1 Fitness Principles

By Scott Flynn

Objectives:

- Describe the origins of exercise

- Define physical activity and exercise

- Discuss principles of adaptation to stress

- Provide guidelines for creating a successful fitness program

- Identify safety concerns

Exercise: Not a Passing Fad

The benefits of physical activity and exercise are universally recognized—and have been for far longer than one might think. Our Paleolithic ancestors regularly engaged in physical activity to survive. However, rather than chasing after a soccer ball to win a game or taking a leisurely stroll down a tree-lined path, they “worked out” by chasing after their next meal. For them, no exercise meant no food. How’s that for a health benefit?

With the advent of sedentary agriculture some 10,000 years ago, that same level of peak performance was no longer necessary. As our ancestors continued to devise more advanced means of acquiring food, physical activity declined. It wasn’t until the fourth century BCE, that the Greek physician Herodicus, recognized the importance of being physically active outside of a hunter-gatherer society. He practiced gymnastic medicine, a branch of Greek medicine that relied on vigorous exercise as a treatment. During that same time period, Hippocrates, who is often referred to as the Father of Modern Medicine, asserted, “If we could give every individual the right amount of nourishment and exercise, not too little and not too much, we would have found the safest way to health.” In the 12 century CE, the Jewish philosopher Rabbi Moses ben Maimon, a physician to the Sultan of Egypt, stated, ”Anyone who lives a sedentary life and does not exercise, even if he eats good foods and takes care of himself according to proper medical principles, all his days will be painful ones and his strength will wane.” The 15th century theologian and scholar Robert Burton went so far as to declare that not exercising, or “idleness” as he referred to it in his widely read tome, The Anatomy of Melancholy, was the “bane of body and mind.” Burton also warned that the lack of exercise was the sole cause of melancholy (the name given depression at that time) and “many other maladies.” Burton claimed that idleness was one of the seven deadly, as well as “the nurse of naughtiness,” and the “chief author of mischief.” For Burton, exercise was not only essential for good health, but a means of avoiding eternal damnation.

By the 16th century, the benefits of exercise were widely accepted, at least among the wealthy and the educated, who had access to leisure. During this time period, H. Mercuralis defined exercise as “the deliberate and planned movement of the human frame, accompanied by breathlessness, and undertaken for the sake of health or fitness.” This definition is still widely used today.

Beyond the physical health benefits, there are affective benefits associated with group games and activities. Ancient Mayans organized the first team game called the Ball Game. It consisted of two teams trying to get a ball through a hoop mounted approximately 23 feet on a wall. The rules were to get the ball through the hoop using certain parts of the body. In some cases the captain of the losing team gave himself as a human sacrifice to the winning team, an act that was believed by the Mayans to be a vital part of prosperity.

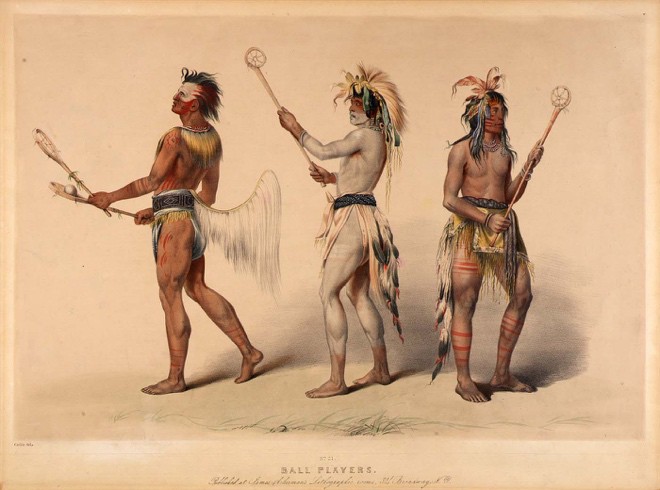

American Indians are thought to have founded the modern game of lacrosse, as well as other stick games. Lacrosse, which received its name from French settlers, was more than a form of recreation. It was a cultural event used to settle disputes between tribes.

Figure 1. Ball Players. George Catlin. Date unknown.

The outcome of the game, as well as the choosing of teams, was thought to be controlled supernaturally. As such, game venues and equipment were prepared ritualistically.

From Ancient History to Modern Times

In retrospect, the perceived benefits of exercise have changed very little since Herodicus or the American Indians. Mounting research supports historical assertions that exercise is vital to sustaining health and quality of life. Culturally, sports play a huge role in growth and development of youth and adults. Physically, there is indisputable evidence that regular exercise promotes healthy functioning of the brain, heart, and the skeletal and muscular systems. Exercise also reduces risk for chronic diseases, such as cancer, diabetes, and obesity. Regular exercise can even improve emotional health and overall well being.

What are Physical Activity and Exercise?

