28 What is Development?

As a geographically literate scholar and citizen, you should be following current events around the world. If you do this, you will undoubtedly hear many discussions of development. You’ll hear discussions of some countries that are “developing” and other countries that are “developed.” You might also hear terms like “First World” and “Third World.” You’ll also hear about how well development in the United States or other countries is going at any given time. Finally, you’ll hear discussions of certain types of development, such as sustainable development. But what does all this mean?

It turns out that “development” does not have one single, simple definition. There are multiple definitions and multiple facets to any one definition. There are also multiple, competing opinions on the various understandings of what “development” is. Often, “development” is viewed as being a good thing, and it is easy to see why. People in “developed” countries tend to have longer lives, more comfortable housing, more options for careers and entertainment, and much more. But whether or not “development” is good is ultimately a question of ethics. Just as there are multiple views on ethics, there are multiple views on whether or not “development” is good. Later in this module, we’ll see some cases in which “development” might not be considered to be good.

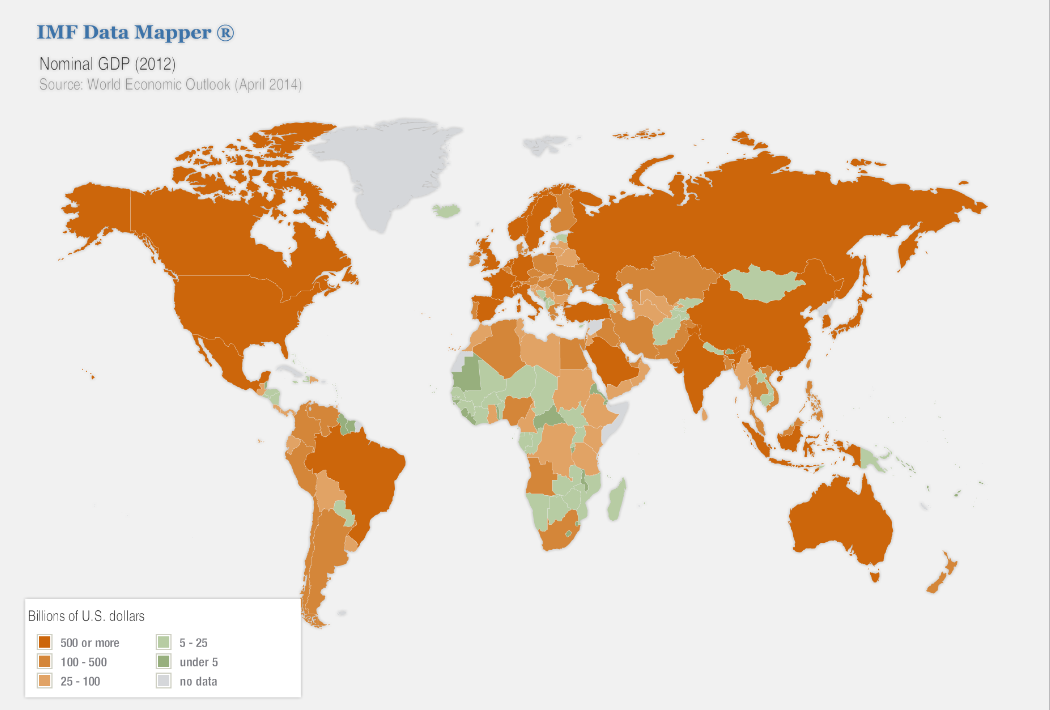

The simplest and most common measures for development are those based on monetary statistics like income or gross domestic product (GDP, which measures in monetary terms how much an economy is producing). These monetary statistics are readily available for countries and other types of places across the world and are very convenient to work with. Likewise, it is easy to find a good map of these statistics, such as this one of GDP:

Figure 5.1 2012 GDP World Map: Countries color-coded by nominal GDP per capita in 2008, IMF estimates as of April 2009.

Take a quick glance at the map in Figure 5.1. What do you see? Does anything interesting stand out? We’ll revisit the map later in the module.

But statistics like income and GDP are controversial. One can have a high income or GDP and a low quality of life. Simply put, there’s more to life than money. Furthermore, monetary statistics often overlook important activities that don’t involve money, such as cooking, cleaning, raising children, and even subsistence farming. These activities are often performed by women, so a focus on monetary statistics often brings large underestimates of the contributions of women to society. Finally, high incomes and GDPs are often associated with large environmental degradation. From an ecocentric ethical view, that is a problem.

