15 Global Agricultural Extension

Tyler McFeaters and Elisa Lauritzen

Learning Objectives

The goal of this chapter is to introduce students to agricultural extension, which is both a worldwide effort to create an awareness of agriculture and a system within which individuals can acquire knowledge and skills to improve their quality of life. We know we will have achieved this goal when students can:

- Define agricultural extension in the context of international agricultural development.

- Compare and contrast agricultural extension in two or more countries based on the case studies presented in this chapter.

- Critically assess how the four paradigms of agricultural extension contribute to agricultural systems across the globe.

- Successfully identify and use resources available through local agricultural extension systems to research a topic that is important to the students or their community

.

Definitions

Agricultural extension: Agricultural advisors and services including nonformal education.

Private extension: Fee-based agricultural advisors or services.

Nongovernmental organization (NGO): Nonprofit entity that works independently of governments but may receive government funds (Gibson, 2013).

Nonprofit organization: An organization that functions as a business but donates or utilizes any profit for public or social benefit (Gibson, 2013).

Extension program: A set of orchestrated educational experiences purposefully selected to address a locally identified need or issue of broad public concern (Rennekamp, 1995).

Top-down extension: Paternalistic system of extension in which there is a one-way flow of information from extension workers to farmers.

Bottom-up extension: Participatory system of extension in which there is a two-way exchange of information.

Farmer field school: Community-based, nonformal education that consists of intensive, season-long programs where groups of 20–25 farmers meet regularly to learn and experiment on a given topic (Braun et al., 2000; Davis, 2006).

Needs assessment: A systematic set of procedures that are used to determine needs, examine their nature and causes, and set priorities for future action (Witkin et al., 1995).

Delivery method: Techniques used in extension programs to promote effective learning, reinforce the learner, and integrate new information (Radhakrishna, 2020).

Introduction

Agricultural production takes place all around the globe (even in Antarctica as you can see here!). Globally, nearly one of every three employed people works in agriculture. Agricultural extension works with farmers, farmworkers, businesses, and governments all over the world to share information and optimize agricultural systems to improve lives.

Credits: Hanno Müller, AWI

What Is Agricultural Extension?

Agricultural extension is the term used around the world to describe agricultural advisory services provided to farmers. The term “extension” originally was used to describe the dissemination of formal information from research institutions like universities to communities and farmers. Modern agricultural or rural extension still relies on research institutions to facilitate research and programming. Extension can be described as nonformal education that uses programs to meet the needs of a community. It is the bridge between research and the public, and at its core, it is the sharing of research-based information to those who can use it.

- “It’s a people’s business”

- More than farming; many aspects of food security including nutrition, food science, and many other types of subject matter

- Nonformal vs. informal vs. formal education

- Education for immediate application

- Helping people help themselves

- A two-way flow of information

- Extension is the catalyst of knowledge, attitude, skills, and behavior change

Types of Extension

Agriculture extension services are provided by public, private, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). Public agencies are funded by the government. For example, in the United States, the Cooperative Extension System includes the federal government alongside the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, state extension systems, and local county and city governments where extension offices are located. Large agricultural input supplier corporations (e.g., Bayer, Corteva, Syngenta) provide agricultural advice to farmers who buy their products. When for-profit companies provide an extension service at a cost, it is considered a private extension. However, organizations like NGOs and nonprofits do not receive payment for extension services. NGOs often receive government funding but are not directly government-supported. In contrast, nonprofits are supported by donors or endowments. The type of extension system used varies from country to country and even from region to region within a country. If a country utilizes both public and private extension, the extension system is considered a pluralistic system.

Case Study: Three Types of Extension in Nepal

Agricultural extension in Nepal is pluralistic with government, international agencies collaborating with research institutions, and private companies each contributing to extension services for farmers. The Ministry of Agriculture and Development provides trainings for new farming techniques and products to improve yields (Figure 1). International agencies, like USAID and iDE in Nepal, partner with universities to conduct research to increase agricultural productivity (Figure 2). Finally, private extension is new and emerging as a way for farmers to reach out to professionals for advice.

- Farmers preparing a field for potato planting in Kavre, Nepal. Photo credit: R. C. Neupane.

