13 Gender, Agriculture, and Development

Hazel Velasco Palacios; Alfredo Reyes; and Paige Castellanos

Learning Objectives

At the end of the chapter, students will be able to:

- Explain the differences between gender and sexual identity.

- Identify and contrast the different development approaches to gender and agriculture.

- Understand the main components of the gender asset gap and the gap’s implications for agriculture and rural development.

- Discuss the relevance of women’s empowerment in agriculture and how it relates to international development.

Introduction

Improving women’s empowerment and reducing gender-based inequalities are central goals of global development policy. This chapter explores changes in gender and development frameworks. We cover diverse geographic areas, including Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean, but pay particular attention to the Global South. We begin this chapter by introducing some important concepts, including sex and gender, that help elucidate the role of gender in agrarian societies.

We then present the characteristics of the main approaches to gender used in international development over the past decades. Drawing on the work of pioneering academics such as Boserup, Agarwal, Kabeer, Mohanty, and Shiva , we focus on the role of women in agriculture. Throughout the chapter, we discuss some of the overarching gendered dimensions of agriculture and the work that is currently being done by research institutes to advance our understanding of the issue. We argue that to achieve a more just society, it is critical to understand gender roles; their intersection with other identity markers including age, class, marital status, ethnicity, and migration status; and their effects on people’s lives.

What Is Gender?

The words “sex” and “gender” are often thought to be synonymous. However, whereas anatomical sex refers to biological characteristics, like external anatomy, chromosomes, and hormones (Killermann, 2017), gender refers to the social construction of features, roles, responsibilities, rights, and behaviors (Quisumbing, 1996). Gender differences are observed in every society, but their expression can vary quite widely depending upon the culture and time. Gender markers include “man,” “woman,” and a number of non-binary terms. Gender identity is one’s perception of their gender and may either align (cisgender) or not align (sometimes referred to as trans*), in varying degrees, with one’s anatomical sex.[1] Since gender is a social phenomenon, changes in gender norms, which are expectations for behavior based on gender, can be achieved through deliberate social actions such as policymaking (Food and Agriculture Organization [FAO], 2011).

Anatomical sex is biology. Gender is sociology. Gender roles are constantly being challenged and changing.

Gender and Development Approaches

Having discussed the difference between sex and gender, we review how these terms have been applied to the context of international development. We present a summary of the main approaches to incorporating gender into development strategies, including their origins, assumptions, and shortcomings. Gender approaches serve as lenses through which gender inequalities are framed and potential solutions are proposed. Over time these trends influence policy, program investment, and research at the global, national, and even community levels.

Women in Development

The women in development (WID) approach is epitomized by Ester Boserup’s Women’s Role in Economic Development. Boserup (1970) researched the transformations that men and women working in agriculture experienced when their societies shifted from traditional to modernized agricultural practices. She showed that in less populated African regions where slash and burn agriculture was common, women did most of the agricultural work. On the other hand, in densely populated areas where modernized agriculture tools (e.g., the plow) took hold, men did more agricultural work. For Boserup, through the modernization process and the introduction of Westernized land ownership laws, women lost their access to land and accordingly their control over agriculture.

In the United States, the feminist movement saw legislative and administrative measures in favor of women’s economic integration as the solution to the disparities emerging from modernization (Rathgeber, 1990). At this time, most saw development as a linear, staged process through which societies transformed from agricultural, rural, and traditional ones to post-industrial, urban, and modern ones (Ynalvez & Shrum, 2015). This influenced the preference towards incorporating women into the economy. It was assumed that the only way to achieve higher living standards in “developing” countries was by modernizing their economies. From the 1950s through the 1970s, this assumption spread throughout the international development world.

The WID approach has been criticized for its strong focus on implementing technological fixes to societal problems that tend to be more complex than imagined.

In stressing the need for women to earn income through productive work, the WID approach overlooked the burden that reproductive responsibilities (domestic activities intended to nurture and maintain human life) placed on women (Rathgeber, 1990). Moreover, this approach suggested that all women face the same challenges by virtue of their gender (Mohanty, 1984).

Women, Environment, and Development (WED)

The women, environment, and development (WED) perspective was strongly influenced by Vandana Shiva’s work on ecofeminism. Shiva’s Staying Alive: Women, Ecology, and Development (1989) emphasizes women as inherently closer to nature than men. In her book, Shiva holds that women and nature both share histories of oppression by patriarchal institutions and the dominant Western culture. In this sense, the hope for environmentally sustainable and egalitarian development lies in the incorporation of feminine ways of connecting with nature.

The WED perspective runs parallel with the WID approach, sharing the latter’s strong focus on women’s activities, with men barely figuring into the picture. Furthermore, as with the WID perspective, the WED approach tends to portray women as a homogeneous group. According to Leach (2007), the relationship between the two perspectives can be seen as a translation of WID perspectives into the environmental domain. One of the biggest critiques of the WED approach stems from its essentialist view that women’s relationship with nature is innate.

