2.6 JOIDES Institutions Assemble

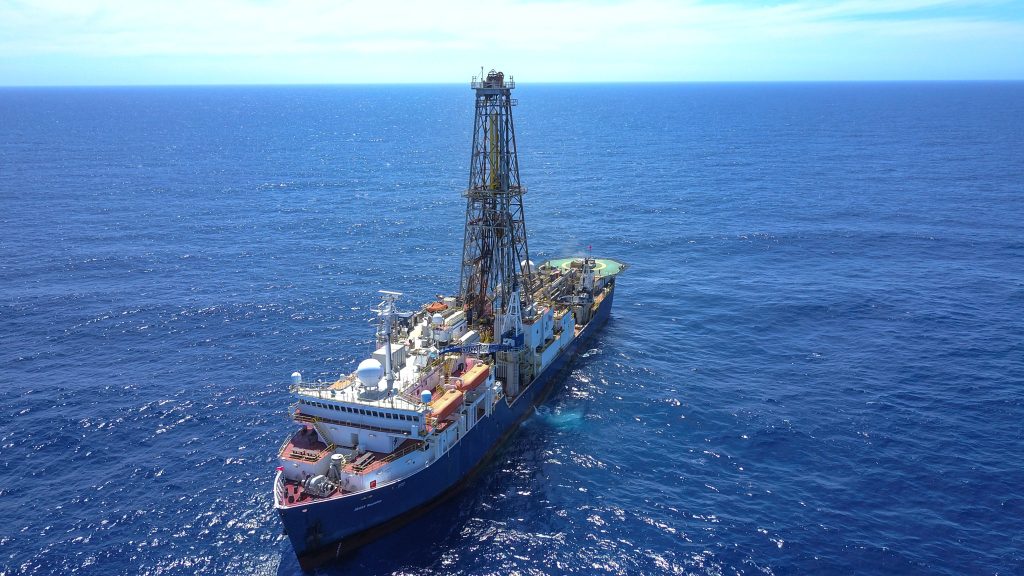

Note that the content on this page pertains to the group of institutions that formed JOIDES (Joint Oceanographic Institutions Deep Earth Sampling), not to the scientific drilling vessel pictured above. The drill ship was named in 1985 in honor of the JOIDES organization.

And you may see a small difference in what JOIDES stands for. Originally, JOIDES was defined as the abbreviation for Joint Oceanographic Institutions Deep Earth Sampling. In 1975, when the first JOIDES office was established at the Lamont-Doherty Geological Observatory, the word “for” was inserted yet the acronym did not change. Moving forward, JOIDES represented the Joint Oceanographic Institutions for Deep Earth Sampling.

With the conclusion of Project Mohole, U.S. scientists had not only scientific but financial challenges to find a path forward. Fortunately, scientists continued with their pursuit to collect materials from below the seafloor for basic discovery and testing of hypotheses to understand fundamental Earth systems and processes. These efforts provided the foundation for today’s scientific drilling activities, where the international community is advancing our understanding of Earth’s climate history, structure, dynamics, and deep biosphere, as well as addressing societally-relevant questions.

JOIDES Organizes

For several years after the conclusion of Project Mohole, scientists made formal and informal proposals to the National Science Foundation for sedimentary drilling projects. In the fall of 1963, in Congressional testimony, the National Science Foundation proposed an Ocean Sediment Coring Program that would be different from Project Mohole and “intended to increase man’s knowledge of the history, age, and structure of the ocean basins and the evolution of marine life. The program objective is to be accomplished by the scientific analyses of samples of sediments obtained by into the floors of the oceans” (National Science Foundation, 1972).

In May 1964, four major oceanographic institutions with strong marine geology and geophysics programs came together to form JOIDES (Joint Oceanographic Institutions Deep Earth Sampling). The purpose of JOIDES was to move these institutions forward through cooperative efforts “to promote the investigation of the ocean floor through the laboratory examination of samples from considerable depths beneath the ocean floor” (JOIDES, 1967). The group established committees for administrative procedures, for formulating basic policy, to ensure equal distribution of samples to U.S. scientists, and to collect information for possible future drilling sites.

M/V Caldrill I

The JOIDES Planning Committee initially targeted areas along the coasts of North and Central America with water depths of less than 2,000 meters. Their strategy was to limit their focus to these regions before taking on the greater challenges of deep-sea sampling.

But in the spring of 1965, a unique opportunity fast-tracked their mission. The Pan American Petroleum Corporation, an American oil company, offered the use of its drilling vessel, the M/V Caldrill I, which was scheduled to travel from California to the Atlantic to drill a series of holes on the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. With about a month of downtime along the way, Pan American agreed to cover the Caldrill’s transit costs, allowing JOIDES to utilize the vessel for scientific drilling on their route to Newfoundland.

With this unexpected resource at their disposal, the team selected the Blake Plateau, located off Jacksonville, Florida, as the test drilling site. The National Science Foundation (NSF) provided $250,000 from its regular research funds, allowing Lamont Geological Observatory to conduct a one-month drilling program in April and May 1965.

During this period, the Caldrill I, equipped with dynamic positioning, drilled six holes at water depths ranging from 25 to 1,032 meters and achieved drilling depths between 120 and 320 meters. Core recovery averaged 36%, and samples were sent to the University of Miami for analysis, resulting in several publications that documented the findings.