- Vegetable pest management field trial in AFU, Rampur, as part of the Asia Innovative Farmers Activity Project funded by USAID. Photo credit: R. C. Neupane.

- An example of a private extension meeting during which growers learn about the use of biocontrols in pest management. Photo credit: R. C. Neupane.

History

Early Predecessors of Agricultural Extension

Information sharing in agriculture has taken place for a long time. Using clay tablets, farmers in Mesopotamia shared information with each other about how best to water crops (Jones & Garforth, n.d.). Egyptian hieroglyphs listed advice for farmers on managing crop loss during times that the Nile River would flood. Ancient Greeks would gather together on April 25 each year for Robigalia, a festival to pray and make sacrifices to the god Robigus for a good crop and to share crop information with one another. As civilization advanced and began keeping written records, agricultural information spread and helped promote agricultural practices that would generate revenue for landowners. Surviving Latin and Chinese texts indicate that land management techniques were among the information shared (Jones & Garforth, n.d.). The sharing of information, especially crop and agricultural information, facilitated empire building, boundary expansion, and exploration.

To learn more about when and where ancient peoples started farming, read “Where Did Agriculture Begin? Oh Boy, It’s Complicated” (2016) published by NPR.

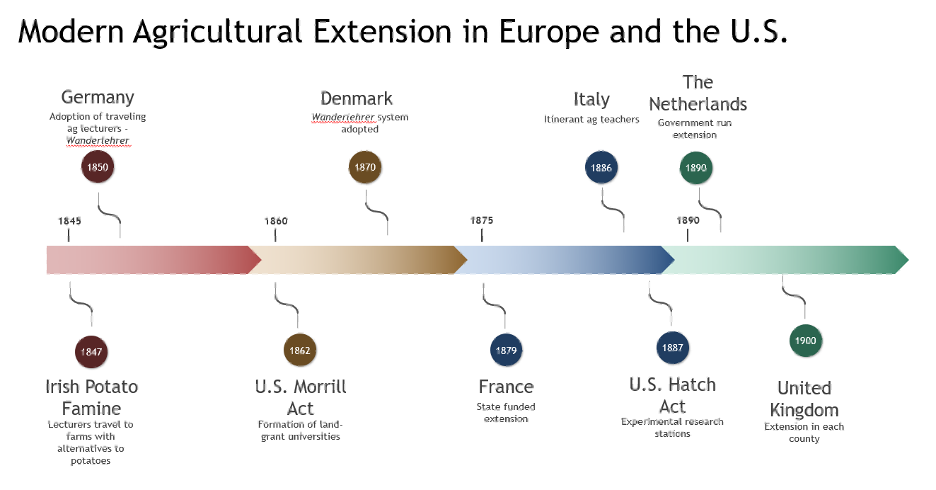

The Rise of Modern Agricultural Extension

Our modern agricultural extension organizations have strong roots in Europe and like most things, originated in a time of crisis. During the infamous Irish Potato Famine (1845–1852) and in response to the failed potato crops, government officials instructed that lecturers travel from farm to farm to share information on how to grow root crops other than potatoes. The lecturers were funded by landowners and charitable donations with some funds coming from the government (Jones & Garforth, n.d.). The program lasted for four years. Formalized extension was not adopted in the United Kingdom or Ireland for another 50 years.

This system was quickly adopted by other regions in the world. In the 1850s, in what is now called Germany, farm advisors called Wanderlehrerer (itinerant teachers) appointed by agricultural societies regularly traveled throughout the region disseminating agricultural information. Wanderlehrerer spent their summers traveling from farm to farm giving talks, demonstrating new techniques, and advising farmers. During the cooler months, Wanderlehrerer opened agricultural schools for farmers’ children. The Wanderlehrerer system spread throughout Europe and was often funded by public donations, churches, or banks. In 1879, France became the first country to adopt a government-funded agricultural extension system. This system and was overseen by the Ministry of Agriculture (Jones & Garforth, n.d.). The United Kingdom developed a similar system, but control was in the hands of local governments. These county- or borough-based systems either employed an agricultural advisor or more commonly sponsored agricultural lecturers through the university system. The subsequent reliance on university resources to meet the needs of agricultural systems led to the creation of new agricultural departments within universities and the development of agricultural schools of higher learning (e.g., Harper Adams University, Myerscough College, Banger University).