The WED perspective understands that women care for the environment as an extension of their caring roles for their families linked with ideas of maternal altruism (Nightingale, 2006).

This view of women’s closeness to nature is blind to the other factors that have pushed them closer to it, such as women’s lack of access to alternatives and women and men’s unequal power relations. These differences can also be explained by context-specific norms and socially constructed gender roles.

Women and Development (WAD)

The WAD approach[2] emerged from concerns about the limitations of modernization theory (Rathgeber, 1990). This perspective was developed in the second half of the 1970s. Unlike the WID approach, the WAD perspective suggests that women have always been part of development processes and the economy. This approach assumes that women’s position can be improved by creating more equitable international structures.

The WAD approach includes men in analysis and acknowledges that they are also affected by structural inequalities at the international level and by class and status at the local level.

Although Rathgeber (1990) saw the WAD perspective as more critical of women’s position than the WID approach, the WAD approach still did not sufficiently explain the relationship among patriarchy, differing production models, and women’s subordination and oppression. However, both perspectives emphasize the need for interventions to develop income-generating activities without considering the time burden these activities will place on women. As a result, both approaches fail to recognize how their understanding of development creates new problems in women’s lives in the long run. Chowdhury (2015) explained that the ideology of motherhood was incorporated into development by Western experts, who assumed that women were exclusively mothers. This understanding of motherhood resulted in Western biases and assumptions about women’s roles in the Global South, including the belief that the tasks carried out in the household have no economic value.

Gender and Development

The gender and development (GAD) approach emerged in the 1980s. With its roots in socialist feminism, this approach bridges the gap found in modernization theory by connecting production and reproduction (Rathgeber, 1990). Moreover, the GAD approach examines the overall structure of society taking economic and political factors into account to show how certain aspects of society function.

The GAD approach does not examine women exclusively; instead, it explores how gender as a social construction is used to assign women and men different roles, responsibilities, and expectations in the world.

Other aspects of the GAD approach to highlight are that it recognizes women’s agency (ability to control one’s own actions) and sees women as agents of change, not as passive recipients of development assistance. The GAD perspective has a strong focus on strengthening women’s legal rights; this includes the reform of inheritance and land laws. One of the principal challenges of the GAD approach is turning its goals into activities that can support the changes it proposes in the long run.

Gender Transformative Approaches

Gender transformative approaches (GTA) claim to present an alternative to “business as usual” in gender and development (Wong et al., 2019). This perspective stems from feminist scholars’ critiques of the unexpectedly harmful outcomes of international development work. Several of the considerations reflected in this approach were voiced by Mohanty (1984), who criticized western development. Mohanty highlighted that development promoters stereotyped women as a homogenous group, adopted methods that reinforced universal and cross-cultural application and validity, and created a single form of oppression. In this sense, GTA proponents seek to improve development outcomes by implementing structural changes that fully address gender inequalities.

Thus, GTA tries to avoid simplistic definitions of women’s and men’s roles and the construction of gender. In this sense, “business as usual” gender and development practice (WID, WED, WAD), which is the common framing of gender analysis, is focused on “gaps.” The problem with addressing those gaps is that it entails looking at the disease’s symptoms, not the cause. In other words, we examine how inequality appears while ignoring the structural factors that caused it.

“Business as usual” gender and development practices also emphasize the differences between women and men, with a particular focus on unequal access to resources. This approach carries the significant risk of putting women and men into categories while putting aside “other intersecting social dimensions such as age, social status, race, ethnicity, etc.” (Wong et al., 2019) .

GTA highlights structural changes required to achieve more equitable gender relations: the disruption of the gender status quo by questioning power, privilege, and the status of the dominant group, formed primarily by men.

One of the primary risks of applying the GTA approach is veering too far from its key tenets. The ideas framed in the GTA approach can be easily diluted during the design and implementation process of a development project due to time constraints, the length of funding cycles, and the need for longer time periods, more resources, and specialized facilitators (Wong et al., 2019). Understanding the attributes and differences among the various approaches to gender development is important for practitioners and researchers.

Gendered Dimensions of Agriculture

Gender Roles

By examining the trajectory of gender and development frameworks, we can better understand the importance of applying a gendered lens to global agriculture. We now look more closely at gender roles in agriculture and food systems. Agrarian settings are often seen as bastions of traditional family structures, thought to feature heterosexual partnerships with clearly defined labor divisions based on sex and age (Sachs, 1996). While farming and the idea of “farmer” have long been associated with men, women play a key role in food systems and are gradually identifying more as farmers (Allen & Sachs, 2007; Brasier et al., 2014). In addition, recent research indicates that what it means to be a farmer is changing. As capitalist agriculture expands, the family farm is reshaped, and so too are the views on gender and sexuality and more specifically on heteronormativity (the assumption that heterosexuality is the norm; Leslie, 2017). Over time, alternative food systems have also shed light on the often-overlooked presence of LGBTQ+ individuals in rural spaces and agrarian settings (Hoffelmeyer, 2021).

