3.3 Bonds

Personal Finance. Provided by: Saylor Academy. Located at: https://saylordotorg.github.io/text_personal-finance. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

TD Ameritrade: Investing Basics – Bonds (all rights reserved)

https://youtu.be/IuyejHOGCro

Bonds are a relatively old form of financing. Formalized debt arrangements long preceded corporate structure and the idea of equity (stock) as we know it. Venice issued the first known government bonds of the modern era in 1157,Isadore Barmash, The Self-Made Man (Washington, DC: Beard Books, 2003), 55. while private bonds are cited in British records going back to the thirteenth century.George Burton Adams, The Constitutional History of England (London: H. Holt, 1921), 93. Venice issued bonds to raise funds to finance a Crusade against Constantinople, which included expansion of a shipyard attached to the Venetian Arsenal. (Go to http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venetian_Arsenal to view images.)

Bonds

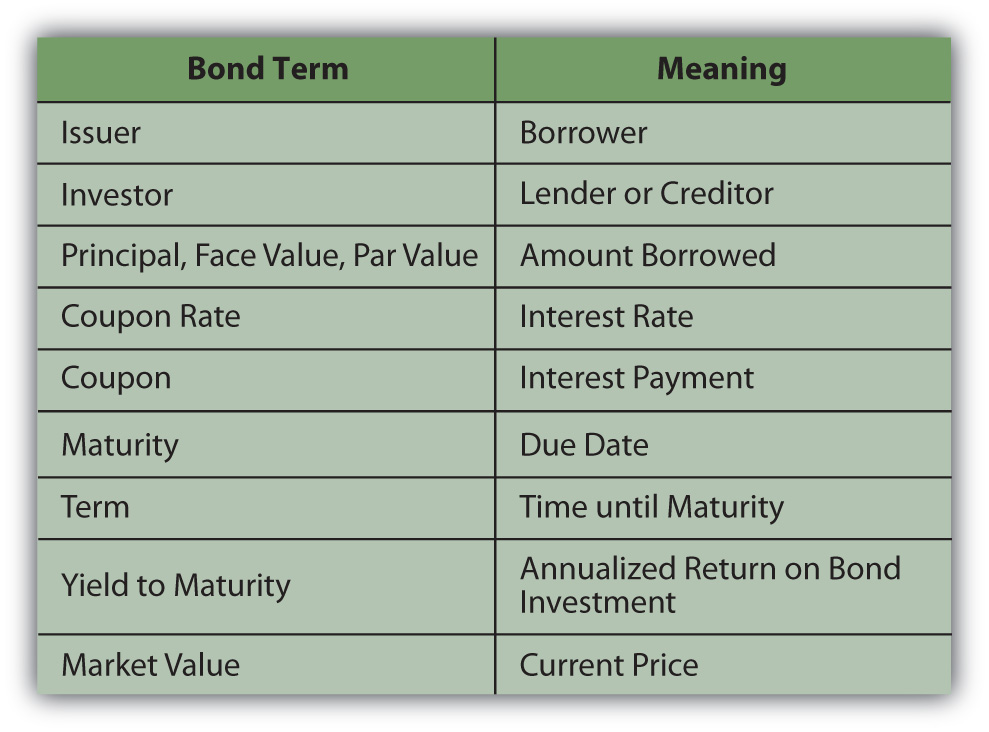

In addition to financing government projects, bonds are used by corporations to capitalize growth. Bonds are also a legal arrangement, couched in conditions, obligations, and consequences. As a result of their legal and financial roles, bonds carry a quaint and particular vocabulary. Bonds come in all shapes and sizes to suit the needs of the borrowers and the demands of lenders. Figure 3.3.1 lists the descriptive terms for basic bond features.

The coupon[1] is usually paid to the investor twice yearly. It is calculated as a percentage of the face value[2]—amount borrowed—so that the annual coupon = coupon rate × face value. By convention, each individual bond has a face value of $1,000. A corporation issuing a bond to raise $100 million would have to issue 100,000 individual bonds (100,000,000 divided by 1,000). If those bonds pay a 4 percent coupon, a bondholder who owns one of those bonds would receive a coupon of $40 per year (1,000 × 4%), or $20 every six months.

The coupon rate[3] of interest on the bond may be fixed or floating and may change. A floating rate is usually based on another interest benchmark, such as the U.S. prime rate[4], a widely recognized benchmark of prevailing interest rates.

A zero-coupon bond[5] has a coupon rate of zero: it pays no interest and repays only the principal at maturity. A “zero” may be attractive to investors, however, because it can be purchased for much less than its face value. If you have a savings bond, then you have a zero-coupon bond!

The face value, the principal amount borrowed, is paid back at maturity. If the bond is callable[9], it may be redeemed after a specified date but before maturity.

Corporations issue corporate bonds, usually with maturities of ten, twenty, or thirty years. Corporate bonds tend to be the most “customized,” with features such as callability, conversion, and covenants.

The U.S. government issues Treasury bills[17] for short-term borrowing, Treasury notes[18] for intermediate-term borrowing (longer than one year but less than ten years), and Treasury bonds[19] for long-term borrowing for more than ten years.

State and municipal governments issue revenue bonds or general obligation bonds. A revenue bond[21] is repaid out of the revenue generated by the project that the debt is financing. For example, toll revenue may secure a debt that finances a highway. A general obligation bond[22] is backed by the state or municipal government, just as a corporate debenture is backed by the corporation.

