Electrolysis (17.7)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section you will be able to:

- Describe the process of electrolysis

- Compare the operation of electrolytic cells with that of galvanic cells

- Perform stoichiometric calculations for electrolytic processes

Electrochemical cells in which spontaneous redox reactions take place (galvanic cells) have been the topic of discussion so far in this chapter. In these cells, electrical work is done by a redox system on its surroundings as electrons produced by the redox reaction are transferred through an external circuit. This final section of the chapter will address an alternative scenario in which an external circuit does work on a redox system by imposing a voltage sufficient to drive an otherwise nonspontaneous reaction, a process known as electrolysis. A familiar example of electrolysis is recharging a battery, which involves use of an external power source to drive the spontaneous (discharge) cell reaction in the reverse direction, restoring to some extent the composition of the half-cells and the voltage of the battery. Perhaps less familiar is the use of electrolysis in the refinement of metallic ores, the manufacture of commodity chemicals, and the electroplating of metallic coatings on various products (e.g., jewelry, utensils, auto parts). To illustrate the essential concepts of electrolysis, a few specific processes will be considered.

The Electrolysis of Molten Sodium Chloride

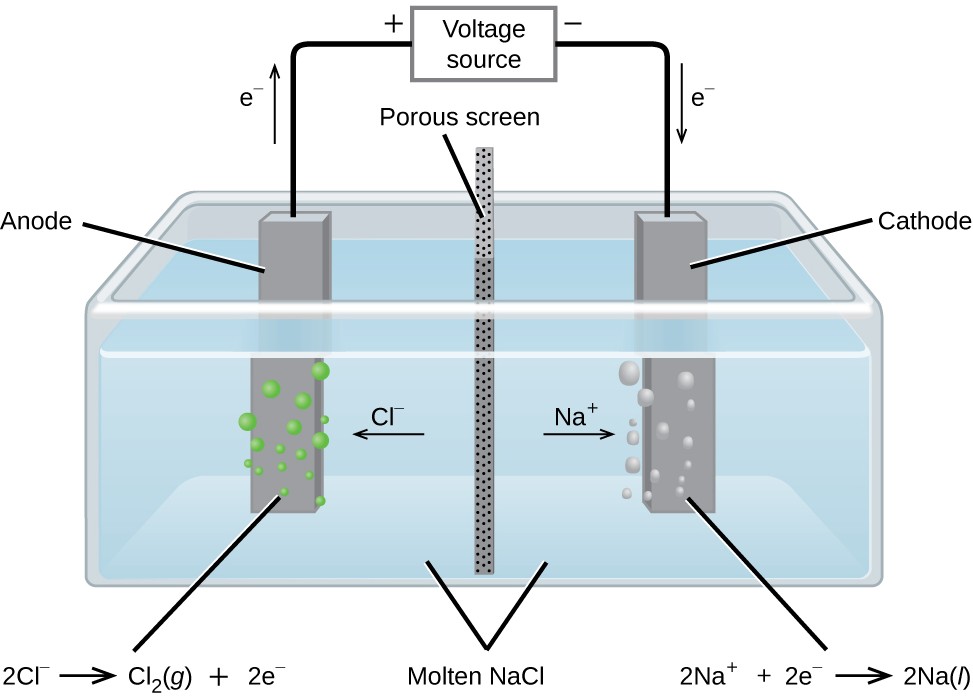

Metallic sodium, Na, and chlorine gas, Cl2, are used in numerous applications, and their industrial production relies on the large-scale electrolysis of molten sodium chloride, NaCl(l). The industrial process typically uses a Downs cell similar to the simplified illustration shown in Figure 17.18. The reactions associated with this process are:

anode:2Cl−(l) ⟶ Cl2(g) + 2e−

cathode:Na+(l) + e− ⟶ Na(l)

cell:2Na+(l) + 2Cl−(l) ⟶ 2Na(l) + Cl2(g)

The cell potential for the above process is negative, indicating the reaction as written (decomposition of liquid NaCl) is not spontaneous. To force this reaction, a positive potential of magnitude greater than the negative cell potential must be applied to the cell.

Figure 17.18 Cells of this sort (a cell for the electrolysis of molten sodium chloride) are used in the Downs process for production of sodium and chlorine, and they typically use iron cathodes and carbon anodes.

