14 Labor and Agriculture

Kaitlin Fischer

Learning Objectives

After reviewing this chapter, students will be able to:

- Discuss the various ways in which people’s farm labor supports food production in the United States and globally.

- Demonstrate how and why farm labor is crucial to understanding international agricultural development and inequities in the global food system.

- Examine the role of farmworkers in social movements in the United States and globally.

Introduction: What “Counts” as Farm Labor?

This chapter discusses agricultural labor with a focus on hired farmworkers. Unlike farmers, farmworkers do not own, lease, or manage the land upon which they are working and are not agricultural employers. In some contexts, however, the distinction between farmworker and farmer is not clear-cut. This is because farmers sometimes labor on other farmers’ farms in addition to their own (Gyapong, 2021; Teye et al., 2021). Women make significant contributions to agricultural production but are often not granted land ownership or other rights that would make their contributions more visible and acknowledged (Food and Agriculture Organization [FAO], 2011). In order to understand agricultural labor, we must consider not only what work is being done but also who is doing this work and where, when, how, and why they are doing it.

Agricultural Labor in the United States

Almost 50% of hired crop farmworkers in the United States are undocumented and only 25% were born in the United States, according to 2015–2016 data (Economic Research Service [ERS], 2020). Seventy-five percent are people of color (ERS, 2020). This statistic is reflective of the history of the U.S. agricultural workforce and directly connected to the lack of labor protections afforded farmworkers in legislation. When the U.S. Congress introduced labor legislation during the New Deal era of the 1930s, jobs primarily occupied by people of color, including farm work, were exempt (Asbed & Hitov, 2017; Rodman et al., 2016). In order to ensure passage of the legislation that today affords workers in most industries basic labor protections, Congress needed the votes of white congressmen representing Southern landholders who did not support paying minimum wage to their Black workers (Rodman et al., 2016). Although a few of these exemptions were removed in subsequent legislation (Rodman et al., 2016), many still exist today.

