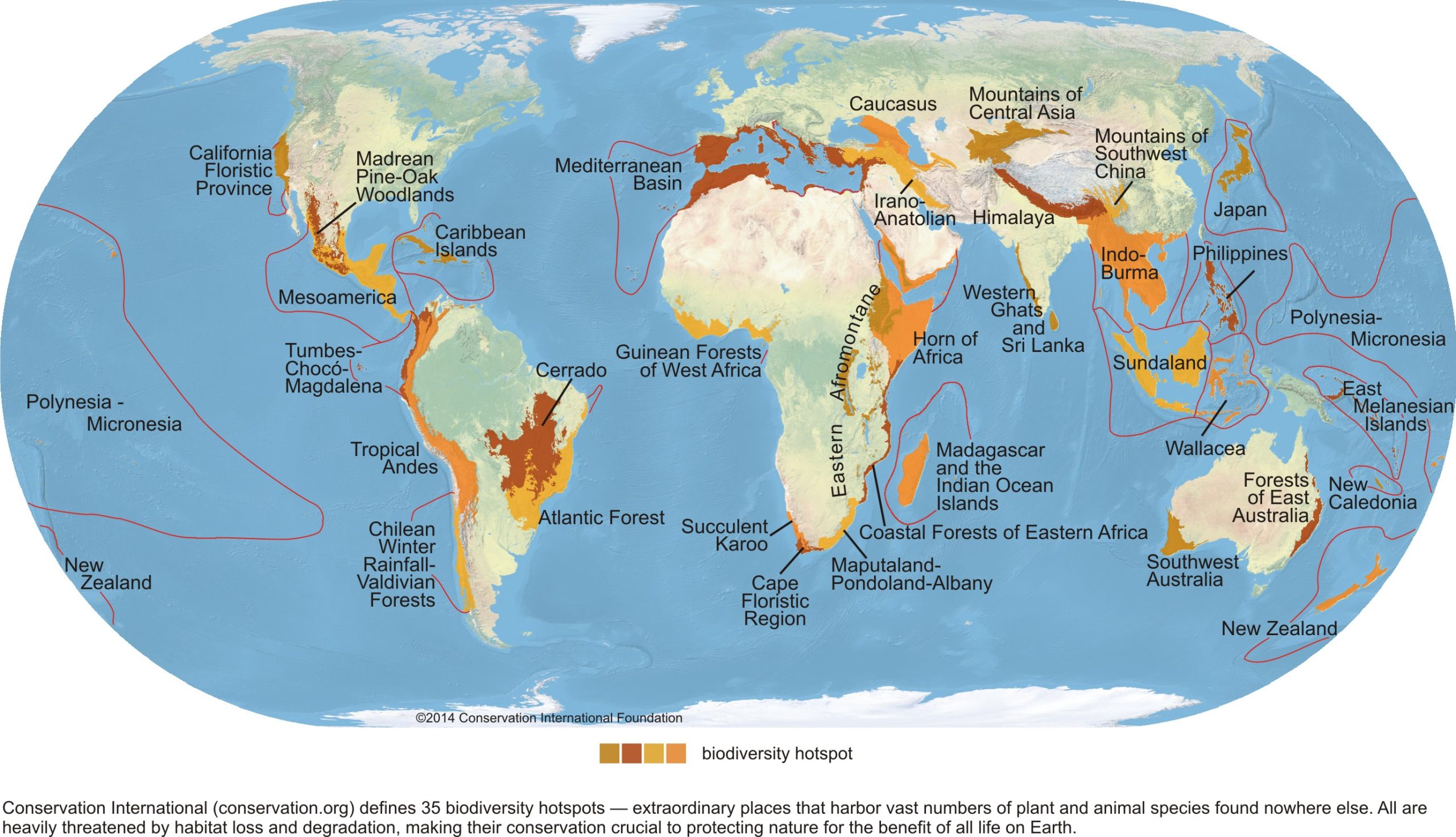

71 Biodiversity Hotspots

A biodiversity hotspot is a region with a high amount of biodiversity that experiences habitat loss by human activity. In order to qualify as a biodiversity hotspot, according to Conservation International(link is external), “a region must contain at least 1,500 species of vascular plants (>0.5% of the world’s total) as endemics, and it has to have lost at least 70% of its original habitat.” Today, 34 hotspots have been identified around the world. While these areas once covered about 16% of the Earth’s land surface, today 86% of their habitat has been destroyed. Even though now hotspots only cover about 2% of the land, 50% of the world’s vascular plants and 42% of land vertebrates are endemic to a hotspot. To get a better understanding of the distribution of biodiversity hotspots around the world, please view the following biodiversity hotspots map produced by Conservation International.

