Coupled Equilibria (15.3)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe examples of systems involving two (or more) coupled chemical equilibria

- Calculate reactant and product concentrations for coupled equilibrium systems

As discussed in preceding chapters on equilibrium, coupled equilibria involve two or more separate chemical reactions that share one or more reactants or products. This section of this chapter will address solubility equilibria coupled with acid-base and complex-formation reactions.

An environmentally relevant example illustrating the coupling of solubility and acid-base equilibria is the impact of ocean acidification on the health of the ocean’s coral reefs. These reefs are built upon skeletons of sparingly soluble calcium carbonate excreted by colonies of corals (small marine invertebrates). The relevant dissolution equilibrium is

CaCO3(s) ⇌ Ca2+ (aq) + CO32− (aq) Ksp = 8.7 × 10−9

Rising concentrations of atmospheric carbon dioxide contribute to an increased acidity of ocean waters due to the dissolution, hydrolysis, and acid ionization of carbon dioxide:

CO2(g) ⇌ CO2(aq)

CO2(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ H2CO3(aq)

H2CO3(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ HCO3− (aq) + H3O+ (aq) Ka1 = 4.3 × 10−7

HCO3− (aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ CO32− (aq) + H3O+ (aq) Ka2= 4.7 × 10−11

Inspection of these equilibria shows the carbonate ion is involved in the calcium carbonate dissolution and the acid hydrolysis of bicarbonate ion. Combining the dissolution equation with the reverse of the acid hydrolysis equation yields

CaCO3(s) + H3O+ (aq) ⇌ Ca2+ (aq) + HCO3− (aq) + H2O (l) K = Ksp / Ka2 = 180

The equilibrium constant for this net reaction is much greater than the Ksp for calcium carbonate, indicating its solubility is markedly increased in acidic solutions. As rising carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere increase the acidity of ocean waters, the calcium carbonate skeletons of coral reefs become more prone to dissolution and subsequently less healthy (Figure 15.7).

Figure 15.7 Healthy coral reefs (a) support a dense and diverse array of sea life across the ocean food chain. But when coral are unable to adequately build and maintain their calcium carbonate skeletons because of excess ocean acidification, the unhealthy reef (b) is only capable of hosting a small fraction of the species as before, and the local food chain starts to collapse. (credit a: modification of work by NOAA Photo Library; credit b: modification of work by “prilfish”/Flickr)

Link to Learning

Learn more about ocean acidification and how it affects other marine creatures.

This site has detailed information about how ocean acidification specifically affects coral reefs.

The dramatic increase in solubility with increasing acidity described above for calcium carbonate is typical of salts containing basic anions (e.g., carbonate, fluoride, hydroxide, sulfide). Another familiar example is the formation of dental cavities in tooth enamel. The major mineral component of enamel is calcium hydroxyapatite (Figure 15.8), a sparingly soluble ionic compound whose dissolution equilibrium is

Ca5(PO4)3OH(s) ⇌ 5Ca2+(aq) + 3PO43−(aq) + OH−(aq)

Figure 15.8 Crystal of the mineral hydroxyapatite, Ca5(PO4)3OH, is shown here. The pure compound is white, but like many other minerals, this sample is colored because of the presence of impurities.

This compound dissolved to yield two different basic ions: triprotic phosphate ions

PO43−(aq) + H3O+(aq) ⟶ H2PO42−(aq) + H2O(l)

H2PO42−(aq) + H3O+(aq) ⟶ H2PO4−(aq) + H2O(l)

H2PO4−(aq) + H3O+(aq) ⟶ H3PO4(aq) + H2O(l)

and monoprotic hydroxide ions:

OH−(aq) + H3O+ ⟶ 2H2O

Of the two basic productions, the hydroxide is, of course, by far the stronger base (it’s the strongest base that can exist in aqueous solution), and so it is the dominant factor providing the compound an acid-dependent solubility. Dental cavities form when the acid waste of bacteria growing on the surface of teeth hastens the dissolution of tooth enamel by reacting completely with the strong base hydroxide, shifting the hydroxyapatite solubility equilibrium to the right. Some toothpastes and mouth rinses contain added NaF or SnF2 that make enamel more acid resistant by replacing the strong base hydroxide with the weak base fluoride:

NaF + Ca5(PO4)3OH ⇌ Ca5(PO4)3F + Na+ + OH−

The weak base fluoride ion reacts only partially with the bacterial acid waste, resulting in a less extensive shift in the solubility equilibrium and an increased resistance to acid dissolution. See the Chemistry in Everyday Life feature on the role of fluoride in preventing tooth decay for more information.

Chemistry in Everyday Life

Role of Fluoride in Preventing Tooth Decay

As we saw previously, fluoride ions help protect our teeth by reacting with hydroxylapatite to form fluorapatite, Ca5(PO4)3F. Since it lacks a hydroxide ion, fluorapatite is more resistant to attacks by acids in our mouths and is thus less soluble, protecting our teeth. Scientists discovered that naturally fluorinated water could be beneficial to your teeth, and so it became common practice to add fluoride to drinking water. Toothpastes and mouthwashes also contain amounts of fluoride (Figure 15.9).

Figure 15.9 Fluoride, found in many toothpastes, helps prevent tooth decay (credit: Kerry Ceszyk).

