Free Energy (16.4)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define Gibbs free energy, and describe its relation to spontaneity

- Calculate free energy change for a process using free energies of formation for its reactants and products

- Calculate free energy change for a process using enthalpies of formation and the entropies for its reactants and products

- Explain how temperature affects the spontaneity of some processes

- Relate standard free energy changes to equilibrium constants

One of the challenges of using the second law of thermodynamics to determine if a process is spontaneous is that it requires measurements of the entropy change for the system and the entropy change for the surroundings. An alternative approach involving a new thermodynamic property defined in terms of system properties only was introduced in the late nineteenth century by American mathematician Josiah Willard Gibbs. This new property is called the Gibbs free energy (G) (or simply the free energy), and it is defined in terms of a system’s enthalpy and entropy as the following:

G = H − TS

Free energy is a state function, and at constant temperature and pressure, the free energy change (ΔG) may be expressed as the following:

ΔG = ΔH − TΔS

(For simplicity’s sake, the subscript “sys” will be omitted henceforth.)

The relationship between this system property and the spontaneity of a process may be understood by recalling the previously derived second law expression:

ΔSuniv = ΔS + [latex]\frac{q_{\text{surr}}}{T}[/latex]

The first law requires that qsurr = −qsys, and at constant pressure qsys = ΔH, so this expression may be rewritten as:

ΔSuniv = ΔS − [latex]\frac{{\Delta}H}{T}[/latex]

Multiplying both sides of this equation by −T, and rearranging yields the following:

−TΔSuniv = ΔH − TΔS

Comparing this equation to the previous one for free energy change shows the following relation:

ΔG = −TΔSuniv

The free energy change is therefore a reliable indicator of the spontaneity of a process, being directly related to the previously identified spontaneity indicator, ΔSuniv. Table 16.3 summarizes the relation between the spontaneity of a process and the arithmetic signs of these indicators.

Relation between Process Spontaneity and Signs of Thermodynamic Properties

|

ΔSuniv > 0 |

ΔG < 0 |

spontaneous |

|

ΔSuniv < 0 |

ΔG > 0 |

nonspontaneous |

|

ΔSuniv = 0 |

ΔG = 0 |

at equilibrium |

Table 16.3

What’s “Free” about ΔG?

In addition to indicating spontaneity, the free energy change also provides information regarding the amount of useful work (w) that may be accomplished by a spontaneous process. Although a rigorous treatment of this subject is beyond the scope of an introductory chemistry text, a brief discussion is helpful for gaining a better perspective on this important thermodynamic property.

For this purpose, consider a spontaneous, exothermic process that involves a decrease in entropy. The free energy, as defined by

ΔG = ΔH − TΔS

may be interpreted as representing the difference between the energy produced by the process, ΔH, and the energy lost to the surroundings, TΔS. The difference between the energy produced and the energy lost is the energy available (or “free”) to do useful work by the process, ΔG. If the process somehow could be made to take place under conditions of thermodynamic reversibility, the amount of work that could be done would be maximal:

ΔG = wmax

However, as noted previously in this chapter, such conditions are not realistic. In addition, the technologies used to extract work from a spontaneous process (e.g., automobile engine, steam turbine) are never 100% efficient, and so the work done by these processes is always less than the theoretical maximum. Similar reasoning may be applied to a nonspontaneous process, for which the free energy change represents the minimum amount of work that must be done

on the system to carry out the process.

Calculating Free Energy Change

Free energy is a state function, so its value depends only on the conditions of the initial and final states of the system. A convenient and common approach to the calculation of free energy changes for physical and chemical reactions is by use of widely available compilations of standard state thermodynamic data. One method involves the use of standard enthalpies and entropies to compute standard free energy changes, ΔG°, according to the following relation.

ΔG° = ΔH° − TΔS°

Example 16.7

Using Standard Enthalpy and Entropy Changes to Calculate ΔG°

Use standard enthalpy and entropy data from Appendix G to calculate the standard free energy change for the vaporization of water at room temperature (298 K). What does the computed value for ΔG° say about the spontaneity of this process?

Solution

The process of interest is the following:

H2O(l) ⟶ H2O(g)

The standard change in free energy may be calculated using the following equation:

ΔG° = ΔH° − TΔS°

From Appendix G:

|

Substance |

ΔH°f (kJ/mol) |

S°(J/K·mol) |

|

H2O(l) |

−286.83 |

70.0 |

|

H2O(g) |

−241.82 |

188.8 |

Using the appendix data to calculate the standard enthalpy and entropy changes yields:

ΔH° = ΔH°f (H20(g)) - ΔH°f (H20(l))

= [-241.82 kJ/mol - (-286.83)]kJ/mol = 45.01 kJ

ΔS° = 1 mol x S°(H2O(g)) - 1 mol x S°(H2O(l))

= (1 mol)188.8 J/mol·K - (1 mol)70.0 J/mol K = 118.8 J/K

ΔG° = ΔH° − TΔS°

Substitution into the standard free energy equation yields:

ΔG° = ΔH° − TΔS°

= 45.01 kJ - (298 K x 118.8 J/K) x [latex]\frac{1 \text{kJ}}{1000 \text{J}}[/latex]

45.01 kJ - 35.4 kJ = 9.6 kJ

At 298 K (25 °C) ΔG° > 0, so boiling is nonspontaneous (not spontaneous).

Check Your Learning

Use standard enthalpy and entropy data from Appendix G to calculate the standard free energy change for the reaction shown here (298 K). What does the computed value for ΔG° say about the spontaneity of this process?

C2H6(g) ⟶ H2(g) + C2H4(g)

Answer: ΔG° = 102.0 kJ/mol; the reaction is nonspontaneous (not spontaneous) at 25 °C.

The standard free energy change for a reaction may also be calculated from standard free energy of formation ΔGf° values of the reactants and products involved in the reaction. The standard free energy of formation is the free energy change that accompanies the formation of one mole of a substance from its elements in their standard states. Similar to the standard enthalpy of formation, ΔG°f is by definition zero for elemental substances under standard state conditions. The approach used to calculate ΔG° for a reaction from ΔG°f previously for enthalpy and entropy changes. For the reaction

mA + nB ⟶ xC + yD,

the standard free energy change at room temperature may be calculated as

ΔG° = ∑ ν ΔG°(products) − ∑ ν ΔG°(reactants)

= [xΔG°f (C) + yΔG°f (D)] - [mΔG°f (A) + nΔG°f (B)]

Example 16.8

Using Standard Free Energies of Formation to Calculate ΔG°

Consider the decomposition of yellow mercury(II) oxide.

HgO(s, yellow) ⟶ Hg(l) + [latex]\frac{1}{2}[/latex]O2(g)

Calculate the standard free energy change at room temperature, ΔG°, using (a) standard free energies of formation and (b) standard enthalpies of formation and standard entropies. Do the results indicate the reaction to be spontaneous or nonspontaneous under standard conditions?