Physical activity is defined as any movement carried out by skeletal muscle that requires energy and is focused on building health. Health benefits include improved blood pressure, blood-lipid profile, and heart health. Acceptable physical activity includes yard work, house cleaning, walking the dog, or taking the stairs instead of the elevator. Physical activity does not have to be done all it once. It can be accumulated through various activities throughout the day. Although typing on a phone or laptop or playing video games does involve skeletal muscle and requires a minimal amount of energy, the amount required is not sufficient to improve health.

Despite the common knowledge that physical activity is tremendously beneficial to one’s health, rates of activity among Americans continue to be below what is needed. According to the Center for Disease Control (CDC), only 1 in 5 (21%) of American adults meet the recommended physical activity guidelines from the Surgeon General. Less than 3 in 10 high school students get 60 minutes or more of physical activity per day. Non-Hispanic whites (26%) are more active than their Hispanic (16%) and Black counterparts (18%) as is the case for males (54%) and females (46%). Those with more education and those whose household income is higher than poverty level are more likely to be physically active.1

The word exercise, although often used interchangeably with the phrase physical activity, denotes a sub-category of physical activity. Exercise is a planned, structured, and repetitive movement pattern intended to improve fitness. As a positive side-effect, it significantly improves health as well. Fitness improvements include the heart’s ability to pump blood, increased muscle size, and improved flexibility.

Components of Health-Related Fitness

In order to carry out daily activities without being physically overwhelmed, a minimal level of fitness is required. To perform daily activities without fatigue, it is necessary to maintain health in five areas: cardiorespiratory endurance, muscular strength and endurance, flexibility, and body composition. These five areas are called the components of health- related fitness. Development of these areas will improve your quality of life, reduce your risk of chronic disease, and optimize your health and well-being. Each of these 5 areas will be explored in depth at a later time. Below is a brief description of each.

- Cardiorespiratory endurance

Cardiorespiratory endurance is the ability to carry out prolonged, large muscle, dynamic movements at a moderate to high level of intensity. This relates to your heart’s ability to pump blood and your lungs’ ability to take in oxygen.

- Muscular strength

Muscular strength is the ability of the muscles to exert force over a single or maximal effort.

- Muscular endurance

Muscular endurance is the ability to exert a force over a period of time or repetitions.

- Flexibility

Flexibility is the ability to move your joints through a full range of motion.

- BodyComposition

Body composition is the relative amount of fat mass to fat-free mass. As previously stated, these areas are significant in that they influence your quality of life and overall health and wellness.

Skill-Related Components of Fitness

In addition to the 5 health-related components, there are 6 skill-related components that assist in developing optimal fitness: speed, agility, coordination, balance, power, and reaction time. Although important, these areas do not directly affect a person’s health. A person’s ability to perform ladder drills (also known as agility drills) is not related to his/her heart health. However, coordination of muscle movements may be helpful in developing muscular strength through resistance training. As such, they may indirectly affect the 5 areas associated with health-related fitness. Skill- related components are more often associated with sports performance and skill development.

Principles of Adaptation to Stress

The human body adapts well when exposed to stress. The term stress, within the context of exercise, is defined as an exertion above the normal, everyday functioning. The specific activities that result in stress vary for each individual and depend on a person’s level of fitness. For example, a secretary who sits at a desk all day may push his/her cardiorespiratory system to its limits simply by walking up several flights of stairs. For an avid runner, resistance training may expose the runner’s muscles to muscular contractions the athlete is not accustomed to feeling.

Although stress is relative to each individual, there are guiding principles in exercise that can help individuals manage how much stress they experience to avoid injury and optimize their body’s capacity to adapt. Knowing a little about these principles provides valuable insights needed for organizing an effective fitness plan.

Overload Principle

Consider the old saying, “No pain, no gain.” Does exercise really have to be painful, as this adage implies, to be beneficial?

Absolutely not. If that were true, exercise would be a lot less enjoyable. Perhaps a better way to relay the same message would be to say that improvements are driven by stress. Physical stress, such as walking at a brisk pace or jogging, places increased stress on the regulatory systems that manage increased heart rate and blood pressure, increased energy production, increased breathing, and even increased sweating for temperature regulation. As these subsequent adaptations occur, the stress previously experienced during the same activity, feels less stressful in future sessions. As a result of the adaptation, more stress must be applied to the system in order to stimulate improvements, a principle known as the overload principle.

For example, a beginning weightlifter performs squats with 10 repetitions at 150 pounds. After 2 weeks of lifting this weight, the lifter notices the 150 pounds feels easier during the lift and afterwards causes less fatigue. The lifter adds 20 pounds and continues with the newly established stress of 170 pounds. The lifter will continue to get stronger until his/her maximum capacity has been reached, or the stress stays the same, at which point the lifter’s strength will simply plateau. This same principle can be applied, not only to gain muscular strength, but also to gain flexibility, muscular endurance, and cardiorespiratory endurance.