Unfortunately, excess fluoride can negate its advantages. Natural sources of drinking water in various parts of the world have varying concentrations of fluoride, and places where that concentration is high are prone to certain health risks when there is no other source of drinking water. The most serious side effect of excess fluoride is the bone disease, skeletal fluorosis. When excess fluoride is in the body, it can cause the joints to stiffen and the bones to thicken. It can severely impact mobility and can negatively affect the thyroid gland. Skeletal fluorosis is a condition that over 2.7 million people suffer from across the world. So while fluoride can protect our teeth from decay, the US Environmental Protection Agency sets a maximum level of 4 ppm (4 mg/L) of fluoride in drinking water in the US. Fluoride levels in water are not regulated in all countries, so fluorosis is a problem in areas with high levels of fluoride in the groundwater.

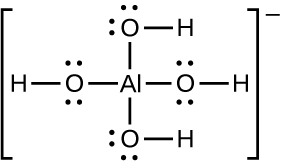

The solubility of ionic compounds may also be increased when dissolution is coupled to the formation of a complex ion. For example, aluminum hydroxide dissolves in a solution of sodium hydroxide or another strong base because of the formation of the complex ion Al(OH)4−.

The equations for the dissolution of aluminum hydroxide, the formation of the complex ion, and the combined (net) equation are shown below. As indicated by the relatively large value of K for the net reaction, coupling complex formation with dissolution drastically increases the solubility of Al(OH)3.

Al(OH)3(s) ⇌ Al3+(aq) + 3OH−(aq) Ksp = 2 × 10−32

Al3+(aq) + 4OH−(aq) ⇌ Al(OH)4−(aq) Kf = 1.1 × 1033

Net: Al(OH)3(s) + OH−(aq) ⇌ Al(OH)4−(aq) K = Ksp Kf = 22

Example 15.15

Increased Solubility in Acidic Solutions

Compute and compare the molar solublities for aluminum hydroxide, Ca(OH)2, dissolved in (a) pure water and (b) a buffer containing 0.100 M acetic acid and 0.100 M sodium acetate.

Solution

(a) The molar solubility of calcium fluoride in water is computed considering the dissolution equilibrium only as demonstrated in several previous examples:

Al(OH)3(s) ⇌ Al3+ (aq) + 3OH− (aq) Ksp = 2 × 10−32

molar solubility in water = [Al3+] = (2 × 10−32 / 27)1/3 = 9 × 10−12 M

(b) The concentration of hydroxide ion of the buffered solution is conveniently calculated by the Henderson- Hasselbalch equation:

pH = pKa + log [CH3 COO−] / [CH3 COOH]

pH = 4.74 + log (0.100 / 0.100) = 4.74

At this pH, the concentration of hydroxide ion is

pOH = 14.00 – 4.74 = 9.26

[OH−] = 10−9.26 = 5.5 × 10−10

The solubility of Al(OH)3 in this buffer is then calculated from its solubility product expressions:

Ksp = [Al3+][OH−]3

molar solubility in buffer = [Al3+] = Ksp / [OH−]3 = (2 × 10−32) / (5.5 × 10−10)3 = 1.2 × 10−4 M

Compared to pure water, the solubility of aluminum hydroxide in this mildly acidic buffer is approximately ten million times greater (though still relatively low).

Check Your Learning

What is the solubility of aluminum hydroxide in a buffer comprised of 0.100 M formic acid and 0.100M sodium formate?

Answer: 0.1 M

Example 15.16

Multiple Equilibria

Unexposed silver halides are removed from photographic film when they react with sodium thiosulfate (Na2S2O3, called hypo) to form the complex ion Ag(S2O3)23− (Kf = 4.7 × 1013).

What mass of Na2S2O3 is required to prepare 1.00 L of a solution that will dissolve 1.00 g of AgBr by the formation of Ag(S2O3)23− ?

Solution

Two equilibria are involved when AgBr dissolves in a solution containing the S2O32− ion:

dissolution: AgBr(s) ⇌ Ag+(aq) + Br−(aq) Ksp = 5.0 × 10−13

complexation: Ag+(aq) + 2S2O32−(aq) ⇌ Ag(S2O3)23−(aq) Kf = 4.7 × 1013

First, calculate the concentration of bromide that will result when the 1.00 g of AgBr is completely dissolved via the cited complexation reaction:

1.00 g AgBr / (187.77 g/mol)(1 mol Br− / 1 mol AgBr) = 0.00532 mol Br–

0.00521 mol Br− / 1.00 L = 0.00521 M Br−

Next, use this bromide molarity and the solubility product for silver bromide to calculate the silver ion molarity in the solution:

[Ag+] = Ksp / [Br−] = 5.0 × 10−13 / 0.00521 = 9.6 × 10−11 M

Based on the stoichiometry of the complex ion formation, the concentration of complex ion produced is

0.00521 – 9.6 × 10−11 = 0.00521 M

Use the silver ion and complex ion concentrations and the formation constant for the complex ion to compute the concentration of thiosulfate ion.

[S2O32-]2 = [Ag(S2O3)23-]/[Ag+]Kf = 0.00521/(9.6 x 10-11)(4.7 x 1013) = 1.15 x 10-6

[S2O32-] = 1.1 x 10-3 M

Finally, use this molar concentration to derive the required mass of sodium thiosulfate:

(1.1 × 10−3 mol S2O32− / L)(1 mol Na2S2O3 / 1 mol S2O32− )(158.1 g Na2S2O3 / mol) = 1.7 g

Thus, 1.00 L of a solution prepared from 1.7 g Na2S2O3 dissolves 1.0 g of AgBr.

