2.4 Mortgages Part I: Terminology

Renting Versus owning

Personal Finance. Provided by: Saylor Academy. Located at: https://saylordotorg.github.io/text_personal-finance. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

If you have already decided on a goal of home ownership, you have already compared the costs and benefits of the alternative, which is renting. Renting requires relatively few initial legal or financial commitments. The renter signs a lease that spells out the terms of the rental agreement: term, rent, terms of payments and fees, restrictions such as pets or smoking, and charges for damages. A renter is usually required to give the landlord a security deposit to cover the landlord’s costs of repairs or cleaning, as necessary, when the tenant moves out. If the deposit is not used, it is returned to the departing tenant (although without any interest earned).

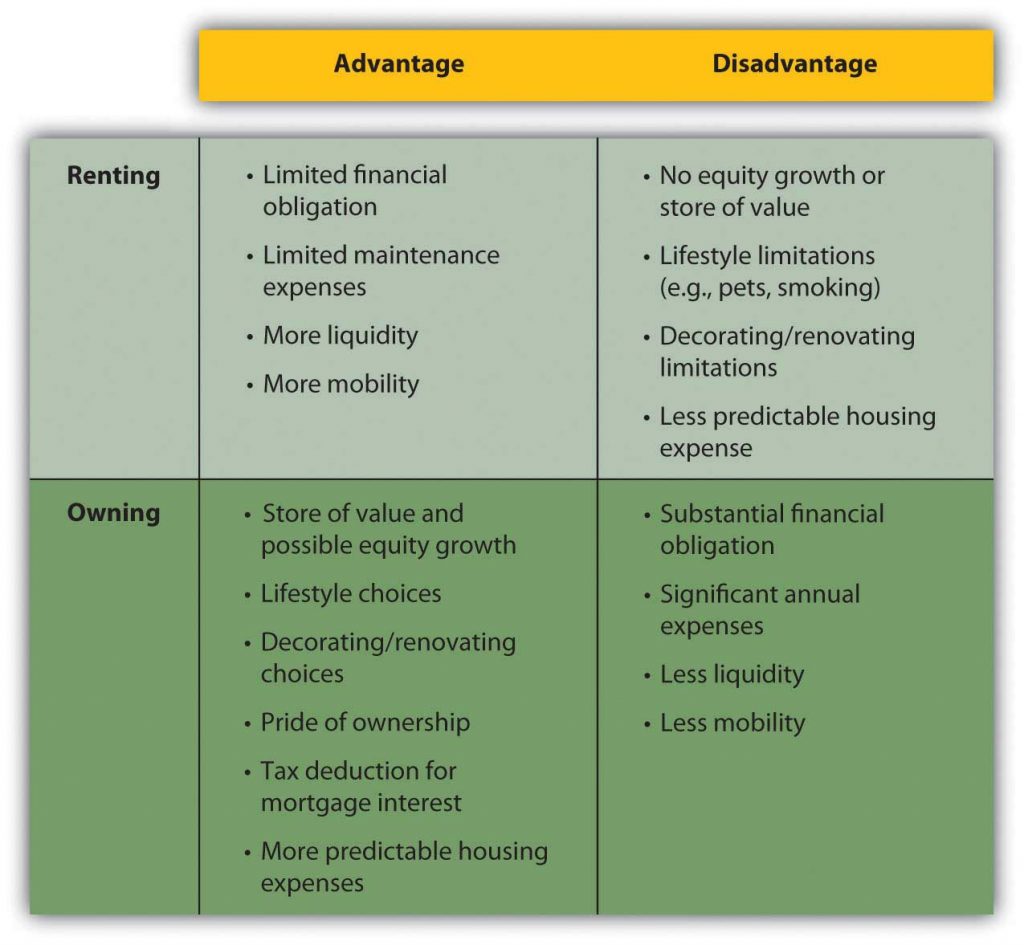

Some general advantages and disadvantages of renting and owning are shown in Figure 2.4.1 below.

The choice of whether to rent or to own follows the pattern of life stages. People rent early in their adult lives because they typically have fewer financial resources and put a higher value on mobility, usually to keep more career flexibility. Since incomes are usually low, the tax advantages of ownership don’t have much benefit.