FITT

In exercise, the amount of stress placed on the body can be controlled by four variables: Frequency, Intensity, Time (duration), and Type, better known as FITT. The FITT principle, as outlined by the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) falls under the larger principle of overload.

Frequency and Time

Each variable can be used independently or in combination with other variables to impose new stress and stimulate adaptation. Such is the case for frequency and time.

Frequency relates to how often exercises are performed over a period of time. In most cases, the number of walking or jogging sessions would be determined over the course of a week. A beginner may determine that 2–3 exercise sessions a week are sufficient enough to stimulate improvements. On the other hand, a seasoned veteran may find that 2–3 days is not enough to adequately stress the system. According to the overload principle, as fitness improves, so must the stress to ensure continued gains and to avoid plateauing.

The duration of exercise, or time, also contributes to the amount of stress experienced during a workout. Certainly, a 30-minute brisk walk is less stressful on the body than a 4-hour marathon.

Although independent of one another, frequency and time are often combined into the blanket term, volume. The idea is that volume more accurately reflects the amount of stress experienced. This can be connected to the progression principle. For example, when attempting to create a jogging plan, you may organize 2 weeks like this:

- Week 1: three days a week at 30 minutes per session

- Week 2: four days a week at 45 minutes per session

At first glance, this might appear to be a good progression of frequency and time. However, when calculated in terms of volume, the aggressive nature of the progression is revealed. In week 1, three days at 30 minutes per session equals 90 minutes of total exercise. In week two, this amount was doubled with four days at 45 minutes, equaling 180 minutes of total exercise. Doing too much, too soon, will almost certainly lead to burnout, severe fatigue, and injury. The progression principle relates to an optimal overload of the body by finding an amount that will drive adaptation without compromising safety.

Type of Exercise

Simply put, the type of exercise performed should reflect a person’s goals. In cardiorespiratory fitness, the objective of the exercise is to stimulate the cardiorespiratory system. Other activities that accomplish the same objective include swimming, biking, dancing, cross country skiing, aerobic classes, and much more. As such, these activities can be used to build lung capacity and improve cellular and heart function.

However, the more specific the exercise, the better. While vigorous ballroom dancing will certainly help develop the cardiorespiratory system, it will unlikely improve a person’s 10k time. To improve performance in a 10k, athletes spend the majority of their time training by running, as they will have to do in the actual 10k.

Cyclists training for the Tour de France, spend up to six hours a day in the saddle, peddling feverishly. These athletes know the importance of training the way they want their body to adapt. This concept, called the principle of specificity, should be taken into consideration when creating a training plan.

In this discussion of type and the principle of specificity, a few additional items should be considered. Stress, as it relates to exercise, is very specific. There are multiple types of stress. The three main stressors are metabolic stress, force stress, and environmental stress. Keep in mind, the body will adapt based on the type of stress being placed on it.

Metabolic stress results from exercise sessions when the energy systems of the body are taxed. For example, sprinting short distances requires near maximum intensity and requires energy (ATP) to be produced primarily through anaerobic pathways, that is, pathways not requiring oxygen to produce ATP. Anaerobic energy production can only be supported for a very limited time (10 seconds to 2 minutes). However, distance running at steady paces requires aerobic energy production, which can last for hours. As a result, the training strategy for the distance runner must be different than the training plan of a sprinter, so the energy systems will adequately adapt.

Likewise, force stress accounts for the amount of force required during an activity. In weightlifting, significant force production is required to lift heavy loads. The type of muscles being developed, fast-twitch muscle fibers, must be recruited to support the activity. In walking and jogging, the forces being absorbed come from the body weight combined with forward momentum. Slow twitch fibers, which are unable to generate as much force as the fast twitch fibers, are the type of muscle fibers primarily recruited in this activity. Because the force requirements differ, the training strategies must also vary to develop the right kind of musculature.

Environmental stress, such as exercising in the heat, places a tremendous amount of stress on the thermoregulatory systems. As an adaptation to the heat, the amount of sweating increases as does plasma volume, making it much easier to keep the body at a normal temperature during exercise. The only way to adapt is through heat exposure, which can take days to weeks to properly adapt.

In summary, to improve performance, being specific in your training, or training the way you want to adapt, is paramount.

Intensity

Intensity, the degree of difficulty at which the exercise is carried out, is the most important variable of FITT. More than any of the other components, intensity drives adaptation. Because of its importance, it is imperative for those beginning a fitness program to quantify intensity, as opposed to estimating it as hard, easy, or somewhere in between. Not only will this numeric value provide a better understanding of the effort level during the exercise session, but it will also help in designing sessions that accommodate individual goals.

How then can intensity be measured? Heart rate is one of the best ways to measure a person’s effort level for cardiorespiratory fitness. Using a percentage of maximum lifting capacity would be the measure used for resistance training.