The Electrolysis of Water

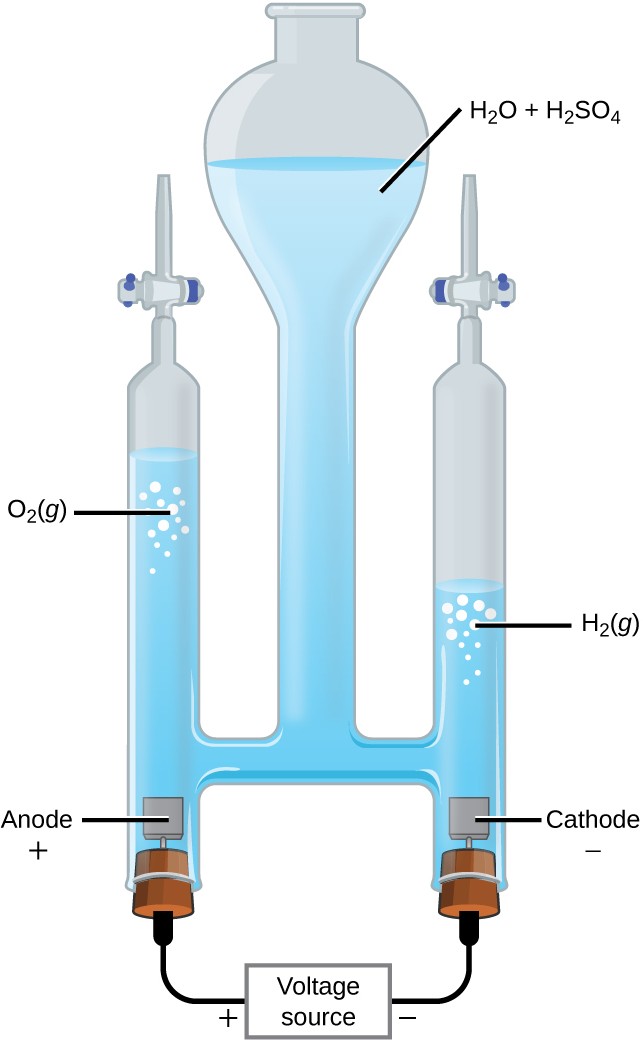

Water may be electrolytically decomposed in a cell similar to the one illustrated in Figure 17.19. To improve electrical conductivity without introducing a different redox species, the hydrogen ion concentration of the water is typically increased by addition of a strong acid. The redox processes associated with this cell are

anode:2H2 O(l) ⟶ O2(g) + 4H+(aq) + 4e− E°anode = +1.229 V

cathode: 2H+(aq) + 2e− ⟶ H2(g) E°cathode = 0 V

cell:2H2 O(l) ⟶ 2H2(g) + O2(g)E°cell = −1.229 V

Again, the cell potential as written is negative, indicating a nonspontaneous cell reaction that must be driven by imposing a cell voltage greater than +1.229 V. Keep in mind that standard electrode potentials are used to inform thermodynamic predictions here, though the cell is not operating under standard state conditions. Therefore, at best, calculated cell potentials should be considered ballpark estimates.

Figure 17.19 The electrolysis of water produces stoichiometric amounts of oxygen gas at the anode and hydrogen at the anode.

The Electrolysis of Aqueous Sodium Chloride

When aqueous solutions of ionic compounds are electrolyzed, the anode and cathode half-reactions may involve the electrolysis of either water species (H2O, H+, OH-) or solute species (the cations and anions of the compound). As an example, the electrolysis of aqueous sodium chloride could involve either of these two anode reactions:

- 2Cl−(aq) ⟶ Cl2(g) + 2 e− E°anode = +1.35827 V

- 2H2 O(l) ⟶ O2(g) + 4H+(aq) + 4e− E°anode = +1.229 V

The standard electrode (reduction) potentials of these two half-reactions indicate water may be oxidized at a less negative/more positive potential (–1.229 V) than chloride ion (–1.358 V). Thermodynamics thus predicts that water would be more readily oxidized, though in practice it is observed that both water and chloride ion are oxidized under typical conditions, producing a mixture of oxygen and chlorine gas.

Turning attention to the cathode, the possibilities for reduction are:

- 2H+(aq) + 2e− ⟶ H2(g) E°cathode = 0 V

- 2H2 O(l) + 2e− ⟶ H2(g) + 2OH−(aq) E°cathode = −0.8277 V

- Na+(aq) + e− ⟶ Na(s)E°cathode= −2.71 V

Comparison of these standard half-reaction potentials suggests the reduction of hydrogen ion is thermodynamically favored. However, in a neutral aqueous sodium chloride solution, the concentration of hydrogen ion is far below the standard state value of 1 M (approximately 10-7 M), and so the observed cathode reaction is actually reduction of water. The net cell reaction in this case is then

cell: 2H2 O(l) + 2Cl−(aq) ⟶ H2(g) + Cl2(g) + 2OH−(aq) E°cell = −2.186 V

This electrolysis reaction is part of the chlor-alkali process used by industry to produce chlorine and sodium hydroxide (lye).