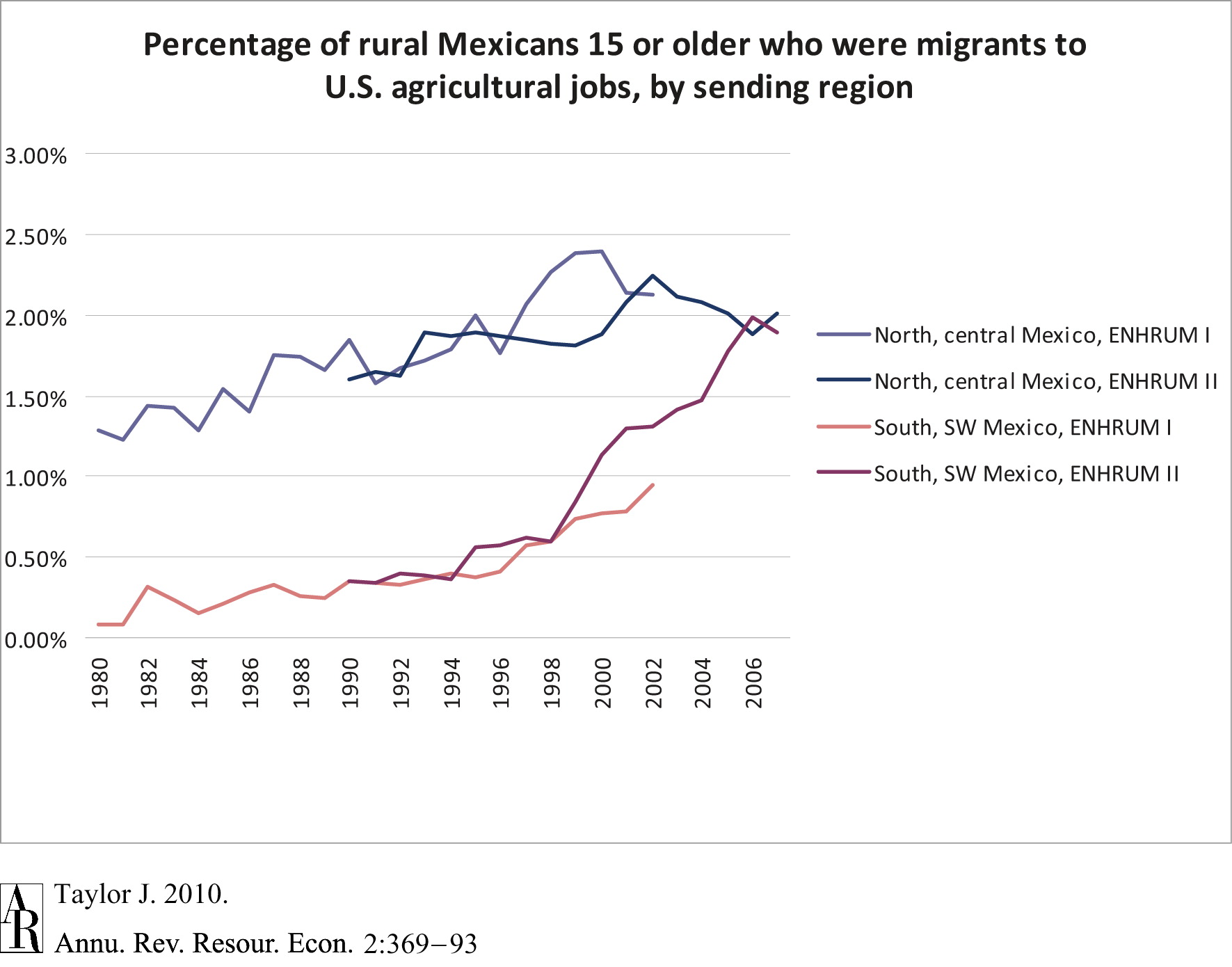

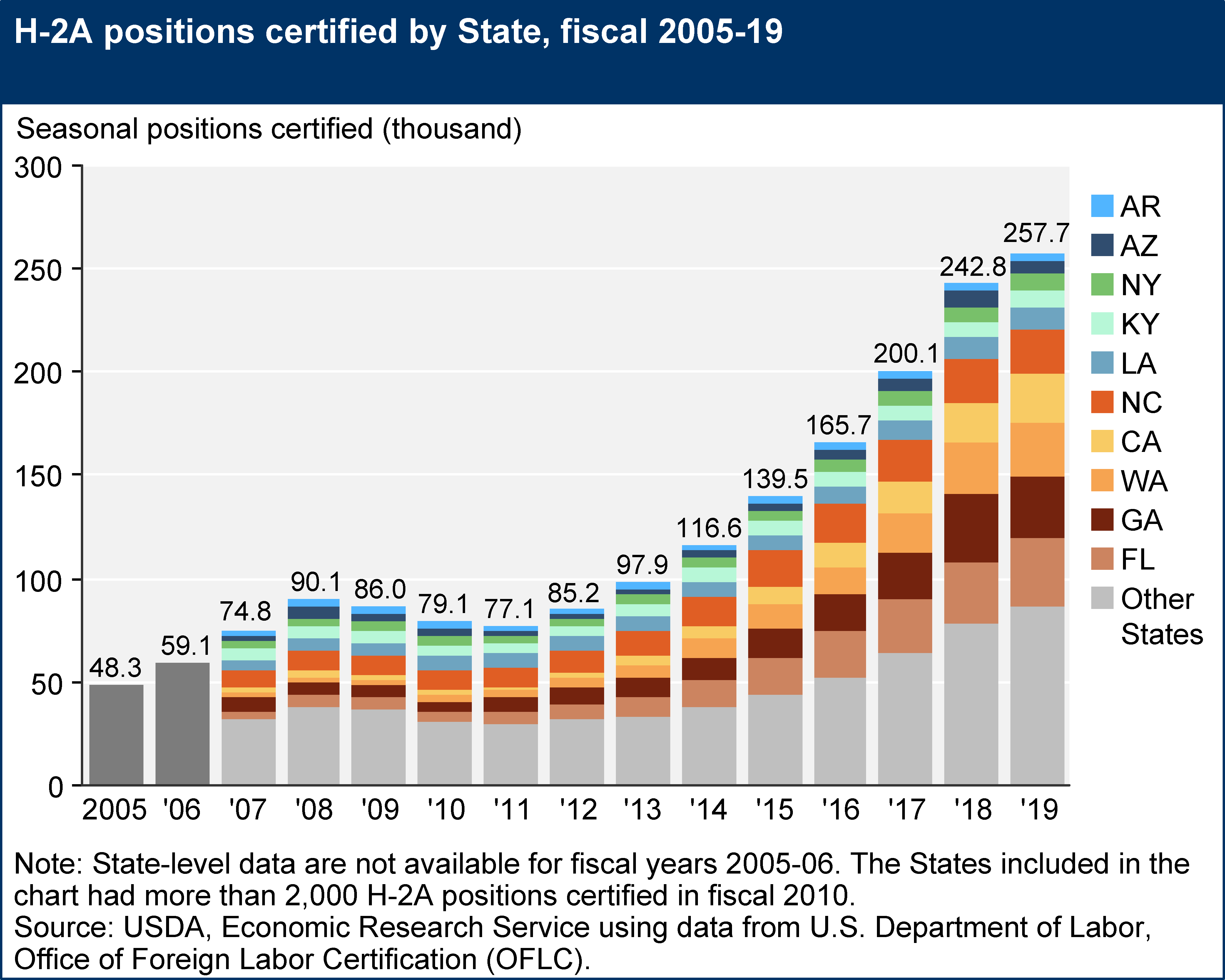

The employment of hired laborers on U.S. farms has long shown a reliance on workers of color, primarily foreign immigrant workers but at times domestic migrant workers as well (Taylor, 2010). Different immigrant groups have comprised the bulk of the U.S. farm workforce at various times in history in relationship with U.S. immigration policy. For instance, by the 1880s, 75% of California’s seasonal farmworkers were from China, but this changed with the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 (Taylor, 2010). Chinese laborers were replaced by immigrants from Japan, India and Pakistan, and Mexico; Dust Bowl migrants; and then Mexicans again (Martin, 2002). Over the course of 22 years (1942–1964) and multiple bracero programs (i.e., guest worker programs), about 4.6 million Mexicans came to the United States as temporary agricultural workers (Martin, 2002). What these successive immigration waves have in common is that landowning farm employers directly benefitted from decreased farm production costs and increased land prices that were the result of hiring seasonal, low-wage workers with very limited employment options (Martin, 2002). Mexicans still make up the majority of U.S. agricultural workers, with research indicating that the part of Mexico that workers tend to call home is shifting in part due to the employment conditions in their communities (Figure 1; Taylor, 2010). One mechanism through which workers legally enter the U.S. agricultural labor force is the H-2A Temporary Agricultural Program, or H-2A visa program for short (ERS, 2020). From 2005–2019, the number of temporary workers in this program increased fivefold (Figure 2; ERS, 2020).

