Main Body

3.3 Searching for “Aha!” — College Success

3.3 Searching for “Aha!”

Learning Objectives

- Use creative thinking: the competitive advantage in the twenty-first century.

- Understand the difference between creative thinking and free-form thinking.

- Practice guidelines for creating ideas.

- Use rules and directions to create effectively.

- Understand group creativity: how to conduct effective brainstorming.

America still has the right stuff to thrive. We still have the most creative, diverse, innovative culture and open society—in a world where the ability to imagine and generate new ideas with speed and to implement them through global collaboration is the most important competitive advantage.

Thomas Friedman

Let’s face it: many jobs are subject to outsourcing. The more menial or mechanical the job, the greater the likelihood that there will be someone overseas ready to do the job for a lot less pay. But generating new ideas, fostering innovation, and developing processes or plans to implement them are something that cannot be easily farmed out, and these are strengths of the American collegiate education. Businesses want problem solvers, not just doers. Developing your creative thinking skills will position you for lifelong success in whatever career you choose.

Creative thinking is the ability to look at things from a new perspective, to come up with fresh solutions to problems. It is a deliberate process that allows you to think in ways that improve the likelihood of generating new ideas or thoughts.

Let’s start by killing a couple of myths:

- Creativity is an inherited skill. Creativity is not something people are born with but is a skill that is developed over time with consistent practice. It can be argued that people you think were “born” creative because their parents were creative, too, are creative simply because they have been practicing creative thinking since childhood, stimulated by their parents’ questions and discussions.

- Creativity is free-form thinking. While you may want to free yourself from all preconceived notions, there is a recognizable structure to creative thinking. Rules and requirements do not limit creative thinking—they provide the scaffolding on which truly creative solutions can be built. Free-form thinking often lacks direction or an objective; creative thinking is aimed at producing a defined outcome or solution.

Creative thinking involves coming up with new or original ideas; it is the process of seeing the same things others see but seeing them differently. You use skills such as examining associations and relationships, flexibility, elaboration, modification, imagery, and metaphorical thinking. In the process, you will stimulate your curiosity, come up with new approaches to things, and have fun!

Tips for Creative Thinking

- Feed your curiosity. Read. Read books, newspapers, magazines, blogs—anything at any time. When surfing the Web, follow links just to see where they will take you. Go to the theatre or movies. Attend lectures. Creative people make a habit of gathering information, because they never know when they might put it to good use. Creativity is often as much about rearranging known ideas as it is about creating a completely new concept. The more “known ideas” you have been exposed to, the more options you’ll have for combining them into new concepts.