Chemistry in Everyday Life

Electroplating

An important use for electrolytic cells is in electroplating. Electroplating results in a thin coating of one metal on top of a conducting surface. Reasons for electroplating include making the object more corrosion resistant, strengthening the surface, producing a more attractive finish, or for purifying metal. The metals commonly used in electroplating include cadmium, chromium, copper, gold, nickel, silver, and tin. Common consumer products include silver-plated or gold-plated tableware, chrome-plated automobile parts, and jewelry. The silver plating of eating utensils is used here to illustrate the process. (Figure 17.20).

Figure 17.20 This schematic shows an electrolytic cell for silver plating eating utensils.

In the figure, the anode consists of a silver electrode, shown on the left. The cathode is located on the right and is the spoon, which is made from inexpensive metal. Both electrodes are immersed in a solution of silver nitrate. Applying a sufficient potential results in the oxidation of the silver anode

anode: Ag(s) ⟶ Ag+(aq) + e−

and reduction of silver ion at the (spoon) cathode:

cathode: Ag+(aq) + e− ⟶ Ag(s)

The net result is the transfer of silver metal from the anode to the cathode. Several experimental factors must

be carefully controlled to obtain high-quality silver coatings, including the exact composition of the electrolyte solution, the cell voltage applied, and the rate of the electrolysis reaction (electrical current).

Quantitative Aspects of Electrolysis

Electrical current is defined as the rate of flow for any charged species. Most relevant to this discussion is the flow of electrons. Current is measured in a composite unit called an ampere, defined as one coulomb per second (A = 1 C/s). The charge transferred, Q, by passage of a constant current, I, over a specified time interval, t, is then given by the simple mathematical product

Q = It

When electrons are transferred during a redox process, the stoichiometry of the reaction may be used to derive the total amount of (electronic) charge involved. For example, the generic reduction process

Mn+(aq) + ne− ⟶ M(s)

involves the transfer of n mole of electrons. The charge transferred is, therefore,

Q = nF

where F is Faraday’s constant, the charge in coulombs for one mole of electrons. If the reaction takes place in an electrochemical cell, the current flow is conveniently measured, and it may be used to assist in stoichiometric calculations related to the cell reaction.

Example 17.9

Converting Current to Moles of Electrons

In one process used for electroplating silver, a current of 10.23 A was passed through an electrolytic cell for exactly 1 hour. How many moles of electrons passed through the cell? What mass of silver was deposited at the cathode from the silver nitrate solution?

Solution

Faraday’s constant can be used to convert the charge (Q) into moles of electrons (n). The charge is the current (I) multiplied by the time

[latex]n = \frac{Q}{F} = \frac{\frac{10.23 C}{s} \times 1 hr \times \frac{60 min}{hr} \times \frac{60s}{min}}{96,485 C/mol \; e^{-}} = \frac{36,830 C}{96,485 C/mol \; e^{-}} = 0.3817 mol \; e^{-}[/latex]

From the problem, the solution contains AgNO3, so the reaction at the cathode involves 1 mole of electrons

for each mole of silver

cathode: Ag+(aq) + e− ⟶ Ag(s)

The atomic mass of silver is 107.9 g/mol, so

[latex]mass \; Ag = 0.3817 mol \; e^{-} \times \frac{1 mol \; Ag}{1 mol \; e^{-}} \times \frac{107.9g \; Ag}{1 mol \; Ag} = 41.19g \; Ag[/latex]

Check Your Learning

Aluminum metal can be made from aluminum(III) ions by electrolysis. What is the half-reaction at the cathode? What mass of aluminum metal would be recovered if a current of 25.0 A passed through the solution for 15.0 minutes?

Answer: Al3+(aq) + 3 e− ⟶ Al(s); 0.0777 mol Al = 2.10 g Al.

Example 17.10

Time Required for Deposition

In one application, a 0.010-mm layer of chromium must be deposited on a part with a total surface area of 3.3 m2 from a solution of containing chromium(III) ions. How long would it take to deposit the layer of chromium if the current was 33.46 A? The density of chromium (metal) is 7.19 g/cm3.