Colonialism

European extension work and agricultural education had far-reaching effects on regions around the world that had been held as European colonies. Often colonies were held as a means of sustaining agricultural resources. Extension systems among European colonies were generally focused on commodity-based agriculture and were government-run via departments of agriculture.

Case Study: Sub-Saharan Africa Extension

During the early 1900s many Sub-Saharan African countries were colonies of Great Britain, France, or other European countries. Governmental departments or ministries of agriculture were primarily responsible for “top-down” extension activities. Extension directives were dictated to farmers and enforced by local government officials like village chiefs. These extension directives were focused on technology transfer. Once many countries gained their independence during the mid-1900s, demonstration farms and other participatory methods came to be used. Separate extension systems for black and white farmers were established, with new technologies primarily available to white colonial farmers. This racial divide still impacts Zimbabwe today, although the government has tried to redistribute land more evenly. Kenya also has a pluralistic extension system, with public extension supporting smallholder farmers and larger commercial growers benefiting from private extension. More recent advances, like those in Uganda, have shifted from the traditional “top-down” approach to more “bottom-up,” farmer-driven extension services.

Mukembo, S. C., & Edwards, M. C. (2015). Agricultural extension in Sub-Saharan Africa during and after its colonial era: The case of Zimbabwe, Uganda, and Kenya. Journal of International Agricultural and Extension Education, 22(3), 50-68.

U.S. Land-Grant Institutions

In 1862, the United States passed the Morrill Act, which gave each state land with which to start a university. These schools were meant to further practical and vocational education at the college level. In 1887, the Hatch Act was passed, giving states funds to establish agricultural experiment stations for applied research. Finally, the Smith-Lever Act of 1914 laid the framework for the cooperative extension system. The job of the extension system was to relay information from academia to the public in subjects like agriculture, home economics, and energy. These acts led to the modern public cooperative extension system still seen in the United States today.

During the 1900s the focus of extension shifted to different topics as farmer and community needs changed. Around World War I, extension was focused around increasing wheat productivity, addressing labor shortages, and the production and marketing of perishable foods. During the Great Depression years, the needs shifted to farm management, the organization of farm cooperatives, and home economics. During World War II, there was a need to increase production to support the war. In the 1950s and beyond, the focus shifted to new technology adoption. Today, extension is in every state of the United States and continues to adapt to the changing needs of farmers, as well as those of urban and suburban communities, in areas like youth development, natural resources, animal systems, energy and business, home economics, food quality and safety, and horticulture.

Find a U.S. land-grant university by visiting the National Institute of Food and Agriculture’s partner directory.

Four Paradigms

Agricultural extension is built on a set of beliefs, or paradigms, that serve as pillars of its purpose and mission. There are many influences on extension paradigms, including governments, global challenges, and local needs. These paradigms work together to describe how and why communication within extension takes place. The four paradigms of agricultural extension are

- technology transfer;

- advisory work;

- human resource development; and

- facilitation for empowerment.

How communication takes place is usually described as either paternalistic or participatory. Paternalistic communication models in extension involve the extension agent or representative and the farmers in a teacher–student relationship. This type of communication is also called a top-down system. Participatory communication models involve the same actors; however, information is reciprocally shared and learned between the farmer and the extension agent. This is often referred to as a bottom-up system of information sharing.

Information dissemination through extension systems can be defined as persuasive or educational. This helps us understand why we communicate through extension systems. Persuasive communication within extension looks to change behavior, while educational communication works to improve knowledge. This understanding, coupled with the four paradigms, is a robust way of defining agricultural extension services. As agricultural extension continues to develop across the globe, paradigms may change or expand. It has been suggested that a fifth paradigm, globally driven markets, be included as a driving factor in the development of extension systems (Food and Agriculture Organization, 2001). Proponents of this new paradigm argue that by including a global market aspect and a focus on commodity-based agriculture to meet market demands, agricultural extension “will become more purpose-specific, target-specific, and need specific” (FAO, 2001).