Solution

The required data are available in Appendix G and are shown here.

|

Compound |

ΔG°f(kJ/mol) |

ΔH°f(kJ/mol) |

S° (J/K·mol) |

|

HgO (s, yellow) |

−58.43 |

−90.46 |

71.13 |

|

Hg(l) |

0 |

0 |

75.9 |

|

O2(g) |

0 |

0 |

205.2 |

(a) Using free energies of formation:

ΔG° = ∑ νGS°f (products) − ∑ νΔG°f (reactants)

= [1ΔG°f Hg(l) + [latex]\frac{1}{2}[/latex]ΔG°f ] - 1ΔG°f HgO(s, yellow)

= [1 mol(0 kJ/mol) + [latex]\frac{1}{2}[/latex] mol(0 kJ/mol)] - 1 mol( 58.43 kJ/mol) = 58.43 kJ/mol

(b) Using enthalpies and entropies of formation:

ΔG° = ∑ νH°f (products) − ∑ νΔH°f (reactants)

= [1ΔH°f Hg(l) + [latex]\frac{1}{2}[/latex]ΔG°f ] - 1ΔH°f HgO(s, yellow)

= [1 mol(0 kJ/mol) + [latex]\frac{1}{2}[/latex] mol(0 kJ/mol)] - 1 mol( 90.46 kJ/mol) = 90.46 kJ/mol

ΔS° = ∑ νS°f (products) − ∑ νΔS°f (reactants)

= [1ΔS°Hg(l) + [latex]\frac{1}{2}[/latex] S°O2(g)] - 1ΔS°HgO(s, yellow)

= [ 1 mol (75.9 J/mol K) + [latex]\frac{1}{2}[/latex] mol(205.2 J/mol K)] - 1 mol(71.13 J/mol K) = 107.4 J/mol K

ΔG° = ΔH° − TΔS° = 90.46 kJ - 298.15 K x 107.4 J/K·mol x [latex]\frac{1\text{kJ}}{1000 \text{J}}[/latex]

ΔG° = (90.46 - 32.01) kJ/mol = 58.45 kJ/mol

Both ways to calculate the standard free energy change at 25 °C give the same numerical value (to three significant figures), and both predict that the process is nonspontaneous (not spontaneous) at room temperature.

Check Your Learning

Calculate ΔG° using (a) free energies of formation and (b) enthalpies of formation and entropies (Appendix G). Do the results indicate the reaction to be spontaneous or nonspontaneous at 25 °C?

C2H4(g) ⟶ H2(g) + C2H2(g)

Answer: (a) 140.8 kJ/mol, nonspontaneous (b) 141.5 kJ/mol, nonspontaneous

Free Energy Changes for Coupled Reactions

The use of free energies of formation to compute free energy changes for reactions as described above is possible because ΔG is a state function, and the approach is analogous to the use of Hess’ Law in computing enthalpy changes (see the chapter on thermochemistry). Consider the vaporization of water as an example:

H2O(l) → H2O(g)

An equation representing this process may be derived by adding the formation reactions for the two phases of water (necessarily reversing the reaction for the liquid phase). The free energy change for the sum reaction is the sum of free energy changes for the two added reactions:

H2(g) + [latex]\frac{1}{2}[/latex]O2(g) → H2O(g) ΔG°f gas

H2O(l) → H2(g) + [latex]\frac{1}{2}[/latex]O2(g) -ΔG°f liquid

H2O(l) → H2O(g) ΔG° = ΔG°f gas - ΔG°f liquid

This approach may also be used in cases where a nonspontaneous reaction is enabled by coupling it to a spontaneous reaction. For example, the production of elemental zinc from zinc sulfide is thermodynamically unfavorable, as indicated by a positive value for ΔG°:

ZnS(s) → Zn(s) + S(s) ΔG°1 = 201.3 kJ

The industrial process for production of zinc from sulfidic ores involves coupling this decomposition reaction to the thermodynamically favorable oxidation of sulfur:

S(s) + O2(g) → SO2(g) ΔG°2 = -300.1 kJ

The coupled reaction exhibits a negative free energy change and is spontaneous:

ZnS(s) + O2(g) → Zn(s) + SO2(g) ΔG ° = 201.3 kJ + − 300.1 kJ = 98.8 kJ

This process is typically carried out at elevated temperatures, so this result obtained using standard free energy values is just an estimate. The gist of the calculation, however, holds true.

Example 16.9

Calculating Free Energy Change for a Coupled Reaction

Is a reaction coupling the decomposition of ZnS to the formation of H2S expected to be spontaneous under standard conditions?

Solution

Following the approach outlined above and using free energy values from Appendix G:

Decomposition of zinc sulfide: ZnS(s) → Zn(s) + S(s) ΔG°1 = 201.3 kJ

Formation of hydrogen sulfide: S(s) + H2(g) → H2S(g) ΔG°2 = − 33.4 kJ

Coupled reaction: ZnS(s) + H2(g) → Zn(s) + H2S(g) ΔG° = 201.3 kJ + − 33.4 kJ = 167.9 kJS(s)

The coupled reaction exhibits a positive free energy change and is thus nonspontaneous.

Check Your Learning

What is the standard free energy change for the reaction below? Is the reaction expected to be spontaneous under standard conditions?

FeS(s) + O2(g) → Fe(s) + SO2(g)

Answer: −199.7 kJ; spontaneous

Temperature Dependence of Spontaneity

As was previously demonstrated in this chapter’s section on entropy, the spontaneity of a process may depend upon the temperature of the system. Phase transitions, for example, will proceed spontaneously in one direction or the other depending upon the temperature of the substance in question. Likewise, some chemical reactions can also exhibit temperature dependent spontaneities. To illustrate this concept, the equation relating free energy change to the enthalpy and entropy changes for the process is considered:

ΔG = ΔH − TΔS

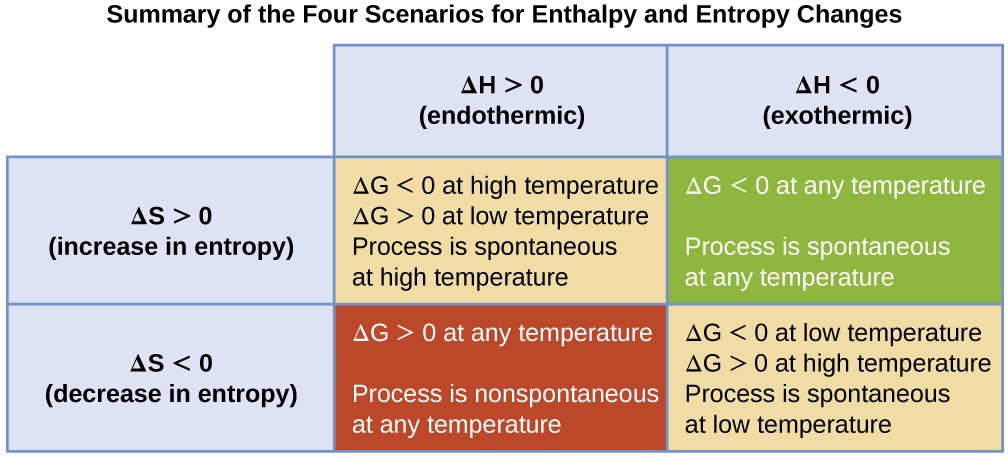

The spontaneity of a process, as reflected in the arithmetic sign of its free energy change, is then determined by the signs of the enthalpy and entropy changes and, in some cases, the absolute temperature. Since T is the absolute (kelvin) temperature, it can only have positive values. Four possibilities therefore exist with regard to the signs of the enthalpy and entropy changes:

- Both ΔH and ΔS are positive. This condition describes an endothermic process that involves an increase in system entropy. In this case, ΔG will be negative if the magnitude of the TΔS term is greater than ΔH. If the TΔS term is less than ΔH, the free energy change will be positive. Such a process is spontaneous at high temperatures and nonspontaneous at low temperatures.