Solution

First, compute the volume of chromium that must be produced (equal to the product of surface area and thickness):

[latex]volume = (0.010 mm \times \frac{1cm}{10mm}) \times (3.3m^{2} \times (\frac{10,000cm^{2}}{1m^{2}})) = 33cm^{3}[/latex]

Use the computed volume and the provided density to calculate the molar amount of chromium required:

[latex]mass = volume \times density = 33cm^{3} \times \frac{7.19g}{cm^{3}} = 237g \; Cr[/latex]

[latex]mol Cr = 237 g \; Cr \times \frac{1 mol \; Cr}{ 52.00g \; Cr} = 4.56 mol \; Cr[/latex]

The stoichiometry of the chromium(III) reduction process requires three moles of electrons for each mole of chromium(0) produced, and so the total charge required is:

[latex]Q = 4.56 mol \; Cr \times \frac{3mol \; e^{-}}{1 mol \; Cr} \times \frac{96,485C}{mol \; e^{-}} = 1.32\times 10^{6}C[/latex]

Finally, if this charge is passed at a rate of 33.46 C/s, the required time is:

[latex]t=\frac{Q}{I} = \frac{1.32 \times 10^{6}C}{33.46C/s} = 3.95 \times 10^{4}s = 11.0hr[/latex]

Check Your Learning

What mass of zinc is required to galvanize the top of a 3.00 m × 5.50 m sheet of iron to a thickness of 0.100 mm of zinc? If the zinc comes from a solution of Zn(NO3)2 and the current is 25.5 A, how long will it take to galvanize the top of the iron? The density of zinc is 7.140 g/cm3.

Answer: 11.8 kg Zn requires 382 hours.

Key Terms

active electrode electrode that participates as a reactant or product in the oxidation-reduction reaction of an electrochemical cell; the mass of an active electrode changes during the oxidation-reduction reaction

alkaline battery primary battery similar to a dry cell that uses an alkaline (often potassium hydroxide) electrolyte; designed to be an improved replacement for the dry cell, but with more energy storage and less electrolyte leakage than typical dry cell

anode electrode in an electrochemical cell at which oxidation occurs

battery single or series of galvanic cells designed for use as a source of electrical power

cathode electrode in an electrochemical cell at which reduction occurs

cathodic protection approach to preventing corrosion of a metal object by connecting it to a sacrificial anode composed of a more readily oxidized metal

cell notation (schematic) symbolic representation of the components and reactions in an electrochemical cell

cell potential (Ecell) difference in potential of the cathode and anode half-cells

concentration cell galvanic cell comprising half-cells of identical composition but for the concentration of one redox reactant or product

corrosion degradation of metal via a natural electrochemical process

dry cell primary battery, also called a zinc-carbon battery, based on the spontaneous oxidation of zinc by manganese(IV)

electrode potential (EX) the potential of a cell in which the half-cell of interest acts as a cathode when connected to the standard hydrogen electrode

electrolysis process using electrical energy to cause a nonspontaneous process to occur

electrolytic cell electrochemical cell in which an external source of electrical power is used to drive an otherwise nonspontaneous process

Faraday’s constant (F) charge on 1 mol of electrons; F = 96,485 C/mol e−

fuel cell devices similar to galvanic cells that require a continuous feed of redox reactants; also called a flow battery

galvanic (voltaic) cell electrochemical cell in which a spontaneous redox reaction takes place; also called a voltaic cell

galvanization method of protecting iron or similar metals from corrosion by coating with a thin layer of more easily oxidized zinc.

half cell component of a cell that contains the redox conjugate pair (“couple”) of a single reactant

inert electrode electrode that conducts electrons to and from the reactants in a half-cell but that is not itself oxidized or reduced

lead acid battery rechargeable battery commonly used in automobiles; it typically comprises six galvanic cells based on Pb half-reactions in acidic solution

lithium ion battery widely used rechargeable battery commonly used in portable electronic devices, based on lithium ion transfer between the anode and cathode

Nernst equation relating the potential of a redox system to its composition

nickel-cadmium battery rechargeable battery based on Ni/Cd half-cells with applications similar to those of lithium ion batteries

primary cell nonrechargeable battery, suitable for single use only

sacrificial anode electrode constructed from an easily oxidized metal, often magnesium or zinc, used to prevent corrosion of metal objects via cathodic protection

salt bridge tube filled with inert electrolyte solution

secondary cell battery designed to allow recharging

standard cell potential (E°cell) the cell potential when all reactants and products are in their standard states (1 bar or 1 atm or gases; 1 M for solutes), usually at 298.15 K

standard electrode potential ( (E°X ) ) electrode potential measured under standard conditions (1 bar or 1 atm for gases; 1 M for solutes) usually at 298.15 K

standard hydrogen electrode (SHE) half-cell based on hydrogen ion production, assigned a potential of exactly 0 V under standard state conditions, used as the universal reference for measuring electrode potential