Rest, Recovery, and Periodization

For hundreds of years, athletes have been challenged to balance their exercise efforts with performance improvements and adequate rest. The principle of rest and recovery (or principle of recuperation) suggests that rest and recovery from the stress of exercise must take place in proportionate amounts to avoid too much stress. One systematic approach to rest and recovery has led exercise scientists and athletes alike to divide the progressive fitness training phases into blocks, or periods. As a result, optimal rest and recovery can be achieved without overstressing the athlete. This training principle, called periodization, is especially important to serious athletes but can be applied to most exercise plans as well. The principle of periodization suggests that training plans incorporate phases of stress followed by phases of rest.

Training phases can be organized on a daily, weekly, monthly, and even multi-annual cycles, called micro-, meso-, and macrocycles, respectively. An example of this might be:

| Week | Frequency | Intensity | Time | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 Days | 40% HRR | 25 Min | Walk |

| 2 | 4 Days | 40% HRR | 30 Min | Walk |

| 3 | 4 Days | 50% HRR | 35 Min | Walk |

| 4 | 2 Days | 30% HRR | 30 Min | Other |

As this table shows, the volume and intensity changes from week 1 to week 3. But, in week 4, the volume and intensity drops significantly to accommodate a designated rest week. If the chart were continued, weeks 5-7 would be “stress” weeks and week 8 would be another rest week. This pattern could be followed for several months.

Without periodization, the stress from exercise would continue indefinitely eventually leading to fatigue, possible injury, and even a condition known as overtraining syndrome. Overtraining syndrome is not well understood. However, experts agree that a decline in performance resulting from psychological and physiological factors cannot be fixed by a few days’ rest. Instead, weeks, months, and sometimes even years are required to overcome the symptoms of overtraining syndrome. Symptoms include the following:

- weight loss

- loss of motivation

- inability to concentrate or focus

- feelings of depression

- lack of enjoyment in activities normally considered enjoyable

- sleep disturbances

- change in appetite

Reversibility

Chronic adaptations are not permanent. As the saying goes, “Use it or lose it.”

The principle of reversibility suggests that activity must continue at the same level to keep the same level of adaptation. As activity declines, called detraining, adaptations will recede.

In cardiorespiratory endurance, key areas, such as VO2max, stroke volume, and cardiac output all declined with detraining while submaximal heat rate increased. In one study, trained subjects were given bed rest for 20 days. At the end of the bed rest phase, VO2max had fallen by 27% and stroke volume and cardiac output had fallen by 25%. The most well-trained subjects in the study had to train for nearly 40 days following bed rest to get back into pre-rest condition. In a study of collegiate swimmers, lactic acid in the blood after a 2- minute swim more than doubled after 4 weeks of detraining, showing the ability to buffer lactic acid was dramatically affected.2

Not only is endurance training affected, but muscular strength, muscular endurance, and flexibility all show similar results after a period of detraining.

Individual Differences

While the principles of adaptation to stress can be applied to everyone, not everyone responds to stress in the same way. In the HERITAGE Family study, families of 5 (father, mother, and 3 children) participated in a training program for 20 weeks. They exercised 3 times per week, at 75% of their VO2max, increasing their time to 50 minutes by the end of week 14. By the end of the study, a wide variation in responses to the same exercise regimen was seen by individuals and families. Those who saw the most improvements saw similar percentage improvements across the family and vice versa. Along with other studies, this has led researchers to believe individual differences in exercise response are genetic. Some experts estimate genes to contribute as much as 47% to the outcome of training.

In addition to genes, other factors can affect the degree of adaptation, such as a person’s age, gender, and training status at the start of a program. As one might expect, rapid improvement is experienced by those with a background that includes less training, whereas those who are well trained improve at a slower rate.

Fitness Guidelines

The recommendations linked above pertain to physical activity only. While they can be applied to fitness, more specific guidelines have been set to develop fitness. As stated previously, physical activity is aimed at improving health; exercise is aimed at improving health and fitness. These guidelines will be referenced often as each health-related component of fitness is discussed.

Creating a Successful Fitness Plan

Often, the hardest step in beginning a new routine is simply starting the new routine. Old habits, insufficient motivation, lack of support, and time constraints all represent common challenges when attempting to begin a new exercise program. Success, in this case, is measured by a person’s ability to consistently participate in a fitness program and reap the fitness benefits associated with a long-term commitment.

Think Lifestyle

Beginning a fitness program is a daunting task. To illustrate the concept of lifestyle, consider attendance at fitness centers during the month of January. Attendance increases dramatically, driven by the number 1 New Year’s resolution in America: losing weight. Unfortunately, as time marches on, most of these new converts do not. By some estimates, as many as 80% have stopped coming by the second week in February. As February and March approach, attendance continues to decline, eventually falling back to pre-January levels.