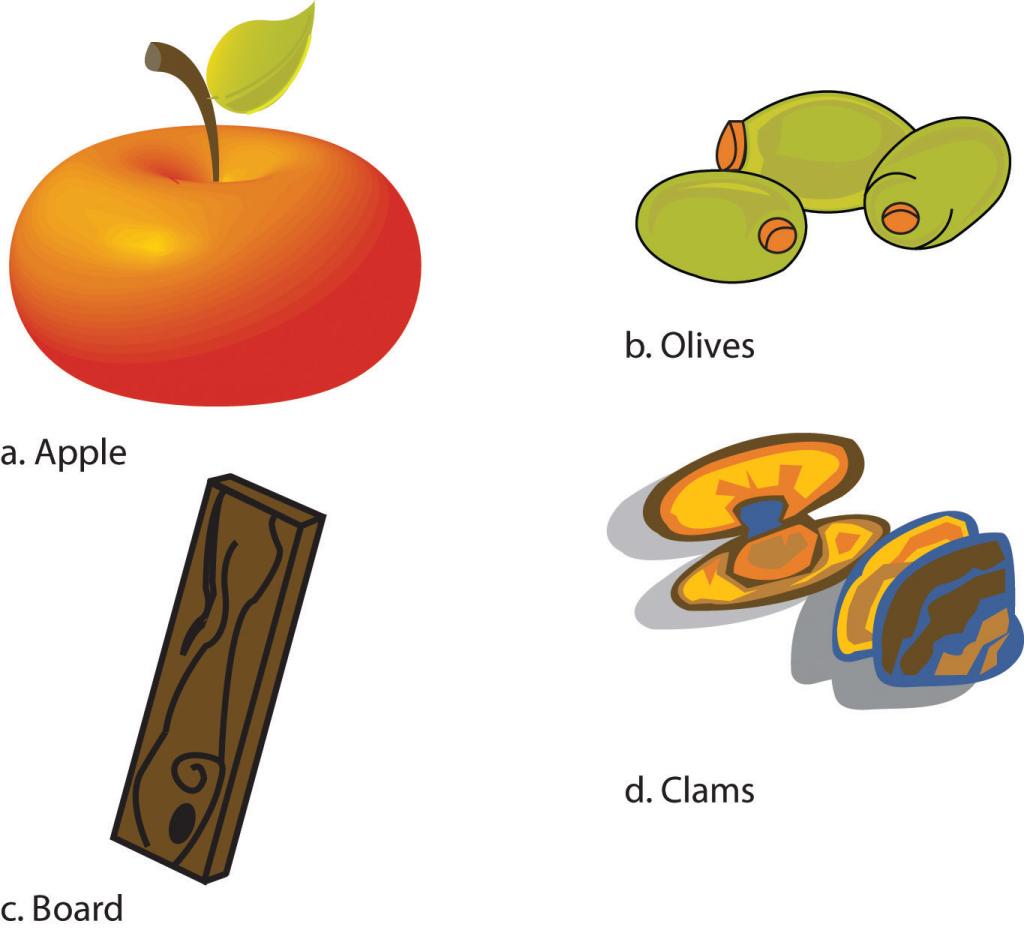

- Develop your flexibility by looking for a second right answer. Throughout school we have been conditioned to come up with the right answer; the reality is that there is often more than one “right” answer. Examine all the possibilities. Look at the items in Figure 3.4. Which is different from all the others?

If you chose C, you’re right; you can’t eat a board. Maybe you chose D; that’s right, too—clams are the only animal on the chart. B is right, as it’s the only item you can make oil from, and A can also be right; it’s the only red item.

Each option can be right depending on your point of view. Life is full of multiple answers, and if we go along with only the first most obvious answer, we are in danger of losing the context for our ideas. The value of an idea can only be determined by comparing it with another. Multiple ideas will also help you generate new approaches by combining elements from a variety of “right” answers. In fact, the greatest danger to creative thinking is to have only one idea. Always ask yourself, “What’s the other right answer?”

- Combine old ideas in new ways. When King C. Gillette registered his patent for the safety razor, he built on the idea of disposable bottle caps, but his venture didn’t become profitable until he toyed with a watch spring and came up with the idea of how to manufacture inexpensive (therefore disposable) blades. Bottle caps and watch springs are far from men’s grooming materials, but Gillette’s genius was in combining those existing but unlikely ideas. Train yourself to think “out of the box.” Ask yourself questions like, “What is the most ridiculous solution I can come up with for this problem?” or “If I were transported by a time machine back to the 1930s, how would I solve this problem?” You may enjoy watching competitive design, cooking, or fashion shows (Top Chef, Chopped, Project Runway, etc.); they are great examples of combining old ideas to make new, functional ones.

- Think metaphorically. Metaphors are useful to describe complex ideas; they are also useful in making problems more familiar and in stimulating possible solutions. For example, if you were a partner in a company about to take on outside investors, you might use the pie metaphor to clarify your options (a smaller slice of a bigger pie versus a larger slice of a smaller pie). If an organization you are a part of is lacking direction, you may search for a “steady hand at the tiller,” communicating quickly that you want a consistent, nonreactionary, calm leader. Based on that ship-steering metaphor, it will be easier to see which of your potential leaders you might want to support. Your ability to work comfortably with metaphors takes practice. When faced with a problem, take time to think about metaphors to describe it, and the desired solution. Observe how metaphors are used throughout communication and think about why those metaphors are effective. Have you ever noticed that the financial business uses water-based metaphors (cash flow, frozen assets, liquidity) and that meteorologists use war terms (fronts, wind force, storm surge)? What kinds of metaphors are used in your area of study?

- Ask. A creative thinker always questions the way things are: Why are we doing things this way? What were the objectives of this process and the assumptions made when we developed the process? Are they still valid? What if we changed certain aspects? What if our circumstances changed? Would we need to change the process? How? Get in the habit of asking questions—lots of questions.

Key Takeaways

- Creative thinking is a requirement for success.

- Creative thinking is a deliberate process that can be learned and practiced.

- Creative thinking involves, but is not limited to, curiosity, flexibility, looking for the second right answer, combining things in new ways, thinking metaphorically, and questioning the way things are.

Checkpoint Exercises

-

Feed your curiosity. List five things you will do in the next month that you have never done before (go to the ballet, visit a local museum, try Moroccan food, or watch a foreign movie). Expand your comfort “envelope.” Put them on your calendar.

- ______________________________________________________

- ______________________________________________________

- ______________________________________________________

- ______________________________________________________

- ______________________________________________________

-

How many ways can you use it? Think of as many uses for the following common items as possible. Can you name more than ten?

Peanut Butter (PBJ counts as one,regardless of the flavor of jelly)

Paper Clips Honors Level: Pen Caps -

A metaphor for life. In the movie Forrest Gump, Forrest states, “Life was like a box of chocolates; you never know what you’re gonna get.” Write your own metaphor for life and share it with your classmates. ____________________________________

-

He has eyes in the back of his head. What if we really had eyes in the backs of our heads? How would life be different? What would be affected? Would we walk backward? Would we get dizzy if we spun in circles? Would it be easy to put mascara on the back eyes? Generate your own questions and answers; let the creative juices flow!

_____________________________________

_____________________________________

_____________________________________

_____________________________________

References

Friedman, T. L., “Time to Reboot America,” New York Times, December 23, 2008, http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/24/opinion/24friedman.html?_r=2 (accessed January 14, 2010).