Case Study: Cacao and Coffee in Colombia

Have you ever wondered what a piece of chocolate and a good cup of coffee have in common?

Other than being delicious treats, these products come from tropical countries such as Colombia. Colombia, the fifth largest and the third most populous country in Latin America, has long been a major producer of coffee and cacao, the source of chocolate. Most of the nation’s coffee and cacao are grown in the Andes Mountains (Image 1). While it is common to find coffee in full sun, cacao trees usually grow under the shade of tropical trees (Image 2).

Cacao and coffee are crops that provide livelihood opportunities to more than one million smallholder farmers. Thus, agricultural extension efforts providing the information needed by farmers remain a core strategy to spur economic growth among small farmers.

Two key institutions supporting farmers are the national associations for cacao and coffee producers: Fedecacao and Fedecafe, respectively. To represent coffee and cacao growers’ interests, these organizations engage in the following activities:

- Offer Colombian farmers a purchase guarantee.

- Generate technology through their research centers.

- Develop rural extension through educational processes.

- Position Colombian coffee and cacao in the national and international markets. For instance, in the case of coffee, the well-known Juan Valdez character (Image 3) distinguishes 100% Colombian coffee from coffee blended with beans from other countries.

Topics Addressed and Services Provided

Across the globe, there are thousands of organizations that work in agricultural extension. Most organizations do not focus on one topic only but instead provide aid to farmers and communities in several areas. For example, some of the largest agricultural development organizations, like Oxfam and CARE, provide extension services related to nearly all the topics listed below. These topics range from technical agriculture practices to youth development, gender equity, and beyond. Here we highlight some of the major topics addressed in extension around the globe, though certainly there are many others depending on the needs of local communities.

Agri-food Systems and Genetics

As our food systems become increasingly global, agricultural extension works to meet the needs of local, regional, and global communities. Agri-food systems include all aspects of the production, processing, distribution, and consumption of food and fiber (Fine, 1998). Many organizations offer extension services to assist with agri-food systems. The International Food Policy Research Institute is one such organization. Its agricultural extension programs work to increase agricultural productivity in rural areas by teaching growers about the management of pests and diseases, improved genetics, and the sustainable management of soil and water resources.

There is an increased need for improved crop and animal genetics in agriculture to meet the nutritional needs of a growing world population. One of the best-known examples of genetic improvement is that of Norman Borlaug and his work to improve wheat varieties by selectively breeding for high-yielding, disease-resistant wheat varieties. His work was facilitated through an extension-oriented research organization known as the Centro Internacional de Mejoramiento de Maíz y Trigo whose primary focus is the genetic improvement of seeds.

Climate Change

Climate change impacts agriculture and requires growers to adapt to changing environments. Agricultural extension is a key player in initiating programs to help mitigate these impacts by disseminating research-based information, technologies, and policies and problem-solving with farmers, governments, and other organizations on a global scale. Global agricultural extension systems work together to find meaningful ways to share information with farmers that is intended to reduce the impact of climate change on their systems. There are countless organizations whose focus is on climate change’s effects on agricultural systems. They include the Climate Action Network, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, and Environmental Defense Fund.

Gender Equity

Addressing gender inequities in agricultural systems, including within the agricultural extension system itself, has become a critical focus for many organizations. According to the United States Agency for International Development (USAID, 2015), women make up about 43% of the global agricultural labor force. Women farmers face challenges in accessing resources like land, technology, education, and credit. Some projections indicate that if women had equal access to these resources, global yields would increase and nutritional deficiencies would be reduced (USAID). Agricultural extension works to improve women’s access to these resources through efforts like farmer field schools, fellowship programs, and credit programs. Many of the programs recognize the time constraints of childcare and domestic responsibilities and offer support in these areas as well. In addition, agricultural extension systems recognize that women are often subject to abuse and trauma and have responded by creating programs and safe places for women to recover and acquire life skills that may be transferable to the workforce.

Youth Development

In the United States, 4-H is the extension organization for youth development. 4-H is a program primarily run by volunteers that gives youth equal opportunities to learn valuable knowledge and develop lifelong skills. 4-H program areas range from STEM and agriculture to healthy living and civic engagement. Agricultural extension programs also work with youth in urban settings to foster a better understanding of agricultural systems.