As family size grows, the quality of life for dependents typically takes precedence, and a family looks for the added space and comfort of a home and its benefits as an investment. This is the mid-adult stage of accumulating assets and building wealth. As income rises, the tax benefit becomes more valuable, too.

Often, in retirement, with both incomes and family size smaller, older adults will downsize to an apartment, shedding responsibilities and financial commitments.

Home ownership decisions vary: some people just never want the responsibilities of ownership, while some just always want a place of their own.

Finding an apartment is much like finding a home in terms of assessing its attributes, comparing choices, and making a choice. Landlords, property managers, and agents all rent properties and use various media to advertise an available space. Since the rent for an apartment is a regular expense, financed from current income (not long-term debt), you need to find only the apartment and not the financing, which simplifies the process considerably.

Affordable housing

We will do calculations shortly, but before we do let us talk a bit about what affordable housing means.

Personal Finance. Provided by: Saylor Academy. Located at: https://saylordotorg.github.io/text_personal-finance. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

Before looking for a house that offers what you want, you need to identify a price range that you can afford. Most people use financing to purchase a home, so your ability to access financing or get a loan will determine the price range of the house you can buy. Since your home and your financing are long-term commitments, you need to be careful to try to include future changes in your thinking.

For example, Jill and Jack are both twenty-five years old, newly married, and looking to buy their first home. Both work and earn good incomes. The real estate market is strong, especially with mortgage rates relatively low. They buy a two-bedroom condo in a new development as a starter home.

Fast-forward five years. Jill is expecting their second child; while the couple is happy about the new baby, neither can imagine how they will all fit in their already cramped space. They would love to sell the condo and purchase a larger home with a yard for the kids, but the real estate market has slowed, mortgage rates have risen, and a plant closing last year has driven up unemployment in their area. Jill hasn’t worked outside the home since their first child was born two years ago—they are just getting by on one salary and a new baby will increase their expenses—making it even more difficult to think about financing a larger home.

A lender will look at your income, your current debts, and credit history to assess your ability to assume a mortgage. Your credit score is an important tool for the lender, who may also request verification of employment and income from your employer.

Lenders do their own calculations of how much debt you can afford, based on a reasonable percentage, usually about 33 percent, of your monthly gross income that should go toward your monthly housing costs, or principal, interest, taxes, and insurance (PITI). If you have other debts, your PITI plus your other debt repayments should be no more than about 38 percent of your gross income. Those percentages will be adjusted for income level, credit score, and amount of the down payment.

Say the lender assumes that 38 percent of your monthly gross income (annual gross income divided by twelve) should cover your PITI plus any other debt payments. Subtracting your other debt payments and estimated cost of taxes and insurance leaves you with a figure for affordable monthly mortgage payments. Dividing that figure by the mortgage factor for your mortgage’s maturity and mortgage rate shows the affordable mortgage overall. Knowing what percentage your mortgage will be of the home’s purchase price, you can calculate the maximum purchase price of the home that you can afford. That affordable home purchase price is based on your gross income, other debts, taxes, insurance, mortgage rate, mortgage maturity, and down payment.

These kinds of calculations give both you and your lender a much clearer idea of what you can afford. You may want to sit down with a potential lender and have this discussion before you do any serious house hunting, so that you have a price range in mind before you shop. Mortgage affordability calculators are also available online.

The search Process

Two Cents: How Do You Actually Buy a House? (all rights reserved)

After understanding exactly what you are looking for in a home and what you can afford, you can organize your efforts and begin your search.

Typically, buyers use a realtor and realty listings to identify homes for sale. A real estate broker can add value to your search by providing information about the house and property, the neighborhood and its schools, recreational and cultural opportunities, and costs of living.

Remember, however, that the broker or its agent, while helping you gather information and assess your choices, is working for the sellers and will be compensated by the seller when a sale is made. Consider paying for the services of a buyer’s agent, a fee-based real estate broker who works for the buyer to identify choices independently of the purchase. The real estate industry is regulated by state and federal laws as well as by self-regulatory bodies, and real estate agents must be licensed to operate.