The biodiversity hotspot concept highlights the coupledness of biodiversity and humanity. The concept, first suggested in 1988 by Norman Myers, arose from growing concern among ecologists and environmentalists about the rapid loss of habitat in areas of high biodiversity and endemism. Endemism means that a species only lives in a particular region of the world, which means that if it is wiped out there, it’s lost forever. For example, the now-extinct Dodo bird was endemic to Mauritius, a small island in the Indian Ocean.

One example of a hotspot is the Irano-Anatolian region, which forms the boundary between the ecosystems of the Mediterranean Sea and the plateaus of Western Asia and includes 2,500 endemic plants. Its original extent was about 900,000 square kilometers, stretching from Turkey to Turkmenistan and Iran, but today only about 135,000 square kilometers of original vegetation are left. The most significant threats to this hotspot are large-scale irrigation projects, overgrazing, and unsustainable timber harvesting. The human population has doubled in this region since the 1970s, so even traditional livestock grazing and wood-gathering practices have put increased pressure on the region’s resources. Huge areas of swamps have been drained and converted to growing sugar beets and other crops using industrial agricultural methods. The political instability of the region and active military conflicts also undermine conservation efforts.

A Historical Perspective on Biodiversity Loss

About 99.9% of species that have ever lived on earth are now extinct, but at the same time, there are likely more species alive during the current era in geological history than at any previous time. Why is this?

Since the first cellular life appeared about 3.8 billion years ago, new life forms have been constantly evolving and some species have been going extinct. Since life on Earth is so old, most of the species that have ever lived are now gone, even if they persisted for millions of years. There have been periods of biodiversity explosions, as well as periods of mass extinctions, but generally, the trend has been toward an increase in the variety of life forms on this planet. Speciation rates (the rates of new species coming into existence) are high following mass extinction events and have been increased by the evolution of body types that allow animals to inhabit all types of habitats like deserts, soils, thermal ocean vents, and the sky. Also, the breaking up of Pangaea into separate continents has fostered an explosion in the number of species on Earth.

We should realize that humans are not responsible for most of the extinctions that have happened on Earth. At the same time, humans have been influencing biodiversity for a long time, and human-caused extinctions are not a new thing at all.

Early Anthropogenic Extinctions

During the end of the last ice age (known as the Pleistocene), about 10,000 to 15,000 years ago, many of the large mammals, birds, and reptiles, collectively known as megafauna, went extinct in North and South America. Mastodons, mammoths, giant beavers, and saber-toothed tigers, along with many other species, disappeared in a fairly short period of geologic time.

While we do not have direct evidence of what caused their extinction, most researchers believe that overharvesting of wildlife by humans played a decisive role in many extinctions. The extinctions roughly coincide with the arrival of humans into the Americas, and a similar story is apparent in Australia, although human arrival there was much earlier.

It is important to note that during this period the climate was warming rapidly (due to natural, not human causes), and vegetation was changing as a result. Therefore, humans were not the only stress that may have damaged populations of these megafauna species. On the other hand, these species had persisted through significant climate fluctuations in the past, and the major new factor when they became extinct was the presence of humans.

Another striking example of human-caused biodiversity loss from before the modern era comes from Polynesia in the southern Pacific Ocean. Humans caused the extinction of over 2000 species of birds as they colonized these tropical islands between 1000 and 3000 years ago. Among the factors causing extinction were direct harvesting, habitat alteration, and the introduction of predators like pigs and rats. Flightless birds were particularly vulnerable to human and non-human hunters, and many of them went extinct.