Key Equations

- E°cell = E°cathode − E°anode

- [latex]E°_{cell} = \frac{RT}{nF}ln K[/latex]

- [latex]E°_{cell} = \frac{0.0257V}{n} ln K = \frac{0.0592V}{n} log K(at 298.15 K)[/latex]

- [latex]E_{cell} = E°_{cell} − \frac{RT}{nF} ln Q(Nernst equation)[/latex]

- [latex]E°_{cell} − \frac{0.0592V}{n} log Q(at 298.15 K)[/latex]

- ΔG = −nFEcell

- ΔG° = −nFE°cell

- wele = wmax = −nFEcell

- Q = I × t = n × F

Summary

Review of Redox Chemistry

Redox reactions are defined by changes in reactant oxidation numbers, and those most relevant to electrochemistry involve actual transfer of electrons. Aqueous phase redox processes often involve water or its characteristic ions, H+ and OH−, as reactants in addition to the oxidant and reductant, and equations representing these reactions can be challenging to balance. The half-reaction method is a systematic approach to balancing such equations that involves separate treatment of the oxidation and reduction half-reactions.

Galvanic Cells

Galvanic cells are devices in which a spontaneous redox reaction occurs indirectly, with the oxidant and reductant redox couples contained in separate half-cells. Electrons are transferred from the reductant (in the anode half-cell) to

the oxidant (in the cathode half-cell) through an external circuit, and inert solution phase ions are transferred between half-cells, through a salt bridge, to maintain charge neutrality. The construction and composition of a galvanic cell may be succinctly represented using chemical formulas and others symbols in the form of a cell schematic (cell notation).

Electrode and Cell Potentials

The property of potential, E, is the energy associated with the separation/transfer of charge. In electrochemistry, the potentials of cells and half-cells are thermodynamic quantities that reflect the driving force or the spontaneity of their redox processes. The cell potential of an electrochemical cell is the difference in between its cathode and anode. To permit easy sharing of half-cell potential data, the standard hydrogen electrode (SHE) is assigned a potential of exactly 0 V and used to define a single electrode potential for any given half-cell. The electrode potential of a half-cell, EX, is the cell potential of said half-cell acting as a cathode when connected to a SHE acting as an anode. When the half-cell is operating under standard state conditions, its potential is the standard electrode potential, E°X. Standard electrode potentials reflect the relative oxidizing strength of the half-reaction’s reactant, with stronger oxidants exhibiting larger (more positive) E°X values. Tabulations of standard electrode potentials may be used to compute standard cell potentials, E°cell, for many redox reactions. The arithmetic sign of a cell potential indicates the spontaneity of the cell reaction, with positive values for spontaneous reactions and negative values for nonspontaneous reactions (spontaneous in the reverse direction).

Potential, Free Energy, and Equilibrium

Potential is a thermodynamic quantity reflecting the intrinsic driving force of a redox process, and it is directly related to the free energy change and equilibrium constant for the process. For redox processes taking place in electrochemical cells, the maximum (electrical) work done by the system is easily computed from the cell potential and the reaction stoichiometry and is equal to the free energy change for the process. The equilibrium constant for a redox reaction is logarithmically related to the reaction’s cell potential, with larger (more positive) potentials indicating reactions with greater driving force that equilibrate when the reaction has proceeded far towards completion (large value of K). Finally, the potential of a redox process varies with the composition of the reaction mixture, being related to the reactions standard potential and the value of its reaction quotient, Q, as described by the Nernst equation.

Batteries and Fuel Cells

Galvanic cells designed specifically to function as electrical power supplies are called batteries. A variety of both single-use batteries (primary cells) and rechargeable batteries (secondary cells) are commercially available to serve a variety of applications, with important specifications including voltage, size, and lifetime. Fuel cells, sometimes called flow batteries, are devices that harness the energy of spontaneous redox reactions normally associated with combustion processes. Like batteries, fuel cells enable the reaction’s electron transfer via an external circuit, but they require continuous input of the redox reactants (fuel and oxidant) from an external reservoir. Fuel cells are typically much more efficient in converting the energy released by the reaction to useful work in comparison to internal combustion engines.