Nevertheless, worldwide farming systems still favor heterosexual cisgender men. Multiple studies have found that farmers who do not self-identify as cisgender men (women and queer people) often experience many more systemic barriers to engage and be successful in agriculture (FAO, 2018; Quisumbing et al., 2014; Sachs, 2014; Trauger et al., 2010). While studies expanding our understanding of gender identity and sexual orientation are growing, it remains limited and somewhat restricted by context. Given this chapter’s scope, most of the literature on agriculture and gender presented is framed using men’s and women’s roles.

Gender Disparities in Food Systems

In discussing agriculture and food security, we must recognize both the critical role of women in agriculture and the gender disparities that exist globally. According to the Food and Agricultural Organization’s (FAO) The Status of Women in Agrifood Systems (2023), women make up approximately 40% of the agricultural labor force and in Sub-Saharan Africa nearly 50%. Furthermore, approximately 36% of working women and 38% of working men work in agrifood systems. While this represents a global decline, largely due to a reduction in labor in primary agriculture production, this remains a major source for the livelihoods of women and men in many parts of the world. Women have always been active in agriculture, but their contributions have not always been recognized. The shift in women’s role in agriculture is often referred to as the feminization of agriculture. It is perceived to be driven by men’s outmigration in many rural places; however, women are also able to take advantage of new employment opportunities and actively engage in farming decisions (Kawarazuka et al., 2022). Women and women farmers play a key role in local, sustainable agriculture (Sachs et al., 2016) as well as diverse sectors such as fisheries and forestry (Agarwal, 2018).

Despite their contributions to food production, women are more likely to experience food insecurity. Reports indicate that nearly 150 million more women than men experienced hunger in 2021, amid the COVID-19 pandemic (CARE Evaluations, 2022). Women are also more likely to face low-wage, informal, and precarious working conditions (FAO, 2023). Women who work in agriculture often do so in disadvantaged conditions. This may put them at increased risk of experiencing gender-based violence, sexual harassment, and both psychological and physical abuse (FAO, 2023). In addition to performing agricultural labor, women and girls bear a disproportionate amount of the unpaid care work burden, taking care of family members, cooking, and cleaning and thereby providing tremendous amounts of invisible support to the global economy and agriculture sector (Oxfam, 2020).

Access to Resources

Agriculture is an activity that often requires access to many resources and inputs. Studies have shown that the distribution of household assets has a major effect on outcomes such as food security, nutrition, and education (Deere & Doss, 2006; Johnson et al., 2016; Quisumbing et al., 2014). However, one of the main contributions of feminist scholars has been to show that household and individual assets are not necessarily the same and we cannot assume even within a household that women are able to have access to assets (Agarwal, 1988). Designing effective development policies and interventions requires a thorough understanding of how gender interacts with asset distribution within a household, impacting livelihoods and bargaining power (Coles & Mitchell, 2010). We examine the evidence available regarding the distribution of assets by gender around the world and how it relates to women’s empowerment. We recognize that people are assigned various roles and responsibilities due to gender norms that are set at the individual, household, community, and societal levels. Gender roles can also determine the material and non-material resources a person can access, such as land, credit, technical information, and political power. This unequal access impacts people’s daily lives and limits their capacity to thrive by limiting their access to education or employment opportunities.

Gender Asset Gap in Agriculture

Individuals and households hold and invest in different types of assets, including tangible assets like land, livestock, and machinery and intangible assets like education and social networks.

Assets are more than just resources that allow people to survive; they also give meaning to people’s lives and give them the capacity to act (Bebbington, 1999). These different forms of asset holdings have been categorized by Quisumbing et al. (2014) as follows:

- Natural resource capital: land, water, trees, genetic resources, soil fertility

- Physical capital: agricultural and business equipment, houses, consumer durables, vehicles and transportation, water supply and sanitation facilities, and communications infrastructure

- Human capital: education, skills, knowledge, health, nutrition

- Financial capital: savings, credit, and inflows (state transfers and remittances)

- Social capital: membership in organizations and groups, social and professional networks

- Political capital: citizenship, enfranchisement, and effective participation in governance

The empirical evidence indicates that worldwide, social norms significantly limit women’s ownership and control over assets.

THE GENDER ASSET GAP IN NUMBERS

“According to Antonopoulos and Floro (2005), on average in Thailand, men’s assets are higher than those of women. Additionally, Quisumbing and Maluccio (2003) found that in countries like Ethiopia, Bangladesh, and Indonesia, men bring more wealth to marriage than women. In Brazil, Nicaragua, Mexico, and Paraguay, men accounted for a greater proportion of property owners and on average owned more land (Deere and León 2003). Within Ghana, Kenya, Northern Nigeria, Mexico, and urban Guatemala, it is documented that men owned more assets than women (Deere and Doss 2006). Furthermore, in many countries, an important gender-based gap exists in formal education. For instance, in Ghana, Uganda, Cambodia, India, Guinea, Bolivia, and Iraq, men still have on average at least 1 year more schooling than women, while in other countries, the gap is between 0.6 and 0.8 years (Hausmann et al., 2010).”