One important lesson to draw from these two examples is that even people whom we identify as “native” or “indigenous” to a place can cause extinctions. It can be tempting to imagine that Western civilization, capitalism, or other “modern” ideas or technologies are the root cause of biodiversity loss, but that belief is not supported by this history. It is vital that we view indigenous peoples not as somehow “one with nature” or in perfect harmony with their ecosystems, but as dynamic and diverse human cultures that have long played important roles in shaping the landscapes that they inhabit. That said, there are valuable lessons that we can learn from indigenous cultures about how to maintain functioning ecosystems and biodiversity while providing for basic human needs.

European Colonialism

The above example of Polynesian colonialism was a precursor to the massive colonial efforts by European nations from the 1400s through the 1800s. European colonialism had massive impacts on biodiversity through the exchange of species between Europe and colonized regions, the conversion of habitat, and over-harvesting of species that led to extinction.

The transfer of plants, animals, and microbes between continents during this era are known as the “Columbian Exchange.” One of the most dramatic impacts of this exchange were the introduction of European diseases into Native American populations that had no immunities to them. These diseases caused declines in indigenous populations of up to 90% in some cases, crippling social systems, and subsistence harvesting, altering long-established practices like burning and agriculture, and leading to large cities simply disappearing in many parts of the Americas. Because of these diseases, much of the interior regions of North and South America became much less populated than they had been for thousands of years.

The “hollowing out” of the interiors of these continents had a serious impact on the processes of colonial settlement, both in the past and today. In North America during the 1700s and 1800s, many European settlers interpreted the regions they were moving into as an “untouched wilderness,” when, in many cases, those areas had a long history of habitation and alteration by Native American groups.