- Both ΔH and ΔS are negative. This condition describes an exothermic process that involves a decrease in system entropy. In this case, ΔG will be negative if the magnitude of the TΔS term is less than ΔH. If the TΔS term’s magnitude is greater than ΔH, the free energy change will be positive. Such a process is spontaneous at low temperatures and nonspontaneous at high temperatures.

- ΔH is positive and ΔS is negative. This condition describes an endothermic process that involves a decrease in system entropy. In this case, ΔG will be positive regardless of the temperature. Such a process is nonspontaneous at all temperatures.

- ΔH is negative and ΔS is positive. This condition describes an exothermic process that involves an increase in system entropy. In this case, ΔG will be negative regardless of the temperature. Such a process is spontaneous at all temperatures.

These four scenarios are summarized in Figure 16.12.

Figure 16.12 There are four possibilities regarding the signs of enthalpy and entropy changes.

Example 16.10

Predicting the Temperature Dependence of Spontaneity

The incomplete combustion of carbon is described by the following equation:

2C(s) + O2(g) ⟶ 2CO(g)

How does the spontaneity of this process depend upon temperature?

Solution

Combustion processes are exothermic (ΔH < 0). This particular reaction involves an increase in entropy due to the accompanying increase in the amount of gaseous species (net gain of one mole of gas, ΔS > 0). The reaction is therefore spontaneous (ΔG < 0) at all temperatures.

Check Your Learning

Popular chemical hand warmers generate heat by the air-oxidation of iron:

4Fe(s) + 3O2(g) ⟶ 2Fe2 O3(s)

How does the spontaneity of this process depend upon temperature?

Answer: ΔH and ΔS are negative; the reaction is spontaneous at low temperatures.

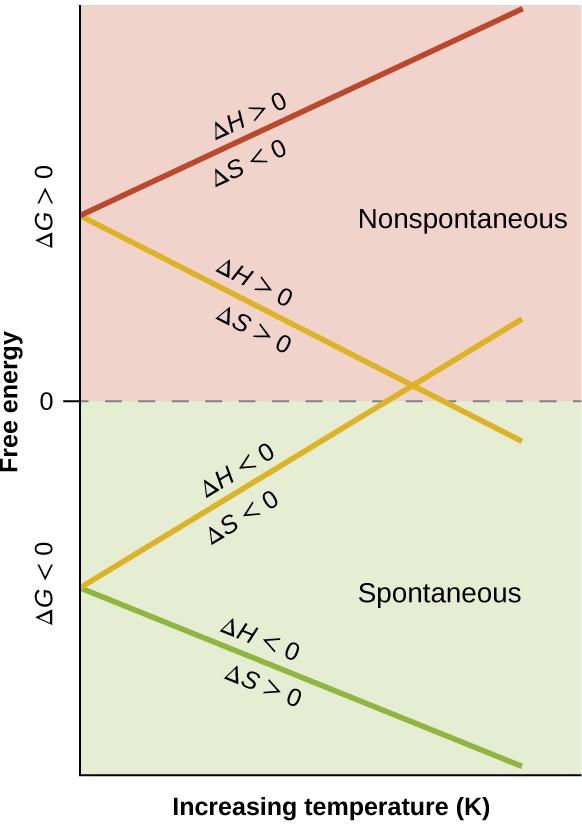

When considering the conclusions drawn regarding the temperature dependence of spontaneity, it is important to keep in mind what the terms “high” and “low” mean. Since these terms are adjectives, the temperatures in question are deemed high or low relative to some reference temperature. A process that is nonspontaneous at one temperature but spontaneous at another will necessarily undergo a change in “spontaneity” (as reflected by its ΔG) as temperature varies. This is clearly illustrated by a graphical presentation of the free energy change equation, in which ΔG is plotted on the y axis versus T on the x axis:

ΔG = ΔH − TΔS

y = b + mx

Such a plot is shown in Figure 16.13. A process whose enthalpy and entropy changes are of the same arithmetic sign will exhibit a temperature-dependent spontaneity as depicted by the two yellow lines in the plot. Each line crosses from one spontaneity domain (positive or negative ΔG) to the other at a temperature that is characteristic of the process in question. This temperature is represented by the x-intercept of the line, that is, the value of T for which ΔG is zero:

ΔG = 0 = ΔH − TΔS

T = [latex]\frac{\Delta \text{H}}{\Delta \text{S}}[/latex]

So, saying a process is spontaneous at “high” or “low” temperatures means the temperature is above or below, respectively, that temperature at which ΔG for the process is zero. As noted earlier, the condition of ΔG = 0 describes a system at equilibrium.

Figure 16.13 These plots show the variation in ΔG with temperature for the four possible combinations of arithmetic sign for ΔH and ΔS.

Example 16.11

Equilibrium Temperature for a Phase Transition

As defined in the chapter on liquids and solids, the boiling point of a liquid is the temperature at which its liquid and gaseous phases are in equilibrium (that is, when vaporization and condensation occur at equal rates). Use the information in Appendix G to estimate the boiling point of water.

Solution

The process of interest is the following phase change:

H2O(l) ⟶ H2O(g)

When this process is at equilibrium, ΔG = 0, so the following is true:

0 = ΔH° − TΔS° or T = [latex]\frac{\Delta \text{H°}}{\Delta \text{S°}}[/latex]

Using the standard thermodynamic data from Appendix G,

ΔH° = 1 mol × ΔH°f (H2 O(g)) − 1 mol × ΔH°f (H2O(l))

= (1 mol) − 241.82 kJ/mol − (1 mol)(−286.83 kJ/mol) = 44.01 kJ

ΔS° = 1 mol × ΔS°(H2O(g)) − 1 mol × ΔS°(H2O(l))

= (1 mol) 188.8 J/K·mol − (1 mol) 70.0 J/K·mol = 118.8 J/K

T = [latex]\frac{\Delta \text{H°}}{\Delta \text{S°}} = \frac{44.01 \times 10^{3} \text{J}}{118.8 \text{J/K}}[/latex] = 370.5 K = 97.3 °C

The accepted value for water’s normal boiling point is 373.2 K (100.0 °C), and so this calculation is in reasonable agreement. Note that the values for enthalpy and entropy changes data used were derived from standard data at 298 K (Appendix G). If desired, you could obtain more accurate results by using enthalpy and entropy changes determined at (or at least closer to) the actual boiling point.

