights of individuals or to punish those who violated those rights.

*****

A third feature of the debates relevant to the exhaustion question is the fact that many legislators interpreted the bill to provide dual or concurrent forums in the state and federal system, enabling the plaintiff to choose the forum in which to seek relief.

But see Prison Litigation Reform Act of 1995, 42 U.S.C. §1997e (“No action shall be brought with respect to prison conditions under [§1983] . . . by a prisoner confined in any jail, prison, or other correctional facility until such administrative procedures as are available are exhausted.”); Heck v. Humphrey, 512 U.S. 477, 486-87 (1994) (“[I]n order to recover damages for allegedly unconstitutional conviction or imprisonment, or for other harm caused by actions whose unlawfulness would render a conviction or sentence invalid, a Section 1983 plaintiff must prove that the conviction has been reversed on direct appeal, expunged by executive order, declared invalid by a state tribunal authorized to make such a determination, or called into question by a federal court’s issuance of a writ of habeas corpus. . . . “).

- Former Supreme Court Justice Blackmun has expressed wariness over invoking traditional federalism concerns to limit the role Section 1983 plays in vindicating constitutional rights:

In my view, any plan to restrict the scope of § 1983 comes with a heavy burden of justification—a burden that is both constitutional and historical. The constitutional burden is the need to demonstrate that the interests of federalism, comity, or judicial efficiency can be advanced without sacrificing protection for our constitutional rights. If increased state autonomy and reduced federal caseloads can be purchased only with the coin of more constitutional violations and fewer constitutional remedies, the price is high and is one I am not prepared to pay. Nor is it one, by the way, that critics of § 1983 usually attempt to justify.

The historical burden is the need to show, in light of the systematic disregard of civil rights by state governments and state courts that led to the original Civil Rights Acts, that constitutional claims can safely be committed to state courts, not only for the present but for the future. It is no reflection on the current good faith of state governments and state courts to observe that history is not a one-way street. While we all can work to prevent a return to the judicial indifference and paralysis of the past, none of us can guarantee that the day will not return when a litigant who cannot vindicate his constitutional rights in federal court will not be able to vindicate them at all. If that day should come, it will be far harder to reconstruct a statutory remedy that has been judicially interred or legislatively undone in the meantime than it would be to resort to a remedy that has been intact and working in the intervening years. In short, once we restrict the role of federal courts in protecting constitutional rights, we may find ourselves hard pressed to recover what has been given up.

* * * * *

When the Fourteenth Amendment became part of the Constitution, it committed this Nation to an order in which all governments, state as well as federal, were bound to respect the fundamental rights of individuals. That commitment, too, is a part of “Our Federalism,” no less than the values of state autonomy than the critics of § 1983 so passionately invoke on.

Hon. Harry A. Blackmun, Section 1983 and Federal Protection of Individual Rights—Will the Statute Remain Alive or Fade Away? 60 N.Y.U. L. REV. 1, 28 (1985).

- Contrary to the cautions expressed by Justice Blackmun, Justice O’Connor has suggested that state courts should no longer be saddled by the distrust accorded when the federal remedy for constitutional violations was enacted.

State courts will undoubtedly continue in the future to litigate federal constitutional questions. State judges in assuming office take an oath to support the federal as well as the state constitution. State judges do in fact rise to the occasion when given the responsibility and opportunity to do so. It is a step in the right direction to defer to the state courts and give finality to their judgments on federal constitution questions where a full and fair adjudication has been given in the state court.

* * * * *

Proposals are sometimes made to restrict federal court jurisdiction over certain types of cases or issues. Among the proposals which have merit from the perspective of a state court judge are … a requirement of exhaustion of state remedies as a prerequisite to bringing a federal action under Section 1983. If we are serious about strengthening our state courts and improving their capacity to deal with federal constitutional causes, then we will not allow a race to the courthouse to determine whether another will be heard first in the federal or state court. We should allow the state courts to rule first on the constitutionality of state statutes.

Hon. Sandra Day O’Connor, Trends in the Relationship Between the Federal and State Courts from the Perspective of a State Court Judge, 22 WM. & MARY L. REV. 801, 814-815 (1981) (emphasis in original). See also Ruggero J. Aldisert, State Courts and Federalism in the 1980’s, 22 WM. & MARY L. REV. 821 (1981).

- An empirical study compared the disposition of federal constitutional issues by federal and state courts. Michael E. Solimine and James L. Walker, Constitutional Litigation in Federal and State Courts: An Empirical Analysis of Judicial Parity, 10 HASTINGS CONST. L.Q. 213 (1983). The authors evaluated a random sampling of reported decisions of federal district courts and state appellate and supreme courts for the years 1974 through 1980 involving claims based upon the First and Fourteenth Amendments and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The study generated the following data:

Results of All Cases

Category Percent Claim Upheld 36% Claim Denied 64% Outcome Versus Forum by Case Type

Court

Claim Upheld

Claim Denied

Federal Court

41%

59%

State Court

32%

68%

Outcome Versus Forum by Case Type

Court

Civil Cases Upheld

Civil Cases Denied

Criminal Cases Upheld

Criminal Cases Denied

Federal Court

44.6%

55.4%

33.9%

66.1%

State Court

33.2%

66.8%

30.5%

69.5%

Id. at 239-42. Did the study examine a proper sampling of cases? See Kevin M. Clermont and Theodore W. Eisenberg, Plaintiphobia in the Appellate Courts: Civil Rights Really Do Differ From Negotiable Instruments, 2002 U. ILL. L. Rev. 947 (2002) (concluding that defendants are much more likely than plaintiffs to obtain reversal on appeal after trial in civil rights cases due to anti-plaintiff appellate bias). What do the results indicate with respect to the litigation of federal constitutional claims in state as opposed to federal courts?