Increasingly, sellers are marketing their homes directly to save the cost of using a broker. A real estate broker typically takes a negotiable amount up to 6 percent of the purchase price, from which it pays a commission to the real estate agent. “For sale by owner” sites on the Internet can make the exchange of housing information easier and more convenient for both buyers and sellers. For example, Web sites such as Picketfencepreview.com serve home sellers and buyers directly. Keep in mind, however, that sellers acting as their own brokers and agents are not licensed or regulated and may not be knowledgeable about federal and state laws governing real estate transactions, potentially increasing your risk.

After you narrow your search and choose a prospective home in your price range, you have the home inspected to assess its condition and project the cost of any repairs or renovations. Many states require a home inspection before signing a purchase agreement or as a condition of the agreement.

As with a car, it is best to hire a professional (a structural engineer, contractor, or licensed home inspector) to do the home inspection. For example, see the American Association of Home Inspectors at http://www.ashi.org/. A professional will be able to spot not only potential problems but also evidence of past problems that may have been fixed improperly or that may recur—for example, water in the basement or leaks in the roof. If there are problems, you will need an estimate for the cost of fixing them. If there are significant and immediate repair or renovation costs projected by the home’s condition, you may try to reduce the purchase price of the property by those costs. You don’t want any surprises after you buy the house, especially costly ones.

You will also want to do a title search, as required by your lender, to verify that there are no liens or claims outstanding against the property. For example, the previous owners may have had a dispute with a contractor and never paid his bill, and the contractor may have filed a lien or a claim against the property that must be resolved before the property can change hands. There are several other kinds of liens; for example, a tax lien is imposed to secure payment of overdue taxes.

Note: The next two videos are kind of boring and full of legal concepts, but are very important!

Khan Academy: Titles and Deeds in Real Estate (CC BY)

Khan Academy: Title Insurance (CC BY)

A lawyer or a title search company can do the search, which involves checking the municipal or town records where a lien would be filed. A title search will also reveal if previous owners have deeded any rights—such as development rights or water rights, for example, or grants of right-of-way across the property—that would diminish its value.

The Purchase process

Now that you’ve chosen your home and figured out the financing, all that’s left to do is sign the papers, right?

Once you have found a house, you will make an offer to the seller, who will then accept or reject your offer. If the offer is rejected, you may try to negotiate with the seller or you may decide to forgo this purchase. If your offer is accepted, you and the seller will sign a formal agreement called a purchase and sale agreement, specifying the terms of the sale. You will be required to pay a nonrefundable deposit, or earnest money, when the purchase and sale agreement is signed. That money will be held in escrow or in a restricted account and then applied toward the closing costs at settlement.

The purchase and sale agreement will include the following terms and conditions:

- A legal description of the property, including boundaries, with a site survey contingency

- The sale price and deposit amount

- A mortgage contingency, stating that the sale is contingent on the final approval of your financing

- The closing date and location, mutually agreed upon by buyer and seller

- Conveyances or any agreements made as part of the offer—for example, an agreement as to whether the kitchen appliances are sold with the house

- A home inspection contingency specifying the consequences of a home inspection and any problems that it may find, if not already completed and included in the price negotiation

- Possession date, usually the closing date

- A description of the property insurance policy that will cover the home until the closing date

Property disclosures of any problems with the property that must be legally disclosed, which vary by state, except that lead-paint disclosure is a federal mandate for any housing built before 1978.

After the purchase and sale agreement is signed, any conditions that it specified must be fulfilled before the closing date. If those conditions are the seller’s responsibility, you will want to be sure that they have been fulfilled before closing. Read all the documents before you sign them and get copies of everything you sign. Do not hesitate to ask questions. You will live with your mortgage, and your house, for a long time.

The costs of a mortgage

Personal Finance. Provided by: Saylor Academy. Located at: https://saylordotorg.github.io/text_personal-finance. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

Banks, credit unions, finance companies, and mortgage finance companies sell mortgages. They profit by lending and competing for borrowers. It makes sense to shop around for a mortgage, as rates and terms (i.e., the borrowers’ costs and conditions) may vary widely. The Internet has made it easy to compare; a quick search for “mortgage rates” yields many Web sites that provide national and state averages, lenders in your area, comparable rates and terms, and free mortgage calculators.