Source: Quisumbing et al., 2014, p. 95

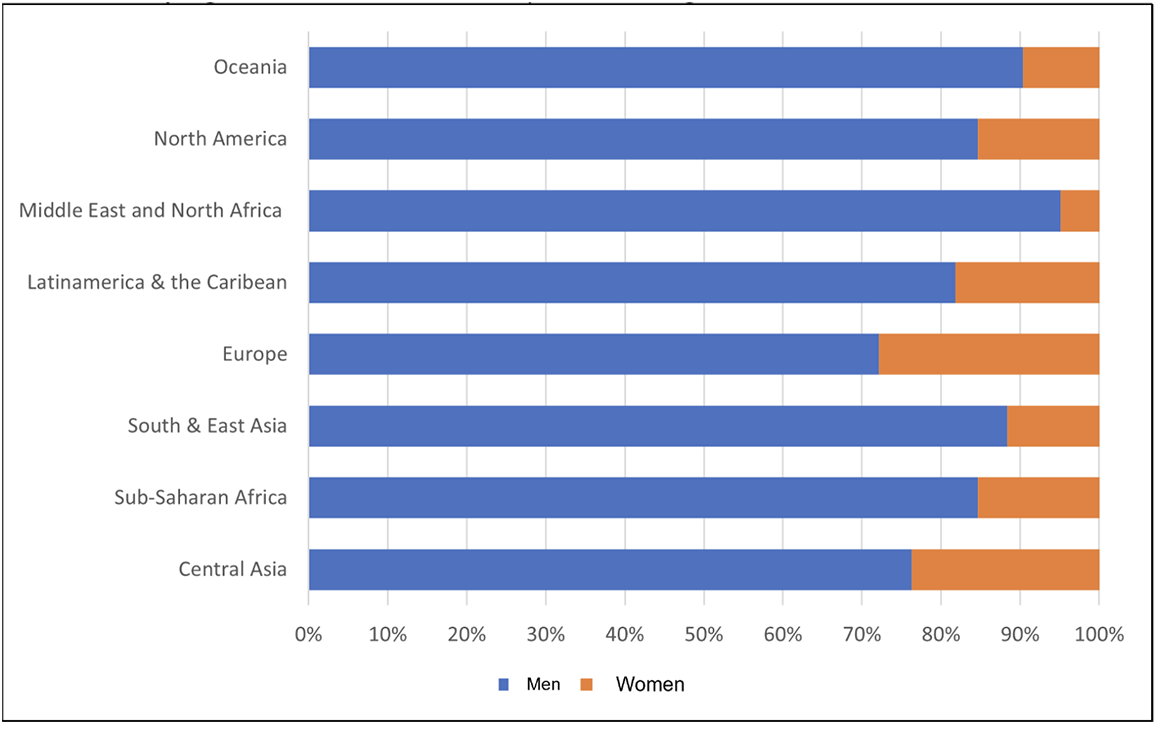

Studies on gender and agriculture have persuasively demonstrated the differences between women and men in access to land, training, formal and non-formal education, credit, and other resources that are needed to succeed in agriculture (Sachs et al., 2020). Although research has shown that increasing women’s control over land and other assets has various positive effects on food security, child nutrition, education, and women’s own well-being (Meinzen-Dick et al., 2014), women’s access to land (one of the central assets in agriculture) at a global level is still unequal (Figure 1). Research can help elucidate how existing formal (laws) or informal (social norms) systems influence women’s access to assets, and the findings from such studies can help promote policy and development interventions that favor women’s equality.

Figure 1

Distribution of Agricultural Land Holders by Sex and Region

Development Interventions: The Gender, Agriculture, and Assets Project

To understand better how development interventions can contribute to women’s equity in agrarian communities, the International Food Policy Research Institute and the International Livestock Research Institute conducted the Gender, Agriculture, and Assets Project (GAAP) from 2010 to 2014.

The GAAP research team members worked with eight agricultural development projects in Africa and South Asia to identify how such projects impact men’s and women’s assets.

The specific objectives of the project were “to identify strategies that successfully build women’s assets and reduce gender gaps in asset access, control, and ownership; and to improve each participating organization’s abilities to measure and analyze qualitative and quantitative gender and asset data” (Johnson et al., 2016, p. 297). The GAAP results indicated that the ability of development projects to benefit women may be improved through greater recognition of the importance of assets as well as attention to gender and asset ownership issues in the design, implementation, and evaluation of projects. GAAP contributed significantly to the study of gender and assets in the Global South. It demonstrated that collecting disaggregated asset data on women and men within a development context is feasible and useful, and moreover, even in projects that do not transfer assets, asset measures are sensitive to change within project time frames.