Youth programs outside of the United States often generate interest in agriculture among young people who may otherwise overlook the field for more lucrative options. These programs look to support and strengthen youth involvement in agriculture and extension by exhibiting the breadth of agriculture including technology, research opportunities, and well-compensated careers. Feed the Future’s Developing Local Extension Capacity project address the challenges of youth participation in agriculture in the Global South through partnerships with larger global programs like the International Food Policy Research Institute.

Food Security and Nutrition

Food security is a major issue in almost every country but especially in developing nations. Public extension and NGOs across the globe dedicate a lot of effort to reducing hunger. One of the largest food security organizations is the World Food Programme of the United Nations. This organization works to combat hunger by providing food assistance in emergencies and helps communities “to improve nutrition and build resilience.” Many faith-based organizations such as World Vision offer similar programs. “Sponsor a Child” programs provide consistent food resources to those in need. These programs take a holistic approach by providing medicine, education, disaster relief, and clean water.

Natural Resources Management and Biodiversity Conservation

Natural resource management and environmental conservation are important topics in extension, especially in countries with issues like deforestation, land degradation, and water pollution. One organization that seeks to combat these issues is the International Institute for Environment and Development. The institute is active in more than 60 countries and its goal is to conduct research that promotes sustainable development, environmental protection, and the identification of local solutions. An example of public extension in biodiversity conservation is the ABC Plan developed by Brazil’s Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Supply. The ministry helps with extension activities like advertising campaigns, technology transfer, technical troubleshooting, the training of technicians and rural producers, research, and rural credit in order to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, improve soil health, and reduce deforestation.

Sustainable Development Goals

The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) overlap with the mission of many agricultural extension organizations. Nearly all of the 17 goals are within the bounds of agricultural extension. Many countries have international economic development organizations that collaborate to provide resources and services in thematic areas that align with the SDGs. USAID, Japan International Cooperation Agency, and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency are several examples of publicly funded international relief agencies.

Forestry

Forestry is an important topic for extension agents in many countries. For example, in the United States, the American chestnut, walnut, and elm trees have each been plagued with devastating pathogens that have led to disease epidemics. American chestnut blight, caused by the fungus Cryphonectria parasitica, thousand cankers disease in black walnut trees, and Dutch elm disease and elm yellows in elms need to be treated to prevent these species from dying. Currently research is being done to develop blight-resistant chestnuts to introduce into U.S. forests. Extension efforts like that of the American Chestnut Foundation are educating people about efforts to reestablish the chestnut tree in U.S. ecosystems. Beyond combatting up-and-coming pathogens, implementing sustainable forest management practices is critical to maintaining a healthy forest ecosystem.

Agroforestry example in Zambia- Raymond B.

Peace Corps volunteers support local Zambian Forestry Department officers to conserve forest areas, reforest, incentivize soil conservation practices, and build capacity towards income-generating activities that do not involve depleting forest resources. These projects are often indirect ways to conserve forest resources. For example, Raymond Balaguer, a recent Peace Corps volunteer, learned modern beekeeping techniques and introduced the Kenyan top-bar hive to the local community as a means of encouraging forest preservation. Bees require a regular pollen food source to thrive. Raymond and his colleagues found that when beekeepers learned that bees collect pollen from different tree species throughout the year, community members responded by reducing the number of trees they removed from the forest to ensure the bees were cared for. Four farmers saw the process from beginning (making the hive) to end (selling the honey) and were already benefitting from their bees. They understood that most of the honey in the area came from tree flowers and saw the value of slowing down the cutting of trees. They also partnered with Conservation Farming Unit representatives to incentivize using different tilling equipment to conserve soil structure in maize, soybean, sunflower, cotton, and peanut fields. Additionally, a project of budding and grafting agroforestry trees and fruit trees was carried out, and more than 250 trees were planted over a span of nine months.