Check Your Learning

Use the information in Appendix G to estimate the boiling point of CS2.

Answer: 313 K (accepted value 319 K)

Free Energy and Equilibrium

The free energy change for a process may be viewed as a measure of its driving force. A negative value for ΔG represents a driving force for the process in the forward direction, while a positive value represents a driving force for the process in the reverse direction. When ΔG is zero, the forward and reverse driving forces are equal, and the process occurs in both directions at the same rate (the system is at equilibrium).

In the chapter on equilibrium the reaction quotient, Q, was introduced as a convenient measure of the status of an equilibrium system. Recall that Q is the numerical value of the mass action expression for the system, and that you may use its value to identify the direction in which a reaction will proceed in order to achieve equilibrium. When Q is lesser than the equilibrium constant, K, the reaction will proceed in the forward direction until equilibrium is reached and Q = K. Conversely, if Q > K, the process will proceed in the reverse direction until equilibrium is achieved.

The free energy change for a process taking place with reactants and products present under nonstandard conditions (pressures other than 1 bar; concentrations other than 1 M) is related to the standard free energy change according to this equation:

ΔG = ΔG° + RT ln Q

R is the gas constant (8.314 J/K mol), T is the kelvin or absolute temperature, and Q is the reaction quotient. This equation may be used to predict the spontaneity for a process under any given set of conditions as illustrated in Example 16.12.

Example 16.12

Calculating ΔG under Nonstandard Conditions

What is the free energy change for the process shown here under the specified conditions?

T = 25 °C, [latex]P_{N_{2}}[/latex] = 0.870 atm, [latex]P_{H_{2}}[/latex] = 0.250 atm, and [latex]P_{NH_{3}}[/latex] = 12.9 atm

2NH3(g) ⟶ 3H2(g) + N2(g) ΔG° = 33.0 kJ/mol

Solution

The equation relating free energy change to standard free energy change and reaction quotient may be used directly:

ΔG = ΔG° + RT ln Q = 33.0 [latex]\frac{\text{kJ}}{\text{mol}}[/latex] + (8.314 [latex]\frac{\text{J}}{ \text{mol K}} \times 298K \times \text{ln} \frac{(0.250^{3}) \times 0.870}{12.9^2}[/latex])

= 9680 [latex]\frac{\text{J}}{\text{mol}}[/latex] or 9.68 kJ/mol

Since the computed value for ΔG is positive, the reaction is nonspontaneous under these conditions.

Check Your Learning

Calculate the free energy change for this same reaction at 875 °C in a 5.00 L mixture containing 0.100 mol of each gas. Is the reaction spontaneous under these conditions?

Answer: ΔG = −47 kJ; yes

For a system at equilibrium, Q = K and ΔG = 0, and the previous equation may be written as

0 = ΔG° + RT ln K (at equilibrium)

ΔG° = −RT ln K or K = [latex]e^{ - \frac{\Delta \text{G}}{\text{RT}}}[/latex]

This form of the equation provides a useful link between these two essential thermodynamic properties, and it can be used to derive equilibrium constants from standard free energy changes and vice versa. The relations between standard free energy changes and equilibrium constants are summarized in Table 16.4.

Relations between Standard Free Energy Changes and Equilibrium Constants

|

K |

ΔG° |

Composition of an Equilibrium Mixture |

|

> 1 |

< 0 |

Products are more abundant |

|

< 1 |

> 0 |

Reactants are more abundant |

|

= 1 |

= 0 |

Reactants and products are comparably abundant |

Table 16.4

Example 16.13

Calculating an Equilibrium Constant using Standard Free Energy Change

Given that the standard free energies of formation of Ag+(aq), Cl−(aq), and AgCl(s) are 77.1 kJ/mol, −131.2 kJ/mol, and −109.8 kJ/mol, respectively, calculate the solubility product, Ksp, for AgCl.

Solution

The reaction of interest is the following:

AgCl(s) ⇌ Ag+(aq) + Cl−(aq) Ksp = [Ag+][Cl−]

The standard free energy change for this reaction is first computed using standard free energies of formation for its reactants and products:

ΔG° = [ΔG°f (Ag+(aq)) + ΔG°f (Cl-(aq))] - [ΔG°f (AgCl(s))]

= [77.1 kJ/mol - 131.2 kJ/mol] - [-109.8 kJ/mol] = 55.7 kJ/mol

The equilibrium constant for the reaction may then be derived from its standard free energy change:

[latex]k_{sp} = e^{-\frac{\Delta G°}{RT}} = exp(-\frac{\Delta G°}{RT}) = exp(-\frac{55.7\times10^3 J/mol}{8.314 J/mol * K \times 298.15K}) = exp(-22.470) = e^{-22.470} = 1.74 \times 10^{-10}[/latex]

This result is in reasonable agreement with the value provided in Appendix J.

Check Your Learning

Use the thermodynamic data provided in Appendix G to calculate the equilibrium constant for the dissociation of dinitrogen tetroxide at 25 °C.

2NO2(g) ⇌ N2O4(g)