Why does this occur? Why aren’t these new customers able to persist and achieve their goal of a healthier, leaner body? One possible explanation: patrons fail to view their fitness program as a lifestyle. The beginning of a new year inspires people to make resolutions, set goals, as they envision a new and improved version of themselves. Unfortunately, most of them expect this transformation to occur in a short period of time. When this does not happen, they become discouraged and give up.

Returning to teen level weight and/or fitness may be an alluring, well-intended goal, but one that is simply unrealistic for most adults. The physical demands and time constraints of adulthood must be taken into consideration for any fitness program to be successful. Otherwise, any new fitness program will soon be abandoned and dreams of physical perfection fade, at least until next January.

Like any other lifestyle habit, optimal health and fitness do not occur overnight. Time and, more importantly, consistency, drive successful health and fitness outcomes. The very term lifestyle refers to changes that are long term and become incorporated into a person’s daily routine. Unlike many fad diets and quick fixes advertised on television, successful lifestyle changes are also balanced and reasonable. They do not leave you feeling depressed and deprived after a few days. Find a balance between what you want to achieve and what you are realistically able to do. Finally, you must do more than simply change your behaviors. You must also modify your mental perception to promote long-term health. Find a compelling reason for incorporating healthier behaviors into your daily routine.

The steps below will guide you through this process. Before beginning a fitness program, you should understand the safety concerns associated with exercise.

Safety First: Assessing Your Risk

The physical challenges of beginning a new exercise program increase the risk of injury, illness, or even death. Results from various studies suggest vigorous activity increases the risk of acute cardiac heart attacks and/or sudden cardiac death.3 While that cautionary information appears contradictory to the previously identified benefits of exercise, the long-term benefits of exercise unequivocally outweigh its risks. In active young adults (younger than 35), incidence of cardiac events are still rare, affecting 1 in 133,000 in men and 1 in 769,000 in women. In older individuals, 1 in 18,000 experience a cardiac event. 4

Of those rare cardiac incidents that do occur, the presence of preexisting heart disease is the common thread, specifically, atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis causes arteries to harden and become clogged with plaque, which can break apart, move to other parts of the body, and clog smaller blood vessels. As such, it is important to screen individuals for risk factors associated with heart disease before they begin an exercise program.

The American College of Sports Medicine recommends a thorough pre-screening to identify any risk of heart disease. The 7 major risk factors associated with increased risk of heart disease are identified below.5

- Family history

Having a father or first-degree male relative who has experienced a cardiac event before the age of 55, or a mother or first-degree female relative who has experienced a cardiac event before age 65, could indicate a genetic predisposition to heart disease.

- Cigarette smoking

The risk of heart disease is increased for those who smoke or have quit in the past 6 months.

- Hypertension

Having blood pressure at or above 140 mm/HG systolic, 90 mm/Hg diastolic is associated with increased risk of heart disease.

- Dyslipidemia

Having cholesterol levels that exceed recommendations (130 mg/dL, HDL below 40 mg/dL), or total cholesterol of greater than 200 mg/dL increases risk.

- Impaired fasting glucose (diabetes)

Blood sugar should be within the recommended ranges.

- Obesity

Body mass index greater than 30, waist circumference of larger than 102 cm for men and larger than 88 cm for women, or waist to hip ratio of less than 0.95 men, or less than 0.86 women increases risk of heart disease.

- Sedentary lifestyle

Persons not meeting physical activity guidelines set by US Surgeon General’s Report have an increased risk of heart disease.

In addition to identifying your risk factors, you should also complete a Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q) before beginning an exercise program. The PAR-Q asks yes or no questions about symptoms associated with heart disease. Based on your responses on the PAR-Q, you will be placed into a risk category: low, moderate, high.

- Low risk persons include men younger than 45, and women younger than 55, who answer no to all of the PAR-Q questions and have one or no risk factors. Although further screening is a good idea, such as getting physician’s approval, it isn’t necessary.

- Moderate risk persons are men of or greater than 45, women 55 or those who have two or more risk factors. Because of the connection between cardiac disease, the seven risk factors, and risk during exercise, it is recommended you get a physician’s approval before beginning an exercise program.

- High risk persons answer yes to one or more of the questions on the PAR-Q. Physician’s approval is required before beginning a program.

Once you have determined your ability to safely exercise, you are ready to take the next steps in beginning your program.

Additional safety concerns, such as where you walk and jog, how to be safe during your workout, and environmental conditions, will be addressed at a later time.

As you review the remaining steps, a simple analogy may help to better conceptualize the process.

Imagine you are looking at a map because you are traveling to a particular location and you would like to determine the best route for your journey. To get there, you must first determine your current location and then find the roads that will take you to your desired location. You must also consider roads that will present the least amount of resistance, provide a reasonably direct route, and do not contain any safety hazards along the way. Of course, planning the trip, while extremely important, is only the first step. To arrive at your destination, you must actually drive the route, monitoring your car for fuel and/or malfunction, and be prepared to reroute should obstacles arise.