Policy and Rural Economic Development (Trade and Value Chains)

Extension organizations that impact policy, provide economic support, and improve food chains for certain commodities work in this thematic area. One example is a nonprofit organization called the World Cocoa Foundation. World Cocoa Foundation members are cocoa and chocolate manufacturers, processors, supply chain managers, and companies throughout the world. The organization’s goal is to help farmers and communities in the cocoa sector grow cocoa sustainably with a focus on profitability, the protection of human rights, and resource conservation. Many other NGOs provide microfinancing to people and communities in need.

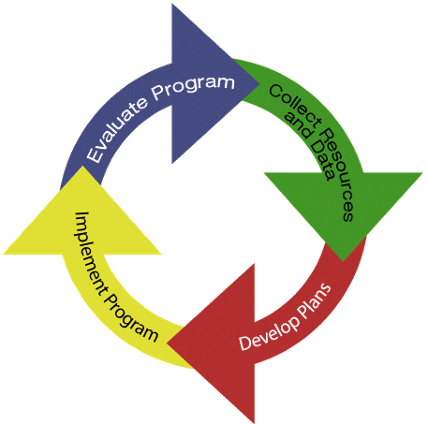

Extension Programs

A fundamental part of agricultural extension services is providing extension programs. Programs are a set of educational activities with objectives and outcomes that meet a need or help facilitate a desired behavior change. Many different program development approaches are used to guide program design. Each approach includes inputs, outputs, and outcomes to show how a program will bring about change. Inputs include the resources needed to conduct a program. Outputs are the actions or activities with which participants engage. Outcomes are the results of a program, which may be knowledge gain, attitude change, or skills learned. Program design is based on three steps that are included in every program design model: planning, implementation, and evaluation.

Program Design: Planning

The first stage is planning. There are many factors that need to be considered when designing a program. Participants in the program may have a variety of social, historic, economic, educational, emotional, and personal/political factors that impact whether a program will be successful. Planning a program consists of doing a needs assessment, determining program priorities and the target audience, and writing project goals and objectives. The needs assessment identifies gaps between the existing and desired conditions. When planning a program, it is important to prioritize the needs of the local community.

Once the needs and target audience have been determined, specific objectives can be written. Objectives are brief, clear statements that describe knowledge, skills, and attitudes that reflect the broader goals or purposes of a project. Program objectives should be specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and trackable (SMART). SMART objectives capture the nature of the program, the audience, the intended outcomes, and the measures by which a program will be evaluated. Finally, the program delivery methods that best meet people’s needs must be identified.

Program Delivery: Implementation

Program implementation or delivery methods are meant to promote learning by providing experiential opportunities for learners. Methods should help reinforce participants’ learning and help participants integrate new knowledge with their prior knowledge and skills. Delivery methods may be designed for individual, group, or mass audiences. Communication with the audience may be conducted in writing via online articles or fact sheets, verbally via meetings or radio advertisements, or visually through demonstrations, videos, or other techniques. The type of delivery method used depends on the objectives. Objectives may be to give information, teach skills, or help the audience apply their knowledge. For information giving, lectures, question-and-answer sessions, and other methods are appropriate. Workshops and demonstrations are the best methods to promote skill acquisition. Problem solving and knowledge application are best facilitated by case studies, group discussions, and workshops. The chart below provides a fuller list of delivery methods used in extension programming. The effectiveness of delivery methods depends on many factors, but the internet and social media have increased the reach of extension programs in recent years.

| Individual | Group | Mass |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Program Evaluation

Program evaluation is used during and after an extension program is completed to assess the success of the program. Collecting information about the program shows whether the program objectives were reached. Ongoing and summary surveys of program participants help to guide the program design and improve it for the future. Surveys may ask participants how they liked a program, how likely they are to adopt new practices or behaviors, or about other aspects of the content of the program. Skills and knowledge can be tested via examinations and practical evaluations. Evaluations may occur in the short-term (immediately following a program), intermediate term (days to weeks after a program), or long term (six months to a year following a program). The evaluation of the impact of a program is based on the increase in knowledge and behavior change of participants and the achievement of the objectives of the program.