You may feel more comfortable getting your mortgage through your local bank, which may process the loan and then sell the mortgage to a larger financial institution. The local bank usually continues to service the loan, to collect the payments, but those cash flows are passed through to the financial institution (usually a much larger bank) that has bought the mortgage. This secondary mortgage market allows your local bank to have more liquidity and less risk, as it gets repaid right away, allowing it to make more loans. As long as you continue to make your payments, your only interaction is with the bank that is servicing the loan. Alternatively, local banks may earmark a percentage of mortgages to keep “in house” rather than sell.

The U.S. government assists some groups to obtain home loans, such as Native Americans, Americans with disabilities, and veterans. See, for example, http://www.homeloans.va.gov/ondemand_ vets_stream_video.htm.

Keep in mind that the costs discussed in this chapter, associated with various kinds of mortgages, may change. The real estate market, government housing policies, and government regulation of the mortgage financing market may change at any time. When it is time for you to shop for a mortgage, therefore, be sure you are informed of current developments.

Brian Kimball: How Does Escrow Work? (all rights reserved)

Types of Mortgages

Traditional Mortgage

The mortgage we will discuss in this class is just a traditional fixed-rate mortgage. As mentioned, failure to provide a 20% down payment will require the payment of private mortgage insurance. The bank may also set other requirements like the purchase of title insurance and homeowner’s insurance. Banks are governed by all applicable anti-discrimination and truth-in-lending laws and regulations.

VA Loan

From: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/VA_loan (CC BY)

A VA loan is a mortgage loan in the United States guaranteed by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). The program is for American veterans, military members currently serving in the U.S. military, reservists and select surviving spouses (provided they do not remarry) and can be used to purchase single-family homes, condominiums, multi-unit properties, manufactured homes and new construction. The VA does not originate loans, but sets the rules for who may qualify, issues minimum guidelines and requirements under which mortgages may be offered and financially guarantees loans that qualify under the program.

The basic intention of the VA home loan program is to supply home financing to eligible veterans and to help veterans purchase properties with no down payment. The loan may be issued by qualified lenders.

The VA loan allows veterans 103.3 percent financing without private mortgage insurance (PMI) or a 20 percent second mortgage and up to $6,000 for energy efficient improvements. A VA funding fee of 0 to 3.3% of the loan amount is paid to the VA; this fee may also be financed and some may qualify for an exemption. In a purchase, veterans may borrow up to 103.3% of the sales price or reasonable value of the home, whichever is less. Since there is no monthly PMI, more of the mortgage payment goes directly towards qualifying for the loan amount, allowing for larger loans with the same payment. In a refinance, where a new VA loan is created, veterans may borrow up to 100% of a property’s reasonable value, where allowed by state laws. In a refinance where the loan is a VA loan refinancing to VA loan (IRRRL Refinance), the veteran may borrow up to 100.5% of the total loan amount. The additional .5% is the funding fee for a VA Interest Rate Reduction Refinance.

FHA Loan

From: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FHA_insured_loan (CC BY)

An FHA insured loan is a US Federal Housing Administration mortgage insurance backed mortgage loan that is provided by an FHA-approved lender. FHA insured loans are a type of federal assistance. They have historically allowed lower-income Americans to borrow money to purchase a home that they would not otherwise be able to afford. Because this type of loan is more geared towards new house owners than real estate investors, FHA loans are different from conventional loans in the sense that the house must be owner-occupant for at least a year.[1] Since loans with lower down-payments usually involve more risk to the lender, the home-buyer must pay a two-part mortgage insurance that involves a one-time bulk payment and a monthly payment to compensate for the increased risk.[1]:15

The program originated during the Great Depression of the 1930s when the rates of foreclosures and defaults rose sharply, and the program was intended to provide lenders with sufficient insurance. The government subsidized some FHA programs, but the goal was to make it self-supporting based on borrowers’ insurance premiums. Over time, private mortgage insurance (PMI) companies came into play. Now FHA primarily serves people who cannot afford a conventional down payment or do not qualify for PMI. The program has since this time been modified to accommodate the heightened recession.

