65 Rationale of UNFCCC and the Kyoto Protocol

“The ultimate objective of this Convention and any related legal instruments that the Conference of the Parties may adopt is to achieve, in accordance with the relevant provisions of the Convention, stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system. Such a level should be achieved within a time-frame sufficient to allow ecosystems to adapt naturally to climate change, to ensure that food production is not threatened and to enable economic development to proceed in a sustainable manner.”

Source: What is the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change?(link is external)

All countries that have signed and ratified the convention agree to general commitments. Specific levels of greenhouse gas concentrations or reductions are not quantified.

The convention distinguished between two types of parties (countries that have ratified the FCCC): Annex I Parties (industrialized countries comprising the OECD countries and ‘economies in transition’) and Non-Annex I Parties (most developing countries). This distinction has been exceedingly important for obligations later identified under the Kyoto protocol.

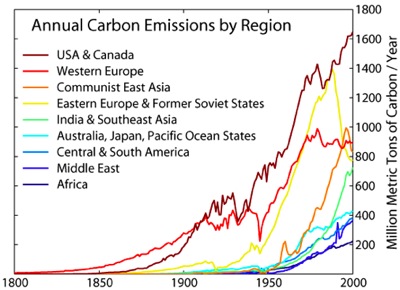

The above distinction is reflected in the figure below, illustrating annual fossil fuel carbon dioxide emissions, in million metric tons of carbon, by region:

The Kyoto Protocol

(Adapted from United Nations Framework Convention on Climate CHange: Kyoto Protocol(link is external))

The Kyoto Protocol is an international agreement linked to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. The major feature of the Kyoto Protocol is that it sets legally binding targets for 37 industrialized countries and the European community for reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. These amount to an average of five percent against 1990 levels over the five-year period 2008-2012.

The major distinction between the Protocol and the Convention is that while the Convention encouraged industrialized countries to stabilize GHG emissions, the Protocol commits them to do so.

Recognizing that developed countries are principally responsible for the current high levels of GHG emissions in the atmosphere as a result of more than 150 years of industrial activity, the Protocol places a heavier burden on developed nations under the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities.”

The Kyoto Protocol was adopted in Kyoto, Japan, on 11 December 1997 and entered into force on 16 February 2005. The detailed rules for the implementation of the Protocol were adopted at COP 7 in Marrakesh in 2001, and are called the “Marrakesh Accords.”

191 states have signed and ratified the Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. The United States is the only major emitter country that has signed but not ratified the protocol.

Flexibility in meeting targets

Emission targets for industrialized country Parties to the Kyoto Protocol are expressed as levels of allowed emissions, or “assigned amounts”, over the 2008-2012 commitment period. Such assigned amounts are denominated in tonnes (of CO2 equivalent emissions).

Industrialized countries must first and foremost take domestic action against climate change, but the Protocol allows them a certain degree of flexibility in meeting their emission reduction commitments through three innovative market-based mechanisms.

The Kyoto Mechanisms

The three Kyoto mechanisms are: Emissions Trading – known as “the carbon market”– the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) and Joint Implementation (JI). The carbon market spawned by these mechanisms is a key tool in reducing emissions worldwide. It was worth 30 billion USD in 2006 and is set to increase.

JI and CDM are the two project-based mechanisms that feed the carbon market. JI enables industrialized countries to carry out joint implementation projects with other developed countries (usually countries with economies in transition), while the CDM involves investment in sustainable development projects that reduce emissions in developing countries.

Since the beginning of 2006, the estimated potential of emission reductions to be delivered by the CDM pipeline has grown dramatically to 2.9 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent – approximately the combined emissions of Australia, Germany, and the United Kingdom. As of 2021, more than 7000 CDM projects have been registered.

What happened in Copenhagen?

The 15th Conference of the Parties in Copenhagen, Denmark (December 2009) was supposed to bring clarity on how countries would agree to pursue emission reductions after 2012. Instead, COP 15 produced a non-binding document, known as The Copenhagen Accord. It recognizes “the scientific view that the increase in global temperature should be below 2 degrees Celsius” although it calls for “an assessment of the implementation of this Accord to be completed by 2015. This would include consideration of strengthening the long-term goal,” for example, to limit temperature rises to 1.5 degrees. No quantified emission reduction goals are included.

Check out this image regarding the Copenhagen conference: Brokenhagen(link is external).

Self-check

Think about your position of what the US should do in the next round of policy negotiations. Do you think the US should commit to more stringent emission reductions than currently proposed by the president (<20%)? Do you think China needs to set a positive example before the US commits to a new treaty? Should developing countries have a right to develop (and emit) just as the industrialized countries did?