Figure 1. “Shifting sources of Mexican farmworkers, 1980–2007. Calculated using data from Rounds I (2003) and II (2008) of the Mexico National Rural Household Survey [Encuesta Nacional a Hogares Rurales de México (ENHRUM)]” (Taylor, 2010, pp. C–8).

Figure 2. Rise of agricultural workers in H-2A Temporary Agricultural Program in U.S. states (ERS, 2020).

Today there are approximately 1.4 million crop farmworkers in the United States, yet their poor working conditions and limited rights are largely overlooked by the general population (Bon Appétit & United Farm Workers [UFW], 2011). According to the 2011 Inventory of Farmworker Issues and Protections, the main issues affecting U.S. farmworkers are:

- Lack of wage and hour standards: Labor laws at the federal and state levels often contain exemptions for farmworkers, meaning that many farmworkers are not entitled to the same wage and hour standards afforded to other workers. According to the Fair Labor Standards Act, small farms with seven or fewer full-time employees are not required to pay minimum wage. No farms are required to pay farmworkers overtime pay or offer rest or meal breaks. The fact that farmworkers are generally low-paid is compounded by their seasonal employment.

- Few labor protections for children and youth farmworkers: Between 300,000 and 800,000 youth work in agriculture in the United States. Like adult farmworkers, they lack the labor protections afforded to their counterparts in other sectors, such as restrictions on 16–18-year-olds performing hazardous tasks. When protections do exist at the state level, they are seldom enforced.

- Lack of transparency by farm labor contractors: Farm labor contractors serve as intermediaries between farmers and farmworkers since contractors set wages and working conditions. Farmers can thus argue they are not responsible for workers’ treatment and compensation. Farm labor contractors are required to comply with the Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act (AWPA) and to be certified by the U.S. Department of Labor, but many farm labor contractors are not registered and operate illegally.

- Substandard housing and unsafe transportation: These are both common according to legal advocates. Although protections exist in these areas under the AWPA, investigations into compliance are rare.

- Exclusion from unemployment insurance: According to the National Agricultural Workers Survey covering the period 2005–2009, only 48% of hired farmworkers and 23% of contract farmworkers report having access to unemployment insurance should they lose their job despite agricultural labor being seasonal in nature.

- Restrictions on collective bargaining: Very few farmworkers belong to a union. Under the federal National Labor Relations Act, agricultural workers do not have the right to do so or to engage in joint activities for their collective aid and protection.

- Forced labor abuses: Farmworkers comprise 10% of the forced labor (or “labor trafficking”) cases in the United States. Forced labor is when an individual is forced to work due to debts owed, confiscated passport or immigration documents, or threats of violence or deportation. Farmworkers are especially vulnerable when they have an exclusive contract with an employer connected to their legal right to work in the United States.

- Lack of workers’ compensation protections: Although farmworkers experience high rates of occupational injury and illness, making agriculture the country’s most hazardous industry according to the National Safety Council, only 55% of farmworkers surveyed between 2005 and 2009 had workers’ compensation insurance. This type of insurance helps pay for medical care and offset lost wages due to workplace injury or illness.

- Loopholes for Occupational Safety and Health Standards: The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has issued several safety and health standards specifically for agricultural workplaces, but it exempts farms from most general standards. Furthermore, one-third of all farmworkers in the United States are not protected by any OSHA standards since they work on small farms and farms with 11 employees or fewer are completely exempt.

- Heat stress: Farmworkers’ heat stress is underreported and often undiagnosed. While there are some exceptions at the state level, farm employers do not generally adequately protect employees from heat stress through the provision of shade and rest breaks.

- Pesticide exposure: Exposure to harmful pesticides is similarly undiagnosed and unreported, in part due to the OSHA loopholes previously mentioned (Bon Appétit & UFW, 2011).

While subject to the systemic inequities outlined above, individual farmworkers’ experience in U.S. agriculture is also influenced by their race, ethnicity, class, language, citizenship status, gender, and other aspects of their identity. These differences can sow division among agricultural workers, intentionally or inadvertently creating labor hierarchies that unevenly distribute power and vulnerability among the workers (Holmes, 2013). Employers may intentionally divide workers along lines of race for their own advantage. This is the case on some Hudson Valley, New York, farms, where undocumented Latino farmworkers have been hired instead of African Americans or Caribbeans who demanded higher wages (Gray, 2014). Because of their race and immigration status, Latino workers are viewed as more exploitable.