Check Your Learning

AgCl(s), silver chloride, has a very low solubility: AgCl(s) ⇌ Ag+(aq) + Cl−(aq), Ksp = 1.6 × 10–10. Adding ammonia significantly increases the solubility of AgCl because a complex ion is formed: Ag+(aq) + 2NH3(aq) ⇌ Ag(NH3)2+ (aq), Kf = 1.7 × 107. What mass of NH3 is required to prepare 1.00L of solution that will dissolve 2.00 g of AgCl by formation of Ag(NH3)2+ ?

Answer: 1.00 L of a solution prepared with 4.81 g NH3 dissolves 2.0 g of AgCl.

Key Terms

common ion effect effect on equilibrium when a substance with an ion in common with the dissolved species is added to the solution; causes a decrease in the solubility of an ionic species, or a decrease in the ionization of a weak acid or base

complex ion ion consisting of a central atom surrounding molecules or ions called ligands via coordinate covalent bonds

coordinate covalent bond (also, dative bond) covalent bond in which both electrons originated from the same atom

coupled equilibria system characterized the simultaneous establishment of two or more equilibrium reactions sharing one or more reactant or product

dissociation constant (Kd) equilibrium constant for the decomposition of a complex ion into its components

formation constant (Kf) (also, stability constant) equilibrium constant for the formation of a complex ion from its components

Lewis acid any species that can accept a pair of electrons and form a coordinate covalent bond

Lewis acid-base adduct compound or ion that contains a coordinate covalent bond between a Lewis acid and a Lewis base

Lewis acid-base chemistry reactions involving the formation of coordinate covalent bonds

Lewis base any species that can donate a pair of electrons and form a coordinate covalent bond

ligand molecule or ion acting as a Lewis base in complex ion formation; bonds to the central atom of the complex

molar solubility solubility of a compound expressed in units of moles per liter (mol/L)

selective precipitation process in which ions are separated using differences in their solubility with a given precipitating reagent

solubility product constant (Ksp) equilibrium constant for the dissolution of an ionic compound

Key Equations

- MpXq(s) ⇌ pMm+(aq) + qXn−(aq) Ksp = [Mm+ ]p[Xn−]q

Summary

Precipitation and Dissolution

The equilibrium constant for an equilibrium involving the precipitation or dissolution of a slightly soluble ionic solid is called the solubility product, Ksp, of the solid. For a heterogeneous equilibrium involving the slightly soluble solid MpXq and its ions Mm+ and Xn–:

MpXq(s) ⇌ pMm+(aq) + qXn−(aq)

the solubility product expression is:

Ksp = [Mm+]p [Xn−]q

The solubility product of a slightly soluble electrolyte can be calculated from its solubility; conversely, its solubility can be calculated from its Ksp, provided the only significant reaction that occurs when the solid dissolves is the formation of its ions.

A slightly soluble electrolyte begins to precipitate when the magnitude of the reaction quotient for the dissolution reaction exceeds the magnitude of the solubility product. Precipitation continues until the reaction quotient equals the solubility product.

Lewis Acids and Bases

A Lewis acid is a species that can accept an electron pair, whereas a Lewis base has an electron pair available for donation to a Lewis acid. Complex ions are examples of Lewis acid-base adducts and comprise central metal atoms or ions acting as Lewis acids bonded to molecules or ions called ligands that act as Lewis bases. The equilibrium constant for the reaction between a metal ion and ligands produces a complex ion called a formation constant; for the reverse reaction, it is called a dissociation constant.

Coupled Equilibria

Systems involving two or more chemical equilibria that share one or more reactant or product are called coupled equilibria. Common examples of coupled equilibria include the increased solubility of some compounds in acidic solutions (coupled dissolution and neutralization equilibria) and in solutions containing ligands (coupled dissolution and complex formation). The equilibrium tools from other chapters may be applied to describe and perform calculations on these systems.

Exercises

15.1 Precipitation and Dissolution

1.) Complete the changes in concentrations for each of the following reactions:

(a) AgI(s) ⟶ Ag+(aq) + I−(aq)

x ___

(b) CaCO3(s) ⟶ Ca2+(aq) + CO3 2−(aq)

___ x

(c) Mg(OH)2(s) ⟶ Mg2+(aq) + 2OH−(aq)

x ___

(d) Mg3(PO4 )2(s) ⟶ 3Mg2+(aq) + 2PO4 3−(aq)

x___

(e) Ca5(PO4 )3OH(s) ⟶ 5Ca2+(aq) + 3PO4 3−(aq) + OH−(aq)

___ ___ x

2.) Complete the changes in concentrations for each of the following reactions:

(a) BaSO4(s) ⟶ Ba2+(aq) + SO42−(aq)

x ___

(b) Ag2 SO4(s) ⟶ 2Ag+(aq) + SO42−(aq)

___ x

(c) Al(OH)3(s) ⟶ Al3+(aq) + 3OH−(aq)

x ___

(d) Pb(OH)Cl(s) ⟶ Pb2+(aq) + OH−(aq) + Cl−(aq)

___ x ___

(e) Ca3(AsO4 )2(s) ⟶ 3Ca2+(aq) + 2AsO43−(aq)

3x ___

- How do the concentrations of Ag+ and CrO42− in a saturated solution above 1.0 g of solid Ag2CrO4 change when 100 g of solid Ag2CrO4 is added to the system? Explain.

- How do the concentrations of Pb2+ and S2– change when K2S is added to a saturated solution of PbS?