Down payment assistance and community redevelopment programs offer affordable housing opportunities to first-time homebuyers, low- and moderate-income individuals, and families who wish to achieve homeownership. Grant types include seller funded programs, the [1] Grant America Program and others, as well as programs that are funded by the federal government, such as the American Dream Down Payment Initiative. Many down payment grant programs are run by state and local governments, often using mortgage revenue bond funds.

The FHA employs a two-tiered mortgage insurance premium (MIP) schedule. To obtain mortgage insurance from the Federal Housing Administration, an upfront mortgage insurance premium (UFMIP) equal to 1.75% of the base loan amount at closing is required, and is normally financed into the total loan amount by the lender and paid to FHA on the borrower’s behalf. There is also a monthly mortgage insurance premium (MIP) which varies based on the amortization term and loan-to-value ratio.[27]

The monthly payment is not permanent, however, as there are several ways to get rid of the MIP. One way to remove the monthly payment is to establish at least a 20% equity on the FHA loan, which will allow the homeowner to apply for a refinance on their loan. Since the MIP is to ensure extra security against defaulting, if there are signs of financial instability, the refinance may be declined. However, the easiest and most guaranteed way to remove the MIP is to establish a 22% equity; after which, the mortgage insurance is automatically removed by the lender and is no longer required to be paid.[28][29]

Down Payment

Mortgages require a down payment, or a percentage of the purchase price paid in cash upon purchase. Most buyers use cash from savings, the proceeds of a house they are selling, or a family gift.

The size of the down payment does not affect the price of the house, but it can affect the cost of the financing. For a certain house price, the larger the down payment, the smaller the mortgage and, all things being equal, the lower the monthly payments.

We will explore the impact of different sized down payments once we run calculations.

Usually, if the down payment is less than 20 percent of the property’s sale price, the borrower has to pay for private mortgage insurance (PMI), which insures the lender against the costs of default. A larger down payment eliminates this expense for the borrower.

The down payment can offset the annual cost of the financing, but it creates opportunity cost and decreases your liquidity as you take money out of savings. Cash will also be needed for the closing costs or transaction costs of this purchase or for any immediate renovations or repairs. Those needs will have to be weighed against your available cash to determine the amount of your down payment.

Closing costs can run anywhere from 2-5% of the price of the home. Let us consider a case where you want to buy a $200,000 house with a 20% down payment and 4% closing costs. This means that you would need close to $50,000 in cash to purchase the house! If you are not able to come up with that much, there are other options available but, as mentioned earlier, do come with PMI.

Monthly Payment

The monthly payment is the ongoing cash flow obligation of the loan. If you don’t pay this payment, you are in default on the loan and may eventually lose the house with no compensation for the money you have already put into it. Your ability to make the monthly payment determines your ability to keep the house.

The interest rate and the maturity (lifetime of the mortgage) determine the monthly payment amount. With a fixed-rate mortgage, the interest rate remains the same over the entire maturity of the mortgage, and so does the monthly payment. Conventional mortgages are fixed-rate mortgages for thirty, twenty, or fifteen years.

The longer the maturity, the greater the interest rate, because the lender faces more risk the longer it takes for the loan to be repaid.

A fixed-rate mortgage is structured as an annuity: regular periodic payments of equal amounts. Some of the payment is repayment of the principal and some is for the interest expense. As you make a payment, your balance gets smaller, and so the interest portion of your next payment is smaller, and the principal payment is larger. In other words, as you continue making payments, you are paying off the balance of the loan faster and faster and paying less and less interest.

In the early years of the mortgage, your payments are mostly interest, while in the last years they are mostly principal. It is important to distinguish between them because the mortgage interest is tax deductible. That tax benefit is greater in the earlier years of the mortgage, when the interest expense is larger. We will take a look at amortization schedules shortly.

Points

Points are another kind of financing cost. One point is one percent of the mortgage. Points are paid to the lender as a form of prepaid interest when the mortgage originates and are used to decrease the mortgage rate. In other words, paying points is a way of buying a lower mortgage rate.