Image 1: Harbormaster propulsion unit (port, forward) shown in raised position. The four units are lowered to a vertical position when in use for positioning-keeping. Image 2: The drilling ship M/V Caldrill I is a converted 176-foot AKL-type navy vessel owned by Caldrill Offshore Inc. of Ventura, California. (Credit for both images: Schlee and Gerrard, 1965, no known copyright).

This short yet productive mission proved to be a significant learning experience for the JOIDES team. It allowed the scientists to work together in a real-world setting and refine the logistics of complex marine drilling operations. Scientifically, the project provided insights into the geological characteristics of the continental shelf and the Blake Plateau. On the practical side, it demonstrated that, by means of offshore drilling, fresh water aquifers located just over 80 kilometers (~50 miles) from Florida’s coastline could be recovered and piped to land.

The success of this preliminary program inspired JOIDES to consider extending their operations into even deeper waters. They envisioned a program involving a self-propelled vessel, similar to those used for shallow-water oil drilling. This vessel would be enhanced by what was now recognized as the all-too-essential dynamic positioning system. The vessel’s speed would allow for minimal transit time between drill sites, a crucial feature for efficient scientific exploration in deeper and more challenging environments.

The Start of DSDP

The drilling phase of the Ocean Sediment Coring Program was named the Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP). Originally supported as an eighteen-month drilling program, the project was carried out by the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, San Diego, under a negotiated cost contract, effective June 1966, with NSF. The primary objectives of the drilling project were to determine the age and processes of development of the ocean basins through the drilling of deep holes in the ocean floor with technology developed by the petroleum industry. JOIDES expanded their structure to include the following themed work groups for drilling locations:

- Atlantic Advisory Panel

- Recommended sites to (1) sample the oldest sediments; (2) test the hypotheses that predict the involvement of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge in the development of the basin; and (3) recover sedimentary sections for paleontologic and stratigraphic studies in areas where undisturbed sedimentation is believed to have taken place.

- Pacific Advisory Panel

- Recommended sites to (1) recover continuous sedimentary sections along a longitudinal (North-South) profile for paleontologic and stratigraphic studies; (2) sample the basins, ridges, and guyots in the northwest Pacific; (3) sample the East Pacific Rise to test hypothesis as to the development of the Pacific basin; and (4) sample near fracture zones to investigate the origin of the magnetic anomaly patterns and possible relative movement along the zones.

Additional work groups were established to define the research objectives:

- Panel on Paleontology and Biostratigraphy

- Panel on Igneous and Metamorphic Petrology

- Panel on Sedimentary Petrology and Geochemistry

- Panel on Logging

At-sea operations began in August 1968 with the drilling vessel Glomar Challenger (while DSDP was supported by the National Science Foundation and run through the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, the University of California subcontracted to Global Marine Incorporated for the services of Glomar Challenger). The original eighteen-month drilling project was deemed so successful that funding was extended beyond this initial period. The funding was from the National Science Foundation for the National Ocean Sediment Coring (NOSC) program through 1974. Moving forward, additional U.S. institutions began joining JOIDES and DSDP.

As the drilling program was expanding, so was the membership in JOIDES. The University of Washington joined JOIDES as the sixth institution in 1966. President Richard Nixon’s diplomatic visit to the Institute of Oceanology of the U.S.S.R. in 1972 played a role in expanding the international interest and participation in JOIDES. In October 1975, the scientific ocean drilling community officially expanded from national to global with the International Phase of Ocean Drilling (IPOD). This expansion included the participation of international institutions and governments, along with partial financial support, from the Soviet Union (sixth member of JOIDES), Federal Republic of Germany (seventh member of JOIDES), Japan, United Kingdom, Soviet Union, and France. The drilling activities also expanded its focus to include sampling deeper than the sediment layer and penetrating the basement layer of basalt.

Funded through 1983, the Deep Sea Drilling Project not only contributed significantly to the scientific knowledge about deep ocean material, but there were important technological contributions including:

- development of deepwater reentry capabilities (1970)

- development of the hydraulic piston corer (1979 – explained in more detail by Moore and Backman, 2019).

Before moving too far forward with the scientific ocean drilling timeline, the next chapter will discuss more about the drilling vessels and pathways to drilling expeditions.

References

Becker, K., Austin, J.A., Exon, N., Humphris, S., Kastner, M., McKenzie, J.A., Miller, K.G., Suyehiro, K., and Taira, A. (2019, March). Fifty Years of Scientific Ocean Drilling. Oceanography, 32(1): 17-21. https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2019.110

JOIDES (Joint Oceanographic Institutions Deep Earth Sampling group). (1967, September). Deep-Sea Drilling Project. The American Association of Petroleum Geologists Bulletin, 51(9): 1787-1802.

Lomask, M. (1976). A Minor Miracle: An Informal History of the National Science Foundation. National Science Foundation; U.S. Government Printing Office. 285 pages.

Moore, T., and Backman, J. (2019, March). Reading All the Pages in the Book on Climate History. Oceanography, 32(1): 28-30. https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2019.115

National Science Foundation (1972, November). Achievements, Cost, and Administration of the Ocean Sediment Coring Program. Report to the Congress. 54 pages.

Schlee, J., and Gerrard, R. (1965, August). Cruise Report and Preliminary Core Log M/V Caldrill I – 17 April to 17 May 1965. J.O.I.D.E.S. Blake Panel Report for NSF Grant GP-4233. 64 pages. (unpublished)