An increasing proportion of U.S. farmworkers are women; in 2018, this proportion stood at 25.5% (ERS, 2020). Sexsmith and Griffin (2020) find that sexual violence is built into the fabric of agricultural industries in the United States. Women farmworkers who experience sexual harassment on the job are often unable to leave said job due to a lack of other opportunities and their dependence on these low-paying positions to make ends meet (Sexsmith & Griffin, 2020). In this way, sexual violence reinforces labor exploitation at the same time that labor exploitation supports sexual violence. Undocumented women and men farmworkers also face increased vulnerability. For instance, California farmworkers as a population are at increased risk of food insecurity and hunger, but undocumented California farmworkers are at even higher risk since they are ineligible for public assistance programs that could help alleviate their food insecurity (Brown & Getz, 2011). In another example, among undocumented farmworkers on New York dairies, access to healthcare services via the government or marketplace is very limited (Sexsmith, 2017). These are some of the challenges facing farmworkers in the United States. The next section considers agricultural labor in an international context, beyond that of the U.S. farm.

Agricultural Labor Around the World

In the United States, as the percentage of the total population involved in agriculture has decreased, hired farmworkers have come to make up a greater proportion of the country’s agricultural workforce (ERS, 2020). Simultaneously, the proportion of workers on U.S. farms who are family members of self-employed farm operators has declined (ERS, 2020). This is a trend seen in many parts of the world where agriculture is becoming commercialized; that is, “the importance of hired labor tends to expand as commercial production displaces family production” (Taylor, 2010, p. 379). For this reason, it is crucial to understand how international agricultural development changes agricultural labor patterns, while also recognizing that the specific ways in which agricultural laborers are affected by agricultural development depend on local, regional, and national contexts.

Agriculture is unique from other economic sectors in several ways: agricultural production occurs across a wide range of scales, from small family farmers to large agribusinesses; it relies on biological processes and is seasonal; there are time lags between planting and harvesting; agriculture is geographically dispersed due to its land requirements; and it involves a high degree of risk in both production and marketing (Taylor, 2010). Some of these unique attributes, including the seasonality of farming and the inherent risks tied to natural processes, contribute to farmers’ desire for the flexible agricultural labor supply that migration helps to ensure (Taylor, 2010). In turn, farmers often engage in the political process to ensure a steady supply of seasonal migrants, who typically accept lower wages than domestic workers (Taylor, 2010). Taylor (2010) describes the situation facing farmers and farm workers across the globe:

Cross-country analysis of migration policies and anecdotal evidence on farm labor and immigration trends underline the universality of the farm labor problem. It is difficult to find farm labor migration policies or conditions in other countries that do not mirror aspects of the U.S. experience. Almost without exception, high-income countries depend heavily on immigrant agricultural workers. Many middle-income countries appear to be in the process of transitioning from a domestic to a foreign farm workforce, especially when they share a border with a poorer country. The range of international farm labor migration policies runs the gambit from tight government regulation of foreign recruitment and labor management, to not-so-benign neglect of unauthorized immigration, to regimes of limited enforcement punctuated by an occasional amnesty program. (p. 384)

Unfortunately, as our examination of farmworkers’ experiences have shown, while migration may solve a labor problem for farmers, it does not usually meet farmworkers’ need for a satisfactory living standard.

One way in which countries help control the national agricultural labor supply is through guestworker programs such as the H-2A program that is currently in use in the United States. It is estimated that by the year 2000, there were around 200 bilateral agreements negotiating labor supply between labor-exporting and labor-importing nations (Mannon et al., 2011). These guestworker programs are not only meant to fill agricultural labor shortages but also to encourage development in those countries sending migrant workers (Mannon et al., 2011). Weiler et al. (2020) find that both the H-2A program and its Canadian counterpart, the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program (SAWP), create precarious conditions for migrant workers—who are primarily from Mexico, followed by Jamaica—while accruing benefits mostly to large-scale agribusiness but also to some small-scale farms. These conditions include a very limited ability to change employers and low likelihood of obtaining legal permanent residence, both of which can contribute to farmworkers’ acceptance of challenging work conditions (Weiler et al., 2020).

Guestworker programs can also alleviate pressure on labor-exporting nations that are situated in a complex past and present involving “slavery, colonialism, trade liberalization, and structural adjustment programs, which often dispossessed migrant communities of their own farming livelihoods” (Weiler et al., 2020, p. 147). This suggests that farmworkers in one country may be farmers in another, or former farmers who have lost access to their land and/or their livelihood. For example, a Spanish guestworker program explicitly recruits mothers to work in southern Spain’s strawberry industry (Mannon et al., 2011). The presumed reason for recruiting mothers, principally from Morocco, is that doing so will satisfy the industry’s need for labor while lowering the likelihood that migrants will stay in Spain permanently. The program makes future employment dependent on migrant workers’ return to their home countries (Mannon et al., 2011).

In both the U.S. and international contexts, small-scale farms are not immune from hiring workers, including immigrant and migrant workers, or from engaging in labor exploitation (Gray, 2014; Tsikata, 2015). Because smallholder farms often rely on family labor, which changes as farms become more commercialized, further research is needed to more fully elucidate how agricultural development affects farmers’ use of family labor, hired labor, or some combination of the two (Tsikata, 2015). In their review of four books about agricultural workers published between 2013 and 2014, McLaughlin and Weiler (2017) draw attention to the strikingly similar structural constraints faced by agricultural workers who labor in the United States, Canada, Mexico, France, Spain, and Morocco. They note that “all of these countries undervalue, fail to properly support and even overtly discriminate against these needed workers. In all circumstances, labour protections and access to social services are inadequate, and workers are vulnerable to abuse, poor living and dangerous working conditions” (McLaughlin & Weiler, 2017, p. 635). These authors call for future research on the global connections characterizing the ubiquitous ill treatment of migrant farmworkers and their families.