Information Communication Technology

In 2017 approximately 49% of the world’s population had access to the internet (World Bank, 2017). The percentage is significantly lower (around 21%) in developing countries. There are clear benefits to using the internet as a tool for agricultural extension. Use of online extension services and information can help farmers by providing them with opportunities to access affordable credit, look for good market prices, and obtain up-to-date technical crop and livestock information (Food and Agriculture Organization, 2017). Overall, information communication technology (ICT) can drive behavior change that helps farmers produce more and better manage their farms.

ICT has the potential to increase the reach of traditional extension programming. Its potential uses include but are not limited to determining farmers’ needs, providing information to help farmers meet those needs, and evaluating innovations and extension programs. A variety of ICTs may be used including radio, television, video, mobile phones, smart devices, and computers with internet access. Each platform has pros and cons depending on the goal of the extension activities. For raising awareness of issues and providing information, radio, video, and websites may be most appropriate (Bell, 2015). Interactive activities can be conducted via mobile phones or other smart devices. Webinars and video conference calls have been used in extension to conduct meetings remotely. ICTs may be used to provide farmers access to markets and commodity prices. Extension-program participants with access to the internet can help evaluate the success of the programs using a mobile phone or other device.

Some countries have already implemented ICTs in their extension programs. These countries include the United States, Afghanistan, Peru, and Ukraine. Many countries have begun using websites to post technical articles and fact sheets. Another example of international collaboration on extension resources is the Inter-American Institute for Cooperation. This organization provides growers with online resources like publications, courses, articles, the contact information of specialists, and news updates. The organization addresses a variety of issues related to production, food quality and safety, climate change, international trade, and rural development. Online websites and databases provide virtually limitless knowledge and advice to growers who have access to the internet.

Overall, there is a promising future for ICTs in agriculture extension as more and more growers gain access to the internet through computers and other smart devices. However, these resources cannot completely replace traditional extension delivery methods. As extension programming shifts to virtual platforms, poor, rural farmers with no access to these platforms will be left behind. ICTs must continue to supplement, rather than replace, participatory delivery methods.

Limitations

While agricultural extension has many benefits, there are some limitations and issues. The first barrier to extension’s success is inconsistent funding. Developing countries that have public extension systems suffer from insufficient funding that limits their ability to hire qualified extension agents. Transitions in political leadership often lead to changes in agricultural budgets. A lack of support and commitment from governments negatively impacts extension success (Anderson & Feder, 2004). Furthermore, because agricultural extension systems are no-cost services, recapturing costs is often not possible until much later.

The second hindrance to agriculture extension is the diffusion of innovations. Farmers or community members may be inherently inclined to adopt new practices or they may be more hesitant to change. People who have always worked or lived a certain way tend to follow the traditions set by their parents and model whatever is most popular in the local culture. Extension involves taking farmers’ precious time to teach them about new technologies or more sustainable management strategies. However, it is not the most efficient use of their time and the impact of the innovation being proposed may not be considered sufficiently motivating.

The final limitation addressed here is the magnitude of the role that agricultural extension will need to play in order to meet the challenge of global food security and sustainability. Feder et al. (1999) described these challenges as the “scale and complexity of the extension task” (p. 7). At the start of the new millennium, there were approximately 800,000 extension agents globally working to meet the needs of 1,200 million patrons (Feder et al., 1999). The scale of this disparity has likely grown over the last 20 years as funding for these programs has become harder to secure. The complexity of the issue revolves around the many sources of information that are available to farmers, the diversity and aims of the organizations involved, and the various missions of agricultural extension. In short, there are currently not enough people involved in agricultural extension for extension to meet the needs of its patrons.

Conclusion

Agricultural extension exists worldwide and entails the dissemination of new knowledge and ideas for the purpose of improving farms, families, and communities. It is a crucial component of the global agricultural system that aims to support farmers, improve technologies, and meet the needs of its patrons. Agricultural extension programs work with farmers, organizations, and governments to meet the growing global demand for agricultural products.

The four paradigms—technology transfer, advisory work, human resource development,

and facilitation for empowerment—together define the mission and purpose of agricultural extension. Many organizations are involved in extension work and offer services that focus on areas such as food security, gender equity, and climate change via myriad programs that are carefully and intentionally developed. Agricultural extension is a people’s business, and its purpose is the sharing of knowledge and information to improve the lives of those it serves.