Preparing yourself for an exercise program and ultimately, adopting a healthier lifestyle, requires similar preparation. You will need to complete the following steps:

- Assess your current fitness

Where are you on the map?

- Set goals

What is your destination’s location?

- Create a plan

What route will you choose?

- Follow through

Start driving!

Assess Your Condition

To adequately prepare, you will need to take a hard look at your current level of fitness. With multiple methods of assessing your fitness, you should select the one that most closely applies to you. Obtaining a good estimate will provide you a one-time glance at your baseline fitness and health and provide a baseline measurement for gauging the efficacy of your fitness program in subsequent reassessments.

Assessments are specific to each health- related component of fitness. You will have the opportunity to assess each one in the near future.

Set Goals

Using the map analogy, now that you know your current location, you must determine your destination and the best route for getting there. You can start by setting goals. In his bestselling book, The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, author Stephen Covey suggests you should “Begin with the end in mind.”7 While Covey’s words may not be directly aimed at those seeking to complete a fitness program, his advice is useful to anyone making a significant lifestyle change. To be successful, you must develop a clear vision of your destination.

Setting specific goals about how you want to feel and look, increases your chances of success. Without specific goals to measure the success of your efforts, you could possibly exceed your target and believe you failed.

The art of setting goals includes stating them in a clearly defined and measurable way. Consider exactly what you would like to accomplish, make certain your goals can be measured, and establish a reasonable timeframe in which to achieve your goals.

Goals that meet these guidelines are referred to as S.M.A.R.T. goals.

- Specific

Be as specific and detailed as possible in creating your goal.

- Measurable

If your goal cannot be measured, you will not know when you have successfully completed the goal.

- Attainable

Consider whether you have the resources—such as time, family support, and financial means—to obtain your goal.

- Realistic

While your goal should be challenging, it should not exceed reasonable expectations.

- Timeframe

Set a deadline to accomplish your goal.

A well-stated goal contains all of the SMART components listed above. Take a look at the well-stated example below:

I will improve my 12-minute distance by 10% within 2 months of the first assessment.

Note, all the ingredients of a well-stated goal are present. It is specific (improve 12- minute distance by 10%), measurable (10% improvement), attainable and realistic (the degree of improvement is reasonable in that time frame), and includes a time frame (a clear deadline of 2 months).

Less effective goals would be stated like this:

- I will run farther next time I assess my fitness.

- I want to jog faster.

- I will lose weight

And a common one:

- I will exercise 3 days a week at 60% max heart rate for 45 minutes per session for 2 months.

At a closer glance, none of these examples contain all of the ingredients of a well- stated goal. How can “faster” be measured? “Farther” is not specific enough, nor is “lose weight.” In the last example, this is not a goal at all. It is a plan to achieve a goal that has not been stated.

In the end, setting up well-stated goals will give you the best chance to convert good intentions into a healthier lifestyle.

To complete this step, write down 2-3 personal goals, stated in the SMART format, and put them in a place you will see them frequently.

Create a Plan

Once you know exactly what you want to achieve, generate a strategy that will help you reach your goals. As you strategize, your goal is to determine the frequency, the intensity, and the duration of your exercise sessions. While doing this, it is imperative to keep in mind a few key principles.

First, use your goals as the foundation for your program. If your goal is related to weight loss, this should drive the frequency, duration, and intensity of your daily workouts as these variables will influence your body’s use of fat for fuel and the number of calories burned. If you feel more interested in improving your speed, you will need to dedicate more workout time to achieving those results.

Another key principle is the importance of safety. The importance of designing a program that is safe and effective cannot be overstated. You can minimize any risks by relying on the expert recommendations of the US Department of Health and Human Services and the American College of Sports Medicine previously outlined and linked here. These highly reputable organizations have conducted extensive research to discover the optimal frequency, intensity, and duration for exercise.

Follow Through

Once you have assessed your current fitness levels, set goals using the SMART guidelines, and created your personalized fitness plan, you should feel very proud of yourself! You have made significant progress toward achieving a healthier lifestyle. Now is when the “rubber hits the road.” (Literally so, if your plan includes walking or jogging.) Now that you have invested time and energy to develop a thoughtful, well-designed fitness program, it is time to reap the returns of good execution. The assessment, planning and preparation are really the hardest parts.

Once you know what to do and how to do it, success is simply a matter of doing it.

Unfortunately, the ability to stick with a program proves difficult for most. To prevent getting derailed from your program, identify barriers that may prevent you from consistently following through.

One of the most common challenges cited is a shortage of time. Work schedules, school, child care, and the activities of daily living can leave you with little time to pursue your goals. Make a list of the items that prevent you from regularly exercising and then analyze your schedule and find a time for squeezing in your exercise routine. Regardless of when you schedule your exercise, be certain to exercise consistently. Below are a few additional tips for achieving consistency in your daily fitness program:

- Think long term; think lifestyle.