Agricultural Labor in Ghana

This section spotlights two case studies in Ghana, West Africa. The case studies illustrate how different forms of agriculture intersect with sociocultural norms to shape labor relations as farms commercialize.

Case Study 1: NORPALM Company, a large-scale plantation

NORPALM is the fourth-largest oil palm producer in Ghana and as such is a significant source of employment. Agricultural workers do not receive permanent positions, however, and are often “field contract workers” hired by a third party—a field contractor. Field contractors pay workers’ wages out of the payment they receive from NORPALM but may not provide other benefits to workers. Other agricultural workers are hired as needed on a seasonal basis. Those who do receive permanent positions within the company are typically well-educated men, while less-educated men as well as women are employed in more casual positions.

Case Study 2: Somanya mango farms, medium-scale commercial farms

Mango farming is labor-intensive and thus also an important source of jobs. Here the type of position in which someone is employed depends on the scale of the farm. According to Teye et al. (2021), “Only wealthy mango farmers with farm sizes larger than five acres tend to employ permanent farm workers. Farmers with smaller farms prefer giving out contracts to labourers on [a] temporary basis, as this helps them to manage the cost of production” (p. 419). In other words, working on a larger farm may mean that workers have a more stable source of employment. But this is an opportunity available almost exclusively to men. Farmers prefer to hire women primarily for harvesting, temporary work for which they are deemed well-suited, rather than permanent work. Farmers’ wives may not approve of hiring women as permanent workers since these women are often perceived as having a relationship with the farmer. Finally, this commercial farming area employs many migrant workers. Put simply, “migrant labour has always been preferred because of the willingness of migrants to work under poorer conditions, their flexibility especially with regard to living on farms with limited freedoms, and their acceptance of comparatively lower wages compared to indigenes” (Teye et al., 2021, p. 422).

Case Study Complexity:

The aforementioned circumstances for farmworkers on the large-scale plantation and medium-scale commercial farm are by no means clear-cut or simple. Many casual farmworkers engage in other forms of off-farm work and/or supplement their low incomes by producing food for sustenance on their own farms. Some of these workers may identify as farmers and engage in casual work as necessary to sustain their own farm and household. Some workers may even prefer to be hired on a casual basis because although permanent employees have a guaranteed source of income, the income may be quite low. Family labor has not disappeared entirely but instead has taken on a hybrid form, such that in the areas in question, children are being paid by their households to perform agricultural labor. On the other hand, the women in these case studies are sometimes pushed into waged farm work on farms outside of their household or into farming on their own plots if the land is available. Mostly, however, they are pushed out of farming and into trading due to agricultural development.

Source: Teye et al. (2021).

Farmworker Movements

Unlike farmer movements, farmworker movements in the United States have objectives that align with those of the labor movement (Mooney & Majka, 1995). Their main objective is to obtain a better seat at the table “in negotiating more stable and productive employment arrangements” (Mooney & Majka, 1995, p. xviii). The current state of farmworkers’ employment arrangements, often predicated on farmworkers’ limited power and resources, has tended to limit their social movement success to short-term concessions rather than long-term structural change. For instance, low-income farmworkers typically do not have the ability to go on strike for a sustained period of time and may fear advocating for their rights, recognizing that doing so could compromise their immigration status and job. Various aspects of their work—such as its seasonality, the fact that laborers may not work on the same farm from one season to the next, and laborers’ migration across geographic areas—pose barriers to organizing in the first place. Nevertheless, farmworkers have found ways to achieve greater political power and accomplish their goals, including partnering with allies outside of agriculture (Mooney & Majka, 1995).

Minkoff-Zern (2017) argues that agricultural laborers and consumers can form alliances that are worker-centered and create meaningful change for workers. Accomplishing this requires not only consumers making changes in purchasing “but also applying their influence in boycotts, protests, and media campaigns” (Minkoff-Zern, 2017, p. 158). The largest food boycott in U.S. history was a boycott of grapes in the late 1960s, supporting worker strikes and marches led by the United Farm Workers (UFW) in response to low wages and miserable living and working conditions. UFW efforts, led by Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta, connected workers and consumers by drawing attention to shared health concerns over pesticide exposure and gained support and publicity from civil rights and antiwar groups. Grape growers eventually gave in to farmworkers’ demands for union contracts (and the higher wages and better conditions accompanying them) due in large part to the consumer boycotts that affected farmers’ profits (Minkoff-Zern, 2017). Although not union-based, in part because not all farmworkers have the right to unionize as California farmworkers do, the Coalition of Immokalee Workers is leading a contemporary Fair Food Program that engages consumers in farmworkers’ struggle for dignity in the fields.