- What additional information do we need to answer the following question: How is the equilibrium of solid silver bromide with a saturated solution of its ions affected when the temperature is raised?

- Which of the following slightly soluble compounds has a solubility greater than that calculated from its solubility product because of hydrolysis of the anion present: CoSO3, CuI, PbCO3, PbCl2, Tl2S, KClO4?

- Which of the following slightly soluble compounds has a solubility greater than that calculated from its solubility product because of hydrolysis of the anion present: AgCl, BaSO4, CaF2, Hg2I2, MnCO3, ZnS, PbS?

- Write the ionic equation for dissolution and the solubility product (Ksp) expression for each of the following slightly soluble ionic compounds:

- PbCl2

- Ag2S

- Sr3(PO4)2

- SrSO4

- Write the ionic equation for the dissolution and the Ksp expression for each of the following slightly soluble ionic compounds:

- LaF3

- CaCO3

- Ag2SO4

- Pb(OH)2

- The Handbook of Chemistry and Physics gives solubilities of the following compounds in grams per 100 mL of water. Because these compounds are only slightly soluble, assume that the volume does not change on dissolution and calculate the solubility product for each.(a) BaSiF6, 0.026 g/100 mL (contains SiF6 2− ions)(b) Ce(IO3)4, 1.5 × 10–2 g/100 mL(c) Gd2(SO4)3, 3.98 g/100 mL(d) (NH4)2PtBr6, 0.59 g/100 mL (contains PtBr6 2− ions)

- The Handbook of Chemistry and Physics gives solubilities of the following compounds in grams per 100 mL of water. Because these compounds are only slightly soluble, assume that the volume does not change on dissolution and calculate the solubility product for each.

- BaSeO4, 0.0118 g/100 mL

- Ba(BrO3)2∙H2O, 0.30 g/100 mL

- NH4MgAsO4∙6H2O, 0.038 g/100 mL

- La2(MoO4)3, 0.00179 g/100 mL

-

- Use solubility products and predict which of the following salts is the most soluble, in terms of moles per liter, in pure water: CaF2, Hg2Cl2, PbI2, or Sn(OH)2.

- Assuming that no equilibria other than dissolution are involved, calculate the molar solubility of each of the following from its solubility product:

- KHC4H4O6

- PbI2

- Ag4[Fe(CN)6], a salt containing the Fe(CN)4− ion

- Hg2I2

- Assuming that no equilibria other than dissolution are involved, calculate the molar solubility of each of the following from its solubility product:

- Ag2SO4

- PbBr2

- AgI

- CaC2O4∙H2O

- Assuming that no equilibria other than dissolution are involved, calculate the concentration of all solute species in each of the following solutions of salts in contact with a solution containing a common ion. Show that changes in the initial concentrations of the common ions can be neglected.

- AgCl(s) in 0.025 M NaCl

- CaF2(s) in 0.00133 M KF

- Ag2SO4(s) in 0.500 L of a solution containing 19.50 g of K2SO4

- Zn(OH)2(s) in a solution buffered at a pH of 11.45

- Assuming that no equilibria other than dissolution are involved, calculate the concentration of all solute species in each of the following solutions of salts in contact with a solution containing a common ion. Show that changes in the initial concentrations of the common ions can be neglected.

- TlCl(s) in 1.250 M HCl

- PbI2(s) in 0.0355 M CaI2

- Ag2CrO4(s) in 0.225 L of a solution containing 0.856 g of K2CrO4

- Cd(OH)2(s) in a solution buffered at a pH of 10.995

- Assuming that no equilibria other than dissolution are involved, calculate the concentration of all solute species in each of the following solutions of salts in contact with a solution containing a common ion. Show that it is not appropriate to neglect the changes in the initial concentrations of the common ions.

- TlCl(s) in 0.025 M TlNO3

- BaF2(s) in 0.0313 M KF

- MgC2O4 in 2.250 L of a solution containing 8.156 g of Mg(NO3)2

- Ca(OH)2(s) in an unbuffered solution initially with a pH of 12.700

- Explain why the changes in concentrations of the common ions in Exercise 15.17 can be neglected.

- Explain why the changes in concentrations of the common ions in Exercise 15.18 cannot be neglected.

- Calculate the solubility of aluminum hydroxide, Al(OH)3, in a solution buffered at pH 11.00.

- Refer to Appendix J for solubility products for calcium salts. Determine which of the calcium salts listed is most soluble in moles per liter and which is most soluble in grams per liter.

- Most barium compounds are very poisonous; however, barium sulfate is often administered internally as an aid in the X-ray examination of the lower intestinal tract (Figure 15.4). This use of BaSO4 is possible because of its low solubility. Calculate the molar solubility of BaSO4 and the mass of barium present in 1.00 L of water saturated with BaSO4.

- Public Health Service standards for drinking water set a maximum of 250 mg/L (2.60 × 10–3 M) of SO4 2− because of its cathartic action (it is a laxative). Does natural water that is saturated with CaSO4 (“gyp” water) as a result or passing through soil containing gypsum, CaSO4∙2H2O, meet these standards? What is the concentration of SO4 2− in such water?

- Perform the following calculations:

- Calculate [Ag+] in a saturated aqueous solution of AgBr.

- What will [Ag+] be when enough KBr has been added to make [Br–] = 0.050 M?

- What will [Br–] be when enough AgNO3 has been added to make [Ag+] = 0.020 M?