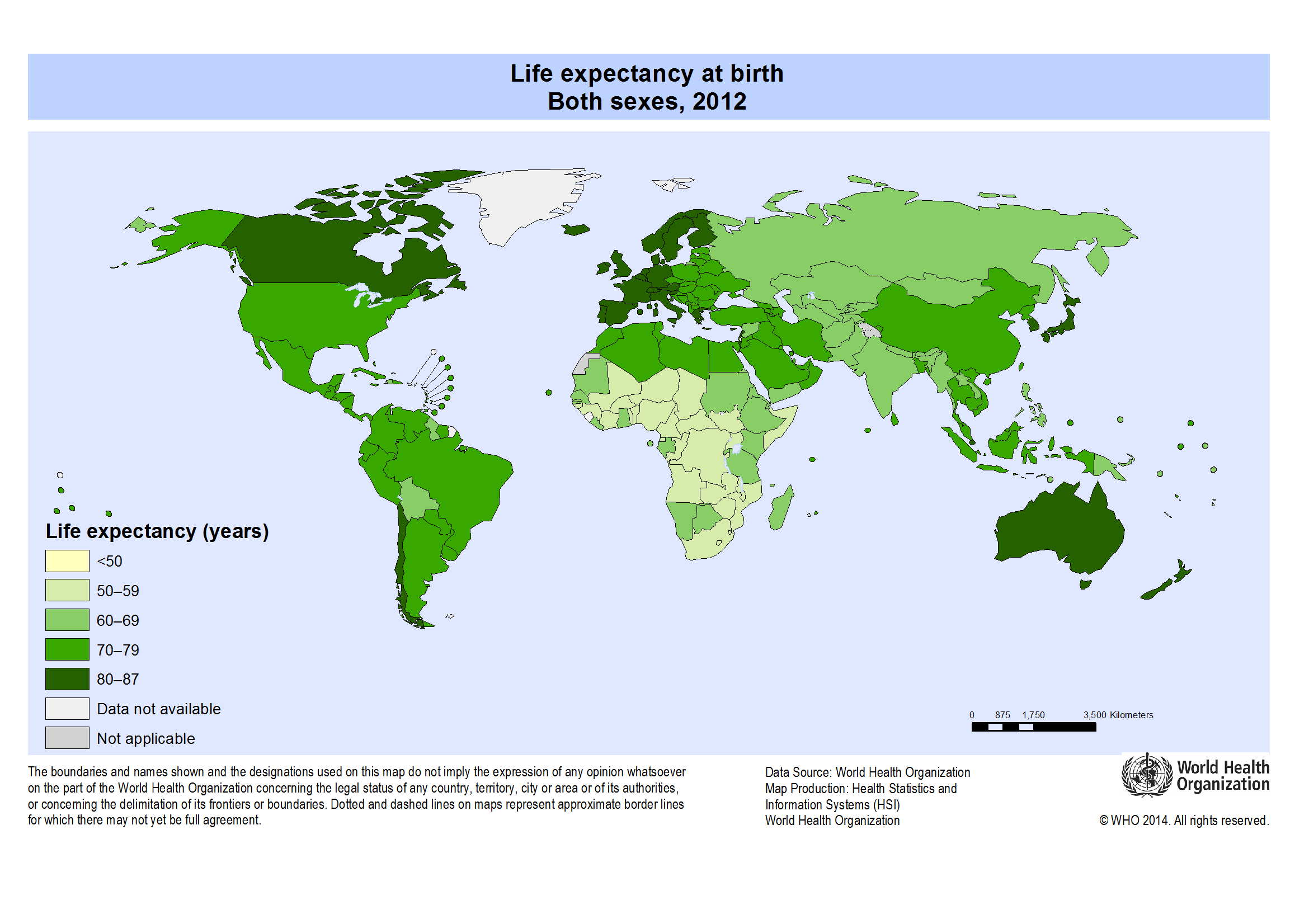

Another way of looking at development is one based on health statistics such as life expectancy or child mortality. These statistics show another facet of development. In many cases, those with a lot of money also have better health. But this trend does not always hold. Take a look at this life expectancy map:

Figure 5.2 Map of World Life Expectancy

How does the Life Expectancy map in Figure 5.2 compare to the GDP map (Figure 5.1)? What patterns are similar? Is there anything different? Why might this be?