Coalition of Immokalee Workers and Worker-Driven Social Responsibility

The Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW) is a human rights organization of farmworkers who work in Florida’s $650-million-dollar tomato industry (Asbed & Hitov, 2017). Their Fair Food Program has expanded beyond Florida to farms across the southeastern United States as far north as New Jersey and is in the process of expanding to Texas (Fair Food Program, n.d.a.). This program was initiated due to workers’ realization that in order to make changes in agriculture that would eliminate human rights abuses such as forced labor, workers needed to engage not only with farmers but also with the powerful corporate retailers who put pressure on farmers to reduce costs—typically at the expense of farmworkers (Asbed & Hitov, 2017; Fair Food Program, n.d.a.). Through the Fair Food Program, farmworkers, with the help of consumers whom they engage through initiatives like letter-writing, petitions, protests, and days of action at corporate headquarters, leverage retailers’ power to create change (Fair Food Program, n.d.a.; Minkoff-Zern, 2017). This happens when retailers agree to pay “a premium—a penny more [per] pound—for their produce, to be used as a wage supplement for farmworkers, and by agreeing to purchase only from growers who implemented a human rights-based Code of Conduct on their farms” (Fair Food Program, n.d.a., pp. 12–13). Through this model of “worker-driven social responsibility,” retailers sign legally binding agreements with workers’ organizations. This puts pressure on farmworkers’ employers since the retailers are the main buyers of their employers’ products.

The Fair Food Code of Conduct was created by and for farmworkers, who ask that they:

- Not be the victims of forced labor, child labor, or violence.

- Earn at least minimum wage.

- Always be paid for the work they do.

- Go to work without being sexually harassed or verbally abused.

- Be able to report mistreatment or unsafe working conditions.

- Report those abuses without the fear of losing their job—or worse.

- Have shade, clean drinking water, and bathrooms in the fields.

- Be allowed to use the bathroom and drink water while working.

- Be able to rest to prevent exhaustion and heat stroke.

- Be permitted to leave the fields when there is lightning, pesticide spraying, or other dangerous conditions.

- Be transported to work in safe vehicles. (Fair Food Program, n.d.a., p. 14)

These standards are guaranteed through worker-to-worker education, complaint resolution, auditing, and market-based enforcement (Fair Food Program, n.d.a., 2019). Fourteen major buyers currently participate, including Burger King, McDonald’s, Subway, and Walmart (Fair Food Program, n.d.b.).

Here are a few testimonials from farmworkers whose lives have been impacted by the CIW’s worker-driven social responsibility approach (Fair Food Program, 2019):

“Immokalee is a small town, but it is filled with hard-working and kind people—people who put food on the table for millions of other families. For many years when I worked in the fields, I did not always make enough to put food on my own table for my three children. Because of the Fair Food Program, we started to see better wages, and it changed our lives for the better—for me and for my children.” – Udelia (Farmworker), June 2018

“On the farms, there have been many changes. We have bathrooms, that’s one of the things we really needed. There is more respect on the farm, there are no more abuses. Before, the crewleaders and the fieldwalkers, they would say disgusting things to us and we just had to remain silent. But thanks to the Fair Food Program, we are ending these situations. These changes are now in many farms, but there are many more farms out there yet to be covered.” –Reina (Farmworker), June 2018

One CIW organizer, Gerardo Reyes, explains the importance of partnering with organizations such as the Student Farmworker Alliance:

The relationship with the organizations based here in Immokalee is very close. Together we develop plans we are considering implementing at a local and national level. For example, if we are planning a march, we ask ourselves, what does that mean for our network of allies? How can students and communities of different faiths engage? When is the most strategic time to hold an action to maximize its impact and ally participation? Which type of actions will have the strongest impact on corporate targets? These are examples of some of the questions we explore with our ally organizations. . . .

We work together with different organizations all over the country that support our campaign. Our intention is not just to harness support for our campaign, but to find ways to support the struggles and work of other communities. (as cited in Minkoff-Zern, 2017, p. 172)

As the CIW shows, “The power of farmworker grassroots organizing, combined with consumer power, has exhibited new ways that food injustice can be challenged by bridging physical and social geographical divisions. Recognizing workers as key actors in achieving social change opens new avenues for addressing inequalities in the food system” (Minkoff-Zern, 2017, p. 170).

For an overview of the CIW’s history and its present efforts advocating for farmworkers’ rights, check out this TedMed talk, “How Farmworkers Are Leading a 21st Century Human Rights Revolution”.

The largest social movement in the world is the movement for food sovereignty, or “community self-determination in producing and consuming food equitably and sustainably” (McMichael, 2017, p. 204). Yet while this movement has successfully advocated for peasant farmers’ right to produce their own food, often using low-input methods that are better for the planet (McMichael, 2017), it has been less successful at acknowledging differentiation among peasant farmers or between farmers and farmworkers—not to mention the fact that some people may be both farmers and workers (Bernstein, 2014; Gyapong, 2021). In other words, some scholars argue that the food sovereignty movement will ultimately be unsuccessful if it fails to recognize the differences between and among farmers and farmworkers. While counterintuitive on its surface, acknowledging these differences could actually lead to greater solidarity.

