Today, the Boston Common is a public park in downtown Boston. It is used in the same ways as any other city park: for leisurely walks, for sports, and for community events.

But the Common was not always used in this way. In the 1600s, long before Boston was a big city, the space was shared as a grazing pasture for cows. The cows were owned by families who lived in the area.

The cow grazing caused a collective action problem. Each individual family wanted their cows to eat as much grass from the Common as they could because then the cows would grow more and be worth more to the family. However, the Common had a finite amount of grass that could be eaten at any one time. Soon the cows were eating the grass faster than it could regrow. At this point, the grazing became unsustainable, and it was only a matter of time before the Common ran out of grass, forcing families to cease grazing their cows.

One could reasonably argue that if the families had collectively established rules for grazing and exercised moderation in their grazing practices, then the grass would not have been depleted, and the cows could have continued grazing indefinitely. However, the original idea behind the “tragedy of the commons” is that the depletion of a shared resource like the Boston Common is unavoidable due to individuals’ selfish behavior.

Defining the Tragedy of the Commons

The term “tragedy of the commons” was coined by Garrett Hardin in his 1968 article published in the journal Science, titled “The Tragedy of the Commons”(link is external). Hardin argued that in the absence of private property rights or strict government regulation, shared resources (i.e., the commons) would ultimately be depleted because individuals tend to act selfishly, rushing to harvest as many resources as they can from the commons.

Often, but not always, certain kinds of limited natural resources are shared by communities because there are significant challenges to establishing and enforcing private property rights. These are called common-pool resources. Fish, forests, and water are good examples of common-pool resources and they are often managed by local communities with or without some government regulation.

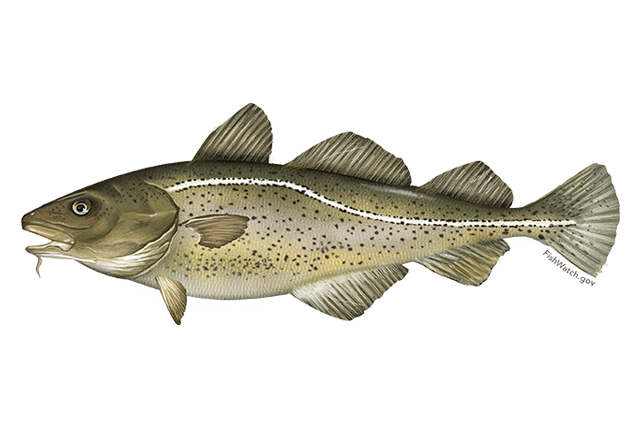

What happened in the Boston Common is one example of the tragedy of the commons. Another important example of the tragedy of the commons is overfishing. Fish can be found in lakes, oceans, rivers, and streams, which are typically not owned by any one person. Anyone can fish in these places, so the places are a “commons” and the fish are a common-pool resource. But there is never an infinite supply of fish. Each individual fisher may want to catch as many fish as he or she can, but if everyone does this, then the supply of fish will be depleted. The depletion is the “tragedy,” and it is unsustainable. Eventually, there will be no more fish, and no one will be able to fish anymore. Additionally, the lack of fish can also have an impact on the rest of the ecosystem. On the other hand, if everyone exercises restraint and doesn’t remove too many fish, then the fish will be able to reproduce, the supply of fish will not become depleted, and fishing can persist indefinitely.

Overfishing is a major global issue. Many fish populations have become severely depleted due to overfishing. One example is the population of cod off the Atlantic coast of the United States and Canada.

Case Study: Atlantic Cod

Between the mid-1970s and early 1990s, a series of poor management decisions and inadequate understanding of complex marine ecosystems led to the collapse of the cod fishery, devastation of livelihoods, a flux of environmental refugees, and long-term impacts on the northwest Atlantic ecosystem off the coast of the northern United States and Canada.

The graph below shows the amount of cod captured and taken ashore (fish landings) between 1850 and 2000. The spike in landings beginning around 1960 was caused by innovations in detecting and capturing cod.

How does that relate to the I=PAT equation?

The smaller increase in landings beginning around 1978 follows the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization (NAFO)’s new program to manage fisheries by adopting fish capture quotas and determined minimum mesh sizes. Notice how both attempts to increase landings were short-lived, and today landings are as low as they’ve ever been.

Figure 4.3 Collapse of Atlantic cod stocks off the East Coast of Newfoundland in 1992

Individual action can help avoid overfishing. For example, you as a consumer can choose to not eat fish whose populations are threatened. The Monterey Bay Aquarium in Monterey, California maintains a Seafood Watch program (link is external)which explains which fish populations are threatened and which are not. The program makes simple guides for each region of the country, available online. (Ask yourself this question: Why does the Seafood Watch program produce different guides for different regions of the country?)

Overfishing can result in permanent collapses in fish supplies. If a population of fish gets completely wiped out, then it cannot reproduce and regrow its numbers, even if people stop fishing entirely. In other words, the collapse can be irreversible. Irreversible collapses can be found in other instances of the tragedy of the commons, including biodiversity loss and certain ecological disruptions. But not all instances of the tragedy of the commons are irreversible. For example, overgrazing in Boston Common causes only a temporary loss of grass, since people can always grow more grass there.

Also importantly, Hardin’s arguments about the tragedy of the commons have been thoroughly analyzed and critiqued. While there are several examples of the tragedy of the commons, there are also numerous counterexamples–cases in which common-pool resources are managed successfully by self-organizing communities of users, without private property rights or strict government intervention. Read on.

A Second Look at The Tragedy of the Commons

As with the neomalthusian IPAT argument, there are many critiques of Hardin’s view of the inevitable depletion of the commons. The first question you should ask when considering a scenario involving the human use of a shared resource is: what is really driving resource depletion? Hardin argues that it is individual selfishness. But take a second look at the Atlantic cod example. It is true that the fishery was massively overfished, leading to a significant collapse of the cod population. But was the overfishing really driven by the individual actions of private fishers, or was it global market forces, large corporate interests, and lax environmental regulations? Remember, the fishers that were bringing in cod in the North Atlantic were not families fishing for subsistence like those keeping a few cattle on the Boston Common. Nor are they small-scale fishers. Commercial fishing like that of the North Atlantic cod is a highly capital-intensive enterprise that involves large boats, significant resources for the time at sea, and corporate contracts. So is this resource degradation a tragedy of the commons, or an inherent problem of capitalism? If you read Hardin’s article in Science, you will notice that he favors, when possible, the enclosure of common resources in favor of private holdings, which is a hallmark of capitalist market economics. This is not to say that capitalism is evil, just that like any other economic system, it is not perfect. And looking past the individual fishers toward larger economic forces is a classic example of using scale in a geographic inquiry. Was it the fishers living and working in the North Atlantic that depleted the fishery, or was it economic processes operating over much larger scales? Or was it some of both?

The second thing to keep in mind when considering the tragedy of the commons is that it has been shown more often than not to be the same sort of doomsaying that we encountered with the IPAT predictions of future human tragedy. It is true that groups of humans do sometimes overuse and exhaust natural resources that could be renewable. But at least as frequently, we see examples of effective institutions for resource governance and stewardship (which we will read more about in the next section). So when seeing something that looks like a tragedy of the commons – like global climate change – perhaps it is not just a problem of individual selfishness. Perhaps an equally significant problem is that the existing systems of governance are not matched to the scale of the problem and are therefore not able to effectively foster successful cooperation.