- The solubility product of CaSO4∙2H2O is 2.4 × 10–5. What mass of this salt will dissolve in 1.0 L of 0.010 M SO42− ?

- Assuming that no equilibria other than dissolution are involved, calculate the concentrations of ions in a saturated solution of each of the following (see Appendix J for solubility products).

- TlCl

- BaF2

- Ag2CrO4

- CaC2O4∙H2O

- the mineral anglesite, PbSO4

- Assuming that no equilibria other than dissolution are involved, calculate the concentrations of ions in a saturated solution of each of the following (see Appendix J for solubility products):

- AgI

- Ag2SO4

- Mn(OH)2

- Sr(OH)2∙8H2O

- the mineral brucite, Mg(OH)2

- The following concentrations are found in mixtures of ions in equilibrium with slightly soluble solids. From the concentrations given, calculate Ksp for each of the slightly soluble solids indicated:

- AgBr: [Ag+] = 5.7 × 10–7 M, [Br–] = 5.7 × 10–7 M

- CaCO3: [Ca2+] = 5.3 × 10–3 M, [CO32−] = 9.0 × 10–7 M

- PbF2: [Pb2+] = 2.1 × 10–3 M, [F–] = 4.2 × 10–3 M

- Ag2CrO4: [Ag+] = 5.3 × 10–5 M, 3.2 × 10–3 M

- InF3: [In3+] = 2.3 × 10–3 M, [F–] = 7.0 × 10–3 M

- The following concentrations are found in mixtures of ions in equilibrium with slightly soluble solids. From the concentrations given, calculate Ksp for each of the slightly soluble solids indicated:

- TlCl: [Tl+] = 1.21 × 10–2 M, [Cl–] = 1.2 × 10–2 M

- Ce(IO3)4: [Ce4+] = 1.8 × 10–4 M, [IO3−] = 2.6 × 10–13 M

- Gd2(SO4)3: [Gd3+] = 0.132 M, [SO42−] = 0.198 M

- Ag2SO4: [Ag+] = 2.40 × 10–2 M, [SO42−] = 2.05 × 10–2 M

- BaSO4: [Ba2+] = 0.500 M, [SO42−] = 4.6 × 10−8 M

- Which of the following compounds precipitates from a solution that has the concentrations indicated? (See Appendix J for Ksp values.)

- KClO4: [K+] = 0.01 M, [ClO4−] = 0.01 M

- K2PtCl6: [K+] = 0.01 M, [PtCl62−] = 0.01 M

- PbI2: [Pb2+] = 0.003 M, [I–] = 1.3 × 10–3 M

- Ag2S: [Ag+] = 1 × 10–10 M, [S2–] = 1 × 10–13 M

- Which of the following compounds precipitates from a solution that has the concentrations indicated? (See Appendix J for Ksp values.)

- CaCO3: [Ca2+] = 0.003 M, [CO32−] = 0.003 M

- Co(OH)2: [Co2+] = 0.01 M, [OH–] = 1 × 10–7 M

- CaHPO4: [Ca2+] = 0.01 M, [HPO42−] = 2 × 10–6 M

- Pb3(PO4)2: [Pb2+] = 0.01 M, [PO43−] = 1 × 10–13 M

- Calculate the concentration of Tl+ when TlCl just begins to precipitate from a solution that is 0.0250 M in Cl–.

- Calculate the concentration of sulfate ion when BaSO4 just begins to precipitate from a solution that is 0.0758 M in Ba2+.

- Calculate the concentration of Sr2+ when SrF2 starts to precipitate from a solution that is 0.0025 M in F–.

- Calculate the concentration of PO4 3− when Ag3PO4 starts to precipitate from a solution that is 0.0125 M in Ag+.

- Calculate the concentration of F– required to begin precipitation of CaF2 in a solution that is 0.010 M in Ca2+.

- Calculate the concentration of Ag+ required to begin precipitation of Ag2CO3 in a solution that is 2.50 × 10–6 M in CO32−.

- What [Ag+] is required to reduce [CO3 2−] to 8.2 × 10–4 M by precipitation of Ag2CO3?

- What [F–] is required to reduce [Ca2+] to 1.0 × 10–4 M by precipitation of CaF2?

- A volume of 0.800 L of a 2 × 10–4-M Ba(NO3)2 solution is added to 0.200 L of 5 × 10–4 M Li2SO4. Does BaSO4 precipitate? Explain your answer.

- Perform these calculations for nickel(II) carbonate.

- With what volume of water must a precipitate containing NiCO3 be washed to dissolve 0.100 g of this compound? Assume that the wash water becomes saturated with NiCO3 (Ksp = 1.36 × 10–7).

- If the NiCO3 were a contaminant in a sample of CoCO3 (Ksp = 1.0 × 10–12), what mass of CoCO3 would have been lost? Keep in mind that both NiCO3 and CoCO3 dissolve in the same solution.

- Iron concentrations greater than 5.4 × 10–6 M in water used for laundry purposes can cause staining. What [OH–] is required to reduce [Fe2+] to this level by precipitation of Fe(OH)2?

- A solution is 0.010 M in both Cu2+ and Cd2+. What percentage of Cd2+ remains in the solution when 99.9% of the Cu2+ has been precipitated as CuS by adding sulfide?

- A solution is 0.15 M in both Pb2+ and Ag+. If Cl– is added to this solution, what is [Ag+] when PbCl2 begins to precipitate?

