3.5 Investment Topics

Personal Finance. Provided by: Saylor Academy. Located at: https://saylordotorg.github.io/text_personal-finance. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

Economic forces and financial behavior can converge to create extreme markets or financial crises, such as booms, bubbles, panics, crashes, or meltdowns. These atypical events actually happen fairly frequently. Between 1618 and 1998, there were thirty-eight financial crises globally, or one every ten years.Charles P. Kindleberger and Robert Aliber, Manias, Panics, and Crashes, 5th ed. (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2005). As an investor, you can expect to weather as many as six crises in your lifetime.

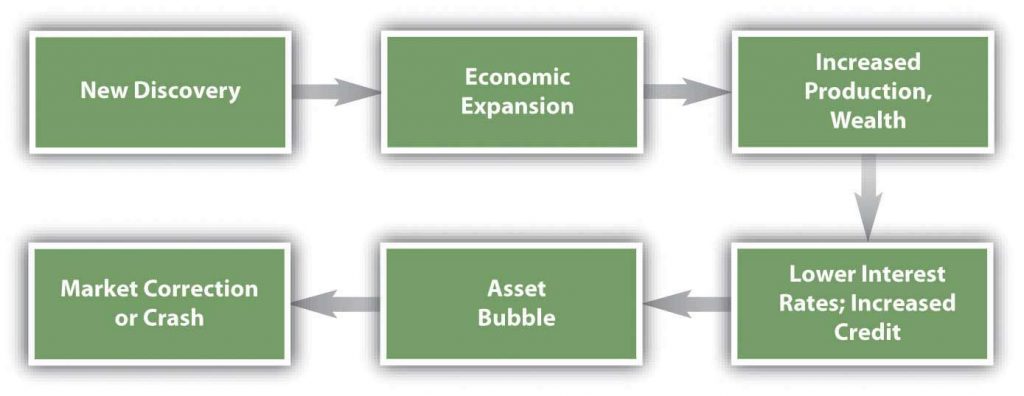

Patterns of events that seem to precipitate and follow the crises are shown in Figure 3.5.1. First a period of economic expansion is sparked by a new technology, the discovery of a new resource, or a change in political balances. This leads to increased production, markets, wealth, consumption, and investment, as well as increased credit and lower interest rates. People are looking for ways to invest their newfound wealth. This leads to an asset bubble, a rapid increase in the price of some asset: bonds, stocks, real estate, or commodities such as cotton, gold, oil, or tulip bulbs that seems to be positioned to prosper from this particular expansion.

The bubble continues, reinforced by the behavioral and market consequences that it sparks until some event pricks the bubble. Then asset values quickly deflate, and credit defaults rise, damaging the banking system. Having lost wealth and access to credit, people rein in their demand for consumption and investment, further slowing the economy.

n many cases, the event that started the asset speculation was not a macroeconomic event but nevertheless had consequences to the economy: the end of a war, a change of government, a change in policy, or a new technology. Often the asset that was the object of speculation was a resource for or an application of a new technology or an expansion into new territory that may have been critical to a new emphasis in the economy. In other words, the assets that became the objects of bubbles tended to be the drivers of a “new economy” at the time and thus were rationalized as investments rather than as speculation.

Many irrational financial behaviors—overconfidence, anchoring, availability bias, representativeness—are in play, until finally the market was shocked into reversal by a specific event or simply sank under its own weight.

Economists may argue that this is what you should expect, that markets expand and contract cyclically as a matter of course. In this view, a crash is nothing more than the correction for a bubble—market efficiency at work.

Ponzi Schemes

From: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ponzi_scheme (CC BY)

A Ponzi scheme (/ˈpɒnzi/, Italian: [ˈpontsi]; also a Ponzi game)[1] is a form of fraud that lures investors and pays profits to earlier investors with funds from more recent investors.[2] The scheme leads victims to believe that profits are coming from product sales or other means, and they remain unaware that other investors are the source of funds. A Ponzi scheme can maintain the illusion of a sustainable business as long as new investors contribute new funds, and as long as most of the investors do not demand full repayment and still believe in the non-existent assets they are purported to own.

Among the first recorded incidents to meet the modern definition of Ponzi scheme were carried out from 1869 to 1872 by Adele Spitzeder in Germany and by Sarah Howe in the United States in the 1880s through the “Ladies’ Deposit”. Howe offered a solely female clientele an 8% monthly interest rate, and then stole the money that the women had invested. She was eventually discovered and served three years in prison.[3] The Ponzi scheme was also previously described in novels; Charles Dickens‘ 1844 novel Martin Chuzzlewit and his 1857 novel Little Dorrit both feature such a scheme.[4]

In the 1920s, Charles Ponzi carried out this scheme and became well known throughout the United States because of the huge amount of money that he took in.[5] His original scheme was based on the legitimate arbitrage of international reply coupons for postage stamps, but he soon began diverting new investors’ money to make payments to earlier investors and to himself.[6] Unlike earlier, similar schemes, Ponzi’s gained considerable press coverage both within the United States and internationally both while it was being perpetrated and after it collapsed – this notoriety eventually led to the type of scheme being named after him.[7]

Characteristics

Typically, Ponzi schemes require an initial investment and promise above-average returns.[8] They use vague verbal guises such as “hedge futures trading“, “high-yield investment programs“, or “offshore investment” to describe their income strategy. It is common for the operator to take advantage of a lack of investor knowledge or competence, or sometimes claim to use a proprietary, secret investment strategy to avoid giving information about the scheme.