Answer: K = 6.9

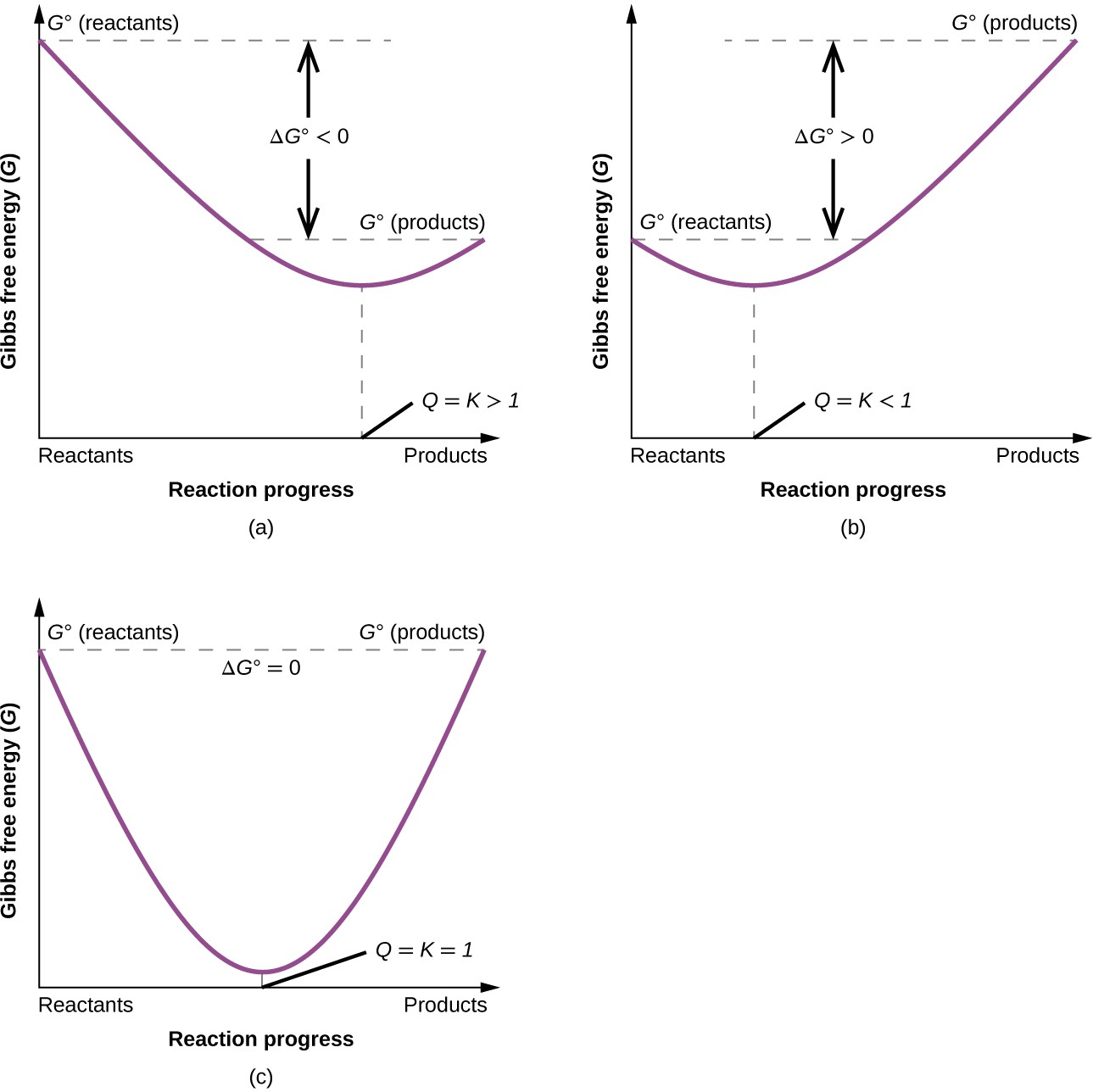

To further illustrate the relation between these two essential thermodynamic concepts, consider the observation that reactions spontaneously proceed in a direction that ultimately establishes equilibrium. As may be shown by plotting the free energy change versus the extent of the reaction (for example, as reflected in the value of Q), equilibrium is established when the system’s free energy is minimized (Figure 16.14). If a system consists of reactants and products in nonequilibrium amounts (Q ≠ K), the reaction will proceed spontaneously in the direction necessary to establish equilibrium.

Figure 16.14 These plots show the free energy versus reaction progress for systems whose standard free energy changes are (a) negative, (b) positive, and (c) zero. Nonequilibrium systems will proceed spontaneously in whatever direction is necessary to minimize free energy and establish equilibrium.

Key Terms

entropy (S) state function that is a measure of the matter and/or energy dispersal within a system, determined by the number of system microstates; often described as a measure of the disorder of the system

Gibbs free energy change (G) thermodynamic property defined in terms of system enthalpy and entropy; all spontaneous processes involve a decrease in G

microstate possible configuration or arrangement of matter and energy within a system

nonspontaneous process process that requires continual input of energy from an external source

reversible process process that takes place so slowly as to be capable of reversing direction in response to an infinitesimally small change in conditions; hypothetical construct that can only be approximated by real processes

second law of thermodynamics all spontaneous processes involve an increase in the entropy of the universe

spontaneous change process that takes place without a continuous input of energy from an external source

standard entropy (S°) entropy for one mole of a substance at 1 bar pressure; tabulated values are usually determined at 298.15 K

standard entropy change (ΔS°) change in entropy for a reaction calculated using the standard entropies

standard free energy change (ΔG°) change in free energy for a process occurring under standard conditions (1 bar pressure for gases, 1 M concentration for solutions)

standard free energy of formation (ΔG°f) change in free energy accompanying the formation of one mole of substance from its elements in their standard states

third law of thermodynamics entropy of a perfect crystal at absolute zero (0 K) is zero

Key Equations

- ΔS = [latex]\frac {q_{\text{rev}}}{\text{T}}[/latex]

- S = k ln W

- ΔS = k ln [latex]\frac{\text{W}_{f}}{\text{W}_{i}}[/latex]

- ΔS° = ∑vS°(products) - ∑vS°(reactants)

- ΔS = [latex]\frac{q_{\text{rev}}}{\text{T}}[/latex]

- ΔSuniv = ΔSsys + ΔSsurr

- ΔSuniv = ΔSsys + ΔSsurr = ΔSsys + [latex]\frac{q_{\text{surr}}}{\text{T}}[/latex]

- ΔG = ΔH - TΔS

- ΔG = ΔG° + RT ln Q

- ΔG° = -RT ln K

Summary

Spontaneity

Chemical and physical processes have a natural tendency to occur in one direction under certain conditions. A spontaneous process occurs without the need for a continual input of energy from some external source, while a nonspontaneous process requires such. Systems undergoing a spontaneous process may or may not experience a gain or loss of energy, but they will experience a change in the way matter and/or energy is distributed within the system.

Entropy

Entropy (S) is a state function that can be related to the number of microstates for a system (the number of ways the system can be arranged) and to the ratio of reversible heat to kelvin temperature. It may be interpreted as a measure of the dispersal or distribution of matter and/or energy in a system, and it is often described as representing the “disorder” of the system.

For a given substance, entropy depends on phase with Ssolid < Sliquid < Sgas. For different substances in the same physical state at a given temperature, entropy is typically greater for heavier atoms or more complex molecules. Entropy increases when a system is heated and when solutions form. Using these guidelines, the sign of entropy changes for some chemical reactions and physical changes may be reliably predicted.

The Second and Third Laws of Thermodynamics

The second law of thermodynamics states that a spontaneous process increases the entropy of the universe, Suniv > 0. If ΔSuniv < 0, the process is nonspontaneous, and if ΔSuniv = 0, the system is at equilibrium. The third law of thermodynamics establishes the zero for entropy as that of a perfect, pure crystalline solid at 0 K. With only one possible microstate, the entropy is zero. We may compute the standard entropy change for a process by using standard entropy values for the reactants and products involved in the process.

Free Energy

Gibbs free energy (G) is a state function defined with regard to system quantities only and may be used to predict the spontaneity of a process. A negative value for ΔG indicates a spontaneous process; a positive ΔG indicates a nonspontaneous process; and a ΔG of zero indicates that the system is at equilibrium. A number of approaches to the computation of free energy changes are possible.

Spontaneity

- What is a spontaneous reaction?

- What is a nonspontaneous reaction?

- Indicate whether the following processes are spontaneous or nonspontaneous.

- Liquid water freezing at a temperature below its freezing point

- Liquid water freezing at a temperature above its freezing point

- The combustion of gasoline

- A ball thrown into the air

- A raindrop falling to the ground

- Iron rusting in a moist atmosphere

- A helium-filled balloon spontaneously deflates overnight as He atoms diffuse through the wall of the balloon. Describe the redistribution of matter and/or energy that accompanies this process.