The Brazilian Landless Rural Workers Movement—in Portugese, the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (MST)—is an agrarian reform movement (Tarlau, 2015) that illustrates the ways in which farmworker and farmer movements can at times overlap. For almost 40 years, this movement has sought to redistribute agricultural land to landless Brazilians. Brazilians’ landlessness can be traced back to a 500-year history of land concentration initiated and facilitated by Portuguese colonizers (Tarlau, 2015). Brazil was also home to the largest and most recent slave trade in the Americas, and the descendants of the Black slaves who labored on plantations are today still mostly landless. The movement’s main strategy of occupying unused land has been very successful in securing land rights recognized by the Brazilian government for formerly landless rural workers. The movement has won land rights for 370,000 families, with about 900 land occupations currently underway by 150,000 still-landless Brazilian families (Friends of the MST, 2021). In tandem with these successes, however, “1,742 people have been killed due to agrarian conflicts, mostly peasant activists” (Tarlau, 2015, p. 3). Today, approximately 1% of the population owns 45% of the country’s land, while five million families remain without as landless rural workers (USAID, 2011).

Farmworkers and COVID-19

During the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic that began in 2020, farmworkers were deemed “essential workers” who must report to work as usual (Handal et al., 2020). This recognition of the critical necessity of farmworkers in producing the United States’ food supply has not, however, been accompanied by adequate measures to ensure their safety from contracting COVID-19 or real improvements to their living and working conditions (Asbed, 2020; Handal et al., 2020). Many of these conditions have increased the likelihood that workers will contract the virus. These conditions include shared, crowded housing with non-family members; transportation to and from the farm that similarly does not accommodate social distancing; poor sanitation; inadequate ventilation; and workplace power differentials that discourage workers from speaking out to ask for better protections against COVID-19 or from reporting illness or symptoms. As one of the founders of the CIW puts it, “The message to our country’s farmworkers is unmistakable: While your labor is essential, you are expendable. That is wrong, both morally and for our nation’s food security” (Asbed, 2020).

Conclusion

Farmworkers across the world are vulnerable to low wages, temporary employment, and in too many cases, poor working and living conditions. As farms develop and employ hired workers in greater numbers, the experiences of farmworkers in their individual contexts need to be studied. Farmworkers’ precarious conditions are often linked to legislation, international agreements, and other policies that tie immigrant and migrant workers to agricultural labor. Yet across the world, agricultural laborers have also been leaders fighting for change, showing that social movements driven by farmworkers themselves lead to outcomes that are not only better for workers but for employers, consumers, and communities as well. In order to succeed, these movements depend on the support of the public; to that end, please explore the “Related Organizations” and “Penn State Opportunities” sections below to find out how you can become involved.

Further Exploration

This is a timeline, with photos, of agricultural labor in the United States from Yaya and the National Farm Worker Ministry (n.d.).

This is a short video by CBS News about the state of agricultural labor in the United States and the CIW’s Fair Food Program that works to improve it (CBS Interactive Inc., 2015).

Related Organizations

Figure 3. A non-exhaustive list of farmworker-related organizations

For students at The Pennsylvania State University:

Two courses of possible interest:

- Community, Environment, and Development 497: Community-Engaged Learning with Pennsylvania Farmworkers is a two-credit course that “provides students with the opportunity to learn firsthand about immigration, local agriculture and labor issues through a language partnership with Spanish-speaking immigrant farmworkers on local dairy farms” (Penn State News, 2021).

- International Agriculture 300: Agricultural Production and Farming Systems in the Tropics is a three-credit course that delves into tropical food and farming systems. It includes a possible trip to a nonprofit organization in Florida working with migrant farmworkers to improve their food security and livelihoods.

Check out this Penn State News story for more information about these courses.

Check Your Knowledge

- What are the differences between farmers and farmworkers in terms of land access and employment relations? In what ways are the conditions of farmworkers in the United States similar to and different from the conditions of farmworkers outside of the United States?

- What is an agricultural guestworker program? What purpose does such a program serve for the farmers, farmworkers, sending countries, and receiving countries involved?

- What is the CIW and what are the main components of its Fair Food Program?

Synthesis Questions

- Explain a few ways in which agricultural development can alter labor relations on farms with different effects depending on one’s class, gender, race, ethnicity, citizenship, and/or age.

- Based on the differences between farmers and farmworkers (e.g., land access, employment relations), how would you expect farmers’ and farmworkers’ organizing efforts to differ? In other words, how might farmers’ versus farmworkers’ social movements differ in the United States? How might they differ abroad in low-income countries?

- Why has the Fair Food Program been so successful? What similarities and differences do you see between the CIW’s Fair Food Program and the UFW’s grape boycott of the 1960s?

References

Asbed, G. (2020, April 3). What happens if America’s 2.5 million farmworkers get sick? The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/03/opinion/coronavirus-farm-workers.html

Asbed, G., & Hitov, S. (2017). Preventing forced labor in corporate supply chains: The Fair Food Program and worker-driven social responsibility. Wake Forest Law Review, 52, 497–531.