The goal is to make exercise an activity you enjoy every day throughout your life. Cultivating a love for exercise will not occur overnight and developing your ideal routine will take time. Begin with this knowledge in mind and be patient as you work through the challenges of making exercise a consistent part of your life.

- Start out slowly.

Again, you are in this for the long haul. No need to overdo it in the first week. Plan for low intensity activity, for 2–3 days per week, and for realistic periods of time (20–30 minutes per session).

- Begin with low Intensity/low volume.

As fitness improves, you will want to gradually increase your efforts in terms of quantity and quality. You can do this with more time and frequency (called volume) or you can increase your intensity. In beginning a program, do not change both at the same time.

- Keep track.

Results from a program often occur slowly, subtly, and in a very anti- climactic way. As a result, participants become discouraged when immediate improvements are not visible. Keeping track of your consistent efforts, body composition, and fitness test results and seeing those subtle improvements will encourage and motivate you to continue.

- Seek support.

Look for friends, family members, clubs, or even virtual support using apps and other online forums. Support is imperative as it provides motivation, accountability, encouragement, and people who share a common interest, all of which are factors in your ability to persist in your fitness program.

- Vary your activities from time to time.

Your overall goals are to be consistent, build your fitness, and reap the health benefits associated with your fitness program. Varying your activities occasionally will prevent boredom. Instead of walking, play basketball or ride a bike. Vary the location of your workout by discovering new hiking trails, parks or walking paths.

- Have fun.

If you enjoy your activities, you are far more likely to achieve a lasting lifestyle change. While you cannot expect to be exhilarated about exercising every day, you should not dread your daily exercise regimen. If you do, consider varying your activities more, or finding a new routine you find more enjoyable.

- Eat healthier.

Nothing can be more frustrating than being consistent in your efforts without seeing the results on the scale. Eating a balanced diet will accelerate your results and allow you to feel more successful throughout your activities.

Additional Safety Concerns

As activity rates among Americans increase, specifically outdoor activities, safety concerns also rise. Unfortunately, the physical infrastructure of many American cities does not accommodate active lifestyles. Limited financial resources and de-emphasis on public health means local and state governments are unlikely to allocate funds for building roads with sidewalks, creating walking trails that surround parks, or adding bike lanes. In addition, time constraints and inconvenience make it challenging for participants to travel to areas where these amenities are available. As a result, exercise participants share roads and use isolated trails/pathways, inherently increasing the safety risks of being active.

A key principle in outdoor safety is to recognize and avoid the extremes. For example, avoid roads that experience heavy traffic or are extremely isolated. Avoid heavy populated areas as well as places where no one is around. Do not exercise in the early morning or late at night, during extreme cold or extreme heat. To minimize safety risks during these types of environmental conditions, do not use headphones that could prevent you from hearing well and remaining alert, do not exercise alone, prepare for adequate hydration in the heat, and use warm clothing in extreme cold to avoid frostbite. Extreme conditions require extra vigilance on your part.

A second key principle, whether outdoor or indoor, is to simply use common sense.

While this caveat seems obvious, it gets ignored far too often. Always remember the purpose of your exercise is for enjoyment and improved health. If these objectives could be compromised by going for a run at noon in 95-degree heat, or lifting large amounts of weight without a spotter, you should reconsider your plan. Before exercising in what could be risky conditions, ask yourself, “Is there a safer option available?”

Lastly, be aware of the terrain and weather conditions. Walking or jogging on trails is a wonderful way to enjoy nature, but exposed roots and rocks present a hazard for staying upright. Wet, muddy, or icy conditions are additional variables to avoid in order to complete your exercise session without an accident.

The document linked below from the University of Texas at San Antonio Police Department outlines specific safety tips that will help you stay safe in your activities.

Safety Tips for Runners, Walkers, and Joggers

Environmental Conditions

When exercising outdoors, you must consider the elements and other factors that could place you at increased risk of injury or illness.

Heat-Related Illness

Heat-related illnesses, such as heat cramps, heat exhaustion, and heat stroke, contributed to 7,233 deaths in the United States between 1999 and 2009. A 2013 report released by the Center for Disease Control stated that about 658 deaths from heat-related illnesses occurred every year which account for more deaths than tornadoes, hurricanes, and lightning combined. Of those deaths, most were male, older adults.8

The number one risk factor associated with heat-related illness is hydration, the starting point of all heat-related illness.

Unfortunately, sweat loss can occur at a faster rate than a person can replace with fluids during exercise, especially at high intensities. Even when trying to hydrate, ingestion of large amounts of fluids during exercise can lead to stomach discomfort. What does this mean? Hydration must begin before exercise and must become part of your daily routine.

Several practical methods of monitoring hydration levels can assist in preventing illness. One simple method, while not full proof, is to simply monitor the color of your urine. In a hydrated state, urination will occur frequently (every 2–3 hours) and urine will have very little color. In a dehydrated state, urination occurs infrequently in low volume and will become more yellow in color.