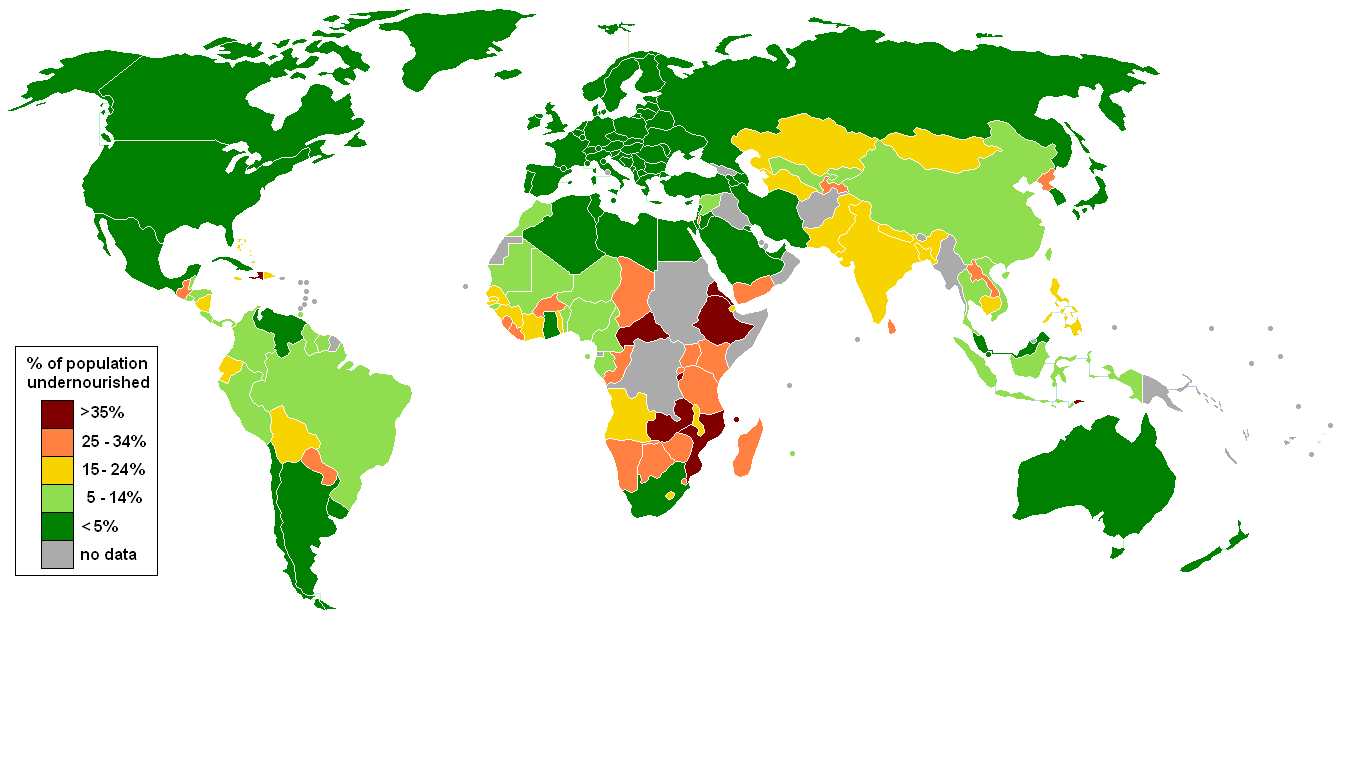

A third way of looking at development is one based on end uses. End uses are the ultimate purposes of whatever our economies are producing. For example, the end uses of agriculture are proper nutrition, tasty eating experiences, and maybe a few other things like the socializing that occurs during meals. The end uses of the construction of buildings involve things like having places for us to be in that comfortable, productive, and beautiful. For transportation, end uses are being in the places we want to be.

Take a look at the following undernourishment map: How does this map compare to the GDP and Life Expectancy map? What patterns are similar? Is there anything different? While most of the world’s undernourished live in low-income countries, is there an exception?

Figure 5.3 2012 Undernourishment World Map: Countries color-coded by percentage of population undernourished.

Reading Assignment: Did the BP Oil Spill Increase US GDP?

Please look at the article “Counting what counts: GDP redefined: what did the BP oil spill in 2010 mean for the U.S. economy?”(link is external) by Ben Beachy and Justin Zorn and/or Oil Spill May End Up Lifting GDP Slightly(link is external) by Luca di Leo of the Wall Street Journal (both are also posted to Canvas in pdf). Even after just several paragraphs of these articles, you should be able to get a sense of what “development” is, in particular, monetary statistics and end uses. Which understandings are better? Is development a good thing? What is it that society should aim for?

At the core of this discussion of development is one very fundamental question: What is it that we ultimately care about as a society? If we ultimately care about money, then the monetary statistics are good representations of development, and we should be willing to make sacrifices of other things in order to get more money. Or, if end uses are what we ultimately care about, then it is important to look beyond monetary statistics and consider the systems of development that bring us the end uses that we want. Modules 6 and 7 do exactly that.

Consider This: A Note On Terminology

Before continuing, let’s pause for a brief note on terminology. Though they are often used as such, the terms First World and Third World are actually not intended to be development terms. Instead, they are a legacy of the Cold War. The First World was the group of major capitalist countries, lead by the United States. The Second World was the group of major communist countries, lead by the Soviet Union. The collapse of the Soviet Union explains why we don’t hear the term Second World much anymore. Finally, the Third World was everyone else, who were viewed as relatively unimportant to the Cold War. These days, the terms First World and Third World are often used not for the politics of the Cold War but for conversations about development. This use of the terms is inappropriate and should be avoided. Another common set of terms is the developing world and the developed world. These terms fit better, though they’re still not perfect. In particular, no part of the world has stopped developing, so, in some sense, all countries are developing countries. Finally, there are no clear divides between the more-developed countries and the less-developed countries, and there are also multiple ways of defining and measuring development. So, a safe choice for terminology is one that precisely describes the type of development you intend, such as high-income countries and low-income countries.