- What reagent might be used to separate the ions in each of the following mixtures, which are 0.1 M with respect to each ion? In some cases it may be necessary to control the pH. (Hint: Consider the Ksp values given in Appendix J.)

- Hg2 2+ and Cu2+

- SO4 2− and Cl–

- Hg2+ and Co2+

- Zn2+ and Sr2+

- Ba2+ and Mg2+

- CO3 2− and OH–

- A solution contains 1.0 × 10–5 mol of KBr and 0.10 mol of KCl per liter. AgNO3 is gradually added to this solution. Which forms first, solid AgBr or solid AgCl?

- A solution contains 1.0 × 10–2 mol of KI and 0.10 mol of KCl per liter. AgNO3 is gradually added to this solution. Which forms first, solid AgI or solid AgCl?

- The calcium ions in human blood serum are necessary for coagulation (Figure 15.5). Potassium oxalate, K2C2O4, is used as an anticoagulant when a blood sample is drawn for laboratory tests because it removes the calcium as a precipitate of CaC2O4∙H2O. It is necessary to remove all but 1.0% of the Ca2+ in serum in order to prevent coagulation. If normal blood serum with a buffered pH of 7.40 contains 9.5 mg of Ca2+ per 100 mL of serum, what mass of K2C2O4 is required to prevent the coagulation of a 10 mL blood sample that is 55% serum by volume? (All volumes are accurate to two significant figures. Note that the volume of serum in a 10-mL blood sample is 5.5 mL. Assume that the Ksp value for CaC2O4 in serum is the same as in water.)

- About 50% of urinary calculi (kidney stones) consist of calcium phosphate, Ca3(PO4)2. The normal mid range calcium content excreted in the urine is 0.10 g of Ca2+ per day. The normal mid range amount of urine passed may be taken as 1.4 L per day. What is the maximum concentration of phosphate ion that urine can contain before a calculus begins to form?

- The pH of normal urine is 6.30, and the total phosphate concentration ([PO43−] + [HPO42−] + [H2PO4−] What is the minimum concentration of Ca2+ necessary to induce kidney stone formation? (See Exercise 15.49 for additional information.)

- Magnesium metal (a component of alloys used in aircraft and a reducing agent used in the production of uranium, titanium, and other active metals) is isolated from sea water by the following sequence of reactions: Mg2+(aq) + Ca(OH)2(aq) ⟶ Mg(OH)2(s) + Ca2+(aq)

Mg(OH)2(s) + 2HCl(aq) ⟶ MgCl2(s) + 2H2O(l)

MgCl2(l) [latex]\overset{electrolysis}{\longrightarrow}[/latex] Mg(s) + Cl2(g)

Sea water has a density of 1.026 g/cm3 and contains 1272 parts per million of magnesium as Mg2+(aq) by mass. What mass, in kilograms, of Ca(OH)2 is required to precipitate 99.9% of the magnesium in 1.00 × 103 L of sea water? - Hydrogen sulfide is bubbled into a solution that is 0.10 M in both Pb2+ and Fe2+ and 0.30 M in HCl. After the solution has come to equilibrium it is saturated with H2S ([H2S] = 0.10 M). What concentrations of Pb2+ and Fe2+ remain in the solution? For a saturated solution of H2S we can use the equilibrium:H2S(aq) + 2H2O(l) ⇌ 2H3O+(aq) + S2−(aq)K = 1.0 × 10−26(Hint: The [H3O+] changes as metal sulfides precipitate.)

- Perform the following calculations involving concentrations of iodate ions:

- The iodate ion concentration of a saturated solution of La(IO3)3 was found to be 3.1 × 10–3 mol/L. Find the Ksp.

- Find the concentration of iodate ions in a saturated solution of Cu(IO3)2 (Ksp = 7.4 × 10–8).

- Calculate the molar solubility of AgBr in 0.035 M NaBr (Ksp = 5 × 10–13).

- How many grams of Pb(OH)2 will dissolve in 500 mL of a 0.050-M PbCl2 solution (Ksp = 1.2 × 10–15)?

- Use the simulation from the earlier Link to Learning to complete the following exercise. Using 0.01 g CaF2, give the Ksp values found in a 0.2-M solution of each of the salts. Discuss why the values change as you change soluble salts.

- How many grams of Milk of Magnesia, Mg(OH)2 (s) (58.3 g/mol), would be soluble in 200 mL of water. Ksp = 7.1 × 10–12. Include the ionic reaction and the expression for Ksp in your answer. (Kw = 1 × 10–14 = [H3O+][OH–])

- Two hypothetical salts, LM2 and LQ, have the same molar solubility in H2O. If Ksp for LM2 is 3.20 × 10–5, what is the Ksp value for LQ?

- The carbonate ion concentration is gradually increased in a solution containing divalent cations of magnesium, calcium, strontium, barium, and manganese. Which of the following carbonates will form first? Which of the following will form last? Explain.

- MgCO3 Ksp = 3.5 × 10−8

- CaCO3 Ksp = 4.2 × 10−7

- SrCO3 Ksp = 3.9 × 10−9

- BaCO3 Ksp = 4.4 × 10−5

- MnCO3 Ksp = 5.1 × 10−9

- How many grams of Zn(CN)2(s) (117.44 g/mol) would be soluble in 100 mL of H2O? Include the balanced reaction and the expression for Ksp in your answer. The Ksp value for Zn(CN)2(s) is 3.0 × 10–16.

- Even though Ca(OH)2 is an inexpensive base, its limited solubility restricts its use. What is the pH of a saturated solution of Ca(OH)2?