The basic premise of a Ponzi scheme is “to rob Peter to pay Paul“. Initially, the operator pays high returns to attract investors and entice current investors to invest more money. When other investors begin to participate, a cascade effect begins. The schemer pays a “return” to initial investors from the investments of new participants, rather than from genuine profits.

Often, high returns encourage investors to leave their money in the scheme, so that the operator does not actually have to pay very much to investors. The operator simply sends statements showing how much they have earned, which maintains the deception that the scheme is an investment with high returns. Investors within a Ponzi scheme may even face difficulties when trying to get their money out of the investment.

Operators also try to minimize withdrawals by offering new plans to investors where money cannot be withdrawn for a certain period of time in exchange for higher returns. The operator sees new cash flows as investors cannot transfer money. If a few investors do wish to withdraw their money in accordance with the terms allowed, their requests are usually promptly processed, which gives the illusion to all other investors that the fund is solvent and financially sound.

Ponzi schemes sometimes begin as legitimate investment vehicles, such as hedge funds that can easily degenerate into a Ponzi-type scheme if they unexpectedly lose money or fail to legitimately earn the returns expected. The operators fabricate false returns or produce fraudulent audit reports instead of admitting their failure to meet expectations, and the operation is then considered a Ponzi scheme.

A wide variety of investment vehicles and strategies, typically legitimate, have become the basis of Ponzi schemes. For instance, Allen Stanford used bank certificates of deposit to defraud tens of thousands of people. Certificates of deposit are usually low-risk and insured instruments, but the Stanford certificates of deposit were fraudulent.[9]

According to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), many Ponzi schemes share similar characteristics that should be “red flags” for investors.[10] The warning signs include:[10]

- High investment returns with little or no risk. Every investment carries some degree of risk, and investments yielding higher returns typically involve more risk. Any “guaranteed” investment opportunity is often considered suspicious.

- Overly consistent returns. Investment values tend to go up and down over time, especially those offering potentially high returns. An investment that continues to generate regular positive returns regardless of overall market conditions is considered suspicious.

- Unregistered investments. Ponzi schemes typically involve investments that have not been registered with the SEC or with state regulators. Registration is important because it provides investors with access to key information about the company’s management, products, services, and finances.

- Unlicensed sellers. Federal and state securities laws require that investment professionals and their firms be licensed or registered. Most Ponzi schemes involve unlicensed individuals or unregistered firms, the few exceptions usually being the aforementioned investment vehicles that started out as legitimate operations but failed to earn the expected returns.

- Secretive or complex strategies. Investments that cannot be understood or do not give complete information.

- Issues with paperwork. Excuses are given regarding why clients cannot review information in writing about an investment. Also, account statement errors and inconsistencies are frequently signs that funds are not being invested as promised.

- Difficulty receiving payments. Clients have failures to receive a payment or have difficulty cashing out their investments. Ponzi scheme promoters routinely encourage participants to “roll over” investments and sometimes promise even higher returns on the amount rolled over.

Theoretically it is not impossible at least for certain entities operating as Ponzi scheme to ultimately “succeed” financially, at least so long as a Ponzi scheme was not what the promoters were initially intending to operate. For example, a failing hedge fund reporting fraudulent returns could conceivably “make good” its reported numbers, for example by making a successful high-risk investment. Moreover if the operators of such a scheme are facing the likelihood of imminent collapse accompanied by criminal charges, they may see little additional “risk” to themselves in attempting cover their tracks by engaging in further illegal acts to try and make good the shortfall (for example, by engaging in insider trading). Especially with lightly-regulated and monitored investment vehicles like hedge funds, in the absence of a whistleblower or accompanying illegal acts any fraudulent content in reports is often difficult to detect unless and until the investment vehicles ultimately collapse.

Typically, however, if a Ponzi scheme is not stopped by authorities it usually falls apart for one or more of the following reasons:[6]

- The operator vanishes, taking all the remaining investment money. Promoters who intend to abscond often attempt to do so as returns due to be paid are about to exceed new investments, as this is when the investment capital available will be at its maximum.

- Since the scheme requires a continual stream of investments to fund higher returns, if the number of new investors slows down, the scheme collapses as the operator can no longer pay the promised returns (the higher the returns, the greater the risk of the Ponzi scheme collapsing). Such liquidity crises often trigger panics, as more people start asking for their money, similar to a bank run.

- External market forces, such as a sharp decline in the economy, can often hasten the collapse of a Ponzi scheme (for example, the Madoff investment scandal during the market downturn of 2008), since they often cause many investors to attempt to withdraw part or all of their funds sooner than they had intended.

Actual losses are extremely difficult to calculate. The amounts that investors thought they had were never attainable in the first place. The wide gap between “money in” and “fictitious gains” make it virtually impossible to know how much was lost in any Ponzi scheme.[citation needed]

In the United States, individuals can halt a Ponzi scheme before its collapse by reporting to the SEC.[11] Under the SEC Whistleblower Program,[12][circular reference] individuals can receive monetary awards for reporting violations of the federal securities laws, including information about Ponzi schemes, if their information leads to a successful SEC enforcement action in which over $1,000,000 in sanctions is ordered. To report a Ponzi scheme and qualify for an award under the program, the SEC requires that whistleblowers or their attorneys report the tip online through the SEC’s Tip, Complaint or Referral Portal or mail/fax a Form TCR to the SEC Office of the Whistleblower.[13]