The lessons of GAAP on recognizing, measuring, and accounting for assets have led to a wide-ranging discussion and implementation of research resources (both qualitatively and quantitatively) and have been developed into a toolkit for gender and development (Quisumbing et al., 2012). The GAAP lessons also facilitated the development of the Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (Alkire et al., 2013), a tool that reaffirms how important it is for development interventions to focus on women’s empowerment, which includes increasing women’s control and ownership of assets, especially for agriculture development projects.

Empowerment and Beyond

Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture

Empowering women and reducing gender-based inequalities are central goals of development policy. Kabeer’s (1999, p. 435) definition of empowerment as “the process by which those who have been denied the ability to make strategic life choices acquire such an ability” has highly influenced the course of gender-responsive development interventions. In her analysis Kabeer identifies three critical components of empowerment:

- Resources: material, human, and social resources that are distributed through institutions and relationships in society

- Agency: the ability to define and act on one’s individual or shared goals. While agency tends to be operationalized as “decision-making” in the social science literature, it can take various forms. It is exercised by individuals as well as by collectives and can manifest as bargaining and negotiation, deception and manipulation, subversion, or resistance, in addition to more intangible processes such as reflection and analysis.

- Achievements: well-being outcomes

Measuring Empowerment in Agriculture

Although there is general agreement in the development arena that empowerment needs to encompass the three components specified by Kabeer (i.e., resources, agency, and achievements), the representation of an “empowered woman” and an “empowered individual” will vary across regions, groups, and time (Kabeer, 1999). Measuring empowerment in agriculture has been one of the main aims of development interventions. It is also one of the aims most contested by feminist scholars. One of the issues raised by researchers is the need to adapt measurement tools to local or inside values instead of imposing outside or oversimplistic views of empowerment (Meinzen-Dick et al., 2019).

One of the most popular instruments currently used in development to measure empowerment is the Women’s Empowerment Index in Agriculture (WEAI), which was developed and launched in February 2012 by the International Food Policy Research Institute, Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative, and the United States Agency for International Development’s (USAID) Feed the Future initiative. The WEAI is a unique tool that includes two subindices: one measures women’s empowerment across five main agricultural sectors and the other measures women’s empowerment relative to men within their households. The five main agricultural sectors are (1) decisions about agricultural production, (2) access to and decision-making power about productive resources, (3) control of the use of income, (4) leadership in the community, and (5) time allocation.

While there are considerable limitations to the use of numeric indicators to assess a person’s level of empowerment, the WEAI is intended to provide a baseline for measuring change over time (Alkire et al., 2013). Researchers suggest triangulating the information from the WEAI questionnaire with the tools in the qualitative WEAI, which is based on in-depth interviews and focus groups. This allows researchers to capture the nuances of empowerment at the local level that can be overlooked when using the standardized survey (Meinzen-Dick et al., 2019). This important instrument for analysis has been implemented across many regions of the world and shapes what we know about gender differences in agricultural production. Critics of the WEAI argue that it oversimplifies empowerment, especially for local contexts, and potentially overlooks transformative change, highlighting the need for qualitative research to provide nuance (Tavenner, 2022).

Gender and Women’s Organizations

Grassroots and local organizations are a key component of women’s and underserved communities’ development (Staggenborg, 2011). Grassroots organizations are spaces where individuals can organize at the local level to manage and access resources, influence policy, and work towards individual well-being. Of course, there is no perfect organization, and grassroots organizations can also be spaces where local hierarchies and social differentiation are present. In the long term, however, grassroots organizations have the power to transform rooted social injustices. In the next section, we present the case of an indigenous women’s grassroots association and its work to improved women’s and youth’s lives in rural Honduras.

CASE STUDY: “PROMOTING GENDER EQUITY THROUGH EMPOWERMENT: A WOMEN’S GRASSROOTS ASSOCIATION IN HONDURAS.”

Indigenous women’s groups can be spaces of resistance against structural forms of discrimination. Women’s motivations to form groups originate in the perceived difficulties of satisfying women’s strategic interests of gender or a lack of representation in other spaces. Women’s organizations can also have influence the more profound level of hidden structures that shape the distribution of power and resources within a society and reproduce them over time (Manzanera-Ruiz & Lizarraga, 2016).

One example of a women’s group is the Lenca women’s association, AMIR (Asociación de Mujeres Intibucanas Renovadas). AMIR is a grassroots, indigenous Lenca association of women that has a long history of advocating for women’s rights throughout the municipality of Intibucá in Honduras. AMIR is a platform for members to address their struggles through collective action. Through political advocacy and development projects, AMIR members work towards the intrinsic empowerment of Lenca women and their families. The association operates in more than 25 communities and has approximately 450 active members.

