3.3 Glomar Challenger

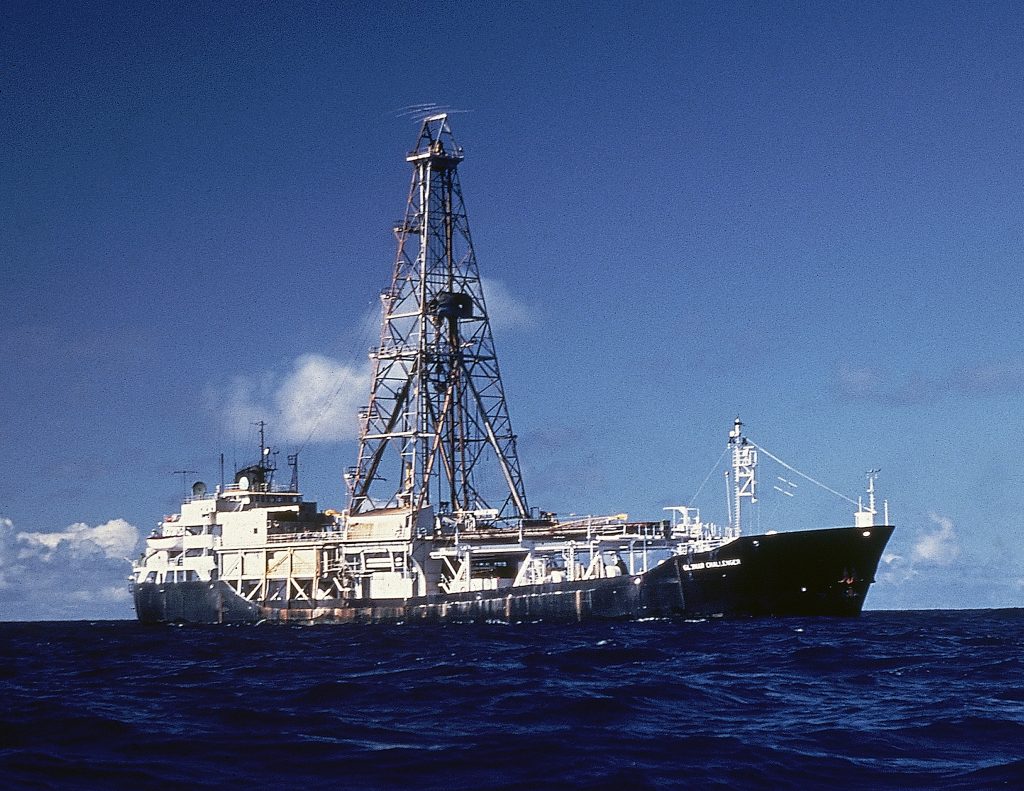

The Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP, 1968–1983) was a 15-year program that explored the sediments on the ocean floor and the upper part of the underlying crust. With a newly-built scientific ocean drilling vessel Glomar Challenger, the DSDP program completed 96 expeditions and recovered cores from 624 sites throughout the ocean, providing >97,000 meters of core material for scientists to study Earth’s deep-ocean environments. DSDP was the first of multiple international scientific ocean drilling programs that have operated for decades.

These maps show the drill site locations from the Deep Sea Drilling Project. Maps are available from IODP JRSO.

World map showing locations of DSDP Legs 1–96, Sites 1–624, across all ocean basins. Image 1: Sites labeled. Image 2: Color map. (Credit: Drill Site Maps, IODP JRSO, CC BY 4.0)

“Unquestionably … the largest and most successful program of geological investigation ever undertaken by man.” (Emiliani, 1981, p. 1705, referring to DSDP)

A film was produced in 1974 capturing the work of Glomar Challenger. This 30-minute film not only shows the ship technology available at the time but the thinking of seafloor spreading and paleomagnetics during the National Science Foundation-funded Deep Sea Drilling Project. Additional film details are available at archive.org.