In deciding whether or not it is worth it to pay points, you need to think about the difference that the lower mortgage rate will make to your monthly payment and how long you will be paying this mortgage. How long will it take for the points to pay for themselves in reduced monthly payments? For example, suppose you have the following choices for a thirty-year, fixed rate, $200,000 mortgage: a mortgage rate of 6.5 percent with no points or a rate of 6 percent with 2 points. Paying the two points buys you a lower monthly payment and saves you $64 dollars per month. The two points cost $4,000 (2 percent of $200,000). At the rate of $64 per month, it will take 62.5 months ($4,000 ÷ 64) or a little over five years for those points to pay for themselves. If you do not plan on having this mortgage for that long, then paying the points is not worth it. Paying points has liquidity and opportunity costs up front that must be weighed against its benefit. Points are part of the closing costs, but borrowers do not have to pay them if they are willing to pay a higher interest rate instead.

Closing Costs

Other costs of a house purchase are transaction costs, that is, costs of making the transaction happen that are not direct costs of either the home or the financing. These are referred to as closing costs, as they are paid at the closing, the meeting between buyer and seller where the ownership and loan documents are signed and the property is actually transferred. The buyer pays these closing costs, including the appraisal fee, title insurance, and filing fee for the deed.

The lender will have required an independent appraisal of the home’s value to make sure that the amount of the mortgage is reasonable given the value of the house that secures it. The lender will also require a title search and contract for title insurance. The title company will research any claims or liens on the deed; the purchase cannot go forward if the deed may not be freely transferred. Over the term of the mortgage, the title insurance protects against flaws not found in the title and any claims that may result. The buyer also pays a fee to file the property deed with the township, municipality, or county. Some states may also have a property transfer tax that is the responsibility of the buyer.

Closings may take place in the office of the title company handling the transaction or at the registry of deeds. Closings also may take place in the lender’s offices, such as a bank, or an attorney’s office and usually are mediated between the buyer and the seller through their attorneys. Lawyers who specialize in real estate ensure that all legal requirements are met and all filings of legal documents are completed. For example, before signing, home buyers have a right to review a U.S. Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Settlement Statement twenty-four hours prior to the closing. This document, along with a truth-in-lending disclosure statement, sets out and explains all the terms of the transaction, all the costs of buying the house, and all closing costs. Both the buyer and the seller must sign the HUD document and are legally bound by it.

Property Taxes

From: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Property_tax (CC BY)

A property tax or millage rate[1] is an ad valorem tax on the value of a property, usually levied on real estate. The tax is levied by the governing authority of the jurisdiction in which the property is located. This can be a national government, a federated state, a county or geographical region or a municipality. Multiple jurisdictions may tax the same property.

It may be imposed annually or at the time of a real estate transaction, such as in real estate transfer tax. This tax can be contrasted to a rent tax, which is based on rental income or imputed rent, and a land value tax, which is a levy on the value of land, excluding the value of buildings and other improvements.

Under a property-tax system, the government requires or performs an appraisal of the monetary value of each property, and tax is assessed in proportion to that value.

The four broad types of property taxes are land, improvements to land (immovable man-made objects, such as buildings), personal property (movable man-made objects) and intangible property. Real property (also called real estate or realty) is the combination of land and improvements. We will focus on real property taxes in this class.

The property tax rate is typically given as a percentage. It may be expressed as a per mil (amount of tax per thousand currency units of property value), which is also known as a millage rate or mill (one-thousandth of a currency unit). To calculate the property tax, the authority multiplies the assessed value by the mill rate and then divides by 1,000. For example, a property with an assessed value of $50,000 located in a municipality with a mill rate of 20 mills would have a property tax bill of $1,000 per year.[5]

Homeowner’s Insurance

From: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Property_insurance (CC BY)

Property insurance provides protection against most risks to property, such as fire, theft and some weather damage. This includes specialized forms of insurance such as fire insurance, flood insurance, earthquake insurance, home insurance, or boiler insurance. Property is insured in two main ways—open perils and named perils.

Open perils cover all the causes of loss not specifically excluded in the policy. Common exclusions on open peril policies include damage resulting from earthquakes, floods, nuclear incidents, acts of terrorism, and war. Named perils require the actual cause of loss to be listed in the policy for insurance to be provided. The more common named perils include such damage-causing events as fire, lightning, explosion, and theft.