AMIR activities are focused on Western Honduras. Subsistence agriculture is a significant part of the livelihood of most communities in this part of the country. Honduras’s Lencas are the largest ethnic group, accounting for 63% of the country’s ethnic groups , and its population is 6% of the national total (INE, 2015). The Lencas are not only the largest ethnic group, but they are also among the poorest groups in the country. Indigenous populations living in Honduran rural areas suffer alarming levels of poverty and malnutrition, with 72% of indigenous households living in extreme poverty (CADPI, 2017) .

AMIR emerged at the beginning of the 1980s as a Lenca women’s association linked to the Catholic Church. In the beginning, most of the members’ responsibilities were tied to supporting religious activities coordinated by the church. However, when they began their empowerment process, the AMIR members realized that their interests did not match those of the church; they nevertheless continued supporting church activities. Meanwhile, AMIR continued recruiting new members and looking for opportunities, projects, and partners to contribute to their goal of educating Lenca women on issues of rights, empowerment, sustainable agriculture, food security, and agricultural product transformation. One of their first efforts focused on increasing literacy among their members.

AMIR’s origins are storied. One of the founding members walked long distances to gather more members. She had to walk for several days since roads for public transportation were not available. Despite living in a culture where women had to ask permission from their husbands to leave the house, she traveled alone. Due to the long journeys, she had to sleep in the forest or at other members’ houses to keep recruiting new members for the association.

Through its efforts, AMIR received some donated land on which its headquarters are now located. This land marked a before and after in AMIR’s relationship with the church and the communities . Because it was an organization born with the church’s support, the church requested to be handed over . This land was part of the organization’s plan to build a fruit-processing plant where AMIR members could sell their produce. AMIR decided to keep the land and sacrifice its relationship with the church. The church responded by ostracizing AMIR and its members, which negatively impacted the association’s membership.

Despite these difficulties, AMIR survived, and its members built their processing plant where they could sell their harvest. Their products are sold locally under the Siguatas Lencas brand. This short story, which exemplifies the gender barriers faced by AMIR members, provides insight into the social, cultural, and structural barriers women still face and the resistance strategies they can adapt to counteract oppressions through collective action. It also demonstrates how traditional gender roles tend to relegate women to reproductive activities, like caring for others, preparing food, and cleaning. In this example, the church relied upon and reproduced traditional gender roles to support its activities and went against AMIR when its members challenged those roles.

Conclusion

- “Sex” and “gender” have been widely used as synonyms, but they are not the same. Sex refers to biological and physiological characteristics, while gender refers to behaviors, roles, expectations, and activities within society.

- Society assigns different gender roles based on people’s sex, and those assigned roles and expectations act as barriers for women.

- WID, WED, WAD and GAD are approaches to gender that have been implemented in international development to understand differences between men and women. Many of these efforts have focused on the Global South and agriculture.

- Gendered dimensions of agriculture include differences in accessing resources, as well as disparities in responsibilities, working conditions, and experiences of food insecurity.

- The gender asset gap has been widely utilized to study differential access to assets between men and women who are engaging in agriculture.

- Empowering women and reducing gender-based inequalities are central goals of development policy. Empowerment in agriculture has three critical components: resources, agency, and achievements.

Further Exploration

To learn more about gender, agriculture, and development, consult the following resources.

Gender and Sexuality

Brasier, K. J., Sachs, C. E., Kiernan, N. E., Trauger, A., & Barbercheck, M. E. (2014). Capturing the multiple and shifting identities of farm women in the northeastern United States. Rural Sociology, 79(3), 283–309. https://doi.org/10.1111/ruso.12040

Campbell, H., & Michael, M. B. (2000). The question of rural masculinities. Rural Sociology, 65(4), 532–546. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1549-0831.2000.tb00042.x

Killermann, S. (2017). The genderbread person. hues, a global justice collective. Retrieved April 10, 2021, from https://www.genderbread.org/

Leslie, I. S. (2017). Queer farmers: Sexuality and the transition to sustainable agriculture. Rural Sociology, 82(4), 747–771. https://doi.org/10.1111/ruso.12153

Hoffelmeyer, M. (2021). Queer farmers: Sexuality on the farm. In C. E. Sachs, L. Jensen, P. Castellanos, & K. Sexsmith (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Gender and Agriculture (pp. 348–359). Routledge.

Gender Transformative Approaches (and the Decolonial Question)

Wong, F., Vos, A., Pyburn, R., & Newton, J. (2019). Implementing gender transformative approaches in agriculture. In A discussion paper for the European Commission.

Lugones, M. (2010). Toward a decolonial feminism. Hypatia, 25(4), 742–759. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40928654

The Gender Asset Gap

Quisumbing, A., Meinzen-Dick, R., Njuki, J., Johnson, N., Wathanji, E., & Rubin, D. (2012). A toolkit on collecting gender & assets data in qualitative & quantitative program evaluations. GAAP: Gender, Agriculture, & Assets Project of the International Food Policy Research Institute and International Livestock Research Institute. https://www.ifpri.org/publication/gaap-gender-and-assets-toolkit

Women’s Empowerment

Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (WEAI) Resource Center

Development Organizations working on Gender Transformative Approaches

Check Your Knowledge!