- Under what circumstances, if any, does a sample of solid AgCl completely dissolve in pure water?

- Explain why the addition of NH3 or HNO3 to a saturated solution of Ag2CO3 in contact with solid Ag2CO3 increases the solubility of the solid.

- Calculate the cadmium ion concentration, [Cd2+], in a solution prepared by mixing 0.100 L of 0.0100 with 1.150 L of 0.100 NH3(aq).

- Explain why addition of NH3 or HNO3 to a saturated solution of Cu(OH)2 in contact with solid Cu(OH)2 increases the solubility of the solid.

- Sometimes equilibria for complex ions are described in terms of dissociation constants, Kd. For the complex ion AlF6 3− the dissociation reaction is:

AlF63− ⇌ Al3+ + 6F− and Kd = [latex]\frac{[al^{3+}][F^{-}]^{6}}{[AlF_{6}^{3-}]}[/latex]

Calculate the value of the formation constant, Kf, for AlF6 3−.

- Using the value of the formation constant for the complex ion Co(NH3)6 2+, calculate the dissociation constant.

- Using the dissociation constant, Kd = 7.8 × 10–18, calculate the equilibrium concentrations of Cd2+ and CN– in a 0.250-M solution of Cd(CN)42−.

- Using the dissociation constant, Kd = 3.4 × 10–15, calculate the equilibrium concentrations of Zn2+ and OH– in a 0.0465-M solution of Zn(OH)42−.

- Using the dissociation constant, Kd = 2.2 × 10–34, calculate the equilibrium concentrations of Co3+ and NH3 in a 0.500-M solution of Co(NH3)63+.

- Using the dissociation constant, Kd = 1 × 10–44, calculate the equilibrium concentrations of Fe3+ and CN– in a 0.333 M solution of Fe(CN)63−.

- Calculate the mass of potassium cyanide ion that must be added to 100 mL of solution to dissolve 2.0 × 10–2 mol of silver cyanide, AgCN.

- Calculate the minimum concentration of ammonia needed in 1.0 L of solution to dissolve 3.0 × 10–3 mol of silver bromide.

- A roll of 35-mm black and white photographic film contains about 0.27 g of unexposed AgBr before developing. What mass of Na2S2O3∙5H2O (sodium thiosulfate pentahydrate or hypo) in 1.0 L of developer is required to dissolve the AgBr as Ag(S2O3)23− (Kf = 4.7 × 1013)?

- We have seen an introductory definition of an acid: An acid is a compound that reacts with water and increases the amount of hydronium ion present. In the chapter on acids and bases, we saw two more definitions of acids: a compound that donates a proton (a hydrogen ion, H+) to another compound is called a Brønsted-Lowry acid, and a Lewis acid is any species that can accept a pair of electrons. Explain why the introductory definition is a macroscopic definition, while the Brønsted-Lowry definition and the Lewis definition are microscopic definitions.

- Write the Lewis structures of the reactants and product of each of the following equations, and identify the Lewis acid and the Lewis base in each:

- CO2 + OH− ⟶ HCO3−

- B(OH)3 + OH− ⟶ B(OH)4−

- I− + I2 ⟶ I3−

- AlCl3 + Cl− ⟶ AlCl4− (use Al-Cl single bonds)

- O2− + SO3 ⟶ SO42−

- Write the Lewis structures of the reactants and product of each of the following equations, and identify the Lewis acid and the Lewis base in each:

- CS2 + SH− ⟶ HCS3−

- BF3 + F− ⟶ BF4−

- I− + SnI2 ⟶ SnI3−

- Al(OH)3 + OH− ⟶ Al(OH)4−

- F− + SO3 ⟶ SFO3−

- Using Lewis structures, write balanced equations for the following reactions:

- HCl(g) + PH3(g) ⟶

- H3O+ + CH3− ⟶

- CaO + SO3 ⟶

- NH4 + + C2H5O− ⟶

- Calculate [HgCl42−] in a solution prepared by adding 0.0200 mol of NaCl to 0.250 L of a 0.100-M HgCl2 solution.

- In a titration of cyanide ion, 28.72 mL of 0.0100 M AgNO3 is added before precipitation begins. [The reaction of Ag+ with CN– goes to completion, producing the Ag(CN)2− complex.] Precipitation of solid AgCN takes place when excess Ag+ is added to the solution, above the amount needed to complete the formation of Ag(CN)2−. How many grams of NaCN were in the original sample?

- What are the concentrations of Ag+, CN–, and Ag(CN)2− in a saturated solution of AgCN?

- In dilute aqueous solution HF acts as a weak acid. However, pure liquid HF (boiling point = 19.5 °C) is a strong acid. In liquid HF, HNO3 acts like a base and accepts protons. The acidity of liquid HF can be increased by adding one of several inorganic fluorides that are Lewis acids and accept F– ion (for example, BF3 or SbF5). Write balanced chemical equations for the reaction of pure HNO3 with pure HF and of pure HF with BF3.

- The simplest amino acid is glycine, H2NCH2CO2H. The common feature of amino acids is that they contain the functional groups: an amine group, –NH2, and a carboxylic acid group, –CO2H. An amino acid can function as either an acid or a base. For glycine, the acid strength of the carboxyl group is about the same as that of acetic acid, CH3CO2H, and the base strength of the amino group is slightly greater than that of ammonia, NH3.

- Write the Lewis structures of the ions that form when glycine is dissolved in 1 M HCl and in 1 M KOH.