Bernstein, H. (2014). Food sovereignty via the “peasant way”: A sceptical view. Journal of Peasant Studies, 41(6), 1031–1063. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2013.852082

Bon Appétit & United Farm Workers (UFW). (2011). Inventory of farmworker issues and protections in the United States. https://www.oxfamamerica.org/static/oa3/files/inventory-of-farmworker-issues-and-protections-in-the-usa.pdf

Brown, S., & Getz, C. (2011). Farmworker food insecurity and the production of hunger in California. In A. H. Alkon & J. Agyeman (Eds.), Cultivating food justice: Race, class, and sustainability (pp. 121–146). https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/8922.003.0010

CBS Interactive Inc. (2015). The growing demand for “fair food.” Retrieved May 1, 2021, from https://www.cbsnews.com/news/the-growing-demand-for-fair-food/

Economic Research Service (ERS). (2020). Farm labor. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://doi.org/10.2307/1230586

Fair Food Program. (n.d.a.). Fair Food: 2017 Annual Report. http://www.fairfoodprogram.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Fair-Food-Program-2017-Annual-Report-Web.pdf

Fair Food Program. (n.d.b.). Partners. Retrieved May 1, 2021, from https://www.fairfoodprogram.org/partners/

Fair Food Program. (2019). Fair Food: 2018 Update. https://www.fairfoodprogram.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Fair-Food-Program-2018-SOTP-Update-Final.pdf

Food and Agriculture Organization. (2011). The state of food and agriculture 2010–11: Women in agriculture, closing the gender gap for development. United Nations. https://doi.org/10.1109/PVSC.2008.4922754

Friends of the MST. (2021). What is the MST? Retrieved May 1, 2021, from https://www.mstbrazil.org/content/what-mst

Gray, M. (2014). Labor and the locavore: The making of a comprehensive food ethic. University of California Press.

Gyapong, A. Y. (2021). Land grabs, farmworkers, and rural livelihoods in West Africa: some silences in the food sovereignty discourse. Globalizations, 18(3), 339–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2020.1716922

Handal, A. J., Iglesias-Ríos, L., Fleming, P. J., Valentín-Cortés, M. A., & O’Neill, M. S. (2020). “Essential” but expendable: Farmworkers during the COVID-19 pandemic–The Michigan Farmworker Project. American Journal of Public Health, 110(12), 1760–1762. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305947

Holmes, S. M. (2013). Fresh fruit, broken bodies. University of California Press.

Mannon, S. E., Petrzelka, P., Glass, C. M., & Radel, C. (2011). Keeping them in their place: Migrant women workers in Spain’s strawberry industry. International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food, 19(1), 83–101.

Martin, P. (2002). Mexican workers and U.S. agriculture: The revolving door. International Migration Review, 36(4), 1124–1142.

McLaughlin, J., & Weiler, A. M. (2017). Migrant agricultural workers in local and global contexts: Toward a better life? Journal of Agrarian Change, 17(3), 630–638. https://doi.org/10.1111/joac.12199

McMichael, P. (2017). Development and social change: A global perspective (6th ed.). Russell Sage.

Minkoff-Zern, L.-A. (2017). Farmworker-led food movements then and now: United Farm Workers, the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, and the potential for farm labor justice. In A. H. Alkon & J. Guthman (Eds.), The new food Activism: Opposition, cooperation, and collective action (pp. 157–178). University of California Press.

Mooney, P. H., & Majka, T. J. (1995). Farmers’ and farm workers’ movements. Twayne Publishers.

Penn State News. (2021, March 29). College of Ag Sciences courses aim to broaden cultural understanding. The Pennsylvania State University. https://news.psu.edu/story/652887/2021/03/29/academics/college-ag-sciences-courses-aim-broaden-cultural-understanding

Rodman, S. O., Barry, C. L., Clayton, M. L., Frattaroli, S., Neff, R. A., & Rutkow, L. (2016). Agricultural exceptionalism at the state level: Characterization of wage and hour laws for U.S. farmworkers. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 6(2), 89–110. https://doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2016.062.013

Sexsmith, K. (2017). “But we can’t call 911”: Undocumented immigrant farmworkers and access to social protection in New York. Oxford Development Studies, 45(1), 96–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600818.2016.1193130

Sexsmith, K., & Griffin, M. A. M. (2020). Gender and precarious work in agriculture. In C. E. Sachs, L. Jense, P. Castellanos, & K. Sexsmith (Eds.), Routledge handbook of gender and agriculture (pp. 326–335). Routledge.

Tarlau, R. (2015). Brazilian Landless Rural Workers Movement (MST) sending a delegation to US. Turning the Tide, 28(1), 1–5.

Taylor, J. E. (2010). Agricultural labor and migration policy. Annual Review of Resource Economics, 2, 369–378. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-resource-040709-135048

Teye, J. K., Torvikey, G. D., & Yaro, J. A. (2021). Changing labour relations in commercial agrarian landscapes in Ghana. In P. Jha, W. Chambati, & L. Ossome (Eds.), Labour questions in the Global South (pp. 413–438). Springer Nature.

Tsikata, D. (2015). The social relations of agrarian change. In Food and agriculture. Retrieved from https://pubs.iied.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/migrate/17278IIED.pdf?

USAID. (2011). Brazil. Retrieved May 1, 2021, from LandLinks website: https://www.land-links.org/country-profile/brazil/#land

Yaya & National Farm Worker Ministry. (n.d.). Timeline of agricultural labor: Farm workers and immigration. https://pvarts.org/dev/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Yaya-Timeline-of-Agricultural-Labor-USA.pdf

Weiler, A. M., Sexsmith, K., & Minkoff-Zern, L.-A. (2020). Parallel precarity: A comparison of U.S. and Canadian agricultural guest worker programs. International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food, 26(2), 143–163.