Another simple method involves weighing yourself before and after a workout (see lab). This is a great way to see firsthand how much water weight is lost during an exercise session primarily as a result of sweat. Your goal is to maintain your pre- and post-body weight by drinking fluids during and after the workout to restore what was lost. This method, when combined with urine-monitoring, can provide a fairly accurate assessment of hydration levels.

The best preventative measure for maintaining a hydrated state is simply drinking plenty of water throughout the day. In previous years, recommendations for the amount of water to drink were a one size fits all of about 48–64 oz. per day, per person. In an effort to individualize hydration, experts now recommend basing fluid intake on individual size, gender, activity levels, and climate. Generally, half an ounce (fluid ounces) to 1 ounce per pound of body weight is recommended.9 For a 150-pound individual, this would mean 75–150 ounces of water per day!

While there is still considerable debate over the exact amounts, no one disputes the importance of continually monitoring your hydration using one of the techniques described previously. Insufficient hydration leads to poor performance, poor health, and potentially serious illness.

It should be noted that electrolyte “sport” drinks, such as Gatorade and PowerAde, are often used to maintain hydration. While they can be effective, these types of drinks were designed to replace electrolytes (potassium, sodium, chloride) that are lost through sweating during physical activity. In addition, they contain carbohydrates to assist in maintaining energy during activities of long duration. If the activity planned is shorter than 60 minutes in duration, water is still the recommended fluid. For activities beyond 60 minutes, a sports drink should be used.

Cold-Related Illnesses

Much like extremely hot environmental conditions, cold weather can create conditions equally as dangerous if you fail to take proper precautions. To minimize the risk of cold-related illness, you must prevent the loss of too much body heat.

The three major concerns related to cold- related illnesses are hypothermia, frost-nip, and frost bite.

As with heat-related illness, the objective of preventing cold-related illness is to maintain the proper body temperature of between 98.6 and 99.9 degrees Fahrenheit. If body temperature falls below 98.6 F, multiple symptoms may appear, indicating the need to take action. Some of those symptoms include:

- shivering

- numbness and stiffness of joints and appendages

- loss of dexterity and/or poor coordination

- peeling or blistering of skin, especially to exposed areas

- discoloration of the skin in the extremities

When walking or jogging in the cold, it is important to take the necessary steps to avoid problems that can arise from the environmental conditions.

- Hydration is key.

Cold air is usually drier air, which leads to moisture loss through breathing and evaporation. Staying hydrated is key in maintaining blood flow and regulating temperature.

- Stay dry.

Heat loss occurs 25x faster in water than on dry land. As such, keeping shoes and socks dry and clothing from accumulating too much sweat will allow for more effective body temperature regulation.

- Dress appropriately.

Because of the movement involved, the body will produce heat during the exercise session. Therefore, the key point is to direct moisture (sweat) away from the skin. This is controlled most effectively by layering your clothing. A base layer of moisture-wicking fabric should be used against the skin while additional layers should be breathable. This will channel moisture away from the skin, and any additional layers of clothing, without it becoming saturated in sweat. If exercising on a windy day, use clothing that protects from the wind and is adjustable so you can breathe.

- Cover the extremities.

Those parts of the body farthest away from the heart (toes, fingers, and ears) tend to get coldest first. Take the appropriate steps to cover those areas by using gloves, moisture-wicking socks, and a winter cap to cover your head.

References:

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Retrieved April 2017, CDC: Physical Activity, Data and Statistics, https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/data/facts.htm

- Saltin, B., Blomqvist, G., Mitchell, J.H., Johnson, R.L., Jr., Wildenthal, K., Chapman, C.B. Response to submaximal and maximal exercise after bed rest and training. 1968 Nov, Vol. 38 (Suppl. 5)

- Noakes, Timothy D.; Sudden Death and Exercise, Sportscience, 1998, retrieved Dec. 2017, http://www.sportsci.org/jour/9804/tdn.html

- Van Camp SP, Boor CM, Mueller FO, et al. Non-traumatic Sports Death in High School and college Athletes, Medicine and Science of Sports and Exercise 1995; 27:641-647

- American College of Sports Medicine, 7th Edition, ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription, Philadelphia, PA, Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, p. 10

- American College of Sports Medicine, 7th Edition, ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription, Philadelphia, PA, Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, p. 27

- 7 Habits of Highly Effective People,2003, Covey, Stephen R. Habit 2, New York, Franklin Covey Co. p. 40-61

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Retrieved April 2017, CDC: Quick Stats: Number of Heat-related Deaths, by Sex-National Vital Statistics System-United States, 1999-2010, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6136a6.htm

- Mayo Clinic, retrieved April 2017, Water: How Much Should You Drink Each Day? http://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/nutrition-and-healthy-eating/in- depth/water/art-20044256