- Write the Lewis structure of glycine when this amino acid is dissolved in water. (Hint: Consider the relative base strengths of the –NH2 and −CO2 − groups.)

- Boric acid, H3BO3, is not a Brønsted-Lowry acid but a Lewis acid.

- Write an equation for its reaction with water.

- Predict the shape of the anion thus formed.

- What is the hybridization on the boron consistent with the shape you have predicted?

- A saturated solution of a slightly soluble electrolyte in contact with some of the solid electrolyte is said to be a system in equilibrium. Explain. Why is such a system called a heterogeneous equilibrium?

- Calculate the equilibrium concentration of Ni2+ in a 1.0-M solution [Ni(NH3)6](NO3)2.

- Calculate the equilibrium concentration of Zn2+ in a 0.30-M solution of Zn(CN)42−.

- Calculate the equilibrium concentration of Cu2+ in a solution initially with 0.050 M Cu2+ and 1.00 M NH3.

- Calculate the equilibrium concentration of Zn2+ in a solution initially with 0.150 M Zn2+ and 2.50 M CN–.

- Calculate the Fe3+ equilibrium concentration when 0.0888 mole of K3[Fe(CN)6] is added to a solution with 0.0.00010 M CN–.

- Calculate the Co2+ equilibrium concentration when 0.100 mole of [Co(NH3)6](NO3)2 is added to a solution with 0.025 M NH3. Assume the volume is 1.00 L.

- Calculate the molar solubility of Sn(OH)2 in a buffer solution containing equal concentrations of NH3 and NH4+.

- Calculate the molar solubility of Al(OH)3 in a buffer solution with 0.100 M NH3 and 0.400 M NH4+.

- What is the molar solubility of CaF2 in a 0.100-M solution of HF? Ka for HF = 6.4 × 10–4.

- What is the molar solubility of BaSO4 in a 0.250-M solution of NaHSO4? Ka for HSO4− = 1.2 × 10–2.

- What is the molar solubility of Tl(OH)3 in a 0.10-M solution of NH3?

- What is the molar solubility of Pb(OH)2 in a 0.138-M solution of CH3NH2?

- A solution of 0.075 M CoBr2 is saturated with H2S ([H2S] = 0.10 M). What is the minimum pH at which CoS begins to precipitate?

- CoS(s) ⇌ Co2+(aq) + S2−(aq) Ksp = 4.5 × 10−27

- H2S(aq) + 2H2O(l) ⇌ 2H3O+(aq) + S2−(aq) K = 1.0 × 10−26

- A 0.125-M solution of Mn(NO3)2 is saturated with H2S ([H2S] = 0.10 M). At what pH does MnS begin to precipitate?

- MnS(s) ⇌ Mn2+(aq) + S2−(aq) Ksp = 4.3 × 10−22

- H2S(aq) + 2H2O(l) ⇌ 2H3O+(aq) + S2−(aq) K = 1.0 × 10−26

- Both AgCl and AgI dissolve in NH3.

- What mass of AgI dissolves in 1.0 L of 1.0 M NH3?

- What mass of AgCl dissolves in 1.0 L of 1.0 M NH3?

- The following question is taken from a Chemistry Advanced Placement Examination and is used with the permission of the Educational Testing Service.

Solve the following problem:MgF2(s) ⇌ Mg2+(aq) + 2F−(aq)In a saturated solution of MgF2 at 18 °C, the concentration of Mg2+ is 1.21 × 10–3 M. The equilibrium is represented by the preceding equation.- Write the expression for the solubility-product constant, Ksp, and calculate its value at 18 °C.

- Calculate the equilibrium concentration of Mg2+ in 1.000 L of saturated MgF2 solution at 18 °C to which 0.100 mol of solid KF has been added. The KF dissolves completely. Assume the volume change is negligible.

- Predict whether a precipitate of MgF2 will form when 100.0 mL of a 3.00 × 10–3-M solution of Mg(NO3)2 is mixed with 200.0 mL of a 2.00 × 10–3-M solution of NaF at 18 °C. Show the calculations to support your prediction.

- At 27 °C the concentration of Mg2+ in a saturated solution of MgF2 is 1.17 × 10–3 M. Is the dissolving of MgF2 in water an endothermic or an exothermic process? Give an explanation to support your conclusion.

- Which of the following compounds, when dissolved in a 0.01-M solution of HClO4, has a solubility greater than in pure water: CuCl, CaCO3, MnS, PbBr2, CaF2? Explain your answer.

- Which of the following compounds, when dissolved in a 0.01-M solution of HClO4, has a solubility greater than in pure water: AgBr, BaF2, Ca3(PO4)2, ZnS, PbI2? Explain your answer.

- What is the effect on the amount of solid Mg(OH)2 that dissolves and the concentrations of Mg2+ and OH– when each of the following are added to a mixture of solid Mg(OH)2 and water at equilibrium?

- MgCl2

- KOH

- HClO4

- NaNO3

- Mg(OH)2

- What is the effect on the amount of CaHPO4 that dissolves and the concentrations of Ca2+ and HPO4 − when each of the following are added to a mixture of solid CaHPO4 and water at equilibrium?

- CaCl2

- HCl

- KClO4

- NaOH

- CaHPO4

- Identify all chemical species present in an aqueous solution of Ca3(PO4)2 and list these species in decreasing order of their concentrations. (Hint: Remember that the PO4 3− ion is a weak base.)