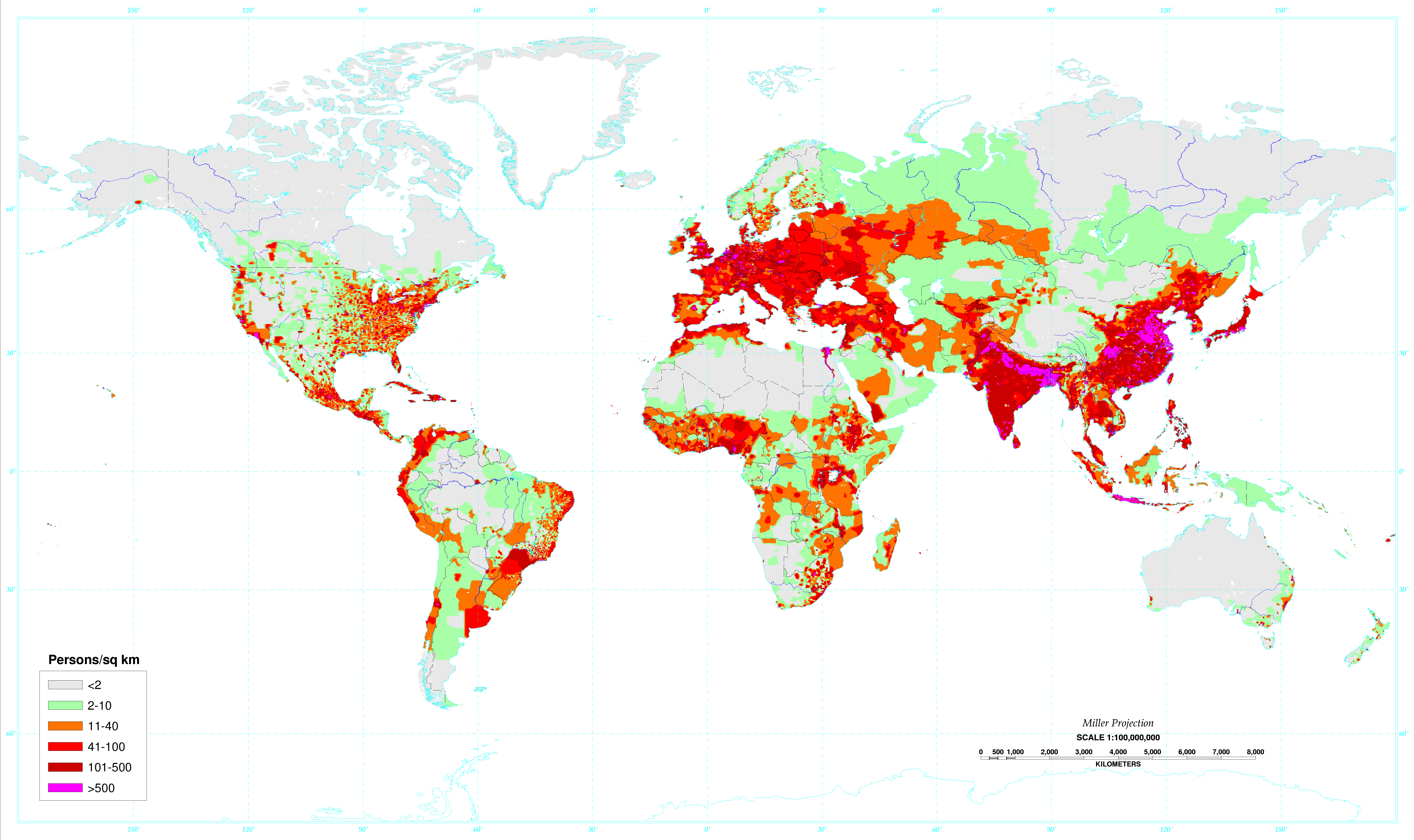

In South America, the impacts of European diseases are perhaps even more evident today. We don’t have precise data on population levels in the Amazon River Basin prior to European settlement, but the best estimates are that about 10 million people lived in the region. There were cities, villages, and intensive agricultural areas, as was true of many other biologically rich places in the Western Hemisphere at that time. During the 1600s and 1700s, diseases brought by European explorers wiped out 90% of Amazon residents, leaving less than one million. During the subsequent centuries, descendants of the Spanish and Portuguese colonists have built large cities like Rio de Janeiro, Lima, and São Paulo along the coasts, while the population of the interior Amazon region remains low. The world map of population distribution below shows that South America remains a “hollow continent” today.

In this light, we should not think of the Amazon rainforest as a “virgin wilderness,” but as a long-humanized landscape that has only recently grown back into a wild state. Without the influence of European diseases, South America’s demographics and environments would look much different. This is a reminder that we can never ignore history when trying to understand complex human-environment systems.

European colonialism also led to habitat modifications on an unprecedented scale, which had serious negative impacts on biodiversity. One key example is deforestation in North America. Native Americans made noticeable alterations to the temperate forests of North America through burning the understory and clearing patches of forest to grow maize and other crops, but their modifications are eclipsed by the systematic destruction of forests by European colonists.

Consider This: Deforestation in the United States

Deforestation was driven largely by a desire for cleared agricultural land, but also by the needs of manufacturing industries. In Pennsylvania (literally “Penn’s Woods”), much of the forest was cleared and turned into charcoal to fuel iron furnaces. While today much of Pennsylvania has reforested, during the past 200 years almost every forest in the state has been cleared, some multiple times. While biodiversity has benefited from forest regrowth in many places in North America, often new forests do not have the same level of biodiversity as their predecessors, and some areas remain agricultural lands or urban developments with low levels of biodiversity.

Consider the map of the history of deforestation in the United States below. The map focuses on areas of “virgin forests,” otherwise know as old-growth or primary forest, and so it doesn’t show us where forests have grown back. Nevertheless, it’s useful because it mirrors a process that is going on today: the cutting of the Amazon rainforest in South America. While many people in the U.S. bemoan the destruction of the Amazon today, that deforestation follows in the footsteps of the U.S., Europe, and other “developed” nations. We want to be careful to remember not to point fingers of blame at developing countries in the tropics as the main causes of deforestation because that would ignore our own history.

One of the most important lessons that we should learn from biodiversity hotspots is that biodiversity cannot be fully understood without considering factors like human population, agricultural techniques, military activities, and political systems. Biodiversity is entangled with human influences. At the same time, human economic, social, and political systems cannot be understood outside the context of the diverse life forms that support our existence.