There are three types of insurance coverage. Replacement cost coverage pays the cost of repairing or replacing the property with like kind & quality regardless of depreciation or appreciation. Premiums for this type of coverage are based on replacement cost values, and not based on actual cash value. [5] Actual cash value coverage provides for replacement cost minus depreciation. Extended replacement cost will pay over the coverage limit if the costs for construction have increased. This generally will not exceed 25% of the limit. When obtaining an insurance policy, the limit is the maximum amount of benefit the insurance company will pay for a given situation or occurrence. Limits also include the ages below or above what an insurance company will not issue a new policy or continue a policy.[6]

This amount will need to fluctuate if the cost to replace homes in a neighborhood is rising; the amount needs to be in step with the actual reconstruction value of the home. In case of a fire, household content replacement is tabulated as a percentage of the value of the home. In case of high-value items, the insurance company may ask to specifically cover these items separate from the other household contents. One last coverage option is to have alternative living arrangements included in a policy. If property damage caused by a covered loss prevents a person from living in their home, policies can pay the expenses of alternate living arrangements (e.g., hotels and restaurant costs) for a specified period of time to compensate for the “loss of use” of the home until the owners can return. The additional living expenses limit can vary, but is typically set at up to 20% of the dwelling coverage limit. Owners need to talk with their insurance company for advice about appropriate coverage and determine what type of limit may be appropriate.[7]

Banks generally require insurance on the structure since they are part owners. This is generally included in your monthly bill which we will talk about later.

Adjustable Rate Mortgages

I will not discuss adjustable rate mortgages in this class other than to give information in this section. If you plan on remaining in a house, these are rarely a good idea. Think of these like the “low-low introductory offer” where you pay only $1 per month for a gym membership…but then realize you are also locked into $49.99/month for a year once the trial ends.

So far, the discussion has focused on fixed-rate mortgages, that is, mortgages with fixed or constant interest rates, and therefore payments, until maturity. With an adjustable-rate mortgage (ARM), the interest rate—and the monthly payment—can change. If interest rates rise, the monthly payment will increase, and if they fall, it will decrease. By federal law, increases in ARM interest rates cannot rise more than 2 percent at a time, but even with this rate cap, homeowners with ARMs are at risk of seeing their monthly payment increase. Borrowers can limit this interest rate risk with a payment cap, which, however, introduces another risk.

A payment cap limits the amount by which the payment can increase or decrease. That sounds like it would protect the borrower, but if the payment is capped and the interest rate rises, more of the payment pays for the interest expense and less for the principal payment, so the balance is paid down more slowly. If interest rates are high enough, the payment may be too small to pay all the interest expense, and any interest not paid will add to the principal balance of the mortgage.

In other words, instead of paying off the mortgage, your payments may actually increase your debt, and you could end up owing more money than you borrowed, even though you make all your required payments on time. This is called negative amortization. You should make sure you know if your ARM mortgage is this type of loan. You can voluntarily increase your monthly payment amount to avoid the negative effects of a payment cap.

Adjustable-rate mortgages are risky for borrowers. ARMs are usually offered at lower rates than fixed-rate mortgages, however, and may be more affordable. Borrowers who expect an increase in their disposable incomes, which would offset the risk of a higher payment, or who expect a decrease in interest rates, may prefer an adjustable-rate mortgage, which can have a maturity of up to forty years. Otherwise, a fixed-rate mortgage is better.

There are mortgages that combine fixed and variable rates—for example, offering a fixed rate for a specified period of time, and then an adjustable rate. Another type of mortgage is a balloon mortgage that offers fixed monthly payments for a specified period, usually three, five, or seven years, and then a final, large repayment of the principal. There are option ARMs, where you pay either interest only or principal only for the first few years of the loan, which makes it more affordable. While you are paying interest only, however, you are not accumulating equity in your investment.

We will only concern ourselves with traditional fixed-rate mortgages in this class.

Bank of America: Fixed versus Adjustable Rate Mortgages (all rights reserved)

https://youtu.be/rJgNbVTYgwM