- Many plastic materials are organic polymers that contain carbon and hydrogen. The oxidation of these plastics in air to form carbon dioxide and water is a spontaneous process; however, plastic materials tend to persist in the environment. Explain.

Entropy

-

- In Figure 16.8 all possible distributions and microstates are shown for four different particles shared between two boxes. Determine the entropy change, ΔS, if the particles are initially evenly distributed between the two boxes, but upon redistribution all end up in Box (b).

- In Figure 16.8 all of the possible distributions and microstates are shown for four different particles shared between two boxes. Determine the entropy change, ΔS, for the system when it is converted from distribution (b) to distribution (d).

- How does the process described in the previous item relate to the system shown in Figure 16.4?

- Consider a system similar to the one in Figure 16.8, except that it contains six particles instead of four. What is the probability of having all the particles in only one of the two boxes in the case? Compare this with the similar probability for the system of four particles that we have derived to be equal to 1. What does this comparison tell us about even larger systems?

- Consider the system shown in Figure 16.9. What is the change in entropy for the process where the energy is initially associated only with particle A, but in the final state the energy is distributed between two different particles?

- Consider the system shown in Figure 16.9. What is the change in entropy for the process where the energy is initially associated with particles A and B, and the energy is distributed between two particles in different boxes (one in A-B, the other in C-D)?

- Arrange the following sets of systems in order of increasing entropy. Assume one mole of each substance and the same temperature for each member of a set.

- H2(g), HBrO4(g), HBr(g)

- H2O(l), H2O(g), H2O(s)

- He(g), Cl2(g), P4(g)

- At room temperature, the entropy of the halogens increases from I2 to Br2 to Cl2. Explain.

- Consider two processes: sublimation of I2(s) and melting of I2(s) (Note: the latter process can occur at the same temperature but somewhat higher pressure).

I2(s) ⟶ I2(g)

I2(s) ⟶ I2(l)

Is ΔS positive or negative in these processes? In which of the processes will the magnitude of the entropy change be greater?

- Indicate which substance in the given pairs has the higher entropy value. Explain your choices.

- C2H5OH(l) or C3H7OH(l)

- C2H5OH(l) or C2H5OH(g)

- 2H(g) or H(g)

- Predict the sign of the entropy change for the following processes.

- An ice cube is warmed to near its melting point.

- Exhaled breath forms fog on a cold morning.

- Snow melts.

- Predict the sign of the entropy change for the following processes. Give a reason for your prediction.

- Pb2+(aq) + S2−(aq) ⟶ PbS(s)

- 2Fe(s) + [latex]\frac{3}{2}[/latex]O2(g) ⟶ Fe2O2(s)

- 2C6H14(l) + 19O2(g) ⟶ 14H2O(g) + 12CO2(g)

- Write the balanced chemical equation for the combustion of methane, CH4(g), to give carbon dioxide and water vapor. Explain why it is difficult to predict whether ΔS is positive or negative for this chemical reaction.

- Write the balanced chemical equation for the combustion of benzene, C6H6(l), to give carbon dioxide and water vapor. Would you expect ΔS to be positive or negative in this process?

The Second and Third Laws of Thermodynamics

- What is the difference between ΔS and ΔS° for a chemical change?

- Calculate ΔS° for the following changes.

- SnCl4(l) ⟶ SnCl4(g)

- CS2(g) ⟶ CS2(l)

- Cu(s) ⟶ Cu(g)

- H2O(l) ⟶ H2O(g)

- 2H2(g) + O2(g) ⟶ 2H2O(l)

- 2HCl(g) + Pb(s) ⟶ PbCl2(s) + H2(g)

- Zn(s) + CuSO4(s) ⟶ Cu(s) + ZnSO4(s)

- Determine the entropy change for the combustion of liquid ethanol, C2H5OH, under the standard conditions to give gaseous carbon dioxide and liquid water.

- Determine the entropy change for the combustion of gaseous propane, C3H8, under the standard conditions to give gaseous carbon dioxide and water.

- “Thermite” reactions have been used for welding metal parts such as railway rails and in metal refining. One such thermite reaction is Fe2O3(s) + 2Al(s) ⟶ Al2O3(s) + 2Fe(s). Is the reaction spontaneous at room temperature under standard conditions? During the reaction, the surroundings absorb 851.8 kJ/mol of heat.

- Using the relevant S° values listed in Appendix G, calculate ΔS° for the following changes:

- N2(g) + 3H2(g) ⟶ 2NH3(g)

- N2(g) + 5O2(g) ⟶ N2O5(g)

- From the following information, determine ΔS° for the following:

N(g) + O(g) ⟶ NO(g)ΔS° = ?

N2(g) + O2(g) ⟶ 2NO(g)ΔS° = 24.8 J/K

N2(g) ⟶2N(g)ΔS° = 115.0 J/K

O2(g) ⟶ 2O(g)ΔS° = 117.0 J/K - By calculating ΔSuniv at each temperature, determine if the melting of 1 mole of NaCl(s) is spontaneous at 500°C and at 700 °C.

S°NaCl(s) = 72.11 [latex]\frac{\text{J}}{\text{mol · K}}[/latex]

S°NaCl(s) = 95.06 [latex]\frac{\text{J}}{\text{mol · K}}[/latex]

H°fusion= 27.95 kJ/mol

What assumptions are made about the thermodynamic information (entropy and enthalpy values) used to solve this problem? - Use the standard entropy data in Appendix G to determine the change in entropy for each of the following reactions. All the processes occur at the standard conditions and 25 °C.

- MnO2(s) ⟶ Mn(s) + O2(g)

- H2(g) + Br2(l) ⟶ 2HBr(g)

- Cu(s) + S(g) ⟶ CuS(s)

- 2LiOH(s) + CO2(g) ⟶ Li2CO3(s) + H2O(g)

- CH4(g) + O2(g) ⟶ C(s, graphite) + 2H2O(g)

- CS2(g) + 3Cl2(g) ⟶ CCl4(g) + S2Cl2(g)

- Use the standard entropy data in Appendix G to determine the change in entropy for each of the reactions listed in Exercise 16.28. All the processes occur at the standard conditions and 25 °C.

Free Energy

-

- What is the difference between ΔG and ΔG° for a chemical change?

- A reaction has ΔH° = 100 kJ/mol and ΔS° = 250 J/mol·K. Is the reaction spontaneous at room temperature? If not, under what temperature conditions will it become spontaneous?

- Explain what happens as a reaction starts with ΔG < 0 (negative) and reaches the point where ΔG = 0.

- Use the standard free energy of formation data in Appendix G to determine the free energy change for each of the following reactions, which are run under standard state conditions and 25 °C. Identify each as either spontaneous or nonspontaneous at these conditions.