Corrosion

Spontaneous oxidation of metals by natural electrochemical processes is called corrosion, familiar examples including the rusting of iron and the tarnishing of silver. Corrosion process involve the creation of a galvanic cell in which different sites on the metal object function as anode and cathode, with the corrosion taking place at the anodic site. Approaches to preventing corrosion of metals include use of a protective coating of zinc (galvanization) and the use of sacrificial anodes connected to the metal object (cathodic protection).

Electrolysis

Nonspontaneous redox processes may be forced to occur in electrochemical cells by the application of an appropriate potential using an external power source—a process known as electrolysis. Electrolysis is the basis for certain ore refining processes, the industrial production of many chemical commodities, and the electroplating of metal coatings

on various products. Measurement of the current flow during electrolysis permits stoichiometric calculations.

Exercises

Review of Redox Chemistry

- Identify each half-reaction below as either oxidation or reduction.

- Fe3+ + 3e− ⟶ Fe

- Cr ⟶ Cr3+ + 3e−

- MnO4 2− ⟶ MnO4 − + e−

- Li+ + e− ⟶ Li

- Identify each half-reaction below as either oxidation or reduction.

- Cl− ⟶ Cl2

- Mn2+ ⟶ MnO2

- H2 ⟶ H+

- NO3 − ⟶ NO

- Assuming each pair of half-reactions below takes place in an acidic solution, write a balanced equation for the overall reaction.

- Ca ⟶ Ca2+ + 2e−, F2 + 2e− ⟶ 2F−

- Li ⟶ Li+ + e−, Cl2 + 2e− ⟶ 2Cl−

- Fe ⟶ Fe3+ + 3e−, Br2 + 2e− ⟶ 2Br−

- Ag ⟶ Ag+ + e−, MnO4 − + 4H+ + 3e− ⟶ MnO2 + 2H2 O

- Balance the equations below assuming they occur in an acidic solution.

- H2 O2 + Sn2+ ⟶ H2 O + Sn4+

- PbO2 + Hg ⟶ Hg2 2+ + Pb2+

- Al + Cr2 O7 2− ⟶ Al3+ + Cr3+

- Identify the oxidant and reductant of each reaction of the previous exercise.

- Balance the equations below assuming they occur in a basic solution.

- SO3 2−(aq) + Cu(OH)2(s) ⟶ SO4 2−(aq) + Cu(OH)(s)

- O2(g) + Mn(OH)2(s) ⟶ MnO2(s)

- NO3 −(aq) + H2(g) ⟶ NO(g)

- Al(s) + CrO4 2−(aq) ⟶ Al(OH)3(s) + Cr(OH)4 −(aq)

- Identify the oxidant and reductant of each reaction of the previous exercise.

- Why don’t hydroxide ions appear in equations for half-reactions occurring in acidic solution?

- Why don’t hydrogen ions appear in equations for half-reactions occurring in basic solution?

- Why must the charge balance in oxidation-reduction reactions?

Galvanic Cells

- Write cell schematics for the following cell reactions, using platinum as an inert electrode as needed.

- Mg(s) + Ni2+(aq) ⟶ Mg2+(aq) + Ni(s)

- 2Ag+(aq) + Cu(s) ⟶ Cu2+(aq) + 2Ag(s)

- Mn(s) + Sn(NO3 )2(aq) ⟶ Mn(NO3 )2(aq) + Au(s)

- 3CuNO3(aq) + Au(NO3 )3(aq) ⟶ 3Cu(NO3 )2(aq) + Au(s)

- Assuming the schematics below represent galvanic cells as written, identify the half-cell reactions occurring in each.

- Mg(s) │ Mg2+(aq) ║ Cu2+(aq) │ Cu(s)

- Ni(s) │ Ni2+(aq) ║ Ag+(aq) │ Ag(s)

- Write a balanced equation for the cell reaction of each cell in the previous exercise.

- Balance each reaction below, and write a cell schematic representing the reaction as it would occur in a galvanic cell.

- Al(s) + Zr4+(aq) ⟶ Al3+(aq) + Zr(s)

- Ag+(aq) + NO(g) ⟶ Ag(s) + NO3 −(aq)(acidic solution)

- SiO3 2−(aq) + Mg(s) ⟶ Si(s) + Mg(OH)2(s)(basic solution)

- ClO3 −(aq) + MnO2(s) ⟶ Cl−(aq) + MnO4 −(aq)(basic solution)

- Identify the oxidant and reductant in each reaction of the previous exercise.