- How would you explain to a friend the differences between sex and gender?

- Are the WID, WED, and GAD approaches different? If so, in what ways?

- Why are gender transformative approaches so different from previous approaches?

- What is the relevance of gender to agriculture?

- Why do assets matter for achieving development goals?

- What are the main components of empowerment?

Synthesis Questions

- After reading this chapter, how do you think development interventions can be used to support women’s empowerment in non-invasive and helpful ways? Is it even possible?

- Do you think it is fair to expect that once women have better access to assets, they will (or should have to) improve their households and communities’ agricultural productivity and nutritional status?

- How do you think the subjects discussed in this chapter relate to other social phenomena such as climate change, migration, and generational farming?

Author Notes

Hazel Velasco Palacios and Alfredo Reyes, Rural Sociology and International Agriculture and Development, Department of Agricultural Economics, Sociology, and Education Pennsylvania State University

Paige Castellanos, Oxfam America

We have no conflicts of interests to disclose. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Hazel Velasco, 308 Armbsy University Park, State College, PA 16803. Email: hgv5008@psu.edu

References

Agarwal, B. (1988). Who sows? Who reaps? Women and land rights in India. Journal of Peasant Studies, 15(4), 531–581. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066158808438377

Agarwal, B. (2018). Gender equality, food security and the Sustainable Development Goals. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 34, 26–32.

Alkire, S., Meinzen-Dick, R., Peterman, A., Quisumbing, A., Seymour, G., & Vaz, A. (2013). The Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index. World Development, 52, 71–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.06.007

Allen, P., & Sachs, C. (2007). Women and food chains: The gendered politics of food. International Journal of Sociology of Food and Agriculture, 15(1), 1–23.

Bebbington, A. (1999). Capitals and capabilities: A framework for analyzing peasant viability, rural livelihoods and poverty. World Development, 27(12), 2021–2044.

Boserup, E. (1970). Male and female farming systems. In Woman’s Role in Economic Development (pp. 15–35). Please add editors and publication information for full book

Brasier, K. J., Sachs, C. E., Kiernan, N. E., Trauger, A., & Barbercheck, M. E. (2014). Capturing the multiple and shifting identities of farm women in the northeastern United States. Rural Sociology, 79(3), 283–309. https://doi.org/10.1111/ruso.12040

CARE Evaluations. (2022). Food security and gender equality: A synergistic understudied symphony. https://www.careevaluations.org/evaluation/food-security-and-gender-equality/

Centro para la Autonomía y Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas. (2017). Nota ténica de país sobre cuestones de los pueblos indígenas: República de Honduras.

Chowdhury, E. H. (2015). Development. In L. Disch & M. Hawkesworth (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of feminist theory (Vol. 1, pp. 1–23). Please add publication info for full book https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199328581.013.8

Coles, C., & Mitchell, J. (2010). Gender and agricultural value chains and practice and their policy implications: A review of current knowledge and practice and their policy implications [FAO Agricultural Development Economics Working Paper 11–05].

Deere, C. D., & Doss, C. R. (2006). The gender asset gap: What do we know and why does it matter? Feminist Economics, 12(1–2), 1–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545700500508056

Food and Agriculture Organization. (2010). Gender and land rights database. United Nations. Accessed April 14, 2021, at http://www.fao.org/gender-landrights-database/data-map/statistics/en/

Food and Agriculture Organization. (2011). The state of food and agriculture. United Nations. https://www.fao.org/3/i2050e/i2050e.pdf

Food and Agriculture Organization. (2018). Developing gender-sensitive value chains. United Nations. http://www.fao.org/3/i9212en/I9212EN.pdf

Food and Agriculture Organization. (2023). The status of women in agrifood systems. United Nations. https://doi.org/10.4060/cc5343en

Garrity-Bond, C. (2018). Ecofeminist epistemology in Vandana Shiva’s The Feminine Principle of Prakriti and Ivone Gebara’s Trinitarian Cosmology. Feminist Theology, 26(2), 185–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/0966735017738660

Hoffelmeyer, M. (2021). “Out” on the farm: Queer farmers maneuvering heterosexism & visibility. Rural Sociology, 86(4), 752–776. https://doi.org/10.1111/ruso.12378

INE. (2015). Encuesta Permanente de Hogares de Propositos Multiples. https://www.ine.gob.hn/V3/imag-doc/2020/01/Acta-de-Aprobación-Metodología-de-la-Medición-de-la-Pobreza-Monetaria_30-de-enero.pdf

Johnson, N. L., Kovarik, C., Meinzen-Dick, R., Njuki, J., & Quisumbing, A. (2016). Gender, assets, and agricultural development: Lessons from eight projects. World Development, 83, 295–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.01.009

Kabeer, N. (1999). Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Development and Change, 30(May), 435–464.