- MnO2(s) ⟶ Mn(s) + O2(g)

- H2(g) + Br2(l) ⟶ 2HBr(g)

- Cu(s) + S(g) ⟶ CuS(s)

- 2LiOH(s) + CO2(g) ⟶ Li2CO3(s) + H2O(g)

- CH4(g) + O2(g) ⟶ C(s, graphite) + 2H2O(g)

- CS2(g) + 3Cl2(g) ⟶ CCl4(g) + S2Cl2(g)

- Use the standard free energy data in Appendix G to determine the free energy change for each of the following reactions, which are run under standard state conditions and 25 °C. Identify each as either spontaneous or nonspontaneous at these conditions.

- C(s, graphite) + O2(g) ⟶ CO2(g)

- O2(g) + N2(g) ⟶ 2NO(g)

- 2Cu(s) + S(g) ⟶ Cu2S(s)

- CaO(s) + H2O(l) ⟶ Ca(OH)2(s)

- Fe2O3(s) + 3CO(g) ⟶ 2Fe(s) + 3CO2(g)

- CaSO4 ·2H2O(s) ⟶ CaSO4(s) + 2H2O(g)

- Given:P4(s) + 5O2(g) ⟶ P4O10(s) ΔG° = −2697.0 kJ/mol

2H2(g) + O2(g) ⟶ 2H2O(g) ΔG° = −457.18 kJ/mol

6H2O(g) + P4O10(s) ⟶ 4H3PO4(l) ΔG° = −428.66 kJ/mol- Determine the standard free energy of formation, ΔG°f

- How does your calculated result compare to the value in Appendix G? Explain.

- Is the formation of ozone (O3(g)) from oxygen (O2(g)) spontaneous at room temperature under standard state conditions?

- Consider the decomposition of red mercury(II) oxide under standard state conditions.2HgO(s, red) ⟶ 2Hg(l) + O2(g)

- Is the decomposition spontaneous under standard state conditions?

- Above what temperature does the reaction become spontaneous?

- Among other things, an ideal fuel for the control thrusters of a space vehicle should decompose in a spontaneous exothermic reaction when exposed to the appropriate catalyst. Evaluate the following substances under standard state conditions as suitable candidates for fuels.

- Ammonia: 2NH3(g) ⟶ N2(g) + 3H2(g)

- Diborane: B2H6(g) ⟶ 2B(g) + 3H2(g)

- Hydrazine: N2H4(g) ⟶ N2(g) + 2H2(g)

- Hydrogen peroxide: H2O2(l) ⟶ H2O(g) + 1O2(g)

- Calculate ΔG° for each of the following reactions from the equilibrium constant at the temperature given.

- N2(g) + O2(g) ⟶ 2NO(g) T = 2000 °C Kp = 4.1 × 10−4

- H2(g) + I2(g) ⟶ 2HI(g) T = 400 °C Kp = 50.0

- CO2(g) + H2(g) ⟶ CO(g) + H2O(g) T = 980 °C Kp = 1.67

- CaCO3(s) ⟶ CaO(s) + CO2(g) T = 900 °C Kp = 1.04

- HF(aq) + H2O(l) ⟶ H3O+(aq) + F−(aq) T = 25 °C Kp = 7.2 × 10−4

- AgBr(s) ⟶ Ag+(aq) + Br−(aq)T = 25 °C Kp = 3.3 × 10−13

- Calculate ΔG° for each of the following reactions from the equilibrium constant at the temperature given.

- Cl2(g) + Br2(g) ⟶ 2BrCl(g) T = 25 °C Kp = 4.7 × 10−2

- 2SO2(g) + O2(g) ⇌ 2SO3(g) T = 500 °C Kp = 48.2

- H2O(l) ⇌ H2O(g) T = 60 °C Kp = 0.196 atm

- CoO(s) + CO(g) ⇌ Co(s) + CO2(g) T = 550 °C Kp = 4.90 × 102

- CH3NH2(aq) + H2O(l) ⟶ CH3NH3 +(aq) + OH−(aq) T = 25 °C Kp = 4.4 × 10−4

- PbI2(s) ⟶ Pb2+(aq) + 2I−(aq) T = 25 °C Kp = 8.7 × 10−9

- Calculate the equilibrium constant at 25 °C for each of the following reactions from the value of ΔG° given.

- O2(g) + 2F2(g) ⟶ 2OF2(g) ΔG° = −9.2 kJ

- I2(s) + Br2(l) ⟶ 2IBr(g) ΔG° = 7.3 kJ

- 2LiOH(s) + CO2(g) ⟶ Li2CO3(s) + H2O(g) ΔG° = −79 kJ

- N2O3(g) ⟶ NO(g) + NO2(g) ΔG° = −1.6 kJ

- SnCl4(l) ⟶ SnCl4(l) ΔG° = 8.0 kJ

- Calculate the equilibrium constant at 25 °C for each of the following reactions from the value of ΔG° given.

- I2(s) + Cl2(g) ⟶ 2ICl(g) ΔG° = −10.88 kJ

- H2(g) + I2(s) ⟶ 2HI(g) ΔG° = 3.4 kJ

- CS2(g) + 3Cl2(g) ⟶ CCl4(g) + S2Cl2(g) ΔG° = −39 kJ

- 2SO2(g) + O2(g) ⟶ 2SO3(g) ΔG° = −141.82 kJ

- CS2(g) ⟶ CS2(l) ΔG° = −1.88 kJ

- Calculate the equilibrium constant at the temperature given.

- O2(g) + 2F2(g) ⟶ 2F2O(g) (T = 100 °C)

- I2(s) + Br2(l) ⟶ 2IBr(g) (T = 0.0 °C)

- 2LiOH(s) + CO2(g) ⟶ Li2CO3(s) + H2O(g) (T = 575 °C)

- (d) N2O3(g) ⟶ NO(g) + NO2(g) (T = −10.0 °C)

- SnCl4(l) ⟶ SnCl4(g) (T = 200 °C)

- Calculate the equilibrium constant at the temperature given.

- I2(s) + Cl2(g) ⟶ 2ICl(g) (T = 100 °C)

- H2(g) + I2(s) ⟶ 2HI(g) (T = 0.0 °C)

- CS2(g) + 3Cl2(g) ⟶ CCl4(g) + S2Cl2(g) (T = 125 °C)

- 2SO2(g) + O2(g) ⟶ 2SO3(g) (T = 675 °C)

- CS2(g) ⟶ CS2(l) (T = 90 °C)

- Consider the following reaction at 298 K:

N2O4(g) ⇌ 2NO2(g) KP = 0.142

What is the standard free energy change at this temperature? Describe what happens to the initial system, where the reactants and products are in standard states, as it approaches equilibrium.

- Determine the normal boiling point (in kelvin) of dichloroethane, CH2Cl2. Find the actual boiling point using the Internet or some other source, and calculate the percent error in the temperature. Explain the differences, if any, between the two values.

- Under what conditions is N2O3(g) ⟶ NO(g) + NO2(g) spontaneous?

- At room temperature, the equilibrium constant (Kw) for the self-ionization of water is 1.00 × 10−14. Using this information, calculate the standard free energy change for the aqueous reaction of hydrogen ion with hydroxide ion to produce water. (Hint: The reaction is the reverse of the self-ionization reaction.)