- From the information provided, use cell notation to describe the following systems:

- In one half-cell, a solution of Pt(NO3)2 forms Pt metal, while in the other half-cell, Cu metal goes into a Cu(NO3)2 solution with all solute concentrations 1 M.

- The cathode consists of a gold electrode in a 0.55 M Au(NO3)3 solution and the anode is a magnesium electrode in 0.75 M Mg(NO3)2 solution.

- One half-cell consists of a silver electrode in a 1 M AgNO3 solution, and in the other half-cell, a copper electrode in 1 M Cu(NO3)2 is oxidized.

- Why is a salt bridge necessary in galvanic cells like the one in Figure17.3?

- An active (metal) electrode was found to gain mass as the oxidation-reduction reaction was allowed to proceed. Was the electrode an anode or a cathode? Explain.

- An active (metal) electrode was found to lose mass as the oxidation-reduction reaction was allowed to proceed. Was the electrode an anode or a cathode? Explain.

- The masses of three electrodes (A, B, and C), each from three different galvanic cells, were measured before and after the cells were allowed to pass current for a while. The mass of electrode A increased, that of electrode B was unchanged, and that of electrode C decreased. Identify each electrode as active or inert, and note (if possible) whether it functioned as anode or cathode.

Electrode and Cell Potentials

- Calculate the standard cell potential for each reaction below, and note whether the reaction is spontaneous under standard state conditions.

- Mg(s) + Ni2+(aq) ⟶ Mg2+(aq) + Ni(s)

- 2Ag+(aq) + Cu(s) ⟶ Cu2+(aq) + 2Ag(s)

- Mn(s) + Sn(NO3 )2(aq) ⟶ Mn(NO3 )2(aq) + Sn(s)

- 3Fe(NO3 )2(aq) + Au(NO3 )3(aq) ⟶ 3Fe(NO3 )3(aq) + Au(s)

- Calculate the standard cell potential for each reaction below, and note whether the reaction is spontaneous under standard state conditions.

- Mn(s) + Ni2+(aq) ⟶ Mn2+(aq) + Ni(s)

- 3Cu2+(aq) + 2Al(s) ⟶ 2Al3+(aq) + 3Cu(s)

- Na(s) + LiNO3(aq) ⟶ NaNO 3(aq) + Li(s)

- Ca(NO3 )2(aq) + Ba(s) ⟶ Ba(NO3 )2(aq) + Ca(s)

- Write the balanced cell reaction for the cell schematic below, calculate the standard cell potential, and note whether the reaction is spontaneous under standard state conditions.

Cu(s) │ Cu2+(aq) ║ Au3+(aq) │ Au(s)

- Determine the cell reaction and standard cell potential at 25 °C for a cell made from a cathode half-cell consisting of a silver electrode in 1 M silver nitrate solution and an anode half-cell consisting of a zinc electrode in 1 M zinc nitrate. Is the reaction spontaneous at standard conditions?

- Determine the cell reaction and standard cell potential at 25 °C for a cell made from an anode half-cell containing a cadmium electrode in 1 M cadmium nitrate and an anode half-cell consisting of an aluminum electrode in 1 M aluminum nitrate solution. Is the reaction spontaneous at standard conditions?

- Write the balanced cell reaction for the cell schematic below, calculate the standard cell potential, and note whether the reaction is spontaneous under standard state conditions.

Pt(s) │ H2(g) │ H+(aq) ║ Br2(aq), Br−(aq) │ Pt(s)

Potential, Free Energy, and Equilibrium

- For each pair of standard cell potential and electron stoichiometry values below, calculate a corresponding standard free energy change (kJ).

- 0.000 V, n = 2

- +0.434 V, n = 2

- −2.439 V, n = 1

- For each pair of standard free energy change and electron stoichiometry values below, calculate a corresponding standard cell potential.

- 12 kJ/mol, n = 3

- −45 kJ/mol, n = 1

- Determine the standard cell potential and the cell potential under the stated conditions for the electrochemical reactions described here. State whether each is spontaneous or nonspontaneous under each set of conditions at 298.15 K.

- Hg(l) + S2−(aq, 0.10 M) + 2Ag+(aq, 0.25 M) ⟶ 2Ag(s) + HgS(s)

- The cell made from an anode half-cell consisting of an aluminum electrode in 0.015 M aluminum nitrate solution and a cathode half-cell consisting of a nickel electrode in 0.25 M nickel(II) nitrate solution.