Exercise: Overview of the Deep Sea Drilling Project

After viewing the video “Deep Sea Drilling Project” above, how would you respond to the following questions:

a) What were the early questions scientists were trying to answer through the Deep Sea Drilling Project?

b) How did Glomar Challenger know its position? And how was it able to stay in position during the drilling activities?

DSDP Leg 1 – The First Drilling Report

Upon the conclusion of each DSDP Leg, a print publication was released titled Initial Reports of the Deep Sea Drilling Project. The reports contained the results of initial studies of the recovered core material and the associated geophysical information from each expedition.

The first DSDP Leg immediately yielded important results. At the second Site, core material showed the existence of salt domes at a depth of 1,067 meters, a discovery of great interest to oil companies and for economic development. This discovery and more were written up and published in Volume 1 of the Initial Reports series.

A book review was written by Tjeered Van Andel about this first volume and published in the journal Science. Titled “Results of a Program in Oceanography”, the review states that this volume “…covers the results of the first of these cruises, a period of learning and experimentation, no doubt, but nevertheless rich in results of great importance.” The volume is described as “a Sears Roebuck catalog of tempting sedimentary material, documented by massive tables and graphs designed primarily to inform the reader about the material available for further study. Approximately 500 of the 672 pages are devoted exclusively to this purpose.”

Copies of all Initial Reports of the Deep Sea Drilling Project, Leg 1 through Leg 96, can be found online.

DSDP Leg 2 – The First Women Sail

Bonatti and Crane (2012) published an excellent overview of Oceanography and Women: Early Challenges, starting with the ancient taboos that prevented women scientists from sailing on oceanographic vessels until roughly the mid-1960s. Although female French botanist Jeanne Baret was the first woman to sail around the world in 1676-1679, she boarded the ship disguised as a man and was successful at maintaining her cover for over a year. The H.M.S. Challenger expedition (1872-1876, see this OER chapter), with over 240 scientists and crew, did not have any women on board.

Fast-forward to the start of the Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP) and its first expedition in August-September 1968. No women participated on board Glomar Challenger for Leg 1, but the first two women to sail on Glomar Challenger joined during Leg 2 – Dr. Maria Cita (paleontologist, Universita di Milano, Italy) and Dr. Catherine Nigrini (paleontologist, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, USA). Leg 2 started from Hoboken, New Jersey, and ended in Dakar, Senegal (October-November, 1968).

No women were present again on Glomar Challenger until almost a year later for Leg 7, when Dr. Johanna Resig (paleontologist, University of Hawaii, HI) and Dr. Elizabeth Gealy (Scripps Institution of Oceanography, CA) joined the ship August-September 1969.

SciOD Spotlight – Dr. Elizabeth “Betty” Gealy

Elizabeth “Betty” Gealy was born in Texas in 1923 as the daughter of a prospector who drilled exploratory oil wells. She earned bachelors degrees in art and geology from Southern Methodist University and a M.A. and Ph.D. in geology from Harvard University (her degrees are technically from Radcliffe College, which had a joint enrollment program with Harvard since Harvard did not award degrees to women in the early 1950s).

Her journey as a geologist was not an easy one. When she applied for her first professional geology job in the 1940s, she was hired as a secretary by Humble Oil & Refining until she was promoted to a staff geologist. When she attended Harvard for graduate school, one of her professors told her that he was required to allow her in his class, but he was not required to pass her. Betty ended up graduating Harvard Phi Beta Kappa.

Dr. Gealy joined Scripps Institution of Oceanography in 1967 to manage the scientific ocean drilling program. She was one of the few females of her time to be in such a high-profile scientific position. Betty authored History and Evaluation of the Logging Program of the Deep Sea Drilling Project Through May, 1969 and was the lead author on Special Papers: Results of the Joides Deep Sea Drilling Project; 1968-1971. She departed Scripps in the early 1970s and passed away in 2009.

DSDP Leg 3 – Plate Tectonics

Glomar Challenger carried out 96 expeditions, but it is the third expedition (Leg 3, December 1968 to January 1969) that stands out as one of the most significant in scientific ocean drilling history. Leg 3 took place in the equatorial and South Atlantic Ocean, drilling 17 holes at 10 sites. This expedition set out to verify the theories of seafloor spreading and plate tectonics through investigating the tectonic development of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge (the structure and movement of oceanic crust) and examining the history of sedimentation in the South Atlantic Ocean. Scientists were able to confirm these theories and learn much more.