Kawarazuka, N., Doss, C., Farnworth, C. R., & Pyburn, R. (2022). Myths around the feminization of agriculture: Implications for global food security. Global Food Security, 33(June). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2022.100611

Killermann, S. (2017). The genderbread person. Retrieved April 10, 2021, from https://www.genderbread.org/

Leach, M. (2007). Earth mother myths and other ecofeminist fables: How a strategic notion rose and fell. Development and Change, 38(1), 67–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444306675.ch4

Leslie, I. S. (2017). Queer farmers: Sexuality and the transition to sustainable agriculture. Rural Sociology, 82(4), 747–771. https://doi.org/10.1111/ruso.12153

Manzanera-Ruiz, R., & Lizarraga, C. (2016). Motivations and effectiveness of women’s groups for tomato production in Soni, Tanzania. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 17(1), 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2015.1076773

Meinzen-Dick, R., Johnson, N., Quisumbing, A. R., Njuki, J., Behrman, J. A., Rubin, D., … Waithanji, E. (2014). The gender asset gap and its implications for agricultural and rural development. In Gender in agriculture: Closing the knowledge gap, 91–116. Please add editor and publisher info https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8616-4_5

Meinzen-Dick, R., Rubin, D., Marlène, E., Abenakyo Mulema, A., & Myers, E. (2019). Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture: Lessons from Qualitative Research. Please add publisher info

Mohanty, C. T. (1984). Under Western eyes: Feminist scholarship and colonial discourses. Boundary, 2(3), 333–358.

Nightingale, A. (2006). The nature of gender: Work, gender, and environment. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 24(2), 165–185. https://doi.org/10.1068/d01k

Oxfam America. (2020). Time to care: unpaid and underpaid carework and the global inequality crisis. https://www.oxfamamerica.org/explore/research-publications/time-care/

Quisumbing, Agnes., Meinzen-Dick, R., Raney, T. L., Croppenstedt, A., Behrman, J. A., & Peterman, A. (2014). Gender in agriculture: Closing the knowledge gap. In Gender in agriculture. Please add editor and publisher info https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8616-4

Quisumbing, A., Meinzen-Dick, R., Njuki, J., Johnson, N., Wathanji, E., & Rubin, D. (2012). A toolkit on collecting gender & assets data in qualitative & quantitative program evaluations. GAAP: Gender, Agriculture, & Assets Project of the International Food Policy Research Institute and International Livestock Research Institute. https://www.ifpri.org/publication/gaap-gender-and-assets-toolkit

Quisumbing, A. (1996). Male-female differences in agricultural productivity: Methodological issues and empirical evidence. World Development, 24(10), 1579–1595. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(96)00059-9

Quisumbing, A., Rubin, D., Manfre, C., Waithanji, E., van den Bold, M., Olney, D., & Meinzen-Dick, R. S. (2014). Closing the gender asset gap: Learning from value chain development in Africa and Asia. SSRN Electronic Journal, (February). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2405716

Quisumbing, A., & Maluccio, J. (2003). Resources at marriage and intrahousehold allocation: Evidence from Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Indonesia, and South Africa. Oxford Bullentin of Economics and Statistics, 65(3), 288–327.

Rathgeber, E. M. (1990). WID, WAD, GAD: Trends in research and practice. Journal of Developing Areas, 24(4), 489–502.

Sachs, C. E. (1996). Gendered fields: Rural women, agriculture, and rnvironment. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429493805

Sachs, C. E. (2014). Gender, race, ethnicity and sexuality in rural America. In C. Bailey, L. Jensen, & E. Ransom (Eds.), Rural America in a globalizing world (pp. 421–434). West Virginia University Press.

Sachs, C. E., Barbercheck, M., Braiser, K., Kiernan, N.E., & Terman, A.R. (2016). The rise of women farmers and sustainable agriculture. Please add publisher info

Shiva, V. (1989). Development, ecology, and women. In Staying Alive: Women, Ecology and Survival in India (pp. 658–666). Please add editor and full book publisher info https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429499142-99

Staggenborg, S. (2011). Social movements. https://doi.org/211 Check link?

Tavenner, K., Crane, T.A. (2022). Hitting the target and missing the point? On the risks of measuring women’s empowerment in agricultural development. Agriculture and Human Values, 39, 849–857. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-021-10290-2

Trauger, A., Sachs, C., Barbercheck, M., Brasier, K., & Kiernan, N. E. (2010). “Our market is our community”: Women farmers and civic agriculture in Pennsylvania, USA. Agriculture and Human Values, 27(1), 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-008-9190-5

Wong, F., Vos, A., Pyburn, R., & Newton, J. (2019). Implementing gender transformative approaches in agriculture. In A discussion paper for the European Commission. Please add additional info

Ynalvez, M. A., & Shrum, W. M. (2015). Science and development. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (pp. 150–155). Please add editor and publisher info https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.85020-5