- Hydrogen sulfide is a pollutant found in natural gas. Following its removal, it is converted to sulfur by the reaction 2H2 S(g) + SO2(g) ⇌ [latex]\frac{3}{8}[/latex] S8(s, rhombic) + 2H2O(l). What is the equilibrium constant for this reaction? Is the reaction endothermic or exothermic?

- Consider the decomposition of CaCO3(s) into CaO(s) and CO2(g). What is the equilibrium partial pressure of CO2 at room temperature?

- In the laboratory, hydrogen chloride (HCl(g)) and ammonia (NH3(g)) often escape from bottles of their solutions and react to form the ammonium chloride (NH4Cl(s)), the white glaze often seen on glassware. Assuming that the number of moles of each gas that escapes into the room is the same, what is the maximum partial pressure of HCl and NH3 in the laboratory at room temperature? (Hint: The partial pressures will be equal and are at their maximum value when at equilibrium.)

- Benzene can be prepared from acetylene. 3C2H2(g) ⇌ C6H6(g). Determine the equilibrium constant at 25°C and at 850 °C. Is the reaction spontaneous at either of these temperatures? Why is all acetylene not found as benzene?

- Carbon dioxide decomposes into CO and O2 at elevated temperatures. What is the equilibrium partial pressure of oxygen in a sample at 1000 °C for which the initial pressure of CO2 was 1.15 atm?

- Carbon tetrachloride, an important industrial solvent, is prepared by the chlorination of methane at 850 K.

CH4(g) + 4Cl2(g) ⟶ CCl4(g) + 4HCl(g)What is the equilibrium constant for the reaction at 850 K? Would the reaction vessel need to be heated or cooled to keep the temperature of the reaction constant?

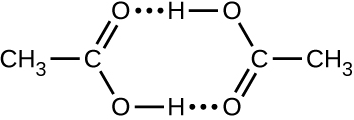

- Acetic acid, CH3CO2H, can form a dimer, (CH3CO2H)2, in the gas phase.

2CH3CO2 H(g) ⟶ (CH3CO2 H)2(g)

The dimer is held together by two hydrogen bonds with a total strength of 66.5 kJ per mole of dimer.

At 25 °C, the equilibrium constant for the dimerization is 1.3 × 103 (pressure in atm). What is ΔS° for the reaction?

- Determine ΔGº for the following reactions.

- Antimony pentachloride decomposes at 448 °C. The reaction is:

SbCl5(g) ⟶SbCl3(g) + Cl2(g)

An equilibrium mixture in a 5.00 L flask at 448 °C contains 3.85 g of SbCl5, 9.14 g of SbCl3, and 2.84 g of Cl2.

- Chlorine molecules dissociate according to this reaction:

Cl2(g) ⟶ 2Cl(g)

1.00% of Cl2 molecules dissociate at 975 K and a pressure of 1.00 atm.

- Antimony pentachloride decomposes at 448 °C. The reaction is:

- Given that the ΔG°f for Pb2+(aq) and Cl−(aq) is −24.3 kJ/mole and −131.2 kJ/mole respectively, determine the solubility product, Ksp, for PbCl2(s).

- Determine the standard free energy change, ΔG°f , for the formation of S2−(aq) given that the ΔG°f for Ag+(aq) and Ag2S(s) are 77.1 kJ/mole and −39.5 kJ/mole respectively, and the solubility product for Ag2S(s) is 8 × 10−51.

- Determine the standard enthalpy change, entropy change, and free energy change for the conversion of diamond to graphite. Discuss the spontaneity of the conversion with respect to the enthalpy and entropy changes. Explain why diamond spontaneously changing into graphite is not observed.

- The evaporation of one mole of water at 298 K has a standard free energy change of 8.58 kJ.

H2O(l) ⇌ H2O(g) ΔG° = 8.58 kJ- Is the evaporation of water under standard thermodynamic conditions spontaneous?

- Determine the equilibrium constant, KP, for this physical process.

- By calculating ∆G, determine if the evaporation of water at 298 K is spontaneous when the partial pressure of water, PH2O, is 0.011 atm.

- If the evaporation of water were always nonspontaneous at room temperature, wet laundry would never dry when placed outside. In order for laundry to dry, what must be the value of PH2 O in the air?

- In glycolysis, the reaction of glucose (Glu) to form glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) requires ATP to be present as described by the following equation:

Glu + ATP ⟶ G6P + ADP ΔG° = −17 kJ

In this process, ATP becomes ADP summarized by the following equation:

ATP ⟶ ADP ΔG° = −30 kJ

Determine the standard free energy change for the following reaction, and explain why ATP is necessary to drive this process:

Glu ⟶ G6P ΔG° = ?

- One of the important reactions in the biochemical pathway glycolysis is the reaction of glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) to form fructose-6-phosphate (F6P):

G6P ⇌ F6P ΔG° = 1.7 kJ

- Is the reaction spontaneous or nonspontaneous under standard thermodynamic conditions?

- Standard thermodynamic conditions imply the concentrations of G6P and F6P to be 1 M, however, in a typical cell, they are not even close to these values. Calculate ΔG when the concentrations of G6P and F6P are 120 μM and 28 μM respectively, and discuss the spontaneity of the forward reaction under these conditions. Assume the temperature is 37 °C.

- Without doing a numerical calculation, determine which of the following will reduce the free energy change for the reaction, that is, make it less positive or more negative, when the temperature is increased. Explain.

- N2(g) + 3H2(g) ⟶ 2NH3(g)

- HCl(g) + NH3(g) ⟶ NH4Cl(s)

- (NH4)2 Cr2 O7(s) ⟶ Cr2 O3(s) + 4H2O(g) + N2(g)

- 2Fe(s) + 3O2(g) ⟶ Fe2 O3(s)

- When ammonium chloride is added to water and stirred, it dissolves spontaneously and the resulting solution feels cold. Without doing any calculations, deduce the signs of ΔG, ΔH, and ΔS for this process, and justify your choices.

- An important source of copper is from the copper ore, chalcocite, a form of copper(I) sulfide. When heated, the Cu2S decomposes to form copper and sulfur described by the following equation:

Cu2 S(s) ⟶ Cu(s) + S(s)

- Determine ΔG° for the decomposition of Cu2S(s).

- The reaction of sulfur with oxygen yields sulfur dioxide as the only product. Write an equation that describes this reaction, and determine ΔG° for the process.

- The production of copper from chalcocite is performed by roasting the Cu2S in air to produce the Cu. By combining the equations from Parts (a) and (b), write the equation that describes the roasting of the chalcocite, and explain why coupling these reactions together makes for a more efficient process for the production of the copper.

- What happens to ΔG (becomes more negative or more positive) for the following chemical reactions when the partial pressure of oxygen is increased?

- S(s) + O2(g) ⟶ SO2(g)

- 2SO2(g) + O2(g) ⟶ 2SO3(g)

- HgO(s) ⟶ Hg(l) + O2(g)