Further Exploration

Penn State Extension Youtube Channel

Check Your Knowledge

- What is the definition of agricultural extension?

- What is the difference between paternalistic and participatory systems of extension?

- What are three topic areas that global extension covers?

- What are the three steps to program design?

Synthesis Questions

- How do the four paradigms of extension differ in the United States and Nepal? How are they similar?

- How do ICTs contribute to agricultural extension? What are some of the challenges in utilizing ICTs?

- Based on your reading of the case studies in this chapter, which international extension system do you think is the most effective and why?

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Rama Radhakrishna, Dr. Stephen Mukembo, Alejandro Gil Aguirre, Ram Chandra Neupane, and Raymond Balaguer for their time, expertise, and willingness to share their experiences. Their contributions to this chapter are appreciated.

References

Anderson, J. R., & Feder, G. (2004). Agricultural extension: Good intentions and hard realities. World Bank Research Observer, 19, 41–60.

Bell, M. (2015). ICT–Powering behavior change in agricultural extension. Feed the Future. United States Agency for International Development (USAID). https://meas.illinois.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Bell-2015-ICT-Powering-Behavior-Change-in-Ag-Ext-MEAS-Brief.pdf

Braun, A. R., Thiele, G., & Fernández, M. (2000). Farmer field schools and local agricultural research committees: Complementary platforms for integrated decision-making in sustainable agriculture. Overseas Development Institute.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Roadmap for state program planning. Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/programs/spha/roadmap/

Davis, K. (2006). Farmer field schools: A boon or bust for extension in Africa? Association for International Agriculture and Extension Education, 13(1).

Feder, G., Willett, A. & Zijp, W. (1999). Agricultural extension: Generic challenges and some ingredients for solutions. World Bank. https://ssrn.com/abstract=620481

Fine, B. (1998). The political economy of diet, health and food policy. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203445297

Food and Agriculture Organization. (2001). Agricultural and rural extension worldwide: Options for the institutional reform in the developing countries. United Nations. http://www.fao.org/3/y2709e/y2709e.pdf

Food and Agriculture Organization. (2017, February 21). ICTs and agricultural extension services. E-Agriculture. United Nations. http://www.fao.org/e-agriculture/blog/icts-and-agricultural-extension-services

Gibson, N. P. (2013). Food justice and food security: Related NGOs & NPOs. University of Arkansas. https://uark.libguides.com/c.php?g=79244&p=508801

Jones, G. E., & Garforth, C. (1997). The history, development, and future of agricultural extension. In B. E. Swanson, R. P. Bentz, & A. J. Sofranko (Eds.), Improving agricultural extension: A reference manual (Chapter 1). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. http://www.fao.org/3/W5830E/w5830e03.htm

Mukembo, S. C., & Edwards, M. C. (2015). Agricultural extension in Sub-Saharan Africa during and after its colonial era: The case of Zimbabwe, Uganda, and Kenya. Journal of International Agricultural and Extension Education, 22(3), 50–68.

National Agricultural and Forestry Extension Service (NAFES). (2005). Consolidating extension in the Lao PDR. Lao People’s Democratic Republic. http://www.laolink.org/Literature/Consolidating_Extension_Laos.pdf

Pimber, M. P., Thompson, J., & Vorley, W. T. (2001). Global restructuring, agri-food systems and livelihoods. International Institute for Environment and Development. http://dlc.dlib.indiana.edu/dlc/bitstream/handle/10535/6125/Gatekeeper%20Series%20no100.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Purcell, D. L., & Anderson, J. R. (1997). Agricultural extension and research: Achievements and problems in national systems. World Bank.

Radhakrishna, R. (2020). AEE 525 Course Lecture Presentations. The Pennsylvania State University.

Rennekamp, R. A. (1995). A focus on the impacts: A guide for program planners. University of Kentucky Cooperative Extension Service.

United States Agency for International Development (USAID). (2015). Achieving gender equality in agriculture. https://www.usaid.gov/what-we-do/gender-equality-and-womens-empowerment/addressing-gender-programming/agriculture

Witkin, B. R., Altschuld, J. W., & Altschuld, J. (1995). Planning and conducting needs assessments: A practical guide. Sage.