- The cell made of a half-cell in which 1.0 M aqueous bromide is oxidized to 0.11 M bromine ion and a half-cell in which aluminum ion at 0.023 M is reduced to aluminum metal.

- Determine ΔG and ΔG° for each of the reactions in the previous problem.

- Use the data in Appendix L to calculate equilibrium constants for the following reactions. Assume 298.15 K if no temperature is given.

- AgCl(s) ⇌ Ag+(aq) + Cl−(aq)

- CdS(s) ⇌ Cd2+(aq) + S2−(aq)at 377 K

- Hg2+(aq) + 4Br−(aq) ⇌ [HgBr4]2−(aq)

- H2 O(l) ⇌ H+(aq) + OH−(aq)at 25 °C

Batteries and Fuel Cells

- Consider a battery made from one half-cell that consists of a copper electrode in 1 M CuSO4 solution and another half-cell that consists of a lead electrode in 1 M Pb(NO3)2 solution.

- What is the standard cell potential for the battery?

- What are the reactions at the anode, cathode, and the overall reaction?

- Most devices designed to use dry-cell batteries can operate between 1.0 and 1.5 V. Could this cell be used to make a battery that could replace a dry-cell battery? Why or why not.

- Suppose sulfuric acid is added to the half-cell with the lead electrode and some PbSO4(s) forms. Would the cell potential increase, decrease, or remain the same?

- Consider a battery with the overall reaction: Cu(s) + 2Ag+(aq) ⟶ 2Ag(s) + Cu2+(aq).

- What is the reaction at the anode and cathode?

- A battery is “dead” when its cell potential is zero. What is the value of Q when this battery is dead?

- If a particular dead battery was found to have [Cu2+] = 0.11 M, what was the concentration of silver ion?

- Why do batteries go dead, but fuel cells do not?

- Use the Nernst equation to explain the drop in voltage observed for some batteries as they discharge.

- Using the information thus far in this chapter, explain why battery-powered electronics perform poorly in low temperatures.

Corrosion

- Which member of each pair of metals is more likely to corrode (oxidize)?

- Mg or Ca

- Au or Hg

- Fe or Zn

- Ag or Pt

- Consider the following metals: Ag, Au, Mg, Ni, and Zn. Which of these metals could be used as a sacrificial anode in the cathodic protection of an underground steel storage tank? Steel is an alloy composed mostly of iron, so use −0.447 V as the standard reduction potential for steel.

- Aluminum (E°Al3+ /Al = −2.07 V) is more easily oxidized than iron (E°Fe3+ /Fe = −0.477 V), and yet when both are exposed to the environment, untreated aluminum has very good corrosion resistance while the corrosion resistance of untreated iron is poor. What might explain this observation?

- If a sample of iron and a sample of zinc come into contact, the zinc corrodes but the iron does not. If a sample of iron comes into contact with a sample of copper, the iron corrodes but the copper does not. Explain this phenomenon.

- Suppose you have three different metals, A, B, and C. When metals A and B come into contact, B corrodes and A does not corrode. When metals A and C come into contact, A corrodes and C does not corrode. Based on this information, which metal corrodes and which metal does not corrode when B and C come into contact?

- Why would a sacrificial anode made of lithium metal be a bad choice

Electrolysis

- If a 2.5 A current flows through a circuit for 35 minutes, how many coulombs of charge moved through the circuit?

- For the scenario in the previous question, how many electrons moved through the circuit?

- Write the half-reactions and cell reaction occurring during electrolysis of each molten salt below.

- CaCl2

- LiH

- AlCl3

- CrBr3

- What mass of each product is produced in each of the electrolytic cells of the previous problem if a total charge of 3.33 × 105 C passes through each cell?

- How long would it take to reduce 1 mole of each of the following ions using the current indicated?

- Al3+, 1.234 A

- Ca2+, 22.2 A

- Cr5+, 37.45 A

- Au3+, 3.57 A

- A current of 2.345 A passes through the cell shown in Figure 17.19for 45 minutes. What is the volume of the hydrogen collected at room temperature if the pressure is exactly 1 atm? (Hint: Is hydrogen the only gas present above the water?)

- An irregularly shaped metal part made from a particular alloy was galvanized with zinc using a Zn(NO3)2 solution. When a current of 2.599 A was used, it took exactly 1 hour to deposit a 0.01123-mm layer of zinc on the part. What was the total surface area of the part? The density of zinc is 7.140 g/cm3.