Interest from state and municipal bonds[23] (also called “munis”) may not be subject to federal income taxes. Also, if you live in that state or municipality, the interest may not be subject to state and local taxes. The tax exemption differs from bond to bond, so you should be sure to check before you invest. Even if the interest is not taxable, however, any gain (or loss) from the sale of the bond is taxed, so you should not think of munis as “tax-free” bonds.

Foreign corporations and governments issue bonds. You should keep in mind, however, that foreign government defaults are not uncommon. Mexico in 1994, Russia in 1998, Argentina in 2001, and Greece in 2009 are all recent examples. Foreign corporate or sovereign debt also exposes the bondholder to currency risk, as coupons and principal will be paid in the foreign currency.

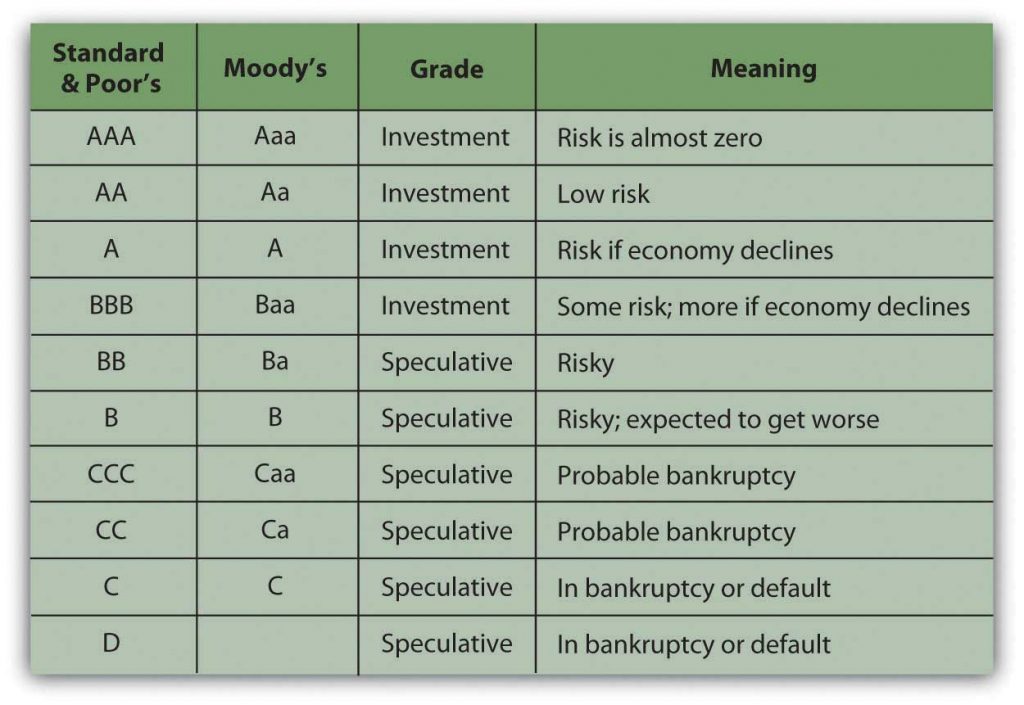

To provide guidance, rating agencies[25] provide bond ratings; that is, they “grade” individual bond issues based on the likelihood of default and thus the risk to the investor. Rating agencies are independent agents that base their ratings on the financial stability of the company, its business strategy, competitive environment, outlook for the industry and the economy—any factors that may affect the company’s ability to meet coupon obligations and pay back debt at maturity.

Ratings agencies such as Fitch Ratings, A. M. Best, Moody’s, and Standard & Poor’s (S&P) are hired by large borrowers to analyze the company and rate its debt. Moody’s also rates government debt. Ratings agencies use an alphabetical system to grade bonds (shown in Figure 3.3.2) based on the highest-to-lowest rankings of two well-known agencies.

A plus sign (+) following a rating indicates that it is likely to be upgraded, while a minus sign (−) following a rating indicates that it is likely to be downgraded.

Bonds rated BBB or Baa and above are considered investment grade bonds[26], relatively low risk and “safe” for both individual and institutional investors. Bonds rated below BBB or Baa are speculative in that they carry some default risk. These are called speculative grade bonds[27], junk bonds[28], or high-yield bonds[29]. Because they are riskier, speculative grade bonds need to offer investors a higher return or yield in order to be “priced to sell.”

Although the term “junk bonds” sounds derogatory, not all speculative grade bonds are “worthless” or are issued by “bad” companies. Bonds may receive a speculative rating if their issuers are young companies, in a highly competitive market, or capital intensive, requiring lots of operating capital. Any of those features would make it harder for a company to meet its bond obligations and thus may consign its bonds to a speculative rating. In the 1980s, for example, companies such as CNN and MCI Communications Corporation issued high-yield bonds, which became lucrative investments as the companies grew into successful corporations.

Default risk is the risk that a company won’t have enough cash to meet its interest payments and principal payment at maturity. That risk depends, in turn, on the company’s ability to generate cash, profit, and grow to remain competitive. Bond-rating agencies analyze an issuer’s default risk by studying its economic, industry, and firm-specific environments and estimate its current and future ability to satisfy its debts. The default risk analysis is similar to equity analysis, but bondholders are more concerned with cash flows—cash to pay back the bondholders—and profits rather than profits alone.

Bond ratings can determine the coupon rate the issuer must offer investors to compensate them for default risk. The higher the risk, the higher the coupon must be. Ratings agencies have been criticized recently for not being objective enough in their ratings of the corporations that hire them. Nevertheless, over the years bond ratings have proven to be a reliable guide for bond investors.