But the South Atlantic Ocean has not been sampled or studied much, compared to other ocean basins. So in 2022, IODP Expeditions 390/393 returned to the same region to collect new samples, to perform analyses with new equipment, and to ask new research questions on topics the scientists on Glomar Challenger would never have known to investigate.

Comparison of drilling location maps for scientific ocean drilling expeditions. Image 1: Site map for DSDP Leg 3. Image 2: Site map for Expeditions 390 and 393, which revisited the region of DSDP to collect samples roughly 50 years later. (Credit: DSDP Volume III – Introduction, and Expedition 390/393 Summary from the Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program Volume 390/393, IODP JRSO, CC BY 4.0)

“Without a detailed knowledge of the past, the present cannot be understood and the future cannot be predicted.” (Emiliani, 1981, p. 1705)

Glomar Challenger retires, but the legacy continues

Glomar Challenger started and ended its career with the Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP) in the Gulf of Mexico. Starting with Leg 1 (August-September 1968) and ending with Leg 96 (September-November 1983), this ship played a critical role in DSDP attaining its overarching goal of gathering scientific information that would help determine the age and processes of development of the ocean basins through the drilling of deep holes in the ocean. Upon its retirement, a logo was made to commemorate Glomar Challenger.

Core material collected by Glomar Challenger is still available to scientists today through one of the three international core repositories: Gulf Coast Repository (Texas, USA); Bremen Core Repository (Germany); and, Kochi Core Center (Japan).

As for the ship itself… after docking for the final time, Glomar Challenger was scrapped. Yet parts of the ship are in the physical archives at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC (see the image gallery below).

Items from Glomar Challenger in the archives of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History (Washington DC). Image #1: Hydrophone head; Image #2: Steering stand; Image #3: Engine power stand; Image #4: Propeller-shaft skeg. (Credit: Smithsonian Learning Lab, CC0 1.0)

References

Bonatti, E., and K. Crane. (2012). Oceanography and women: Early challenges. Oceanography 25(4):32–39, https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2012.103.

Emiliani, C. (1981). A new global geology. In: Emiliani, C. (editor). The Oceanic Lithosphere, The Sea, Vol. 7, 1685-1716. ISBN 0471028703

Citation for group image: Deep Sea Drilling Project, “Deep Sea Scientists-Three scientists examine a worn-out drill bit, which was used on the second leg of the Deep Sea Drilling Project. Left to right, Maria Bianca Cita, of Milan Italy; Elizabeth Lee Gealy, of Scripps Institution of Oceanography; and Catherine Nigrini, of Toronto, Canada. Cita and Nigrini were scientific staff for the Second DSDP Leg – New York to Dakar. Gealy was Executive Staff Geologist for DSDP at SIO. 1968.”, 1968, Scripps Institution of Oceanography Photographs, UC San Diego Library), https://library.ucsd.edu/dc/object/bb9796352p

Citation for SciOD image: creator, “DSDP Staff Geologist – Dr. Betty Gealy, of Richardson, Texas, Executive Staff Geologist for the Deep Sea Drilling Project, measures ocean bottom sediment with the aid of a penetrometer. Scripps Institution of Oceanography of the University of California at San Diego is operating institution for the $12.6 million project which is a part of the National Science Foundation’s National Research Program of Ocean Sediment Coring”, 1968-03-25, Scripps Institution of Oceanography Photographs, UC San Diego Library, https://library.ucsd.edu/dc/object/bb2867959f

DSDP Leg 3 location site map from the Introduction of the Initial Reports of the Deep Sea Drilling Project Volume III. IODP Expedition 390/393 site map from the drilling location maps included with IODP Proceedings Volume 390/393.

[Text on this page was adapted from JR EXP 390 blog posts The Ships that Sailed Before Us and DSDP Leg 3 and Dr. Elizabeth “Betty” Gealy]